| Revision as of 20:13, 11 April 2024 view sourceCoolieCoolster (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users49,705 edits Removed extra space (via WP:JWB)Tag: Reverted← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:13, 11 April 2024 view source CoolieCoolster (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users49,705 edits Removed extra space (via WP:JWB)Tags: Reverted harv-errorNext edit → | ||

| Line 175: | Line 175: | ||

| ], {{Circa|October 7, 1960}}.]] | ], {{Circa|October 7, 1960}}.]] | ||

| The Kennedy and Nixon campaigns agreed to a series of ].<ref name="auto2">{{cite web |title=Campaign of 1960 |url=https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/campaign-of-1960 |website=John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum |access-date=October 15, 2023 |archive-date=October 17, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231017205150/https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/campaign-of-1960 |url-status=live }}</ref> An estimated 70 million Americans, about two-thirds of the electorate, watched the first debate on September 26.<ref name="museum.tv">{{cite web |url=http://www.museum.tv/eotvsection.php?entrycode=kennedy-nixon |title=THE KENNEDY-NIXON PRESIDENTIAL DEBATES, 1960 – The Museum of Broadcast Communications |publisher=] (MBC) |access-date=October 8, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100821064309/http://www.museum.tv/eotvsection.php?entrycode=kennedy-nixon |archive-date=August 21, 2010 |url-status=dead }}</ref> Kennedy had met the day before with the producer to discuss the set design and camera placement. Nixon, just out of the hospital after a painful knee injury, did not take advantage of this opportunity and during the debate looked at the reporters asking questions and not at the camera. Kennedy wore a blue suit and shirt to cut down on glare and appeared sharply focused against the gray studio background. Nixon wore a light-colored suit that blended into the gray background; in combination with the harsh studio lighting that left Nixon perspiring, he offered a less-than-commanding presence. By contrast, Kennedy appeared relaxed, tanned, and telegenic, looking into the camera whilst answering questions.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Selverstone |first1=Marc J. |title=The Campaign and Election of 1960 |url=https://millercenter.org/president/kennedy/campaigns-and-elections |website=University of Virginia: Miller Center | |

The Kennedy and Nixon campaigns agreed to a series of ].<ref name="auto2">{{cite web |title=Campaign of 1960 |url=https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/campaign-of-1960 |website=John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum |access-date=October 15, 2023 |archive-date=October 17, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231017205150/https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/campaign-of-1960 |url-status=live }}</ref> An estimated 70 million Americans, about two-thirds of the electorate, watched the first debate on September 26.<ref name="museum.tv">{{cite web |url=http://www.museum.tv/eotvsection.php?entrycode=kennedy-nixon |title=THE KENNEDY-NIXON PRESIDENTIAL DEBATES, 1960 – The Museum of Broadcast Communications |publisher=] (MBC) |access-date=October 8, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100821064309/http://www.museum.tv/eotvsection.php?entrycode=kennedy-nixon |archive-date=August 21, 2010 |url-status=dead }}</ref> Kennedy had met the day before with the producer to discuss the set design and camera placement. Nixon, just out of the hospital after a painful knee injury, did not take advantage of this opportunity and during the debate looked at the reporters asking questions and not at the camera. Kennedy wore a blue suit and shirt to cut down on glare and appeared sharply focused against the gray studio background. Nixon wore a light-colored suit that blended into the gray background; in combination with the harsh studio lighting that left Nixon perspiring, he offered a less-than-commanding presence. By contrast, Kennedy appeared relaxed, tanned, and telegenic, looking into the camera whilst answering questions.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Selverstone |first1=Marc J. |title=The Campaign and Election of 1960 |url=https://millercenter.org/president/kennedy/campaigns-and-elections |website=University of Virginia: Miller Center |date=October 4, 2016 |access-date=October 29, 2023 |archive-date=April 29, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170429092444/https://millercenter.org/president/kennedy/campaigns-and-elections |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="auto2"/> It is often claimed that television viewers overwhelmingly believed Kennedy, appearing to be the more attractive of the two, had won, while radio listeners (a smaller audience) thought Nixon had defeated him.<ref name="museum.tv"/><ref>{{cite episode|title=Nixon|series=American Experience|series-link=American Experience|network=]|station=]|date=October 15, 1990|season=3|number=2|url=https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/nixon/|access-date=June 15, 2022|archive-date=June 15, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220615213326/https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/nixon/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite episode|title=JFK (Part 1)|series=American Experience|network=PBS|station=WGBH|date=November 11, 2013|season=25|number=7|url=https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/jfk/|access-date=September 24, 2019|archive-date=September 25, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190925003921/https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/jfk/|url-status=live}}</ref> However, only one poll split TV and radio voters like this and the methodology was poor.<ref name="dbk1">{{cite journal | url = https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0362331916300556 | title = Debunking Nixon's radio victory in the 1960 election: Re-analyzing the historical record and considering currently unexamined polling data | last1 = Bruschke | first1 = John | last2 = Laura | first2 = Divine | date = March 2017 | journal = The Social Science Journal | volume = 54 | issue = 1 | pages = 67–75 | doi = 10.1016/j.soscij.2016.09.007 | s2cid = 151390817 | access-date = October 22, 2022 | archive-date = October 22, 2022 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20221022224031/https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0362331916300556 | url-status = live }}</ref> Pollster ] concluded that the debates raised interest, boosted turnout, and gave Kennedy an extra two million votes, mostly as a result of the first debate.<ref>{{cite book |last1=White |first1=Theodore H. |title=The Making of the President, 1960 |date=1961 |page=294}}</ref> The debates are now considered a milestone in American political history—the point at which the medium of television began to play a dominant role.<ref name="Jean3">{{cite web | url = http://www.airpower.maxwell.af.mil/airchronicles/aureview/1967/mar-apr/smith.html | title = Kennedy and Defense The formative years | access-date = September 18, 2007 | last = Edward Smith | first = Jean | date = March 1967 | work = Air University Review | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20081212113925/http://www.airpower.maxwell.af.mil/airchronicles/aureview/1967/mar-apr/smith.html | archive-date = December 12, 2008 | url-status = dead }}</ref> | ||

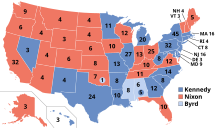

| ] | |||

| Kennedy's campaign gained momentum after the first debate, and he pulled slightly ahead of Nixon in most polls. On ], Kennedy defeated Nixon in one of the closest presidential elections of the 20th century. In the national popular vote, ], Kennedy led Nixon by just two-tenths of one percent (49.7% to 49.5%), while in the ], he won 303 votes to Nixon's 219 (269 were needed to win).{{sfn|Dudley|Shiraev|2008|p=83}} Fourteen electors from Mississippi and Alabama refused to support Kennedy because of his support for the ]; they voted for Senator ] of Virginia, as did an elector from Oklahoma.{{sfn|Dudley|Shiraev|2008|p=83}} Forty-three years old, Kennedy was the ] ever elected to the presidency (though ] was a year younger when he succeeded to the presidency after the ] in 1901).{{sfn|Reeves|1993|p=21}} | |||

| ==Presidency (1961–1963)== | |||

| {{Main|Presidency of John F. Kennedy}} | |||

| {{For timeline|Timeline of the John F. Kennedy presidency}} | |||

| ] ] administers the ] to Kennedy at ], January 20, 1961.]] | |||

| Kennedy was sworn in as the 35th president at noon on January 20, 1961. In ], he spoke of the need for all Americans to be active citizens: "Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country." He asked the nations of the world to join to fight what he called the "common enemies of man: tyranny, poverty, disease, and war itself."<ref name="JFKlibrary.org Inaugural Address">{{cite web|title=Inaugural Address |url=http://www.jfklibrary.org/Research/Ready-Reference/JFK-Quotations/Inaugural-Address.aspx |date=January 20, 1961 |first=John F. |last=Kennedy |publisher=] |access-date=February 22, 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120111193541/http://www.jfklibrary.org/Research/Ready-Reference/JFK-Quotations/Inaugural-Address.aspx |archive-date=January 11, 2012 }}</ref> He added: | |||

| <blockquote>All this will not be finished in the first one hundred days. Nor will it be finished in the first one thousand days, nor in the life of this Administration, nor even perhaps in our lifetime on this planet. But let us begin." In closing, he expanded on his desire for greater internationalism: "Finally, whether you are citizens of America or citizens of the world, ask of us here the same high standards of strength and sacrifice which we ask of you.<ref name="JFKlibrary.org Inaugural Address"/></blockquote> | |||

| The address reflected Kennedy's confidence that his administration would chart a historically significant course in both domestic policy and foreign affairs. The contrast between this optimistic vision and the pressures of managing daily political realities would be one of the main tensions of the early years of his administration.{{sfn|Kempe|2011|p=52}} | |||

| Kennedy scrapped the decision-making structure of Eisenhower,{{sfn|Reeves|1993|p=22}} preferring an organizational structure of a wheel with all the spokes leading to the president; he was willing to make the increased number of quick decisions required in such an environment.{{sfn|Reeves|1993|pp=23, 25}} Though the cabinet remained important, Kennedy generally relied more on his staffers within the ].{{sfn|Giglio|2006|pp=31–32, 35}} In spite of concerns over ], Kennedy's father insisted that Robert Kennedy become ], and the younger Kennedy became the "assistant president" who advised on all major issues.<ref>{{cite news|title=Bobby Kennedy: Is He the 'Assistant President'?|url=https://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2015/06/05/bobby-kennedy-is-he-the-assistant-president|publisher=U.S. News & World Report|date=February 19, 1962|access-date=January 25, 2024|archive-date=September 15, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160915234045/http://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2015/06/05/bobby-kennedy-is-he-the-assistant-president|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ===Foreign policy=== | |||

| {{main|Foreign policy of the John F. Kennedy administration}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ====Cold War and flexible response==== | |||

| Kennedy's foreign policy was dominated by American confrontations with the Soviet Union, manifested by proxy contests in the global state of tension known as the ]. Like his predecessors, Kennedy adopted the policy of ] to stop the spread of communism.{{Sfn|Herring|2008|pp=704–705}} Fearful of the possibility of ], Kennedy implemented a defense strategy known as ]. This strategy relied on multiple options for responding to the Soviet Union, discouraged ], and encouraged ].{{sfn|Brinkley|2012|pp=76–77}}<ref>{{cite web |title=1961–1968: The Presidencies of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson |url=https://history.state.gov/milestones/1961-1968/foreword |website=U.S. Department of State |access-date=November 19, 2023 |archive-date=February 16, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240216105026/https://history.state.gov/milestones/1961-1968/foreword |url-status=live }}</ref> In contrast to Eisenhower's warning about the perils of the ], Kennedy focused on rearmament. From 1961 to 1964 the number of ] increased by 50 percent, as did the number of ] bombers to deliver them.<ref>Stephen G Rabe, "John F. Kennedy" in Timothy J Lynch, ed., "The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Military and Diplomatic History" (2013) 1:610–615.</ref> | |||

| In January 1961, ] ] declared his support for ]. Kennedy interpreted this step as a direct threat to the "free world."<ref>{{cite book | last = Larres| first = Klaus|author2=Ann Lane|title =The Cold War: the essential readings| publisher = Wiley-Blackwell|year = 2001| page = 103| isbn = 978-0-631-20706-1}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |last1=Schlight |first1=John |title=A War Too Long: The USAF in Southeast Asia 1961-1975 |url=https://media.defense.gov/2010/May/25/2001330271/-1/-1/0/a_war_too_long.pdf |website=U.S. Department of Defense |access-date=27 January 2024 |archive-date=January 27, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240127154428/https://media.defense.gov/2010/May/25/2001330271/-1/-1/0/a_war_too_long.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ====Decolonization and the Congo Crisis==== | |||

| ] in 1962]] | |||

| Between 1960 and 1963, ] gained independence as the process of ] continued. Kennedy set out to woo the leaders and people of the "]," expanding economic aid and appointing knowledgeable ambassadors.{{Sfn|Herring|2008|pp=711–712}} His administration established the ] program and the ] to provide aid to ]. The Food for Peace program became a central element in American foreign policy, and eventually helped many countries to develop their economies and become commercial import customers.<ref>Robert G. Lewis, "What Food Crisis?: Global Hunger and Farmers' Woes." ''World Policy Journal'' 25.1 (2008): 29–35. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200109103541/https://www.jstor.org/stable/40210191 |date=January 9, 2020 }}</ref> | |||

| During the election campaign, Kennedy attacked the Eisenhower administration for losing ground on the African continent,<ref>Michael O'Brien, ''John F. Kennedy: A biography'' (2005) pp. 867–68.</ref> and stressed that the U.S. should be on the side of anti-colonialism and self-determination.<ref name="auto1">{{cite web |title=John F. Kennedy and African Independence |url=https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/john-f-kennedy-and-african-independence |website=John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum |access-date=November 19, 2023 |archive-date=November 12, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231112061214/https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/john-f-kennedy-and-african-independence |url-status=live }}{{PD-notice}}</ref> Kennedy considered the ] to be among the most important foreign policy issues facing his presidency, and he supported a ] that prevented the secession of ].{{sfn|Giglio|2006|pp=239–242}} ], leader of Katanga, declared its independence from the Congo and the Soviet Union responded by sending weapons and technicians to underwrite their struggle.<ref name="auto1"/> On October 2, 1962, Kennedy signed United Nations bond issue bill to ensure U.S. assistance in financing UN peacekeeping operations in the Congo and elsewhere.<ref>{{cite web |title=Remarks on signing U.N. Loan Bill, 2 October 1962 |url=https://www.jfklibrary.org/asset-viewer/archives/JFKPOF/040/JFKPOF-040-031 |website=John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum |access-date=November 19, 2023 |archive-date=November 19, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231119222114/https://www.jfklibrary.org/asset-viewer/archives/JFKPOF/040/JFKPOF-040-031 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ] volunteers on August 28, 1961]] | |||

| ====Peace Corps==== | |||

| {{main|Peace Corps}} | |||

| In one of his first presidential acts, Kennedy signed ] 10924 that officially started the ]. He named his brother-in-law, ], as its first director.{{sfn|Dallek|2003|pp=338–339}} Through this program, Americans volunteered to help developing countries in fields like education, farming, health care, and construction.<ref>{{cite web |title=The Peace Corps: Traveling The World To Live, Work, And Learn |url=https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/education/teachers/curricular-resources/the-peace-corps-traveling-the-world-to-live-work-and-learn |website=John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum |access-date=31 January 2024 |archive-date=January 31, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240131223635/https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/education/teachers/curricular-resources/the-peace-corps-traveling-the-world-to-live-work-and-learn |url-status=live }}</ref> Kennedy believed that countries that received Peace Corps volunteers were less likely to succumb to a communist revolution.<ref>{{cite web |title=Kennedy's Global Challenges |url=https://www.ushistory.org/us/56c.asp |website=U.S. History: From Pre-Columbian to the New Millennium. |access-date=November 19, 2023 |archive-date=November 19, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231119222120/https://www.ushistory.org/us/56c.asp |url-status=live }}</ref> ] (present-day ]) and ] were the first countries to participate.<ref>{{cite web |title=Peace Corps |url=https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/peace-corps |website=John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum |access-date=January 27, 2024 |archive-date=December 2, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231202085121/https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/peace-corps |url-status=live }}</ref> The organization grew to 5,000 members by March 1963 and 10,000 the year after.{{sfn|Schlesinger|2002|pp=606–607}} Since 1961, over 200,000 Americans have joined the Peace Corps, representing 139 countries.<ref>{{cite book| last1 = Meisler | first1 = Stanley | title = When the World Calls: The Inside Story of the Peace Corps and Its First Fifty Years | publisher = Beacon Press | year = 2011 | isbn = 978-0-8070-5049-1 | url = https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780807050491 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url = https://www.peacecorps.gov/news/fast-facts/| title = Peace Corps, Fast Facts | access-date = August 2, 2016 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160802133017/https://www.peacecorps.gov/news/fast-facts/ | archive-date=August 2, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| ====Vienna Summit and the Berlin Wall==== | |||

| {{see also|Vienna summit|Berlin Crisis of 1961}} | |||

| Kennedy anxiously anticipated a summit with Nikita Khrushchev. The proceedings for the summit got off to a problematic start when Kennedy reacted aggressively to a routine Khrushchev speech on Cold War confrontation in early 1961. The speech was intended for domestic audiences in the Soviet Union, but Kennedy interpreted it as a personal challenge. His mistake helped raise tensions going into the ].{{sfn|Kempe|2011|pp=76–78}} The summit would cover several topics, but both leaders knew that the most contentious issue would be ], which had been divided in two with the start of the Cold War. The enclave of ] lay within Soviet-allied ], but was supported by the U.S. and other Western powers. The Soviets wanted to reunify Berlin under the control of East Germany, partly due to the large number of East Germans who had fled to West Berlin.{{sfn|Brinkley|2012|pp=74, 77–78}} | |||

| ] ] in ] in June 1961]] | |||

| On June 4, 1961, Kennedy met with Khrushchev in Vienna and left the meeting angry and disappointed that he had allowed the premier to bully him, despite the warnings he had received. Khrushchev, for his part, was impressed with the president's intelligence but thought him weak. Kennedy did succeed in conveying the bottom line to Khrushchev on the most sensitive issue before them, a proposed treaty between Moscow and ]. He made it clear that any treaty interfering with U.S. access rights in West Berlin would be regarded as an act of war.{{sfn|Reeves|1993|pp=161–171}} Shortly after Kennedy returned home, the Soviet Union announced its plan to sign a treaty with East Berlin, abrogating any third-party occupation rights in either sector of the city. Kennedy assumed that his only option was to prepare the country for nuclear war, which he thought had a one-in-five chance of occurring.{{sfn|Reeves|1993|p=175}} | |||

| In the weeks immediately following the summit, more than 20,000 people ] to the western sector, reacting to statements from the Soviet Union. Kennedy began intensive meetings on the Berlin issue, where ] took the lead in recommending a military buildup alongside NATO allies.{{sfn|Reeves|1993|p=185}} In a July 1961 speech, Kennedy announced his decision to add $3.25 billion (equivalent to ${{Inflation|US|3.25|1961|r=2}} billion in {{Inflation-year|US}}) to the defense budget, along with over 200,000 additional troops, stating that an attack on West Berlin would be taken as an attack on the U.S. The speech received an 85% approval rating.{{sfn|Reeves|1993|p=201}} | |||

| A month later, both the Soviet Union and East Berlin began blocking any further passage of East Germans into West Berlin and erected ] fences, which were quickly upgraded to the ]. Kennedy acquiesced to the wall, though he sent Vice President Johnson to West Berlin to reaffirm U.S. commitment to the enclave's defense. In the following months, in a sign of rising Cold War tensions, both the U.S. and the Soviet Union ended a moratorium on nuclear weapon testing.{{sfn|Giglio|2006|pp=85–86}} A brief stand-off between U.S. and Soviet tanks occurred at ] in October following a dispute over free movement of Allied personnel. The ] was defused largely through a backchannel communication the Kennedy administration had set up with Soviet spy ].{{sfn|Kempe|2011|pp=}} In remarks to his aides on the Berlin Wall, Kennedy noted that "it's not a very nice solution, but a wall is a hell of a lot better than a war."<ref>{{cite book |last1=Updegrove |first1=Mark K. |title=Incomparable Grace: JFK in the Presidency |date=2022 |publisher=Penguin Publishing Group |page=118}}</ref> | |||

| ====Bay of Pigs Invasion==== | |||

| {{main|Bay of Pigs Invasion}} | |||

| ] at Miami's ]; {{ca|December 29, 1962}}.]] | |||

| The Eisenhower administration had created a plan to overthrow ]'s regime though an invasion of Cuba by a counter-revolutionary insurgency composed of U.S.-trained, anti-Castro ]s{{sfn|Schlesinger|2002|pp=233, 238}}{{sfn|Gleijeses|1995}} led by ] paramilitary officers.{{sfn|Reeves|1993|pp=69–73}} Kennedy had campaigned on a hardline stance against Castro, and when presented with the plan that had been developed under the Eisenhower administration, he enthusiastically adopted it regardless of the risk of inflaming tensions with the Soviet Union.<ref name="fiftyyearslater">{{cite news|title=50 Years Later: Learning From The Bay Of Pigs|url=https://www.npr.org/2011/04/17/135444482/50-years-later-learning-from-the-bay-of-pigs|access-date=September 1, 2016|publisher=NPR|date=April 17, 2011|archive-date=November 1, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191101111423/https://www.npr.org/2011/04/17/135444482/50-years-later-learning-from-the-bay-of-pigs|url-status=live}}</ref> Kennedy approved the final invasion plan on April 4, 1961.<ref>Quesada, Alejandro de (2009). ''The Bay of Pigs: Cuba 1961''. Elite series #166. Illustrated by Stephen Walsh. Osprey Publishing. p. 17.</ref> | |||

| On April 15, 1961, eight CIA-supplied ] bombers left Nicaragua to bomb Cuban airfields. The bombers missed many of their targets, leaving most of Castro's air force intact.<ref>{{cite web |title=The Bay of Pigs |url=https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/the-bay-of-pigs |website=John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum |access-date=November 19, 2023 |archive-date=February 23, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210223162426/https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/the-bay-of-pigs |url-status=live }} {{PD-notice}}</ref> On April 17, the 1,500 U.S.-trained Cuban exile invasion force, known as ], landed at beaches along the ] and immediately came under heavy fire.{{sfn|Reeves|1993|pp=71, 673}} The goal was to spark a widespread popular uprising against Castro, but no such uprising occurred.{{sfn|Brinkley|2012|pp=68–69}} No U.S. air support was provided.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Voss |first1=Michael |title=Bay of Pigs: The 'perfect failure' of Cuba invasion |work=BBC News |date=April 14, 2011 |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-13066561 |access-date=November 26, 2023 |archive-date=December 18, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231218143923/https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-13066561 |url-status=live }}</ref> The invading force was defeated within two days by the ];<ref>{{cite web |title=The Bay of Pigs Invasion and its Aftermath, April 1961–October 1962 |url=https://history.state.gov/milestones/1961-1968/bay-of-pigs#:~:text=Launched%20from%20Guatemala%2C%20the%20attack,the%20direct%20command%20of%20Castro. |website=U.S. Department of State |access-date=November 26, 2023 |archive-date=August 23, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160823123217/https://history.state.gov/milestones/1961-1968/bay-of-pigs#:~:text=Launched%20from%20Guatemala%2C%20the%20attack,the%20direct%20command%20of%20Castro. |url-status=live }}</ref> 114 were killed and Kennedy was forced to negotiate for the release of the 1,189 survivors.<ref>{{cite web |title=In Echo Park Many Local Cubans Celebrate Death Of Former President Fidel Castro |url=https://www.cbsnews.com/losangeles/news/in-echo-park-many-local-cubans-celebrate-death-of-former-president-fidel-castro/ |website=CBS News |date=November 26, 2016 |access-date=November 26, 2023 |archive-date=November 26, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231126173920/https://www.cbsnews.com/losangeles/news/in-echo-park-many-local-cubans-celebrate-death-of-former-president-fidel-castro/ |url-status=live }}</ref> After twenty months, Cuba released the captured exiles in exchange for a ransom of $53 million worth of food and medicine.{{sfn|Schlesinger|2002|pp=268–294, 838–839}} The incident made Castro wary of the U.S. and led him to believe that another invasion would take place.<ref>], "Bay of Pigs: The Unanswered Questions", ''The Nation'', April 13, 1964.</ref> | |||

| Biographer ] said that Kennedy focused primarily on the political repercussions of the plan rather than military considerations. When it proved unsuccessful, he was convinced that the plan was a setup to make him look bad.{{sfn|Reeves|1993|pp=95–97}} He took responsibility for the failure, saying, "We got a big kick in the leg and we deserved it. But maybe we'll learn something from it."{{sfn|Schlesinger|2002|pp=290, 295}} Kennedy's approval ratings climbed afterwards, helped in part by the vocal support given to him by Nixon and Eisenhower.{{sfn|Dallek|2003|pp=370–371}} He appointed Robert Kennedy to help lead a committee to examine the causes of the failure.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Hayes|first=Matthew A.|date=2019|title=Robert Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis: A Reassertion of Robert Kennedy's Role as the President's 'Indispensable Partner' in the Successful Resolution of the Crisis|journal=History|language=en|volume=104|issue=361|pages=473–503|doi=10.1111/1468-229X.12815|s2cid=164907501|issn=1468-229X|url=https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10075581/1/Hayes_%20Robert%20Kennedy%20and%20the%20Cuban%20Missile%20Crisis%20Final%20Accepted%20Manuscript.pdf|access-date=March 31, 2024|archive-date=December 27, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211227173632/https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10075581/1/Hayes_%20Robert%20Kennedy%20and%20the%20Cuban%20Missile%20Crisis%20Final%20Accepted%20Manuscript.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> The Kennedy administration ] and convinced the ] (OAS) to expel Cuba.{{Sfn|Herring|2008|pp=707–708}} | |||

| ====Operation Mongoose==== | |||

| In late 1961, the White House formed the Special Group (Augmented), headed by Robert Kennedy and including ], Secretary ], and others. The group's objective—to overthrow Castro via espionage, sabotage, and other covert tactics—was never pursued.{{sfn|Reeves|1993|p=264}} In November 1961, he authorized ].<ref name="eu.usatoday.com">{{cite web |url=https://eu.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2017/10/30/u-s-planned-261-000-troop-invasion-force-cuba-newly-released-documents-show/813376001/ |title=U.S. planned massive Cuba invasion force, the kidnapping of Cuban officials |work=USA Today |date=October 30, 2017 |access-date=April 15, 2019 |archive-date=April 12, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190412004346/https://eu.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2017/10/30/u-s-planned-261-000-troop-invasion-force-cuba-newly-released-documents-show/813376001/ |url-status=live }}</ref> In March 1962, Kennedy rejected ], proposals for ] attacks against American military and civilian targets,<ref name="1962USJCOS">{{cite web|url=https://archive.org/details/1962USJointChiefsOfStaffOperationNorthwoodsUnclassifiedDocument/page/n11|title=1962 US Joint Chiefs Of Staff Operation Northwoods Unclassified Document Bolsheviks NWO|date=1962|website=Internet Archive}}</ref> and blaming them on the Cuban government to gain approval for a war against Cuba. However, the administration continued to plan for an invasion of Cuba in the summer of 1962.<ref name="eu.usatoday.com"/> | |||

| ====Cuban Missile Crisis==== | |||

| {{main|Cuban Missile Crisis}} | |||

| ] in the Oval Office; {{ca|October 23, 1962}}.]] | |||

| In the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs invasion, Khrushchev increased economic and military assistance to Cuba.{{sfn|Giglio|2006|pp=203–205}} The Soviet Union planned to allocate in Cuba 49 ]s, 32 ]s, 49 light ] bombers and about 100 ].<ref>{{cite book | last = Giglio| first =James|author2=Stephen G. Rabe|title =Debating the Kennedy presidency| url = https://archive.org/details/debatingkennedyp00gigl_480| url-access = limited| publisher = Rowman & Littlefield|year = 2003| page = | isbn = 978-0-7425-0834-7}}</ref> The Kennedy administration viewed the growing ] with alarm, fearing that it could eventually pose a threat to the U.S.{{sfn|Brinkley|2012|pp=113–114}} On October 14, 1962, CIA ] spy planes ] of the Soviets' construction of intermediate-range ballistic missile sites in Cuba. The photos were shown to Kennedy on October 16; a consensus was reached that the missiles were offensive in nature and posed an immediate nuclear threat.{{sfn|Reeves|1993|p=345}} | |||

| Kennedy faced a dilemma: if the U.S. attacked the sites, it might lead to nuclear war with the Soviet Union, but if the U.S. did nothing, it would be faced with the increased threat from close-range nuclear weapons (positioned approximately 90 mi (140 km) away from the Florida coast).<ref>{{cite web |title=President John F. Kennedy - Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962 |url=https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/eyewitness/html.php?section=26#:~:text=On%20October%2016%2C%201962%2C%20President,come%20on%20very%20short%20notice. |website=National Archives |access-date=30 January 2024 |archive-date=September 28, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230928100637/https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/eyewitness/html.php?section=26#:~:text=On%20October%2016%2C%201962%2C%20President,come%20on%20very%20short%20notice. |url-status=live }}</ref> The U.S. would also appear to the world as less committed to the defense of the Western Hemisphere. On a personal level, Kennedy needed to show resolve in reaction to Khrushchev, especially after the Vienna summit.{{sfn|Reeves|1993|p=245}} To deal with the crisis, he formed an ad-hoc body of key advisers, later known as ], that met secretly between October 16 and 28.{{sfn|Giglio|2006|pp=207–208}} | |||

| More than a third of ] (NSC) members favored an unannounced air assault on the missile sites, but some saw this as "] in reverse."{{sfn|Reeves|1993|p=387}} There was some concern from the international community (asked in confidence) that the assault plan was an overreaction given that Eisenhower had placed ] missiles in Italy and Turkey in 1958. It also could not be assured that the assault would be 100% effective.{{sfn|Reeves|1993|p=388}} In concurrence with a majority vote of the NSC, Kennedy decided on a ] (or "quarantine"). On October 22, after privately informing the cabinet and leading members of Congress about the situation, Kennedy announced the naval blockade on national television and warned that U.S. forces would seize "offensive weapons and associated materiel" that Soviet vessels might attempt to deliver to Cuba.{{sfn|Reeves|1993|p=389}} | |||

| ]; {{ca|October 1962}}.]] | |||

| The U.S. Navy would stop and inspect all Soviet ships arriving off Cuba, beginning October 24. Several Soviet ships approached the blockade line, but they stopped or reversed course.{{sfn|Giglio|2006|p=220}} The OAS gave unanimous support to the removal of the missiles. Kennedy exchanged two sets of letters with Khrushchev, to no avail.{{sfn|Reeves|1993|p=390}} UN Secretary General ] requested both parties to reverse their decisions and enter a cooling-off period. Khrushchev agreed, but Kennedy did not.{{sfn|Reeves|1993|p=403}} Kennedy managed to preserve restraint when a Soviet missile unauthorizedly downed a U.S. Lockheed U-2 reconnaissance aircraft over Cuba, killing pilot ].<ref>{{cite web |title=The World on the Brink: John F. Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis |url=https://microsites.jfklibrary.org/cmc/oct27/ |website=John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum |access-date=November 26, 2023 |archive-date=November 24, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231124154618/https://microsites.jfklibrary.org/cmc/oct27/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| At the president's direction, Robert Kennedy privately informed Soviet Ambassador ] that the U.S. would remove the Jupiter missiles from Turkey "within a short time after this crisis was over."{{sfn|Giglio|2006|pp=225–226}} On October 28, Khrushchev agreed to dismantle the missile sites, subject to UN inspections.{{sfn|Reeves|1993|p=426}} The U.S. publicly promised never to invade Cuba and privately agreed to remove its Jupiter missiles from Italy and Turkey, which were by then obsolete and had been supplanted by submarines equipped with ] missiles.{{sfn|Kenney|2000|pp=184–186}} | |||

| In the aftermath, a ] was established to ensure clear communications between the leaders of the two countries.{{Sfn|Herring|2008|p=723}} This crisis brought the world closer to nuclear war than at any point before or after, but "the humanity" of Khrushchev and Kennedy prevailed.{{sfn|Kenney|2000|p=189}} The crisis improved the image of American willpower and the president's credibility. Kennedy's approval rating increased from 66% to 77% immediately thereafter.{{sfn|Reeves|1993|p=425}} | |||

| ====Latin America and communism==== | |||

| {{further|Presidency of John F. Kennedy#Latin America}} | |||

| {{see also|Alliance for Progress}} | |||

| ] with Venezuelan President ]]] | |||

| Believing that "those who make peaceful revolution impossible, will make violent revolution inevitable,"<ref>JFK's "Address on the First Anniversary of the Alliance for Progress", White House reception for diplomatic cors of the Latin American republics, March 13, 1962. ''Public Papers of the Presidents'' – John F. Kennedy (1962), p. 223.</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=http://name.umdl.umich.edu/4730892.1962.001|title=John F. Kennedy: 1962 : containing the public messages, speeches, and statements of the president, January 20 to December 31, 1962.|last=Kennedy|first=John F. (John Fitzgerald)|date=2005|access-date=December 29, 2018|archive-date=March 31, 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240331040145/https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=ppotpus;idno=4730892.1962.001|url-status=live}}</ref> Kennedy sought to contain the perceived threat of communism in Latin America by establishing the ], which sent aid to some countries and sought greater ] standards in the region.{{sfn|Schlesinger|2002|pp=788, 789}} In response to Kennedy's plea, Congress voted for an initial grant of $500 million in May 1961.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Glass |first1=Andrew |title=JFK proposes an Alliance for Progress for Latin America, March 13, 1961 |url=https://www.politico.com/story/2019/03/13/jfk-proposes-an-alliance-for-progress-for-latin-america-march-13-1961-1214880 |website=Politico |date=March 13, 2019 |access-date=November 26, 2023 |archive-date=November 26, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231126175004/https://www.politico.com/story/2019/03/13/jfk-proposes-an-alliance-for-progress-for-latin-america-march-13-1961-1214880 |url-status=live }}</ref> The Alliance for Progress supported the construction of housing, schools, airports, hospitals, clinics and water-purification projects as well as the distribution of free textbooks to students.<ref name="auto">{{cite web |title=Alliance for Progress |url=https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/alliance-for-progress |website=John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum |access-date=November 19, 2023 |archive-date=November 12, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231112173320/https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/alliance-for-progress |url-status=live }}{{PD-notice}}</ref> However, the program did not meet many of its goals. Massive land reform was not achieved; populations more than kept pace with gains in health and welfare; and according to one study, only 2 percent of economic growth in 1960s Latin America directly benefited the poor.<ref>{{cite web |title=Alliance for Progress |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Alliance-for-Progress |website=Encyclopedia Britannica |access-date=November 19, 2023 |archive-date=November 18, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231118175215/https://www.britannica.com/topic/Alliance-for-Progress |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Alliance for Progress and Peace Corps, 1961–1969 |url=https://history.state.gov/milestones/1961-1968/alliance-for-progress |website=United States Department of State |access-date=November 19, 2023 |archive-date=November 18, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231118180616/https://history.state.gov/milestones/1961-1968/alliance-for-progress |url-status=live }}</ref> U.S. presidents after Kennedy were less supportive of the program and by 1973, the permanent committee established to implement the Alliance was disbanded by the OAS.<ref name="auto"/> | |||

| The Eisenhower administration, through the CIA, had begun formulating plans to assassinate Castro in Cuba and ] in the ]. When Kennedy took office, he privately instructed the CIA that any plan must include ] by the U.S. His public position was in opposition.{{sfn|Reeves|1993|pp=140–142}} In June 1961, the Dominican Republic's leader was assassinated; in the days following, Undersecretary of State ] led a cautious reaction by the nation. Robert Kennedy, who saw an opportunity for the U.S., called Bowles "a gutless bastard" to his face.{{sfn|Reeves|1993|p=152}} | |||

| ====Laos==== | |||

| {{see also|Laotian Civil War}} | |||

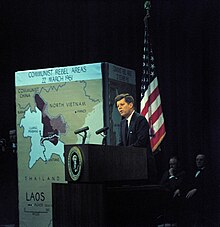

| After the election, Eisenhower emphasized to Kennedy that the communist threat in Southeast Asia required priority; Eisenhower considered ] to be "the cork in the bottle" in regards to the regional threat.{{sfn|Reeves|1993|p=75}} In March 1961, Kennedy voiced a change in policy from supporting a "free" Laos to a "neutral" Laos, indicating privately that ] should be deemed America's tripwire for communism's spread in the area.{{sfn|Reeves|1993|p=75}} Though he was unwilling to commit U.S. forces to a major military intervention in Laos, Kennedy did approve ] designed to defeat Communist insurgents through bombing raids and the recruitment of the ].{{sfn|Patterson|1996|p=498}} | |||

| ====Vietnam==== | |||

| {{further|Presidency of John F. Kennedy#Vietnam}} | |||

| {{see also|Vietnam War}} | |||

| ] | |||

| During his presidency, Kennedy continued policies that provided political, economic, and military support to the ]ese government.{{sfn|Dunnigan|Nofi|1999|p=257}} Vietnam had been divided into a communist North Vietnam and a non-communist South Vietnam after the ], but Kennedy escalated American involvement in Vietnam in 1961 by financing the ], increasing the number of U.S. ] above the levels of the Eisenhower administration, and authorizing U.S. helicopter units to provide support to South Vietnamese forces.{{sfn|Giglio|2006|pp=256–261}} On January 18, 1962, Kennedy formally authorized escalated involvement when he signed the National Security Action Memorandum (NSAM) – "Subversive Insurgency (War of Liberation)."{{sfn|Reeves|1993|p=281}} ], a large-scale aerial defoliation effort using the herbicide ], began on the roadsides of South Vietnam to combat ].{{sfn|Reeves|1993|p=259}}<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/07/agent-orange-cambodia-laos-vietnam/591412/ | title=The U.S.'s Toxic Agent Orange Legacy | publisher=The Atlantic | date=July 20, 2019 | access-date=May 13, 2023 | first=Charles | last=Dunst | archive-date=October 14, 2019 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191014202833/https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/07/agent-orange-cambodia-laos-vietnam/591412/ | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Though Kennedy provided support for South Vietnam throughout his tenure% | |||

Revision as of 20:13, 11 April 2024

President of the United States from 1961 to 1963 Several terms redirect here. For the current Republican senator, see John Kennedy (Louisiana politician). For other uses, see John Kennedy (disambiguation), Jack Kennedy (disambiguation), JFK (disambiguation), and John F. Kennedy (disambiguation).

| John F. Kennedy | |

|---|---|

Oval Office portrait, 1963 Oval Office portrait, 1963 | |

| 35th President of the United States | |

| In office January 20, 1961 – November 22, 1963 | |

| Vice President | Lyndon B. Johnson |

| Preceded by | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Succeeded by | Lyndon B. Johnson |

| United States Senator from Massachusetts | |

| In office January 3, 1953 – December 22, 1960 | |

| Preceded by | Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin A. Smith II |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts's 11th district | |

| In office January 3, 1947 – January 3, 1953 | |

| Preceded by | James Michael Curley |

| Succeeded by | Tip O'Neill |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Fitzgerald Kennedy (1917-05-29)May 29, 1917 Brookline, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | November 22, 1963(1963-11-22) (aged 46) Dallas, Texas, U.S. |

| Manner of death | Assassination |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Jacqueline Bouvier (m. 1953) |

| Children | 4, including Caroline, John Jr., and Patrick |

| Parents | |

| Relatives | Kennedy family |

| Education | Harvard University (AB) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1941–1945 |

| Rank | Lieutenant |

| Unit |

|

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | |

|

John F. Kennedy's voice

Kennedy on the establishment of the Peace Corps Recorded March 1, 1961 | |

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to as JFK, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the youngest person elected president. Kennedy served at the height of the Cold War, and the majority of his foreign policy concerned relations with the Soviet Union and Cuba. A Democrat, Kennedy represented Massachusetts in both houses of the United States Congress prior to his presidency.

Born into the prominent Kennedy family in Brookline, Massachusetts, Kennedy graduated from Harvard University in 1940, joining the U.S. Naval Reserve the following year. During World War II, he commanded PT boats in the Pacific theater. Kennedy's survival following the sinking of PT-109 and his rescue of his fellow sailors made him a war hero and earned the Navy and Marine Corps Medal, but left him with serious injuries. After a brief stint in journalism, Kennedy represented a working-class Boston district in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1947 to 1953. He was subsequently elected to the U.S. Senate, serving as the junior senator for Massachusetts from 1953 to 1960. While in the Senate, Kennedy published his book, Profiles in Courage, which won a Pulitzer Prize. Kennedy ran in the 1960 presidential election. His campaign gained momentum after the first televised presidential debates in American history, and he was elected president, narrowly defeating Republican opponent Richard Nixon, the incumbent vice president.

Kennedy's presidency saw high tensions with communist states in the Cold War. He increased the number of American military advisers in South Vietnam, and the Strategic Hamlet Program began during his presidency. In 1961, he authorized attempts to overthrow the Cuban government of Fidel Castro in the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion and Operation Mongoose. In October 1962, U.S. spy planes discovered Soviet missile bases had been deployed in Cuba. The resulting period of tensions, termed the Cuban Missile Crisis, nearly resulted in nuclear war. In August 1961, after East German troops erected the Berlin Wall, Kennedy sent an army convoy to reassure West Berliners of U.S. support, and delivered one of his most famous speeches in West Berlin in June 1963. In 1963, Kennedy signed the first nuclear weapons treaty. He presided over the establishment of the Peace Corps, Alliance for Progress with Latin America, and the continuation of the Apollo program with the goal of landing a man on the Moon before 1970. He supported the civil rights movement but was only somewhat successful in passing his New Frontier domestic policies.

On November 22, 1963, Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. His vice president, Lyndon B. Johnson, assumed the presidency. Lee Harvey Oswald was arrested for the assassination, but he was shot and killed by Jack Ruby two days later. The FBI and the Warren Commission both concluded Oswald had acted alone, but conspiracy theories about the assassination persist. After Kennedy's death, Congress enacted many of his proposals, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Revenue Act of 1964. Kennedy ranks highly in polls of U.S. presidents with historians and the general public. His personal life has been the focus of considerable sustained interest following public revelations in the 1970s of his chronic health ailments and extramarital affairs. Kennedy is the most recent U.S. president to have died in office.

Early life and education

John Fitzgerald Kennedy was born outside Boston in Brookline, Massachusetts, on May 29, 1917, to Joseph P. Kennedy Sr., a businessman and politician, and Rose Kennedy (née Fitzgerald), a philanthropist and socialite. His paternal grandfather, P. J. Kennedy, was an East Boston ward boss and Massachusetts state legislator. Kennedy's maternal grandfather and namesake, John F. Fitzgerald, was a U.S. Congressman and two-term Mayor of Boston. All four of his grandparents were children of Irish immigrants. Kennedy had an older brother, Joseph Jr., and seven younger siblings: Rosemary, Kathleen, Eunice, Patricia, Robert, Jean, and Edward.

Kennedy's father amassed a private fortune and established trust funds for his nine children that guaranteed lifelong financial independence. His business kept him away from home for long stretches, but Joe Sr. was a formidable presence in his children's lives. He encouraged them to be ambitious, emphasized political discussions at the dinner table, and demanded a high level of academic achievement. John's first exposure to politics was touring the Boston wards with his grandfather Fitzgerald during his 1922 failed gubernatorial campaign. With Joe Sr.'s business ventures concentrated on Wall Street and Hollywood and an outbreak of polio in Massachusetts, the family decided to move from Boston to the Riverdale neighborhood of New York City in September 1927. Several years later, his brother Robert told Look magazine that his father left Boston because of job signs that read: "No Irish Need Apply." The Kennedys spent summers and early autumns at their home in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts, a village on Cape Cod, where they enjoyed swimming, sailing, and touch football. Christmas and Easter holidays were spent at their winter retreat in Palm Beach, Florida. In September 1930, Kennedy, then 13 years old, was sent to the Canterbury School in New Milford, Connecticut, for 8th grade. In April 1931, he had an appendectomy, after which he withdrew from Canterbury and recuperated at home.

In September 1931, Kennedy started attending Choate, a preparatory boarding school in Wallingford, Connecticut. Rose had wanted John and Joe Jr. to attend Catholic school, but Joe Sr. thought that if they were to compete in the political world, they needed to be with boys from prominent Protestant families. John spent his first years at Choate in his older brother's shadow and compensated with rebellious behavior that attracted a clique. Their most notorious stunt was exploding a toilet seat with a firecracker. In the next chapel assembly, the headmaster, George St. John, brandished the toilet seat and spoke of "muckers" who would "spit in our sea," leading Kennedy to name his group "The Muckers Club," which included roommate and lifelong friend Lem Billings. Kennedy graduated from Choate in June 1935, finishing 64th of 112 students. He had been the business manager of the school yearbook and was voted the "most likely to succeed."

Kennedy intended to study under Harold Laski at the London School of Economics, as his older brother had done. Ill health forced his return to the U.S. in October 1935, when he enrolled late at Princeton University but had to leave after two months due to gastrointestinal illness.

In September 1936, Kennedy enrolled at Harvard College. He wrote occasionally for The Harvard Crimson, the campus newspaper, but had little involvement with campus politics, preferring to concentrate on athletics and his social life. Kennedy played football and was on the JV squad during his sophomore year, but an injury forced him off the team, and left him with back problems that would plague him for the rest of his life. He won membership in the Hasty Pudding Club and the Spee Club, one of Harvard's elite "final clubs".

In July 1938, Kennedy sailed overseas with his older brother to work at the American embassy in London, where his father was serving as President Franklin D. Roosevelt's ambassador to the Court of St. James's. The following year, Kennedy traveled throughout Europe, the Soviet Union, the Balkans, and the Middle East in preparation for his Harvard senior honors thesis. He then went to Berlin, where a U.S. diplomatic representative gave him a secret message about war breaking out soon to pass on to his father, and to Czechoslovakia before returning to London on September 1, 1939, the day that Germany invaded Poland and World War II began. Two days later, the family was in the House of Commons for speeches endorsing the United Kingdom's declaration of war on Germany. Kennedy was sent as his father's representative to help with arrangements for American survivors of SS Athenia before flying back to the U.S. on his first transatlantic flight.

While Kennedy was an upperclassman at Harvard, he began to take his studies more seriously and developed an interest in political philosophy. He made the dean's list in his junior year. In 1940, Kennedy completed his thesis, "Appeasement in Munich", about British negotiations during the Munich Agreement. The thesis was released on July 24, under the title Why England Slept. The book was one of the first to offer information about the war and its origins, and quickly became a bestseller. In addition to addressing Britain's unwillingness to strengthen its military in the lead-up to the war, the book called for an Anglo-American alliance against the rising totalitarian powers. Kennedy became increasingly supportive of U.S. intervention in World War II, and his father's isolationist beliefs resulted in the latter's dismissal as ambassador.

In 1940, Kennedy graduated cum laude from Harvard with a Bachelor of Arts in government, concentrating on international affairs. That fall, he enrolled at the Stanford Graduate School of Business and audited classes, but he left after a semester to help his father complete his memoirs as an American ambassador. In early 1941, Kennedy toured South America.

U.S. Naval Reserve (1941–1945)

Kennedy planned to attend Yale Law School, but canceled when American entry into World War II seemed imminent. In 1940, Kennedy attempted to enter the army's Officer Candidate School. Despite months of training, he was medically disqualified due to his chronic back problems. On September 24, 1941, Kennedy, with the help of the director of the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) and the former naval attaché to Joe Sr., Alan Kirk, joined the United States Naval Reserve. He was commissioned an ensign on October 26, 1941, and joined the ONI staff in Washington, D.C.

In January 1942, Kennedy was assigned to the ONI field office at Headquarters, Sixth Naval District, in Charleston, South Carolina. His hope was to be the commander of a PT (patrol torpedo) boat, but his health problems seemed almost certain to prevent active duty. Kennedy's father intervened by providing misleading medical records and convincing PT officers that his presence would bring publicity to the fleet. Kennedy completed six months of training at the Naval Reserve Officer Training School in Chicago and at the Motor Torpedo Boat Squadrons Training Center in Melville, Rhode Island. His first command was PT-101 from December 7, 1942, until February 23, 1943. Unhappy to be assigned to the Panama Canal, far from the fighting, Kennedy appealed to U.S. Senator David Walsh of Massachusetts, who arranged for him to be assigned to the South Pacific.

Commanding PT-109 and PT-59

Main article: Patrol torpedo boat PT-109

In April 1943, Kennedy was assigned to Motor Torpedo Squadron TWO, and on April 24 he took command of PT-109, then based on Tulagi Island in the Solomons. On the night of August 1–2, in support of the New Georgia campaign, PT-109 and fourteen other PTs were ordered to block or repel four Japanese destroyers and floatplanes carrying food, supplies, and 900 Japanese soldiers to the Vila Plantation garrison on the southern tip of the Solomon's Kolombangara Island. Intelligence had been sent to Kennedy's Commander Thomas G. Warfield expecting the arrival of the large Japanese naval force that would pass on the evening of August 1. Of the 24 torpedoes fired that night by eight of the American PTs, not one hit the Japanese convoy. On that moonless night, Kennedy spotted a Japanese destroyer heading north on its return from the base of Kolombangara around 2:00 a.m., and attempted to turn to attack, when PT-109 was rammed suddenly at an angle and cut in half by the destroyer Amagiri, killing two PT-109 crew members. Avoiding surrender, the remaining crew swam towards Plum Pudding Island, 3.5 miles (5.6 km) southwest of the remains of PT-109, on August 2. Despite re-injuring his back in the collision, Kennedy towed a badly burned crewman to the island with a life jacket strap clenched between his teeth. From there, Kennedy and his subordinate, Ensign George Ross, made forays through the coral islands, searching for help. When they encountered an English-speaking native with a canoe, Kennedy carved his location on a coconut shell and requested a boat rescue. Seven days after the collision, with the coconut message delivered, the PT-109 crew were rescued.

Almost immediately, the PT-109 rescue became a highly publicized event. The story was chronicled by John Hersey in The New Yorker in 1944 (decades later it was the basis of a successful film). It followed Kennedy into politics and provided a strong foundation for his appeal as a leader. Hersey portrayed Kennedy as a modest, self-deprecating hero. For his courage and leadership, Kennedy was awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal, and the injuries he suffered during the incident qualified him for a Purple Heart.

After a month's recovery Kennedy returned to duty, commanding the PT-59. On November 2, Kennedy's PT-59 took part with two other PTs in the rescue of 40–50 marines. The 59 acted as a shield from shore fire as they escaped on two rescue landing craft at the base of the Warrior River at Choiseul Island, taking ten marines aboard and delivering them to safety. Under doctor's orders, Kennedy was relieved of his command on November 18, and sent to the hospital on Tulagi. By December 1943, with his health deteriorating, Kennedy left the Pacific front and arrived in San Francisco in early January 1944. After receiving treatment for his back injury at the Chelsea Naval Hospital in Massachusetts from May to December 1944, he was released from active duty. Beginning in January 1945, Kennedy spent three months recovering from his back injury at Castle Hot Springs, a resort and temporary military hospital in Arizona. On March 1, 1945, Kennedy retired from the Navy Reserve on physical disability and was honorably discharged with the full rank of lieutenant. When later asked how he became a war hero, Kennedy joked: "It was easy. They cut my PT boat in half."

On August 12, 1944, Kennedy's older brother, Joe Jr., a navy pilot, was killed on an air mission. His body was never recovered. The news reached the family's home in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts a day later. Kennedy felt that Joe Jr.'s reckless flight was partly an effort to outdo him. To console himself, Kennedy set out to assemble a privately published book of remembrances of his brother, As We Remember Joe.

Journalism (1945)

In April 1945, Kennedy's father, who was a friend of William Randolph Hearst, arranged a position for his son as a special correspondent for Hearst Newspapers; the assignment kept Kennedy's name in the public eye and "expose him to journalism as a possible career." That May he went to Berlin as a correspondent, covering the Potsdam Conference and other events.

U.S. House of Representatives (1947–1953)

Kennedy's elder brother Joe Jr. had been the family's political standard-bearer and had been tapped by their father to seek the presidency. After Joe's death, the assignment fell to JFK as the second eldest. Boston mayor Maurice J. Tobin discussed the possibility of John becoming his running mate in 1946 as a candidate for Massachusetts lieutenant governor, but Joe Sr. preferred a congressional campaign that could send John to Washington, where he could have national visibility.

At the urging of Kennedy's father, U.S. Representative James Michael Curley vacated his seat in the strongly Democratic 11th congressional district of Massachusetts to become mayor of Boston in 1946. Kennedy established legal residency at 122 Bowdoin Street across from the Massachusetts State House. Kennedy won the Democratic primary with 42 percent of the vote, defeating nine other candidates. According to Logevall, Joe Sr.

spent hours on the phone with reporters and editors, seeking information, trading confidences, and cajoling them into publishing puff pieces on John, ones that invariably played up his war record in the Pacific. He oversaw a professional advertising campaign that ensured ads went up in just the right places the campaign had a virtual monopoly on subway space, and on window stickers ("Kennedy for Congress") for cars and homes and was the force behind the mass mailing of Hersey's PT-109 article.

Though Republicans took control of the House in the 1946 elections, Kennedy defeated his Republican opponent in the general election, taking 73 percent of the vote.

Kennedy served in the House for six years, joining the influential Education and Labor Committee and the Veterans' Affairs Committee. He concentrated his attention on international affairs, supporting the Truman Doctrine as the appropriate response to the emerging Cold War. He also supported public housing and opposed the Labor Management Relations Act of 1947, which restricted the power of labor unions. Though not as vocally anti-communist as Joseph McCarthy, Kennedy supported the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, which required communists to register with the government, and he deplored the "loss of China." During a speech in Salem, Massachusetts on January 30, 1949, Kennedy denounced Truman and the State Department for contributing to the "tragic story of China whose freedom we once fought to preserve. What our young men had saved , our diplomats and our President have frittered away."

In November 1947, Kennedy delivered a speech in Congress supporting a $227 million aid package to Italy. He maintained that Italy was in danger from an "onslaught of the communist minority" and that the country was the "initial battleground in the communist drive to capture Western Europe." This speech was calculated to appeal to the large Italian-American voting bloc in Massachusetts as Kennedy was beginning to position himself for statewide office. To combat Soviet efforts to take control in Middle Eastern and Asian countries like Indochina, Kennedy wanted the United States to develop nonmilitary techniques of resistance that would not create suspicions of neoimperialism or add to the country's financial burden. The problem, as he saw it, was not simply to be anti-communist but to stand for something that these emerging nations would find appealing.

Having served as a boy scout during his childhood, Kennedy was active in the Boston Council from 1946 to 1955 as district vice chairman, member of the executive board, vice-president, and National Council Representative. Almost every weekend that Congress was in session, Kennedy would fly back to Massachusetts to give speeches to veteran, fraternal, and civic groups, while maintaining an index card file on individuals who might be helpful for a campaign for statewide office. Contemplating whether to run for the U.S. Senate or governor of Massachusetts, Kennedy abandoned interest in the latter, believing that the governor "sat in an office, handing out sewer contracts."

U.S. Senate (1953–1960)

See also: 1952 United States Senate election in Massachusetts and 1958 United States Senate election in Massachusetts

As early as 1949, Kennedy began preparing to run for the Senate in 1952 against Republican three-term incumbent Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. with the campaign slogan "KENNEDY WILL DO MORE FOR MASSACHUSETTS". Joe Sr. again financed his son's candidacy (persuading the Boston Post to switch its support to Kennedy by promising the publisher a $500,000 loan), while John's younger brother Robert emerged as campaign manager. Kennedy's mother and sisters contributed as highly effective canvassers by hosting a series of "teas" at hotels and parlors across Massachusetts to reach out to women voters. In the presidential election, Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower carried Massachusetts by 208,000 votes, but Kennedy narrowly defeated Lodge by 70,000 votes for the Senate seat. The following year, he married Jacqueline Bouvier.

Kennedy underwent several spinal operations over the next two years. Often absent from the Senate, he was at times critically ill and received Catholic last rites. During his convalescence in 1956, he published Profiles in Courage, a book about U.S. senators who risked their careers for their personal beliefs, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography in 1957. Rumors that this work was ghostwritten by his close adviser and speechwriter, Ted Sorensen, were confirmed in Sorensen's 2008 autobiography.

At the start of his first term, Kennedy focused on fulfilling the promise of his campaign to do "more for Massachusetts" than his predecessor. Although Kennedy's and Lodge's legislative records were similarly liberal, Lodge voted for the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 and Kennedy voted against it. On NBC's Meet the Press, Kennedy excoriated Lodge for not doing enough to prevent the increasing migration of manufacturing jobs from Massachusetts to the South, and blamed the right-to-work provision for giving the South an unfair advantage over Massachusetts in labor costs. In May 1953, Kennedy introduced "The Economic Problems of New England", a 36-point program to help Massachusetts industries such as fishing, textile manufacturing, watchmaking, and shipbuilding, as well as the Boston seaport. Kennedy's policy agenda included protective tariffs, preventing excessive speculation in raw wool, stronger efforts to research and market American fish products, an increase in the Fish and Wildlife Service budget, modernizing reserve-fleet vessels, tax incentives to prevent further business relocations, and the development of hydroelectric and nuclear power in Massachusetts. Kennedy's suggestions for stimulating the region's economy appealed to both parties by offering benefits to business and labor, and promising to serve national defense. Congress would eventually enact most of the program. Kennedy, a Massachusetts Audubon Society supporter, wanted to make sure that the shorelines of Cape Cod remained unsullied by industrialization. On September 3, 1959, Kennedy co-sponsored the Cape Cod National Seashore bill with his Republican colleague Senator Leverett Saltonstall.

As a senator, Kennedy quickly won a reputation for responsiveness to requests from constituents (i.e., co-sponsoring legislation to provide federal loans to help rebuild communities damaged by the 1953 Worcester tornado), except when the national interest was at stake. In 1954, Kennedy voted in favor of the Saint Lawrence Seaway which would connect the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean, despite opposition from Massachusetts politicians who argued that the project would hurt the Port of Boston economically. "His stand on the St. Lawrence project had the effect of making him a national figure," Ted Sorensen later remarked.

In 1956, Kennedy, aided by Kenneth O'Donnell and Larry O'Brien, gained control of the Massachusetts Democratic Party, and delivered the state delegation to the party's presidential nominee, Adlai Stevenson II, at the Democratic National Convention in August. Stevenson let the convention select the vice presidential nominee. Kennedy finished second in the balloting, losing to Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee, but receiving national exposure.

In 1957, Kennedy joined the Senate's Select Committee on Labor Rackets (also known as the McClellan Committee) with his brother Robert, who was chief counsel, to investigate racketeering in labor-management relations. The hearings attracted extensive radio and television coverage where the Kennedy brothers engaged in dramatic arguments with controversial labor leaders, including Jimmy Hoffa, of the Teamsters Union. The following year, Kennedy introduced a bill to prevent the expenditure of union dues for improper purposes or private gain; to forbid loans from union funds for illicit transactions; and to compel audits of unions, which would ensure against false financial reports. It was the first major labor relations bill to pass either house since the Taft–Hartley Act of 1947 and dealt largely with the control of union abuses exposed by the McClellan Committee but did not incorporate tough Taft–Hartley amendments requested by President Eisenhower. It survived Senate floor attempts to include Taft-Hartley amendments and passed but was rejected by the House. "Honest union members and the general public can only regard it as a tragedy that politics has prevented the recommendations of the McClellan committee from being carried out this year," Kennedy announced.

That same year, Kennedy joined the Senate's Foreign Relations Committee. There he supported Algeria's effort to gain independence from France and sponsored an amendment to the Mutual Defense Assistance Act that would provide aid to Soviet satellite nations. Kennedy also introduced an amendment to the National Defense Education Act in 1959 to eliminate the requirement that aid recipients sign a loyalty oath and provide supporting affidavits.

Kennedy cast a procedural vote against President Eisenhower's bill for the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and this was considered by some to be an appeasement of Southern Democratic opponents of the bill. Kennedy did vote for Title III of the act, which would have given the Attorney General powers to enjoin, but Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson agreed to let the provision die as a compromise measure. Kennedy also voted for the "Jury Trial Amendment." Many civil rights advocates criticized that vote as one which would weaken the act. A final compromise bill, which Kennedy supported, was passed in September 1957. As a senator from Massachusetts, which lacked a sizable Black population, Kennedy was not particularly sensitive to the problems of African Americans. Robert Kennedy later reflected, "We weren't thinking of the Negroes of Mississippi or Alabama—what should be done for them. We were thinking of what needed to be done in Massachusetts."

Kennedy's father was a strong supporter and friend of Senator Joseph McCarthy. Robert Kennedy worked for McCarthy's subcommittee as an assistant counsel, and McCarthy dated Kennedy's sister Patricia. Kennedy told historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr., "Hell, half my voters in Massachusetts look on McCarthy as a hero." In 1954, the Senate voted to censure McCarthy, and Kennedy drafted a speech supporting the censure. However, it was not delivered because Kennedy was hospitalized for back surgery in Boston. Although Kennedy never indicated how he would have voted, the episode damaged his support among members of the liberal community in the 1956 and 1960 elections.

In 1958, Kennedy was re-elected to the Senate, defeating his Republican opponent, Boston lawyer Vincent J. Celeste, with 73.6 percent of the vote, the largest winning margin in the history of Massachusetts politics. In the aftermath of his re-election, Kennedy began preparing to run for president by traveling throughout the U.S. with the aim of building his candidacy for 1960.

Most historians and political scientists who have written about Kennedy refer to his U.S. Senate years as an interlude. "His Senate career," concludes historian Robert Dallek, "produced no major legislation that contributed substantially to the national well-being." According to biographer Robert Caro, Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson viewed Kennedy as a "playboy", describing his performance in the Senate as "pathetic." Author John T. Shaw acknowledges that while his Senate career is not associated with acts of "historic statesmanship" or "novel political thought," Kennedy made modest contributions as a legislator, drafting more than 300 bills to assist Massachusetts and the New England region (some of which became law).

1960 presidential election

Main article: John F. Kennedy 1960 presidential campaign See also: 1960 Democratic Party presidential primaries and 1960 United States presidential election

On January 2, 1960, Kennedy announced his candidacy for the Democratic presidential nomination. Though some questioned Kennedy's age and experience, his charisma and eloquence earned him numerous supporters. Kennedy faced several potential challengers, including Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson, Adlai Stevenson II, and Senator Hubert Humphrey.

Kennedy traveled extensively to build his support. His campaign strategy was to win several primaries to demonstrate his electability to the party bosses, who controlled most of the delegates, and to prove to his detractors that a Catholic could win popular support. Victories over Senator Humphrey in the Wisconsin and West Virginia primaries gave Kennedy momentum as he moved on to the 1960 Democratic National Convention.

When Kennedy entered the convention, he had the most delegates, but not enough to ensure that he would win the nomination. Stevenson—the 1952 and 1956 presidential nominee—remained very popular, while Johnson also hoped to win the nomination with support from party leaders. Kennedy's candidacy also faced opposition from former President Harry S. Truman, who was concerned about Kennedy's lack of experience. Kennedy knew that a second ballot could give the nomination to Johnson or someone else, and his well-organized campaign was able to earn the support of just enough delegates to win the presidential nomination on the first ballot.

Kennedy ignored the opposition of his brother Robert, who wanted him to choose labor leader Walter Reuther, and other liberal supporters when he chose Johnson as his vice-presidential nominee. He believed that the Texas senator could help him win support from the South. In accepting the presidential nomination, Kennedy gave his well-known "New Frontier" speech:

For the problems are not all solved and the battles are not all won—and we stand today on the edge of a New Frontier. ... But the New Frontier of which I speak is not a set of promises—it is a set of challenges. It sums up not what I intend to offer the American people, but what I intend to ask of them.

At the start of the fall general election campaign, the Republican nominee and incumbent Vice President Richard Nixon held a six-point lead in the polls. Major issues included how to get the economy moving again, Kennedy's Catholicism, the Cuban Revolution, and whether the space and missile programs of the Soviet Union had surpassed those of the U.S. To address fears that his being Catholic would impact his decision-making, he told the Greater Houston Ministerial Association on September 12: "I am not the Catholic candidate for president. I am the Democratic Party candidate for president who also happens to be a Catholic. I do not speak for my Church on public matters—and the Church does not speak for me." He promised to respect the separation of church and state, and not to allow Catholic officials to dictate public policy.

The Kennedy and Nixon campaigns agreed to a series of televised debates. An estimated 70 million Americans, about two-thirds of the electorate, watched the first debate on September 26. Kennedy had met the day before with the producer to discuss the set design and camera placement. Nixon, just out of the hospital after a painful knee injury, did not take advantage of this opportunity and during the debate looked at the reporters asking questions and not at the camera. Kennedy wore a blue suit and shirt to cut down on glare and appeared sharply focused against the gray studio background. Nixon wore a light-colored suit that blended into the gray background; in combination with the harsh studio lighting that left Nixon perspiring, he offered a less-than-commanding presence. By contrast, Kennedy appeared relaxed, tanned, and telegenic, looking into the camera whilst answering questions. It is often claimed that television viewers overwhelmingly believed Kennedy, appearing to be the more attractive of the two, had won, while radio listeners (a smaller audience) thought Nixon had defeated him. However, only one poll split TV and radio voters like this and the methodology was poor. Pollster Elmo Roper concluded that the debates raised interest, boosted turnout, and gave Kennedy an extra two million votes, mostly as a result of the first debate. The debates are now considered a milestone in American political history—the point at which the medium of television began to play a dominant role.

Kennedy's campaign gained momentum after the first debate, and he pulled slightly ahead of Nixon in most polls. On Election Day, Kennedy defeated Nixon in one of the closest presidential elections of the 20th century. In the national popular vote, by most accounts, Kennedy led Nixon by just two-tenths of one percent (49.7% to 49.5%), while in the Electoral College, he won 303 votes to Nixon's 219 (269 were needed to win). Fourteen electors from Mississippi and Alabama refused to support Kennedy because of his support for the civil rights movement; they voted for Senator Harry F. Byrd of Virginia, as did an elector from Oklahoma. Forty-three years old, Kennedy was the youngest person ever elected to the presidency (though Theodore Roosevelt was a year younger when he succeeded to the presidency after the assassination of William McKinley in 1901).

Presidency (1961–1963)

Main article: Presidency of John F. Kennedy For a chronological guide, see Timeline of the John F. Kennedy presidency.

Kennedy was sworn in as the 35th president at noon on January 20, 1961. In his inaugural address, he spoke of the need for all Americans to be active citizens: "Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country." He asked the nations of the world to join to fight what he called the "common enemies of man: tyranny, poverty, disease, and war itself." He added:

All this will not be finished in the first one hundred days. Nor will it be finished in the first one thousand days, nor in the life of this Administration, nor even perhaps in our lifetime on this planet. But let us begin." In closing, he expanded on his desire for greater internationalism: "Finally, whether you are citizens of America or citizens of the world, ask of us here the same high standards of strength and sacrifice which we ask of you.

The address reflected Kennedy's confidence that his administration would chart a historically significant course in both domestic policy and foreign affairs. The contrast between this optimistic vision and the pressures of managing daily political realities would be one of the main tensions of the early years of his administration.

Kennedy scrapped the decision-making structure of Eisenhower, preferring an organizational structure of a wheel with all the spokes leading to the president; he was willing to make the increased number of quick decisions required in such an environment. Though the cabinet remained important, Kennedy generally relied more on his staffers within the Executive Office. In spite of concerns over nepotism, Kennedy's father insisted that Robert Kennedy become U.S. Attorney General, and the younger Kennedy became the "assistant president" who advised on all major issues.

Foreign policy

Main article: Foreign policy of the John F. Kennedy administration

Cold War and flexible response