| Revision as of 20:42, 24 June 2007 editRjwilmsi (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers931,877 editsm fix my earlier edit, add language tags← Previous edit | Revision as of 15:27, 30 July 2007 edit undoVolkovBot (talk | contribs)447,718 editsm robot Adding: tg:Эдмон АбуNext edit → | ||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

Revision as of 15:27, 30 July 2007

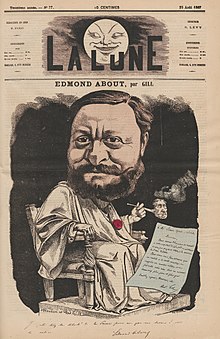

Edmond François Valentin About (February 14, 1828 – January 16, 1885), was a French novelist, publicist and journalist.

He was born at Dieuze, in the Moselle département in the Lorraine region of France. In 1848 he entered the École Normale, taking second place in the annual competition for admission in which Hippolyte Taine came first. Among his college contemporaries, besides Taine, were Francisque Sarcey, Challemel-Lacour and the ill-starred Prevost-Paradol. Of them all, About was considered the most highly vitalized, exuberant, brilliant and "undisciplined". At the end of his college career he joined the French school in Athens, but himself claimed that it had never been his intention to follow the professorial career for which the École Normale was a preparation, and in 1853 he returned to France and devoted himself to literature and journalism.

He was perhaps the most entertaining anti-clerical writer of his period. His tales have the qualities of the best writing of the 18th century century, enhanced by the modern interest of his own century. Le roi des montagnes (The King of the Mountains) is the best-known of his novels. In 1854 About was working as a poor archaeologist at the French School at Athens, where he noticed there was a curious understanding between the brigands and the police of modern Greece. Brigandage was becoming a safe and almost a respectable Greek industry. "Why not make it quite respectable and regular?" said About. "Why does not some brigand chief, with a good connection, convert his business into a properly registered joint-stock company?" So he produced, in 1856, one of the most delightful of satirical novels, Le roi des montagnes.

His book on Greece, La Grèce contemporaine (1855), which did not spare Greek susceptibilities, was an immediate success. In Tolla (1855) About was charged with drawing too freely on an earlier Italian novel, Vittoria Savelli (1841). This aroused prejudice against him, and he was the object of numerous attacks, to which he was ready to respond. The Lettres d'un bon jeune homme, written to the Figaro under the signature of "Valentin de Quevilly", provoked more animosities. During the next few years, with indefatigable energy, and generally with full public recognition, he wrote novels, stories, a play (which failed), a book-pamphlet on the Roman question, many pamphlets on other subjects of the day, newspaper articles innumerable, some art criticisms, rejoinders to the attacks of his enemies, and popular manuals of political economy, L'A B C du travailleur (1868), Le progrès (1864).

About's attitude towards the empire was friendly but critical. He greeted the liberal ministry of Émile Ollivier at the beginning of 1870 with delight, and welcomed the Franco-German War. But as a result of the war he lost the loved home near Saverne in Alsace, which he had purchased in 1858 out of the fruits of his earlier literary successes. With the fall of the empire he became a republican, and, an inveterate anti-clerical, he threw himself into the battle against the conservative reaction which made way during the first years of the republic. From 1872 onwards for some five or six years his paper, the XIX Siècle, of which he was the heart and soul, became a power in the land. But the republicans never quite forgave the tardiness of his conversion, and no place rewarded his later zeal. On January 23 1884 he was elected a member of the Académie française, but died before taking his seat. His journalism — of which specimens in his earlier and later manners will be found in the two series of Lettres d'un bon jeune homme à sa cousine Madeleine (1861 and 1863), and the posthumous collection, Le dix-neuvieme siècle (1892) — was of its nature ephemeral. So were the pamphlets, great and small. His political economy was that of an orthodox popularizer, and in no sense epoch-making. His dramas are negligible. His more serious novels, Madelon (1863), L'Infâme (1867), the three that form the trilogy of the Vieille Roche (1866), and Le roman d'un brave homme (1880) — a kind of counterblast to the view of the French workman presented in Zola's Assommoir — contain striking and amusing scenes, no doubt, but scenes which are often suggestive of the stage, while description, dissertation, explanation too frequently take the place of life. His best work after all is to be found in the books that are almost wholly farcical, Le nez d'un notaire (1862); Le roi des montagnes (1856); L'homme à l'oreille cassée (1862); Trente et quarante (1858); Le cas de M. Guérin (1862). Here his most genuine wit, his sprightliness, his vivacity, the fancy that was in him, have free play. "You will never be more than a little Voltaire," said one of his masters when he was a lad at school. It was a true prophecy.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)- Benjamin Willis Wells, A Century of French Fiction, s. v., About

External links

| Preceded byJules Sandeau | Seat 11 Académie française 1884–1885 |

Succeeded byLéon Say |