| Revision as of 14:00, 25 May 2007 view sourceVaughan (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users3,287 edits →Substance use: add ref← Previous edit | Revision as of 14:10, 25 May 2007 view source MarkWood (talk | contribs)283 edits →Alternative approaches: chg to past tenseNext edit → | ||

| Line 207: | Line 207: | ||

| An approach broadly known as the ] movement, notably most active in the 1960s, has opposed the orthodox medical view of schizophrenia as an illness. | An approach broadly known as the ] movement, notably most active in the 1960s, has opposed the orthodox medical view of schizophrenia as an illness. | ||

| Psychiatrist ] |

Psychiatrist ] argued that psychiatric patients are not ill but are just individuals with unconventional thoughts and behavior that make society uncomfortable. He argues that society unjustly seeks to control such individuals by classifying their behavior as an illness and forcibly treating them as a method of ]. According to this view, "schizophrenia" does not actually exist but is merely a form of ], created by society's concept of what constitutes normality and abnormality. It is worth noting that Szasz has never considered himself to be "anti-psychiatry" in the sense of being against psychiatric treatment, but simply believes that it should be conducted between consenting adults, rather than imposed upon anyone against his or her will. | ||

| Similarly, psychiatrists ], ], ] and presently ]<ref> {{cite book | last = Colin | first = Ross | title = Schizophrenia: Innovations in Diagnosis and Treatment | publisher = Haworth Press | Similarly, psychiatrists ], ], ] and presently ]<ref> {{cite book | last = Colin | first = Ross | title = Schizophrenia: Innovations in Diagnosis and Treatment | publisher = Haworth Press | ||

| Line 214: | Line 214: | ||

| In the 1976 book '']'', psychologist ] proposed that until the beginning of historic times, schizophrenia or a similar condition was the normal state of human consciousness. This would take the form of a "]" where a normal state of low affect, suitable for routine activities, would be interrupted in moments of crisis by "mysterious voices" giving instructions, which early people characterized as interventions from the gods. This theory was briefly controversial. Continuing research has failed to either further confirm or refute the thesis. | In the 1976 book '']'', psychologist ] proposed that until the beginning of historic times, schizophrenia or a similar condition was the normal state of human consciousness. This would take the form of a "]" where a normal state of low affect, suitable for routine activities, would be interrupted in moments of crisis by "mysterious voices" giving instructions, which early people characterized as interventions from the gods. This theory was briefly controversial. Continuing research has failed to either further confirm or refute the thesis. | ||

| Psychiatrist ] |

Psychiatrist ] argued in a 1997 paper that schizophrenia may be the evolutionary price we pay for a left brain hemisphere specialization for ].<ref name="fn_56">Crow TJ (1997). Schizophrenia as failure of hemispheric dominance for language. ''Trends in Neurosciences'', 20(8), 339–343. PMID 9246721</ref> Since psychosis is associated with greater levels of right brain hemisphere activation and a reduction in the usual left brain hemisphere dominance, our language abilities may have evolved at the cost of causing schizophrenia when this system breaks down. | ||

| Researchers into ]ism have speculated that in some cultures schizophrenia or related conditions may predispose an individual to becoming a shaman.<ref name="fn_57">Polimeni J, Reiss JP (2002). How shamanism and group selection may reveal the origins of schizophrenia. ''Medical Hypothesis'', 58(3), 244–8. PMID 12018978</ref> Certainly, the experience of having access to multiple realities is not uncommon in schizophrenia, and is a core experience in many shamanic traditions. Equally, the shaman may have the skill to bring on and direct some of the ] psychiatrists label as illness. ], on the other hand, accept the psychiatric diagnoses. However, unlike the current ] they argue that ] causes the shaman’s schizoid personalities.<ref>], "The seven stages of historical personality" in ''The Emotional Life of Nations'' (Karnac, 2002). Available at Retrieved on ].</ref> Speculations regarding primary and important religious figures as having schizophrenia abound. Commentators such as ] and others have endorsed the idea that major religious figures experienced psychosis, heard voices and displayed delusions of grandeur.<ref>] (1986). ''The Transcendental Temptation: A Critique of Religion and the Paranormal'' (]) ISBN 0-87975-645-4</ref> | Researchers into ]ism have speculated that in some cultures schizophrenia or related conditions may predispose an individual to becoming a shaman.<ref name="fn_57">Polimeni J, Reiss JP (2002). How shamanism and group selection may reveal the origins of schizophrenia. ''Medical Hypothesis'', 58(3), 244–8. PMID 12018978</ref> Certainly, the experience of having access to multiple realities is not uncommon in schizophrenia, and is a core experience in many shamanic traditions. Equally, the shaman may have the skill to bring on and direct some of the ] psychiatrists label as illness. ], on the other hand, accept the psychiatric diagnoses. However, unlike the current ] they argue that ] causes the shaman’s schizoid personalities.<ref>], "The seven stages of historical personality" in ''The Emotional Life of Nations'' (Karnac, 2002). Available at Retrieved on ].</ref> Speculations regarding primary and important religious figures as having schizophrenia abound. Commentators such as ] and others have endorsed the idea that major religious figures experienced psychosis, heard voices and displayed delusions of grandeur.<ref>] (1986). ''The Transcendental Temptation: A Critique of Religion and the Paranormal'' (]) ISBN 0-87975-645-4</ref> | ||

Revision as of 14:10, 25 May 2007

Medical condition| Schizophrenia | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology |

Schizophrenia (from the Greek word σχιζοφρένεια, or schizophreneia, meaning "split mind") is a psychiatric diagnosis that describes a mental disorder characterized by impairments in the perception or expression of reality, most commonly manifest as auditory hallucinations and paranoid or bizarre delusions, and by significant social or occupational dysfunction. Onset of symptoms typically occurs in young adulthood, with a 0-5-1% of the population affected.

In 1893 psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin was the first to draw a distinction between what he termed dementia praecox and other psychotic illnesses. In 1908, psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler coined the term "schizophrenia", as he confirmed the disorder was not a form of dementia.

Although the disorder is primarily thought to affect cognition, it also usually contributes to chronic problems with behavior and emotion. Due to the many possible combinations of symptoms, heated debates are ongoing about whether the diagnosis necessarily or adequately describes one disorder, or represents a number of disorders. For this reason, Eugen Bleuler deliberately called the disease "the schizophrenias" (plural) when he coined the present name. Despite its etymology, "schizophrenia" is not synonymous with dissociative identity disorder, previously known as multiple personality disorder or "split personality"; in popular culture the two are often confused.

Diagnosis is based on the self-reported experiences of the patient, in combination with secondary signs observed by a psychiatrist, clinical psychologist or other clinician. No laboratory test for schizophrenia exists. Studies suggest that genetics, early environment, neurobiology and psychological and social processes are important contributory factors. Current psychiatric research into the development of the disorder often focuses on the role of neurobiology, although a reliable and identifiable organic cause has not been found. In the absence of a confirmed specific pathology underlying the diagnosis, some question the legitimacy of schizophrenia's status as a disease. Furthermore, some propose that the perceptions and feelings involved are meaningful and do not necessarily involve impairment.

Patients diagnosed with schizophrenia are highly likely to be diagnosed with other disorders. The lifetime prevalence of substance abuse is typically around 40%. Comorbidity is also high with clinical depression, anxiety disorders, and social problems, and a generally decreased life expectancy is also present. Patients diagnosed with schizophrenia typically live ten to twelve years less than those without the disorder, owing to increased physical health problems and a high suicide rate. Unemployment and poverty are common.

History

The term "schizophrenia" translates roughly as "splitting of the mind", and comes from the Greek σχίζω (or schizo, "to split" or "to divide") and φρήν (or phrēn, "mind"). Accounts that may relate to symptoms of schizophrenia date back as far as 2000 BC in the Book of Hearts, part of the ancient Ebers papyrus. However, a recent study into the ancient Greek and Roman literature showed that although the general population probably had an awareness of psychotic disorders, there was no recorded condition that would meet the modern criteria for schizophrenia.

This broad concept of "madness" has existed for thousands of years, but schizophrenia was only classified as a distinct mental disorder by Emil Kraepelin in 1893. He was the first to make a distinction in the psychotic disorders between what he called dementia praecox (a term first used by psychiatrist Bénédict Morel 1809–1873) and manic depression. Kraepelin believed that dementia praecox was primarily a disease of the brain, and particularly a form of dementia. Kraepelin named the disorder 'dementia praecox' (early dementia) to distinguish it from other forms of dementia, such as Alzheimer's disease, which occur late in life.

The word "schizophrenia" was coined by Eugene Bleuler in 1908 to refer to the lack of interaction between thought processes and perception. Bleuler described the main symptoms as 4 "A"'s: flattened Affect, Autism, impaired Association of ideas and Ambivalence. Bleuler realized that the illness was not a dementia as some of his patients improved rather than deteriorated and hence proposed the term schizophrenia instead.

With the name "schizophrenia" Bleuler intended to capture the separation of function between personality, thinking, memory, and perception. The term, however, is commonly misunderstood to mean that affected persons have a "split personality". Although some people diagnosed with schizophrenia may hear voices and may experience the voices as distinct personalities, schizophrenia does not involve a person changing among distinct multiple personalities. The confusion perhaps arises in part due to the meaning of Bleuler's term 'schizophrenia' (literally 'split' or 'shattered mind'). The first known misuse of "schizophrenia" to mean "split personality" was in an article by the poet T. S. Eliot in 1933.

In the first half of the twentieth century schizophrenia was considered by many to be a "hereditary defect", and individuals affected by schizophrenia became subject to eugenics in many countries. Hundreds of thousands were sterilized, with or without consent, the majority in Nazi Germany, the United States, and Scandinavian countries, Many people diagnosed with schizophrenia, together with other people labeled "mentally unfit", were murdered in the Nazi "Operation T-4" program.

Signs and symptoms

A person experiencing schizophrenia is typically characterized as demonstrating disorganized thinking, and as experiencing delusions or hallucinations, in particular auditory hallucinations. Onset of schizophrenia typically occurs in late adolescence or early adulthood, with males tending to show symptoms earlier than females. No one symptom is diagnostic of schizophrenia, and all can occur in various other medical or psychiatric conditions.

Some symptoms, such as social isolation, may be caused by a number of factors. One possible factor is impairment in social cognition, which is associated with schizophrenia, but isolation may also result from an individual reacting to psychotic symptoms (such as paranoia) or avoiding potentially stressful social situations which may exacerbate mental distress in some people.

Much work in recent years has gone into the prodromal (pre-onset) phase of the illness; many people later diagnosed with schizophrenia experience difficulties including nonspecific symptoms of social withdrawal, irritability and dysphoria as well as transient or self-limiting psychotic symptoms

Schneiderian classification

The psychiatrist Kurt Schneider attempted to list the particular forms of psychotic symptoms that he thought were particularly useful in distinguishing between schizophrenia and other disorders that could produce psychosis. These are called first rank symptoms or Schneiderian first rank symptoms and include delusions of being controlled by an external force, the belief that thoughts are being inserted into or withdrawn from one's conscious mind, the belief that one's thoughts are being broadcast to other people and hearing hallucinatory voices which comment on one's thoughts or actions, or may have a conversation with other hallucinated voices. The reliability of 'first rank symptoms' has been questioned, although they have contributed to the current DSM IV-TR diagnostic criteria used in many countries.

Positive and negative symptoms

Schizophrenia is often described in terms of "positive" (or productive) and "negative" (or deficit) symptoms. Positive symptoms include delusions, auditory hallucinations and thought disorder and are typically regarded as manifestations of psychosis. Negative symptoms are so named because they are considered to be the loss or absence of normal traits or abilities, and include features such as flat, blunted or constricted affect and emotion, poverty of speech and lack of motivation. Additionally, a 'disorganization syndrome' and neurocognitive deficits may be present. These may take the form of reduced or impaired psychological functions such as memory, attention, problem-solving, executive function or social cognition. A third symptom grouping, the so-called 'disorganization syndrome', includes disorganized speech (thought disorder) and related disorganized behavior.

Diagnosis

The diagnostic category of schizophrenia has been widely criticised as lacking in scientific validity or reliability, consistent with evidence of poor levels of consistency in diagnostic practices and the use of criteria. One alternative suggests that the problems and issues making up the diagnosis of schizophrenia would be better addressed as individual dimensions along which everyone varies, such that there is a spectrum or continuum rather than a cut-off between normal and ill. This approach appears consistent with research on schizotypy and of a relatively high prevalence of psychotic experiences and delusional beliefs amongst the general public. Like many mental illnesses, the diagnosis of schizophrenia is based upon the behavior of the person being assessed. There is a list of criteria that must be met for someone to be so diagnosed. These depend on both the presence and duration of certain signs and symptoms.

DSM IV-TR Criteria

The most commonly used criteria for diagnosing schizophrenia are from the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and the World Health Organization's International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD).

To be diagnosed as having schizophrenia, a person must display:

- Characteristic symptoms: Two or more of the following, each present for a significant portion of time during a one-month period (or less, if successfully treated)

- delusions

- hallucinations

- disorganized speech (e.g., frequent derailment or incoherence; speaking in abstracts). See thought disorder.

- grossly disorganized behavior (e.g. dressing inappropriately, crying frequently) or catatonic behavior

- negative symptoms, i.e., affective flattening (lack or decline in emotional response), alogia (lack or decline in speech), or avolition (lack or decline in motivation).

- Note: Only one of these symptoms is required if delusions are bizarre or hallucinations consist of hearing one voice participating in a running commentary of the patient's actions or of hearing two or more voices conversing with each other.

- Social/occupational dysfunction: For a significant portion of the time since the onset of the disturbance, one or more major areas of functioning such as work, interpersonal relations, or self-care, are markedly below the level achieved prior to the onset.

- Duration: Continuous signs of the disturbance persist for at least six months. This six-month period must include at least one month of symptoms (or less, if successfully treated).

Additional criteria are also given that exclude a diagnosis of schizophrenia if symptoms of mood disorder or pervasive developmental disorder are present. Additionally a diagnosis of schizophrenia is excluded if the symptoms are the direct result of a substance (e.g., abuse of a drug, medication) or a general medical condition.

Subtypes

Historically, schizophrenia in the West was classified into simple, catatonic, hebephrenic, and paranoid. The DSM now contains five sub-classifications of schizophrenia, the ICD-10 identifies 7:

- (295.2/F20.2) catatonic type (prominent psychomotor disturbances are evident. Symptoms can include catatonic stupor and waxy flexibility).

- (295.1/F20.1) disorganized type (where thought disorder and flat affect are present together),

- (295.3/F20.0) paranoid type (where delusions and hallucinations are present but thought disorder, disorganized behavior, and affective flattening are absent),

- (295.6/F20.5) residual type (where positive symptoms are present at a low intensity only) and

- (295.9/F20.3) undifferentiated type (psychotic symptoms are present but the criteria for paranoid, disorganized, or catatonic types have not been met).

NB: Brackets indicate codes for DSM and ICD-10 diagnostic manuals, respectively. Some older classifications still use "Hebephrenic schizophrenia" instead of "Disorganized schizophrenia".

Diagnostic issues and controversies

It has been argued that the diagnostic approach to schizophrenia is flawed, as it relies on an assumption of a clear dividing line between what is considered to be mental illness (fulfilling the diagnostic criteria) and mental health (not fulfilling the criteria). Recently it has been argued, notably by psychiatrist Jim van Os and psychologist Richard Bentall, that this makes little sense, as studies have shown that many people have psychotic experiences and have delusion-like ideas without becoming distressed, disabled or diagnosable by the categorical system (potentially because they interpret their experiences in more positive ways, or hold more pragmatic and commonly accepted beliefs).

Of particular concern is that the decision as to whether a symptom is present is a subjective decision by the person making the diagnosis or relies on an incoherent definition (for example, see the entries on delusions and thought disorder for a discussion of this issue). More recently, it has been argued that psychotic symptoms are not a good basis for making a diagnosis of schizophrenia as "psychosis is the 'fever' of mental illness — a serious but nonspecific indicator".

Perhaps because of these factors, studies examining the diagnosis of schizophrenia have typically shown relatively low or inconsistent levels of diagnostic reliability. Most famously, David Rosenhan's 1972 study, published as On being sane in insane places, demonstrated that the diagnosis of schizophrenia was (at least at the time) often subjective and unreliable. More recent studies have found agreement between any two psychiatrists when diagnosing schizophrenia tends to reach about 65% at best. This, and the results of earlier studies of diagnostic reliability (which typically reported even lower levels of agreement) have led some critics to argue that the diagnosis of schizophrenia should be abandoned.

In 2004 in Japan, Japanese term of schizophrenia was changed from Seishin-Bunretsu-Byo (mind-split-disease) to Tōgō-shitchō-shō (integration disorder). In 2006, campaigners in the UK, under the banner of Campaign for Abolition of the Schizophrenia Label, argued for a similar rejection of the diagnosis of schizophrenia and a different approach to the treatment and understanding of the symptoms currently associated with it.

Alternatively, other proponents have argued for a new approach that would use the presence of specific neurocognitive deficits to make a diagnosis. These often accompany schizophrenia and take the form of a reduction or impairment in basic psychological functions such as memory, attention, executive function and problem solving. It is these sorts of difficulties, rather than the psychotic symptoms (which can in many cases be controlled by antipsychotic medication), which seem to be the cause of most disability in schizophrenia. However, this argument is relatively new and it is unlikely that the method of diagnosing schizophrenia will change radically in the near future.

The diagnostic approach to schizophrenia has also been opposed by the proponents of the anti-psychiatry movement, who argue that classifying specific thoughts and behaviors as an illness allows social control of people that society finds undesirable but who have committed no crime. They argue that this is a way of unjustly classifying a social problem as a medical one to allow the forcible detention and treatment of people displaying these behaviors, which is something which can be done under mental health legislation in most Western countries.

An example of this can be seen in the Soviet Union, where an additional sub-classification of sluggishly progressing schizophrenia was created. Particularly in the RSFSR (Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic), this diagnosis was used for the purpose of silencing political dissidents or forcing them to recant their ideas by the use of forcible confinement and treatment. In 2000 similar concerns about the abuse of psychiatry to unjustly silence and detain practitioners of the Falun Gong movement by the Chinese government led the American Psychiatric Association's Committee on the Abuse of Psychiatry and Psychiatrists to pass a resolution to urge the World Psychiatric Association to investigate the situation in China.

Western psychiatric medicine tends to favor a definition of symptoms that depends on form rather than content (an innovation first argued for by psychiatrists Karl Jaspers and Kurt Schneider). Therefore, a subject should be able to believe anything, however unusual or socially unacceptable, without being diagnosed delusional, unless their belief is held in a particular way. In principle, this would stop people being forcibly detained or treated simply for what they believe. However, the distinction between form and content is not easy, or always possible, to make in practice (see delusion). This had led to accusations by anti-psychiatry, surrealist and mental health system survivor groups that psychiatric abuses exist in the West as well.

Epidemiology

In the western world, schizophrenia is typically diagnosed in late adolescence or early adulthood. It is found approximately equally in men and women in western cultures, though its onset is later on average in women, who tend to experience a better course and outcome. Relatively rare are instances of childhood-onset schizophrenia and late-onset schizophrenia (occurring in old age). The lifetime prevalence of schizophrenia—that is, the proportion of individuals expected to experience the disease at any time in their lives—is commonly given at 1%. A 2002 systematic review of many studies, however, found a lifetime prevalence of 0.55%. The same study found that prevalence may vary greatly among countries, despite the received wisdom that schizophrenia occurs at similar rates throughout the world. Due to this high, although variable incidence, schizophrenia is a major cause of disability. In a 1999 study of 14 countries, active psychosis was ranked the third-most-disabling condition, after quadriplegia and dementia and before paraplegia and blindness.

One particularly stable and replicable finding, often referred to as Urban Drift, has been the association between living in an urban environment and schizophrenia diagnosis, even after factors such as drug use, ethnic group and size of social group have been controlled for.

Causes

Main article: Causes of schizophrenia

While the reliability of the diagnosis introduces difficulties in measuring the relative effect of genes and environment (for example, symptoms overlap to some extent with severe bipolar disorder or major depression), evidence suggests that genetic vulnerability and environmental stressors can act in combination to result in onset of schizophrenia. However, the proportion of these factors' influence is widely and heatedly debated.

The idea of an inherent vulnerability (or diathesis) in some people which can be unmasked by a biological, psychological or environmental stressor is known as the Stress-diathesis model. Evidence suggests that the diagnosis of schizophrenia has a significant heritable component, although this may be significantly influenced by subsequent environmental factors or stressors which trigger or cause illness onset. As an example, monozygotic twins, who have identical genetic material, have a 50% chance of concordance.

Childhood experiences of abuse or trauma have also been implicated as risk factors for a diagnosis of schizophrenia later in life.

Genetic

Schizophrenia is likely to be a diagnosis of complex inheritance. Thus, it is likely that several genes interact to generate risk for schizophrenia or for the separate components that can co-occur to lead to a diagnosis. This, combined with disagreements over which research methods are best, or how data from genetic research should be interpreted, has led to differing estimates over genetic contribution.

There is a great deal of effort being put into molecular genetic studies of schizophrenia, which attempt to identify specific genes which may increase risk. Because of this, the genes that are thought to be most involved can change as new evidence is gathered.

Prenatal

It is thought that causal factors can initially come together in early neurodevelopment, including during pregnancy, to increase the risk of later developing schizophrenia. One curious finding is that people diagnosed with schizophrenia are more likely to have been born in winter or spring, (at least in the northern hemisphere). There is now significant evidence that prenatal exposure to infections increases the risk for developing schizophrenia later in life, providing additional evidence for a link between in utero developmental pathology and risk of developing the condition.

Substance use

The relationship between schizophrenia and drug use is complex, meaning that a clear causal connection between drug use and schizophrenia has been difficult to tease apart. There is strong evidence that using certain drugs can trigger either the onset or relapse of schizophrenia in some people. It may also be the case, however, that people with schizophrenia use drugs to overcome negative feelings associated with both the commonly prescribed antipsychotic medication and the condition itself, where negative emotion, paranoia and anhedonia are all considered to be core features.

Amphetamines trigger the release of dopamine and excessive dopamine function is believed to be responsible for many symptoms of schizophrenia (known as the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia), amphetamines may worsen schizophrenia symptoms. Schizophrenia can sometimes be triggered by heavy use of hallucinogenic or stimulant drugs. There is evidence that cannabis use can contribute to schizophrenia.

People with schizophrenia tend to smoke significantly more tobacco than the general population. Despite the higher prevalence of tobacco smoking, people diagnosed with schizophrenia have a much lower than average chance of developing and dying from lung cancer. While the reason for this is unknown, it may be because of a genetic resistance to the cancer, a side-effect of drugs being taken, or a statistical effect of increased likelihood of dying from causes other than lung cancer. A recent study of over 50,000 Swedish conscripts found that there was a small but significant protective effect of smoking cigarettes on the risk of developing schizophrenia later in life. The increased rate of smoking in schizophrenia may be due to a desire to self-medicate with nicotine. One possible reason is that smoking produces a short term effect to improve alertness and cognitive functioning in persons who suffer this illness. It has been postulated that the mechanism of this effect is that people with schizophrenia have a disturbance of nicotinic receptor functioning which is temporarily abated by tobacco use.

Pathophysiology

Differences in the size and structure of certain brain areas have been found in some adults diagnosed with schizophrenia. Early findings came from the discovery of ventricular enlargement in people diagnosed with schizophrenia with negative symptoms most prominent. However, this finding has not proved particularly reliable on the level of the individual person, with considerable variation between patients. More recent studies have shown a large number of differences in brain structure between people with and without diagnoses of schizophrenia. However, as with earlier studies, many of these differences are only reliably detected when comparing groups of people, and are unlikely to predict any differences in brain structure of an individual person with schizophrenia.

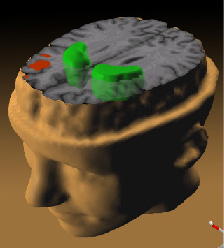

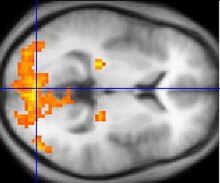

Studies using neuropsychological tests and brain imaging technologies such as fMRI and PET to examine functional differences in brain activity have shown that differences seem to most commonly occur in the frontal lobes, hippocampus, and temporal lobes. These differences are heavily linked to the neurocognitive deficit often asssociated with schizophrenia, particularly in areas of memory, attention, problem solving, executive function, and social cognition.

Electroencephalograph (EEG) recordings of persons with schizophrenia performing perception oriented tasks showed an absence of gamma band activity in the brain, indicating weak integration of critical neural networks in the brain. Those who experienced intense hallucinations, delusions and disorganized thinking showed the lowest frequency synchronization. None of the drugs taken by the persons scanned had moved neural synchrony back into the gamma frequency range. Gamma band and working memory alterations may be related to alterations in interneurons that produced the neurotransmitter GABA.

Dopamine

Main article: Dopamine hypothesis of schizophreniaParticular focus has been placed upon the function of dopamine in the mesolimbic pathway of the brain. This focus largely resulted from the accidental finding that a drug group which blocks dopamine function, known as the phenothiazines, could reduce psychotic symptoms. An influential theory, known as the "dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia", proposed that a malfunction involving dopamine pathways was therefore the cause of (the positive symptoms of) schizophrenia. This theory is now thought to be overly simplistic as a complete explanation, partly because newer antipsychotic medication (called atypical antipsychotic medication) can be equally effective as older medication (called typical antipsychotic medication), but also affects serotonin function and may have slightly less of a dopamine blocking effect. In addition dopamine pathway dysfunction has not been reliably shown to correlate with symptom onset or severity.

Glutamate

Interest has also focused on the neurotransmitter glutamate and the reduced function of the NMDA glutamate receptor in schizophrenia. This has largely been suggested by abnormally low levels of glutamate receptors found in postmortem brains of people previously diagnosed with schizophrenia and the discovery that the glutamate blocking drugs such as phencyclidine and ketamine can mimic the symptoms and cognitive problems associated with the condition. The fact that reduced glutamate function is linked to poor performance on tests requiring frontal lobe and hippocampal function and that glutamate can affect dopamine function, all of which have been implicated in schizophrenia, have suggested an important mediating (and possibly causal) role of glutamate pathways in schizophrenia. Further support of this theory has come from preliminary trials suggesting the efficacy of coagonists at the NMDA receptor complex in reducing some of the positive symptoms of schizophrenia.

Treatment and services

The concept of a "cure" remains controversial, as there is no consensus on the definition. Some criteria for the remission of symptoms have recently been suggested. The effectiveness of schizophrenia treatment is often assessed using standardized methods, one of the most common being the positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS). As with many chronic illness, aiming for management of symptoms and improving function is more achievable than a "cure".

Medication

The mainstay of treatment for schizophrenia is an antipsychotic medication. These are thought to provide symptomatic relief from the positive symptoms of psychosis. The newer atypical antipsychotic drugs are usually preferred for initial treatment over the older typical antipsychotics. The atypicals are associated with lower rates of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and tardive dyskinesia, although they are more likely to induce weight gain and obesity-related diseases. It remains unclear whether the newer antipsychotics reduce the chances of developing neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a neurological disorder most often caused by an adverse reaction to neuroleptic or antipsychotic drugs.

The two classes of antipsychotics are generally thought equally effective for the treatment of the positive symptoms. Some researchers have suggested that the atypicals offer additional benefit for the negative symptoms and cognitive deficits associated with schizophrenia, although the clinical significance of these effects has yet to be established. Recent reviews have suggested that typical antipsychotics, when dosed conservatively, have effects similar to atypicals. The atypical antipsychotics are much more expensive for consumers, and profitable for drug companies, because they remain protected by patents. Older drugs are now available in inexpensive generic equivalents.

A novel approach to medication is the use of omega-3 fatty acids, which are found in foods such as oily fish, flax seeds, hemp seeds, walnuts and canola oil) have recently been studied as a treatment for schizophrenia. Although the number of research trials has been limited, the majority of randomized controlled trials have found omega-3 supplements to be effective when used as a dietary supplement.

Psychological and social interventions

Psychotherapy may be used in the treatment of schizophrenia. It has been reported that, despite evidence and recommendations, treatment is often confined to pharmacotherapy alone because of reimbursement problems or lack of training. Electroconvulsive therapy (also known as 'electroshock') may be used in countries where it is legal. It is not considered a first line treatment but may be prescribed in cases where other treatments have failed. Psychosurgery has now become a rare procedure and is not a recommended treatment for schizophrenia. Therapy which addresses the whole family system of an individual with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, including through psychological education, has also been found to have significant benefits.

Cognitive behavioral therapy may focus on the direct reduction of the symptoms, or on related aspects, such as issues of self-esteem, social functioning, and insight. Although the results of early trials with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) were inconclusive, more recent reviews suggest that CBT can be an effective treatment for the psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia. There have also been advances in social skills training.

Another approach is cognitive remediation therapy, a technique aimed at remediating the neurocognitive deficits sometimes present in schizophrenia. Based on techniques of neuropsychological rehabilitation, early evidence has shown it to be cognitively effective, with some improvements related to measurable changes in brain activation as measured by fMRI. A similar approach known as cognitive enhancement therapy, which focuses on social cognition as well as neurocognition, has shown efficacy. A recent randomised controlled trial found that music therapy significantly improved symptom scores in a group of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. A notable early mention of the beneficial effect of music on mental illness was in 1621 by Robert Burton in The Anatomy of Melancholy.

Community and inpatient services

Support services available can include drop-in centers, visits from members of a 'community mental health team' or Assertive Community Treatment team, supported employment and patient-led support groups.

In recent years the importance of service-user led recovery based movements has grown substantially throughout Europe and America. Groups such as the Hearing Voices Network and more recently, the Paranoia Network, have developed a self-help approach that aims to provide support and assistance outside of the traditional medical model adopted by mainstream psychiatry. By avoiding framing personal experience in terms of criteria for mental illness or mental health, they aim to destigmatize the experience and encourage individual responsibility and a positive self-image. Peer-to-peer support is also developing a professional footing with partnerships between hospitals and consumer run groups becoming more common. These services work towards remediating social withdrawal, building social skills and reducing rehospitalization.

In many non-Western societies, schizophrenia may only be treated with more informal, community-led methods. The outcome for people diagnosed with schizophrenia in non-Western countries may actually be better than for people in the West. The reasons for this effect are not clear, although cross-cultural studies are being conducted.

Hospitalization may occur, with severe episodes of schizophrenia. This can be voluntary or (if mental health legislation allows it) involuntary (called civil or involuntary commitment). Long-term inpatient stays are now less common due to deinstitutionalization, although can still occur.

Prognosis

One retrospective study has shown that about a third of people make a full recovery, about a third show improvement but not a full recovery, and a third remain ill. A more recent study using stricter recovery criteria (i.e. concurrent remission of positive and negative symptoms and specific instances of adequate social / vocational functioning) reported a recovery rate of 13.7%. However, the exact definition of what constitutes recovery has not been widely defined, although criteria have recently been suggested to define a remission in symptoms. Therefore, this makes it difficult to give an exact estimate as recovery and remission rates are not always comparable across studies.

The World Health Organization conducted two long-term follow-up studies involving more than 2,000 people suffering from schizophrenia in different countries. These studies' findings were that these patients have much better long-term outcomes in developing countries (India, Colombia and Nigeria) than in developed countries (USA, UK, Ireland, Denmark, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Japan, and Russia), despite the fact antipsychotic drugs are typically not widely available in poorer countries, thus raising questions about the effectiveness of such drug-based treatments.

Just as the clarity of the diagnosis itself attacts controversy and criticism, it is difficult to establish a clear picture of recovery and rehabilitation. Both long ago and in the recent past, patients in developed countries were told that chances of recovery were limited, with statistics being quoted to support this negative prognosis. Today, with the advent of a vocal "Recovery Movement" in mental health, and longitudinal studies indicating better rates of recovery than previously assumed, attention is drawn to cultural and local factors in impeding or accelerating recovery and different models of rehabilitation and recovery.

Factors

Several factors are associated with a better prognosis: Being female, acute (vs. insidious) onset of symptoms, older age of first episode, predominantly positive (rather than negative) symptoms, presence of mood symptoms and good premorbid functioning. Most studies done on this subject, however, are correlational in nature, and a clear cause-and-effect relationship is difficult to establish.

High EE

Evidence is also consistent that negative attitudes towards individuals with schizophrenia can have a significant adverse impact. In particular, critical comments, hostility, authoritarian and intrusive or controlling attitudes (termed 'high expressed emotion' by researchers) from family members have been found to correlate with a higher risk of relapse in schizophrenia across cultures.

Life Expectancy

In a study of over 168,000 Swedish citizens undergoing psychiatric treatment, schizophrenia was associated with an average life expectancy of approximately 80–85% of that of the general population. Women with a diagnosis of schizophrenia were found to have a slightly better life expectancy than that of men, and as a whole, a diagnosis of schizophrenia was associated with a better life expectancy than substance abuse, personality disorder, heart attack and stroke.

Suicide rate

There is an extremely high suicide rate associated with schizophrenia. A recent study showed that 30% of patients diagnosed with this condition had attempted suicide at least once during their lifetime. Another study suggested that 10% of persons with schizophrenia die by suicide.

Violence

The relationship between violent acts and the diagnosis of schizophrenia is a contentious topic. A national survey in the United States indicated that 61% of Americans judge individuals with schizophrenia as likely to commit an act of interpersonal violence, while 17% thought such an act would be committed by person described only as "troubled".

Research on violent acts indicates a moderately increased number of violent acts by a minority of individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. An assessment of violent acts verified by multiple sources indicated that 15% of individuals with schizophrenia had committed violent acts during the course of a year, which was statistically related to substance abuse, and to the relatively poor and violent neighbourhoods in which they resided. An assessment of individuals enrolled in a trial of antipsychotic medication indicated that 19% had committed violent acts in the preceding six months, with 15.5% being of a "minor" nature.

Population-attributable figures indicate that a small percentage (3% in the ECA study in America) of the overall violence of a given population is attributable to people with schizophrenia, and that the majority of this risk is attributable to substance misuse, young age, other correlated variables, and social and economic contexts, rather than schizophrenia per se. Studies suggest that 5–10% of those awaiting trial for murder in Western countries have a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, with lower figures for convictions, representing a tiny probability for a given individual with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. A consistent finding from this research is that individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia are often the victims of violent crime—at least 14 times more often than they are perpetrators, with 4.3% having been victims in a one-month period. This ongoing "victimization" has been linked to an increased perception of threat among people with schizophrenia, and to their commission of violent acts. Another consistent finding is a link to substance misuse, particularly alcohol, among the minority who commit violent acts.

The occurrence of psychosis in schizophrenia has also been linked to a higher risk of violent acts. Findings on the specific role of delusions or hallucinations are inconsistent, but have included a focus on delusional jealousy and perception of threat or command hallucinations. It has also been proposed that there is a type of individual with schizophrenia characterized by a history of educational difficulties, low IQ, conduct disorder, early-onset substance misuse and offending prior to diagnosis. Violence by or against individuals with schizophrenia typically occurs in the context of complex social interactions (including in atmosphere of mutually high "expressed emotion") within a family setting, as well as being an issue in healthcare settings and the wider community.

Alternative approaches

An approach broadly known as the anti-psychiatry movement, notably most active in the 1960s, has opposed the orthodox medical view of schizophrenia as an illness.

Psychiatrist Thomas Szasz argued that psychiatric patients are not ill but are just individuals with unconventional thoughts and behavior that make society uncomfortable. He argues that society unjustly seeks to control such individuals by classifying their behavior as an illness and forcibly treating them as a method of social control. According to this view, "schizophrenia" does not actually exist but is merely a form of social constructionism, created by society's concept of what constitutes normality and abnormality. It is worth noting that Szasz has never considered himself to be "anti-psychiatry" in the sense of being against psychiatric treatment, but simply believes that it should be conducted between consenting adults, rather than imposed upon anyone against his or her will.

Similarly, psychiatrists R. D. Laing, Silvano Arieti, Theodore Lidz and presently Colin Ross have argued that the symptoms of what is normally called mental illness are comprehensible reactions to impossible demands that society and particularly family life places on some sensitive individuals. Laing, Arieti, Lidz and Ross were revolutionary in valuing the content of psychotic experience as worthy of interpretation, rather than considering it simply as a secondary but essentially meaningless marker of underlying psychological or neurological distress. Laing's work, co-authored with Aaron Esterson, Sanity, Madness and the Family (1964) described eleven case studies of people diagnosed with schizophrenia and argued that the content of their actions and statements was meaningful and logical in the context of their family and life situations. Arieti's Interpretation of Schizophrenia won the 1975 scientific National Book Award in the United States. In the books Schizophrenia and the Family and The Origin and Treatment of Schizophrenic Disorders Lidz and his colleagues explain their belief that parental behaviour can result in mental illness in children.

In the 1976 book The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, psychologist Julian Jaynes proposed that until the beginning of historic times, schizophrenia or a similar condition was the normal state of human consciousness. This would take the form of a "bicameral mind" where a normal state of low affect, suitable for routine activities, would be interrupted in moments of crisis by "mysterious voices" giving instructions, which early people characterized as interventions from the gods. This theory was briefly controversial. Continuing research has failed to either further confirm or refute the thesis.

Psychiatrist Tim Crow argued in a 1997 paper that schizophrenia may be the evolutionary price we pay for a left brain hemisphere specialization for language. Since psychosis is associated with greater levels of right brain hemisphere activation and a reduction in the usual left brain hemisphere dominance, our language abilities may have evolved at the cost of causing schizophrenia when this system breaks down.

Researchers into shamanism have speculated that in some cultures schizophrenia or related conditions may predispose an individual to becoming a shaman. Certainly, the experience of having access to multiple realities is not uncommon in schizophrenia, and is a core experience in many shamanic traditions. Equally, the shaman may have the skill to bring on and direct some of the altered states of consciousness psychiatrists label as illness. Psychohistorians, on the other hand, accept the psychiatric diagnoses. However, unlike the current medical model of mental disorders they argue that poor parenting in tribal societies causes the shaman’s schizoid personalities. Speculations regarding primary and important religious figures as having schizophrenia abound. Commentators such as Paul Kurtz and others have endorsed the idea that major religious figures experienced psychosis, heard voices and displayed delusions of grandeur.

Alternative medicine tends to hold the view that schizophrenia is primarily caused by imbalances in the body's reserves and absorption of dietary minerals, vitamins, fats, and/or the presence of excessive levels of toxic heavy metals. The body's adverse reactions to gluten are also strongly implicated in some alternative theories (see gluten-free, casein-free diet). Although this theory is generally deemed to be unproven, it is worth noting that it was positively discussed in the Lancet in 1970, the British Medical Journal in 1973, and other publications. A recent literature by scientists at Johns Hopkins University confirms some of these findings. The branch of alternative medicine that deals with these views regarding the cause of schizophrenia, is known as orthomolecular psychiatry. Hoffer and Walker, in their book Orthomolecular Nutrition (Keats Publishing, 1978), argue that schizophrenia can be treated effectively with doses of Vitamin B-3 (Niacin).

An additional approach is suggested by the work of Richard Bandler who argues that "The usual difference between someone who hallucinates and someone who visualizes normally, is that the person who hallucinates doesn't know he's doing it or doesn't have any choice about it." (Time for a Change, p107). He suggests that because visualization is a sophisticated mental capability, schizophrenia is a skill, albeit an involuntary and dysfunctional one that is being used but not controlled. He therefore suggests that a significant route to treating schizophrenia might be to teach the missing skill — how to distinguish created reality from consensus external reality, to reduce its maladaptive impact, and ultimately how to exercise appropriate control over the vizualization or auditory process. Hypnotic approaches have been explored by the physician Milton H. Erickson as a means of facilitating this.

Cultural references

The book and film A Beautiful Mind chronicled the life of John Forbes Nash, a Nobel-Prize-winning mathematician who was diagnosed with schizophrenia. The Marathi film Devrai (Featuring Atul Kulkarni) is a presentation of a patient with schizophrenia. The film, set in the Konkan region of Maharashtra in Western India, shows the behavior, mentality, and struggle of the patient as well as his loved-ones. It also portrays the treatment of this mental illness using medication, dedication and lots of patience of the close relatives of the patient.

In Bulgakov's Master and Margarita the poet Ivan Bezdomnyj is institutionalized and diagnosed with schizophrenia after witnessing the devil (Woland) predict Berlioz's death. The book The Eden Express by Mark Vonnegut accounts his struggle into schizophrenia and his journey back to sanity.

See also

|

|

Notes

- Liddell & Scott (1980). Greek-English Lexicon, Abridged Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- Evans, K., McGrath, J., & Milns, R. (2003). Searching for schizophrenia in ancient Greek and Roman literature: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandanavica, 107(5), 323–330. PMID 12752027

- Kraepelin, E. (1907) Text book of psychiatry (7th ed) (trans. A.R. Diefendorf). London: Macmillan.

- ^ "Conditions in Occupational Therapy: effect on occupational performance." ed. Ruth A. Hansen and Ben Atchison (Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Williams, 2000), 54–74. ISBN 0-683-30417-8

- Stotz-Ingenlath G. (2000). Epistemological aspects of Eugen Bleuler's conception of schizophrenia in 1911. Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy, 3(2), 153–9. PMID 11079343

- Turner, T. (1999) 'Schizophrenia'. In G.E. Berrios and R. Porter (eds) A History of Clinical Psychiatry. London: Athlone Press. ISBN 0-485-24211-7

- Allen GE. (1997). The social and economic origins of genetic determinism: a case history of the American Eugenics Movement, 1900–1940 and its lessons for today. Genetica, 99, 77–88. PMID 9463076

- Read, J., Masson, J. (2004) Genetics, eugenics and mass murder. In J. Read, L.R. Mosher, R.P. Bentall (eds) Models of Madness: Psychological, Social and Biological Approaches to Schizophrenia. ISBN 1-58391-906-6

- American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition TR Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- ^ Sadock & Sadock, p. 472

- ^ Sadock & Sadock, pp. 490–491.

- Freeman D, Garety PA, Kuipers E, Fowler D, Bebbington PE, Dunn G. (2007) Acting on persecutory delusions: the importance of safety seeking. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45 (1), 89-99. PMID 16530161

- Parnas J, Jorgensen A. (1989) Pre-morbid psychopathology in schizophrenia spectrum. British Journal of Psychiatry, 155, 623-7.

- Amminger GP, Leicester S, Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Berger GE, Francey SM, Yuen HP, McGorry PD. (2006) Early-onset of symptoms predicts conversion to non-affective psychosis in ultra-high risk individuals. Schizophrenia Research, 84 (1), 67-76. PMID 16677803

- Bertelsen, A. (2002). Schizophrenia and Related Disorders: Experience with Current Diagnostic Systems. Psychopathology, 35, 89–93. PMID 12145490

- BehaveNet® Clinical Capsule™: DSM-IV & DSM-IV-TR, Schizophrenia. Behavenet.com, Retrieved on 2007-05-17.

- Verdoux, H., & van Os, J. (2002). Psychotic symptoms in non-clinical populations and the continuum of psychosis. Schizophrenia Research, 54(1–2), 59–65. PMID 11853979

- LC, van Os J. (2001). The continuity of psychotic experiences in the general population. Clinical Psychology Review, 21 (8),1125–41. PMID 11702510

- E.R. Peters, S. Day, J. McKenna, G. Orbach (2005). Measuring delusional ideation: the 21-item Peters et al. Delusions Inventory (PDI). Schizophrenia Bulletin, 30, 1005–22. PMID 15954204

- Tsuang, M. T., Stone, W. S., & Faraone, S. V. (2000). Toward reformulating the diagnosis of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(7), 1041–1050. PMID 10873908

- Rosenhan, D (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179, 250-8. PMID 4683124Full text as PDF

- McGorry PD, Mihalopoulos C, Henry L, Dakis J, Jackson HJ, Flaum M, Harrigan S, McKenzie D, Kulkarni J, Karoly R. (1995). Spurious precision: procedural validity of diagnostic assessment in psychotic disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 152 (2), 220–3. PMID 7840355

- Read, J. (2004) Does 'schizophrenia' exist? Reliability and validity. In J. Read, L.R. Mosher, R.P. Bentall (eds) Models of Madness: Psychological, Social and Biological Approaches to Schizophrenia. ISBN 1-58391-906-6

- Sato, M. (2004). Renaming schizophrenia: a Japanese perspective. World Psychiatry, 5(1), 53–5. PMID 16757998

- Schizophrenia term use 'invalid'. BBC News Online, (9 October 2006). Retrieved on 2007-05-16.

- Green MF (2001) Schizophrenia Revealed: From Neurons to Social Interactions. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0393703347

- Szasz T (1974) The Myth of Mental Illness: Foundations of a Theory of Personal Conduct. Harper and Row

- Wilkinson G. (1986) Political dissent and "sluggish" schizophrenia in the Soviet Union. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed), 293(6548), 641-2. PMID 3092963

- Lyons, D. (2001). Soviet-style psychiatry is alive and well in the People's Republic. British Journal of Psychiatry, 178, 380-381. PMID 11282823

- Sims, A. (2002) Symptoms in the Mind: An Introduction to Descriptive Psychopathology (3rd edition). Edinburgh: Elsevier Science Ltd. ISBN 0702026271

- Sadock & Sadock, p. 473

- Goldner EM, Hsu L, Waraich P, Somers JM (2002). Prevalence and incidence studies of schizophrenic disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 47(9), 833–43. PMID 12500753

- Ustun TB, Rehm J, Chatterji S, Saxena S, Trotter R, Room R, Bickenbach J, and the WHO/NIH Joint Project CAR Study Group (1999). Multiple-informant ranking of the disabling effects of different health conditions in 14 countries. The Lancet, 354(9173), 111–115. PMID 10408486

- Van Os J. (2004). Does the urban environment cause psychosis? British Journal of Psychiatry, 184 (4), 287–288. PMID 15056569

- Meyer-Lindenberg A, Miletich RS, Kohn PD, et al (2002). Reduced prefrontal activity predicts exaggerated striatal dopaminergic function in schizophrenia. Nature Neuroscience, 5, 267–71. PMID 11865311

- ^ Harrison PJ, Owen MJ. (2003). Genes for schizophrenia? Recent findings and their pathophysiological implications. Lancet, 361(9355), 417–9. PMID 12573388

- Sadock & Sadock. p477

- ^ Sadock & Sadock. p123

- Day R, Nielsen JA, Korten A, Ernberg G, et al (1987). Stressful life events preceding the acute onset of schizophrenia: a cross-national study from the World Health Organization. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 11 (2), 123–205. PMID 3595169

- Harriet L. MacMillan, Jan E. Fleming, David L. Streiner, et al (2001). Childhood Abuse and Lifetime Psychopathology in a Community Sample. American Journal of Psychiatry,158, 1878–83. PMID 11691695

* Schenkel LS, Spaulding WD, Dilillo D, Silverstein SM (2005). Histories of childhood maltreatment in schizophrenia: Relationships with premorbid functioning, symptomatology, and cognitive deficits. Schizophrenia Research Jul 15;76(2–3):273–286. PMID 15949659Full-text available for purchase, Retrieved on 2007-05-16

* Janssen I, Krabbendam L, Bak M, Hanssen M, et al (2004). Childhood abuse as a risk factor for psychotic experiences. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 109, 38–45. PMID 14674957 - ^ Owen MJ, Craddock N, O'Donovan MC. (2005). Schizophrenia: genes at last? Trends in Genetics, 21(9), 518–25. PMID 16009449

- Riley B, Kendler KS (2006). Molecular genetic studies of schizophrenia. Eur J Hum Genet, 14 (6), 669–80. PMID 16721403

- Davies G, Welham J, Chant D, Torrey EF, McGrath J. (2003). A systematic review and meta-analysis of Northern Hemisphere season of birth studies in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 29 (3), 587–93. PMID 14609251

- Brown, A.S. (2006). Prenatal infection as a risk factor for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 32 (2), 200–2. PMID 16469941

- Gregg L, Barrowclough C, Haddock G. (2007) Reasons for increased substance use in psychosis. Clinical Psychology Review, 27 (4), 494-510. PMID 17240501

- Mueser KT, Yarnold PR, Levinson DF, et al (1990). Prevalence of substance abuse in schizophrenia: demographic and clinical correlates. Schizophrenic Bulletin, 16(1), 31–56. PMID 2333480

- Arseneault L, Cannon M, Witton J, Murray RM (2004). Causal association between cannabis and psychosis: examination of the evidence. British Journal of Psychiatry, 184, 110-7. PMID 14754822 Full text available.

- McNeill, Ann (2001). "Smoking and mental health — a review of the literature" (PDF). SmokeFree London Programme. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Meltzer H, Gill B, Petticrew M, Hinds K. (1995). "OPCS Surveys of Psychiatric Morbidity Report 3: Economic Activity and Social Functioning of Adults With Psychiatric Disorders". London, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Available for fee. - Zammit S, Allebeck P, Dalman C, Lundberg I, Hemmingsson T, Lewis G (2003). Investigating the association between cigarette smoking and schizophrenia in a cohort study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160 (12), 2216–21. PMID 14638593

- ^ Compton, Michael T. (2005-11-16). "Cigarette Smoking in Individuals with Schizophrenia". Medscape Psychiatry & Mental Health. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Johnstone EC, Crow TJ, Frith CD, Husband J, Kreel L. (1976). Cerebral ventricular size and cognitive impairment in chronic schizophrenia. Lancet, 30;2 (7992), 924–6. PMID 62160

- Flashman LA, Green MF (2004). Review of cognition and brain structure in schizophrenia: profiles, longitudinal course, and effects of treatment. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 27 (1), 1–18, vii. PMID 15062627

- Green, M.F. (2001) Schizophrenia Revealed: From Neurons to Social Interactions. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-70334-7

- Spencer KM, Nestor PG, Perlmutter R, et al (2004). Neural synchrony indexes disordered perception and cognition in schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101, 17288-93. PMID 15546988 Full text, Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- Konradi C, Heckers S. (2003). Molecular aspects of glutamate dysregulation: implications for schizophrenia and its treatment. Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 97(2), 153–79. PMID 12559388

- Lahti AC, Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, Parwani A, Tamminga CA. (2001). Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology, 25(4), 455–67. PMID 11557159

- Coyle JT, Tsai G, Goff D. (2003). Converging evidence of NMDA receptor hypofunction in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1003, 318–27. PMID 14684455

- Tuominen HJ, Tiihonen J, Wahlbeck K. (2005). Glutamatergic drugs for schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res, 72:225–34. PMID 15560967

- ^ van Os J, Burns T, Cavallaro R, et al (2006). Standardized remission criteria in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 113(2), 91–5. PMID 16423159

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA (1987). The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 13(2), 261–76. PMID 3616518

- The Royal College of Psychiatrists & The British Psychological Society (2003). Schizophrenia. Full national clinical guideline on core interventions in primary and secondary care (PDF). London: Gaskell and the British Psychological Society. Retrieved on 2007-05-17.

- Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Rosenheck RA, Perkins DO, Keefe RS, Davis SM, Davis CE, Lebowitz BD, Severe J, Hsiao JK, Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators. (2005). Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. The New England Journal of Medicine, 353 (12), 1209–23. PMID 16172203

- Leucht S, Wahlbeck K, Hamann J, Kissling W (2003). New generation antipsychotics versus low-potency conventional antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 361(9369), 1581–9. PMID 12747876

- Peet M, Stokes C (2005). Omega-3 fatty acids in the treatment of psychiatric disorders. Drugs, 65(8), 1051–9. PMID 15907142

- Moran, M (2005). Psychosocial Treatment Often Missing From Schizophrenia Regimens. Psychiatr News November 18 2005, Volume 40, Number 22, page 24. Retrieved on 2007-05-17.

- Sadock & Sadock, p. 1148

- McFarlane WR, Dixon L, Lukens E, Lucksted A (2003). Family psychoeducation and schizophrenia: a review of the literature. J Marital Fam Ther. Apr;29(2):223–45. PMID 12728780

- Glynn SM, Cohen AN, Niv N (2007). New challenges in family interventions for schizophrenia. Expert Rev Neurother. Jan;7(1):33–43. PMID 17187495

- Cormac I, Jones C, Campbell C (2002). Cognitive behaviour therapy for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of systematic reviews, (1), CD000524. PMID 11869579

- Zimmermann G, Favrod J, Trieu VH, Pomini V (2005). The effect of cognitive behavioral treatment on the positive symptoms of schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research, 77, 1–9. PMID 16005380

- Kopelowicz A, Liberman RP, Zarate R (2006). Recent advances in social skills training for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2006 Oct;32 Suppl 1:S12–23. PMID 16885207

- Wykes T, Brammer M, Mellers J, et al (2002). Effects on the brain of a psychological treatment: cognitive remediation therapy: functional magnetic resonance imaging in schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry, 181, 144–52. PMID 12151286

- Hogarty GE, Flesher S, Ulrich R, Carter M, et al (2004). Cognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia: effects of a 2-year randomized trial on cognition and behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry. Sep;61(9):866–76.PMID 15351765

- Talwar N, Crawford MJ, Maratos A, Nur U, McDermott O, Procter S (2006). Music therapy for in-patients with schizophrenia: Exploratory randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry. Nov;189:405–9. PMID 17077429 Full text available. "Music therapy may provide a means of improving mental health among people with schizophrenia, but its effects in acute psychoses have not been explored."

- Burton, R. The Anatomy of Melancholy. Project Gutenberg, Retrieved on 2007-05-17. Cf. especially subsection 3, on and after line 3480, "Music a Remedy".

- McGurk, SR, Mueser KT, Feldman K, Wolfe R, Pascaris A (2007). Cognitive training for supported employment: 2–3 year outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. Mar;164(3):437–41. PMID 17329468

- Kulhara P (1994). Outcome of schizophrenia: some transcultural observations with particular reference to developing countries. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 244(5), 227–35. PMID 7893767

- Harding CM, Brooks GW, Ashikaga T, Strauss JS, Breier A (1987). The Vermont longitudinal study of persons with severe mental illness, II: Long-term outcome of subjects who retrospectively met DSM-III criteria for schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144(6), 727–35. PMID 3591992

- Robinson DG, Woerner MG, McMeniman M, Mendelowitz A, Bilder RM (2004). Symptomatic and functional recovery from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 473–479. PMID 14992973

- Hopper K, Wanderling J (2000). Revisiting the developed versus developing country distinction in course and outcome in schizophrenia: results from ISoS, the WHO collaborative followup project. International Study of Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 26 (4), 835–46. PMID 11087016

- Bellack AS (2006). Scientific and Consumer Models of Recovery in Schizophrenia: Concordance, Contrasts, and Implications. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32(3) 432–442. PMID 16461575 Full text available.

- McGuire P (2000). New hope for people with schizophrenia. Monitor on Psychology. 31(2). Retrived on 2007-05-17.

- Sadock & Sadock, p. 485

- Bebbington PE, Kuipers E (1994). The predictive utility of expressed emotion in schizophrenia: an aggregate analysis. Psychological Medicine, 24, 707–718. PMID 7991753

- Hannerz H, Borga P, Borritz M (2001). Life expectancies for individuals with psychiatric diagnoses. Public Health, 115 (5), 328–37. PMID 11593442

- Radomsky ED, Haas GL, Mann JJ, Sweeney JA (1999). Suicidal behavior in patients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(10), 1590–5. PMID 10518171

- Caldwell CB, Gottesman II. (1990). Schizophrenics kill themselves too: a review of risk factors for suicide. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 16(4), 571–89. PMID 2077636

- Pescosolido BA, Monahan J, Link BG, Stueve A, Kikuzawa S (1999). The public's view of the competence, dangerousness, and need for legal coercion of persons with mental health problems. American Journal of Public Health. Sep;89(9):1339–45. PMID 10474550

- ^ Walsh E, Buchanan A, Fahy T (2002). Violence and schizophrenia: examining the evidence. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002 Jun;180:490–5. PMID 12042226

- ^ Stuart, H (2003). Violence and mental illness: an overview. World Psychiatry. June; 2(2): 121–124. PMID 16946914 Full text, Retrieved on 2007-05-17.

- Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al (1998). Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry. May;55(5):393–401. PMID 9596041

- Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Van Dorn RA, Elbogen EB, et al (2006). A national study of violent behavior in persons with schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. May;63(5):490–9. PMID 16651506

- ^ Mullen PE (2006). Schizophrenia and violence: from correlations to preventive strategies. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 12: 239–248. Full text available, Retrieved on 2007-05-17.

- Simpson AI, McKenna B, Moskowitz A, Skipworth J, Barry-Walsh J (2004). Homicide and mental illness in New Zealand, 1970–2000. British Journal of Psychiatry, 185, 394–8. PMID 15516547

- Fazel S, Grann M (2004). Psychiatric morbidity among homicide offenders: a Swedish population study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(11), 2129–31. PMID 15514419

- Brekke JS, Prindle C, Bae SW, Long JD (2001). Risks for individuals with schizophrenia who are living in the community. Psychiatric Services. Oct;52(10):1358–66. PMID 11585953

- Fitzgerald PB, de Castella AR, Filia KM, Filia SL, Benitez J, Kulkarni J (2005). Victimization of patients with schizophrenia and related disorders. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 39(3), 169-74. (1), 187–9. PMID 15701066

- Walsh E, Gilvarry C, Samele C, et al (2004). Predicting violence in schizophrenia: a prospective study. Schizophrenia Research, 67(2–3), 247-52. PMID 14984884

- Solomon PL, Cavanaugh MM, Gelles RJ (2005). Family Violence among Adults with Severe Mental Illness. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, Vol. 6, No. 1, 40–54. PMID 15574672Full text available.

- Chou KR, Lu RB, Chang M (2001). Assaultive behavior by psychiatric in-patients and its related factors. Journal of Nursing Research. Dec;9(5):139–51. PMID 11779087

- Logdberg B, Nilsson LL, Levander MT, Levander S (2004). Schizophrenia, neighbourhood, and crime. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 110(2) Page 92. PMID 15233709 Full text available, Retrieved on 2007-05-16

- Colin, Ross (2004). Schizophrenia: Innovations in Diagnosis and Treatment. Haworth Press. ISBN 0789022699.

- Crow TJ (1997). Schizophrenia as failure of hemispheric dominance for language. Trends in Neurosciences, 20(8), 339–343. PMID 9246721

- Polimeni J, Reiss JP (2002). How shamanism and group selection may reveal the origins of schizophrenia. Medical Hypothesis, 58(3), 244–8. PMID 12018978

- DeMause, Lloyd, "The seven stages of historical personality" in The Emotional Life of Nations (Karnac, 2002). Available at primal-page.com, Retrieved on 2007-05-17.

- Kurtz, Paul (1986). The Transcendental Temptation: A Critique of Religion and the Paranormal (Prometheus Books) ISBN 0-87975-645-4

- Dohan FC (1970). Coeliac disease and schizophrenia. Lancet, 1970 April 25;1(7652):897-8. PMID 4191543

- Dohan FC (1973). Coeliac disease and schizophrenia. British Medical Journal, 3(5870): 51–52. PMID 4740433

- Dohan FC (1979). Celiac-type diets in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry, 1979 May;136(5):732-3. PMID 434265

- Kalaydjian AE, Eaton W, Cascella N, Fasano A (2006). The gluten connection: the association between schizophrenia and celiac disease. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006 Feb;113(2):82–90. PMID 16423158

References

- Sadock BJ, Sadock VA (2003). Kaplan & Sadock's Synopsis of Psychiatry, Ninth Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-3183-6.

Further reading

- Bentall, R. (2003) Madness explained: Psychosis and Human Nature. London: Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 0-7139-9249-2

- Boyle, Mary, (1993), Schizophrenia: A Scientific Delusion, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-09700-2

- Deveson, Anne (1991), Tell Me I'm Here. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-027257-7

- Fallon, James H. et al. (2003) The Neuroanatomy of Schizophrenia: Circuitry and Neurotransmitter Systems. Clinical Neuroscience Research 3:77–107. Available at Elsevier article locater.

- Green, M.F. (2001) Schizophrenia Revealed: From Neurons to Social Interactions. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-70334-7

- Jones, S. and Hayward, P. (2004) Coping with Schizophrenia: A Guide for Patients, Families and Caregivers. ISBN 1-85168-344-5

- Keen, T. M. (1999) Schizophrenia: orthodoxy and heresies. A review of alternative possibilities. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 1999, 6, 415–424. PMID 10818864Full-text (PDF), Retrieved on 2007-05-17.

- Noll, Richard (2007) The Encyclopedia of Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders, Third Edition ISBN 0-8160-6405-9

- Read, J., Mosher, L.R., Bentall, R. (2004) Models of Madness: Psychological, Social and Biological Approaches to Schizophrenia. ISBN 1-58391-906-6. A critical approach to biological and genetic theories, and a review of social influences on schizophrenia.

- Shaner, A., Miller, G. F., & Mintz, J. (2004). Schizophrenia as one extreme of a sexually selected fitness indicator. Schizophrenia Research, 70(1), 101–109. PMID 15246469Full text (PDF), Retrieved on 2007-05-17.

- Szasz, T. (1976) Schizophrenia: The Sacred Symbol of Psychiatry. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-07222-4

- Tausk, V. : "Sexuality, War, and Schizophrenia: Collected Psychoanalytic Papers", Publisher: Transaction Publishers 1991, ISBN 0-88738-365-3 (On the Origin of the 'Influencing Machine' in Schizophrenia.)

- Torrey, E.F., M.D. (2006) Surviving Schizophrenia: A Manual for Families, Consumers, and Providers (5th Edition). Quill (HarperCollins Publishers) ISBN 0-06-084259-8

- Wiencke, Markus (2006) Schizophrenie als Ergebnis von Wechselwirkungen: Georg Simmels Individualitätskonzept in der Klinischen Psychologie. In David Kim (ed.), Georg Simmel in Translation: Interdisciplinary Border-Crossings in Culture and Modernity (pp. 123–155). Cambridge Scholars Press, Cambridge, ISBN 1-84718-060-5

External links

- Template:Dmoz

- Template:Dmoz — Support Groups

- Template:Dmoz — Articles and research

- News, information and further description

- DSM V scholarly debates on schizophrenia

- NPR: the sight and sounds of schizophrenia

- National Mental Health Association fact sheet on schizophrenia

- Understanding Schizophrenia - A factsheet from the mental health charity Mind

- World Health Organisation data on schizophrenia from 'The World Health Report 2001. Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope'

- National Institute of Mental Health (USA) Schizophrenia information

- The current World Health Organisation definition of Schizophrenia

- Schizophrenia in history

- Symptoms in Schizophrenia Film made in 1940 showing some of the symptoms of Schizophrenia.

- Open The Doors - information on global programme to fight stigma and discrimination because of Schizophrenia. The World Psychiatric Association (WPA)

- Scientific American Magazine (January 2004 Issue) Decoding Schizophrenia

- Symptoms, causes and treatment of schizophrenia

- Critical approaches to schizophrenia

- Bola, John R., Ph.D.; & Mosher, Loren R., M.D. (2003). Treatment of Acute Psychosis Without Neuroleptics: Two-Year Outcomes From the Soteria Project. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, (191: 219–229). Available as PDF.

- Leo, Jonathan Ph.D., & Jay Joseph, Psy. D. Schizophrenia: Medical students are taught it's all in the genes, but are they hearing the whole story?

- Mosher, Loren M.D. (Chief of the Center for Studies of Schizophrenia at the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health 1969–1980) Still Crazy After All These Years

| Mental disorders (Classification) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

Categories: