| Revision as of 20:02, 4 April 2008 view sourceRicky81682 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users161,010 edits rm redirect and I think "of PA in Pennsylvania" is just odd← Previous edit | Revision as of 01:15, 5 April 2008 view source Fiching (talk | contribs)1 edit →EducationNext edit → | ||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

| ==Education== | ==Education== | ||

| Marshall graduated from ] in Pennsylvania in 1930. Afterward, Marshall wanted to apply to his hometown law school, the ], but the dean told him that he would not be accepted due to the school's ] policy. Later, as a civil rights litigator, he successfully sued the school for this policy in the case of '']''. Instead, Marshall sought admission and was accepted at ]. He was influenced by its new dean, ], who instilled in his students the desire to apply the tenets of the Constitution to all Americans. Marshall was a member of ], the first intercollegiate Black ] ], established by ] students in 1906. | Marshall graduated from ] in Pennsylvania in 1930. Afterward, Marshall wanted to apply to his hometown law school, the ], but the dean told him that he would not be accepted due to the school's ] policy. Later, as a civil rights litigator, he successfully sued the school for this policy in the case of '']''. Instead, Marshall sought admission and was accepted at ]. He was influenced by its new dean, ], who instilled in his students the desire to apply the tenets of the Constitution to all Americans. Marshall was a member of ], the first intercollegiate Black ] ], established by ] students in 1906. | ||

| Born July 2, 1908 in Baltimore, Maryland, he graduated from Lincoln University in Oxford, Pennsylvania. | |||

| He served as counsel and chief counsel for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and argued the groundbreaking case of Brown vs. Board of Education before the United States Supreme Court which effectively made segregration of the races in public schools illegal. | |||

| In 1967, President Lyndon Johnson appointed him to the Supreme Court, replacing the retiring Justice Tom Clark of Texas. He was the first black to serve on the Court and was, in most reports, an almost larger-than-life figure there. | |||

| He stepped down from the Court in July 1991 due to failing health and died of heart failure on January 24, 1993 at Bethesda Naval Medical Center in Maryland. | |||

| He was buried in Section 5 of Arlington National Cemetery, near the graves of fellow Justices, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., William O. Douglas, William J. Brennan and Potter Stewart. | |||

| -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | |||

| January 25, 1993 | |||

| OBITUARY | |||

| Thurgood Marshall, Civil Rights Hero, Dies at 84 | |||

| Thurgood Marshall, pillar of the civil rights revolution, architect of the legal strategy that ended the era of official segregation and the first black Justice of the Supreme Court, died today. A major figure in American public life for a half-century, he was 84 years old. | |||

| Toni House, the Court's spokeswoman, said Justice Marshall died of heart failure at Bethesda Naval Medical Center in Maryland at 2 P.M. | |||

| Justice Marshall, who retired from the High Court in 1991, had been scheduled to administer the oath of office to Vice President Al Gore on Wednesday, but his failing health prevented him from doing so. | |||

| Thurgood Marshall was a figure of history well before he began his 24-year service on the Supreme Court on Oct. 2, 1967. | |||

| During more than 20 years as director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, he was the principal architect of the strategy of using the courts to provide what the political system would not: a definition of equality that assured black Americans the full rights of citizenship. | |||

| Landmark Triumph in 1954 | |||

| His greatest legal victory came in 1954 with the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which declared an end to the "separate but equal" system of racial segregation then in effect in the public schools of 21states. | |||

| Despite the years of turmoil that followed the unanimous decision, the Court left no doubt that it was bringing an end to the era of official segregation in all public institutions. Many questions lingered after so monumental a transformation, and the Court continued to confront issues involving the legacy of segregation even after Justice Marshall retired. | |||

| As a civil rights lawyer, Mr. Marshall devised the legal strategy and headed the team that brought the school desegregation issue before the Court. An experienced Supreme Court advocate by that time, he argued the case himself in the straightforward, plain-spoken manner that was the hallmark of his courtroom style. Asked by Justice Felix Frankfurter during the argument what he meant by "equal," Mr. Marshall replied, "Equal means getting the same thing, at the same time, and in the same place." | |||

| He won many other important civil rights cases, including a challenge to the whites-only primary elections in Texas. This device was commonly used by white Southern politicians to disenfranchise blacks. | |||

| He also won a major Supreme Court case in which the Court declared that restrictive covenants that barred blacks from buying or renting homes could not be enforced in state courts. | |||

| 'Heroic Imagination' In a Ruthless World | |||

| Mr. Marshall, who was born and reared in Baltimore, was excluded from the all-white law school at the University of Maryland. Later he brought successful lawsuits that integrated not only that school but also several other state university systems. He received his legal education at the law school of Howard University in Washington, D.C., the nation's pre-eminent black university, where he graduated first in his class in 1933 and made the personal and intellectual connections that shaped his future career. | |||

| Years later, the University of Maryland named its law library for him, and the City of Baltimore honored him by placing a bronze likeness, more than eight feet tall, outside the Federal courthouse. | |||

| "To do what he did required a heroic imagination," Paul Gewirtz, one of Justice Marshall's former law clerks, wrote in a tribute published after the Justice retired from the Court. | |||

| The article by Mr. Gewirtz, the Potter Stewart Professor of Constitutional Law at Yale Law School, continued: "He grew up in a ruthlessly discriminatory world -- a world in which segregation of the races was pervasive and taken for granted, where lynching was common, where the black man's inherent inferiority was proclaimed widely and wantonly. Thurgood Marshall had the capacity to imagine a radically different world, the imaginative capacity to believe that such a world was possible, the strength to sustain that image in the mind's eye and the heart's longing, and the courage and ability to make that imagined world real." | |||

| Yet Justice Marshall was not satisfied with what he had achieved, believing that the Constitution's promise of equality remained unfulfilled and that his work was therefore unfinished. | |||

| A Voice of Anger And Disappointment | |||

| For much of his Supreme Court career, as the Court's majority increasingly drew back from affirmative action and other remedies for discrimination that he believed were still necessary to combat the nation's legacy of racism, Justice Marshall used dissenting opinions to express his disappointment and anger. | |||

| In 1978, for example, in the Bakke case, in which the Court found it unconstitutional for a state-run medical school to reserve 16 of 100 places in the entering class for black and other minority students, Justice Marshall filed | |||

| a separate 16-page opinion tracing the black experience in America. | |||

| "In light of the sorry history of discrimination and its devastating impact on the lives of Negroes," he wrote, "bringing the Negro into the mainstream of American life should be a state interest of the highest order. To fail to do so is to insure that America will forever remain a divided society." | |||

| He dissented in City of Richmond v. Croson, a 1989 ruling in which the Court declared unconstitutional a municipal ordinance setting aside 30 percent of public contracting dollars for companies owned by blacks or members of other minorities. The Court majority called the program a form of state-sponsored racism that was no less offensive to the Constitution than a policy officially favoring whites. | |||

| In his dissenting opinion, Justice Marshall said that in reaching that conclusion "a majority of this Court signals that it regards racial discrimination as largely a phenomenon of the past, and that government bodies need no longer preoccupy themselves with rectifying racial injustice." | |||

| He added: "I, however, do not believe this nation is anywhere close to eradicating racial discrimination or its vestiges. In constitutionalizing its wishful thinking, the majority today does a grave disservice not only to those victims of past and present racial discrimination in this nation whom government has sought to assist, but also to this Court's long tradition of approaching issues of race with the utmost sensitivity." | |||

| ==Law career== | ==Law career== | ||

Revision as of 01:15, 5 April 2008

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Thurgood Marshall" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (May 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

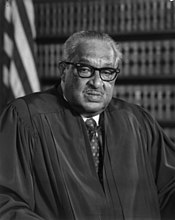

| Thurgood Marshall | |

|---|---|

Thurgood Marshall Thurgood Marshall | |

| Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court | |

| In office June 13 1967 – June 28 1991 | |

| Nominated by | Lyndon B. Johnson |

| Preceded by | Tom C. Clark |

| Succeeded by | Clarence Thomas |

Thurgood Marshall (July 2, 1908 – January 24, 1993) was an American jurist and the first African American to serve on the Supreme Court of the United States. Prior to becoming a judge, he was a lawyer who was best remembered for his high success rate in arguing before the Supreme Court and for the victory in Brown v. Board of Education.

Marshall was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on July 2, 1908. His original name was Thoroughgood but he shortened it to Thurgood in second grade. His father, William Marshall, instilled in him an appreciation for the Constitution of the United States and the rule of law. Additionally, as a child, he was punished for his school misbehavior by being forced to read the Constitution, which he later said piqued his interest in the document. Marshall was a descendant of slaves.

Marshall was married twice; to Vivian "Buster" Burey from 1929 until her death in February 1955 and to Cecilia Suyat from December 1955 until his own death in 1993. He had two sons from his second marriage; Thurgood Marshall, Jr., who is a former top aide to President Bill Clinton, and John W. Marshall, who is a former United States Marshals Service Director and since 2002 has served as Virginia Secretary of Public Safety under Governors Mark Warner and Tim Kaine.

Education

Marshall graduated from Lincoln University in Pennsylvania in 1930. Afterward, Marshall wanted to apply to his hometown law school, the University of Maryland School of Law, but the dean told him that he would not be accepted due to the school's segregation policy. Later, as a civil rights litigator, he successfully sued the school for this policy in the case of Murray v. Pearson. Instead, Marshall sought admission and was accepted at Howard University. He was influenced by its new dean, Charles Hamilton Houston, who instilled in his students the desire to apply the tenets of the Constitution to all Americans. Marshall was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha, the first intercollegiate Black Greek-letter fraternity, established by African American students in 1906.

Born July 2, 1908 in Baltimore, Maryland, he graduated from Lincoln University in Oxford, Pennsylvania.

He served as counsel and chief counsel for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and argued the groundbreaking case of Brown vs. Board of Education before the United States Supreme Court which effectively made segregration of the races in public schools illegal.

In 1967, President Lyndon Johnson appointed him to the Supreme Court, replacing the retiring Justice Tom Clark of Texas. He was the first black to serve on the Court and was, in most reports, an almost larger-than-life figure there.

He stepped down from the Court in July 1991 due to failing health and died of heart failure on January 24, 1993 at Bethesda Naval Medical Center in Maryland.

He was buried in Section 5 of Arlington National Cemetery, near the graves of fellow Justices, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., William O. Douglas, William J. Brennan and Potter Stewart.

January 25, 1993 OBITUARY Thurgood Marshall, Civil Rights Hero, Dies at 84 Thurgood Marshall, pillar of the civil rights revolution, architect of the legal strategy that ended the era of official segregation and the first black Justice of the Supreme Court, died today. A major figure in American public life for a half-century, he was 84 years old.

Toni House, the Court's spokeswoman, said Justice Marshall died of heart failure at Bethesda Naval Medical Center in Maryland at 2 P.M.

Justice Marshall, who retired from the High Court in 1991, had been scheduled to administer the oath of office to Vice President Al Gore on Wednesday, but his failing health prevented him from doing so.

Thurgood Marshall was a figure of history well before he began his 24-year service on the Supreme Court on Oct. 2, 1967.

During more than 20 years as director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, he was the principal architect of the strategy of using the courts to provide what the political system would not: a definition of equality that assured black Americans the full rights of citizenship.

Landmark Triumph in 1954

His greatest legal victory came in 1954 with the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which declared an end to the "separate but equal" system of racial segregation then in effect in the public schools of 21states.

Despite the years of turmoil that followed the unanimous decision, the Court left no doubt that it was bringing an end to the era of official segregation in all public institutions. Many questions lingered after so monumental a transformation, and the Court continued to confront issues involving the legacy of segregation even after Justice Marshall retired.

As a civil rights lawyer, Mr. Marshall devised the legal strategy and headed the team that brought the school desegregation issue before the Court. An experienced Supreme Court advocate by that time, he argued the case himself in the straightforward, plain-spoken manner that was the hallmark of his courtroom style. Asked by Justice Felix Frankfurter during the argument what he meant by "equal," Mr. Marshall replied, "Equal means getting the same thing, at the same time, and in the same place."

He won many other important civil rights cases, including a challenge to the whites-only primary elections in Texas. This device was commonly used by white Southern politicians to disenfranchise blacks.

He also won a major Supreme Court case in which the Court declared that restrictive covenants that barred blacks from buying or renting homes could not be enforced in state courts.

'Heroic Imagination' In a Ruthless World

Mr. Marshall, who was born and reared in Baltimore, was excluded from the all-white law school at the University of Maryland. Later he brought successful lawsuits that integrated not only that school but also several other state university systems. He received his legal education at the law school of Howard University in Washington, D.C., the nation's pre-eminent black university, where he graduated first in his class in 1933 and made the personal and intellectual connections that shaped his future career.

Years later, the University of Maryland named its law library for him, and the City of Baltimore honored him by placing a bronze likeness, more than eight feet tall, outside the Federal courthouse.

"To do what he did required a heroic imagination," Paul Gewirtz, one of Justice Marshall's former law clerks, wrote in a tribute published after the Justice retired from the Court.

The article by Mr. Gewirtz, the Potter Stewart Professor of Constitutional Law at Yale Law School, continued: "He grew up in a ruthlessly discriminatory world -- a world in which segregation of the races was pervasive and taken for granted, where lynching was common, where the black man's inherent inferiority was proclaimed widely and wantonly. Thurgood Marshall had the capacity to imagine a radically different world, the imaginative capacity to believe that such a world was possible, the strength to sustain that image in the mind's eye and the heart's longing, and the courage and ability to make that imagined world real."

Yet Justice Marshall was not satisfied with what he had achieved, believing that the Constitution's promise of equality remained unfulfilled and that his work was therefore unfinished.

A Voice of Anger And Disappointment

For much of his Supreme Court career, as the Court's majority increasingly drew back from affirmative action and other remedies for discrimination that he believed were still necessary to combat the nation's legacy of racism, Justice Marshall used dissenting opinions to express his disappointment and anger.

In 1978, for example, in the Bakke case, in which the Court found it unconstitutional for a state-run medical school to reserve 16 of 100 places in the entering class for black and other minority students, Justice Marshall filed a separate 16-page opinion tracing the black experience in America.

"In light of the sorry history of discrimination and its devastating impact on the lives of Negroes," he wrote, "bringing the Negro into the mainstream of American life should be a state interest of the highest order. To fail to do so is to insure that America will forever remain a divided society."

He dissented in City of Richmond v. Croson, a 1989 ruling in which the Court declared unconstitutional a municipal ordinance setting aside 30 percent of public contracting dollars for companies owned by blacks or members of other minorities. The Court majority called the program a form of state-sponsored racism that was no less offensive to the Constitution than a policy officially favoring whites.

In his dissenting opinion, Justice Marshall said that in reaching that conclusion "a majority of this Court signals that it regards racial discrimination as largely a phenomenon of the past, and that government bodies need no longer preoccupy themselves with rectifying racial injustice."

He added: "I, however, do not believe this nation is anywhere close to eradicating racial discrimination or its vestiges. In constitutionalizing its wishful thinking, the majority today does a grave disservice not only to those victims of past and present racial discrimination in this nation whom government has sought to assist, but also to this Court's long tradition of approaching issues of race with the utmost sensitivity."

Law career

Main article: Murray v. PearsonMarshall received his law degree from Howard in 1933, and set up a private practice in Baltimore. The following year, he began working with the Baltimore NAACP. He won his first major civil rights case, Murray v. Pearson, 169 Md. 478 (1936). This involved the first attempt to chip away at Plessy v. Ferguson, a plan created by his co-counsel on the case Charles Hamilton Houston. Marshall represented Donald Gaines Murray, a black Amherst College graduate with excellent credentials who had been denied admission to the University of Maryland Law School because of its separate but equal policies. This policy required black students to accept one of three options, attend: Morgan College, the Princess Anne Academy, or out-of-state black institutions. In 1935, Thurgood Marshall argued the case for Murray, showing that neither of the in-state institutions offered a law school and that such schools were entirely unequal to the University of Maryland. Marshall and Houston expected to lose and intended to appeal to the federal courts. However, the Maryland Court of Appeals ruled against the state of Maryland and its Attorney General, who represented the University of Maryland, stating "Compliance with the Constitution cannot be deferred at the will of the state. Whatever system is adopted for legal education now must furnish equality of treatment now". While it was a moral victory, the ruling had no real authority outside the state of Maryland.

Chief Counsel for the NAACP

Marshall won his very first U.S. Supreme Court case, Chambers v. Florida, 309 U.S. 227 (1940). At the age of 32, that same year, he was appointed Chief Counsel for the NAACP. He argued many other cases before the Supreme Court, most of them successfully, including Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944); Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948); Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950); and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637 (1950). His most famous case as a lawyer was Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), the case in which the Supreme Court ruled that "separate but equal" public education was unconstitutional because it could never be truly equal. In total, Marshall won 29 out of the 32 cases he argued before the Supreme Court.

During the 1950s, Thurgood Marshall developed a friendly relationship with J. Edgar Hoover, the director the Federal Bureau of Investigation. In 1956, for example, he privately praised Hoover's campaign to discredit T.R.M. Howard, a maverick civil rights leader from Mississippi. During a national speaking tour, Howard had criticized the FBI's failure to seriously investigate cases such as the 1955 murders of George W. Lee and Emmett Till. Ironically, two years earlier Howard had arranged for Marshall to deliver a well-received speech at a rally of his Regional Council of Negro Leadership in Mound Bayou, Mississippi only days before the Brown decision.

President John F. Kennedy appointed Marshall to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in 1961. A group of Democratic Party Senators led by Mississippi's James Eastland held up his confirmation, so he served for the first several months under a recess appointment. Marshall remained on that court until 1965, when President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed him Solicitor General.

U.S. Supreme Court

On June 13, 1967, President Johnson appointed Marshall to the Supreme Court following the retirement of Justice Tom C. Clark, saying that this was "the right thing to do, the right time to do it, the right man and the right place." He was the 96th person to hold the position, and the first African-American. President Johnson confidently predicted to one biographer, Doris Kearns Goodwin, that a lot of black baby boys would be named "Thurgood" in honor of this choice (in fact, Kearns's research of birth records in New York and Boston indicates that Johnson's prophecy did not come true).

Marshall served on the Court for the next twenty-four years, compiling a liberal record that included strong support for Constitutional protection of individual rights, especially the rights of criminal suspects against the government. His most frequent ally on the Court (indeed, the pair rarely voted at odds) was Justice William Brennan, who consistently joined him in supporting abortion rights and opposing the death penalty. Brennan and Marshall concluded in Furman v. Georgia that the death penalty was, in all circumstances, unconstitutional, and never accepted the legitimacy of Gregg v. Georgia, which ruled four years later that the death penalty was constitutional in some circumstances. Thereafter, Brennan or Marshall dissented from every denial of certiorari in a capital case and from every decision upholding a sentence of death.

Although he is best remembered for his jurisprudence in the fields of civil rights and criminal procedure, Marshall made significant contributions to other areas of the law as well. In Teamsters v. Terry he held that the Seventh Amendment entitled the plaintiff to a jury trial in a suit against a labor union for breach of duty of fair representation. In TSC Industries, Inc. v. Northway, Inc. he articulated a formulation for the standard of materiality in United States securities law that is still applied and used today. In Cottage Savings Association v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, he weighed in on the income tax consequences of the Savings and Loan crisis, permitting a savings and loan association to deduct a loss from an exchange of mortgage participation interests.

Among his many law clerks were Chief Judge Douglas Ginsburg of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, well-known law professors Cass Sunstein, Eben Moglen, Susan Low Bloch, and Mark Tushnet, Dean Richard Revesz of New York University School of Law, and Dean Elena Kagan of Harvard Law School.

Death

Marshall died of heart failure at the age of 84. He died at the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, at 2:58 p.m. on January 24, 1993. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. He was survived by his second wife and their two sons. Marshall left all of his personal papers and notes to the Library of Congress. The Librarian of Congress opened Marshall's papers for immediate use by scholars, journalists and the public, insisting that this was Marshall's intent. The Marshall family and several of his close associates disputed this claim. There are numerous memorials to Justice Marshall. One is near the Maryland State House. The primary office building for the federal court system, located on Capitol Hill in Washington D.C., is named in honor of Justice Marshall and also contains a statue of him in the atrium. The major airport serving Baltimore and the Maryland suburbs of Washington, DC, was renamed the Baltimore-Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport on October 1, 2005.

Timeline of Marshall's life

1930 - Thurgood graduates with honors from Lincoln University, PA (cum laude).

1934 - Thurgood receives law degree from Howard University (magna cum laude); begins private practice in Baltimore, Maryland.

1934 - Begins to work for Baltimore branch of NAACP.

1935 - Worked with Charles Houston, wins first major civil rights case, Murray v. Pearson.

1936 - Becomes assistant special counsel for NAACP in New York.

1940 - Wins Chambers v. Florida, the first of twenty-nine Supreme Court victories.

1943 - Won case for integration of schools in Hillburn, New York.

1944 - Successfully argues Smith v. Allwright, overthrowing the South's "white primary".

1946 -Thurgood Marshall received a medal from the NAACP.

1948 - Wins Shelley v. Kraemer, in which Supreme Court strikes down legality of racially restrictive covenants.

1950 - Wins Supreme Court victories in two graduate-school integration cases, Sweatt v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents.

1951 - Visits South Korea and Japan to investigate charges of racism in U.S. armed forces. He reported that the general practice was one of "rigid segregation."

1954 - Wins Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, landmark case that demolishes legal basis for segregation in America.

1956 - Wins Browder v. Gayle, ending the practice of segregation on buses and ending the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

1961 - Defends civil rights demonstrators, winning Supreme Court victory in Garner v. Louisiana; nominated to Second Circuit Court of Appeals by President J.F. Kennedy.

1961 - Appointed circuit judge, makes 112 rulings, none of them reversed on certiorari by Supreme Court (1961-1965).

1965 - Appointed United States Solicitor General by President Lyndon B. Johnson; wins 14 of the 19 cases he argues for the government (1965-1967).

1967 - Becomes first African American elevated to U.S. Supreme Court (1967-1991).

1991 - Retires from the Supreme Court.

1992 - Receives the Liberty Medal recognizing Marshall's long history of protecting individual rights under the Constitution.

1993 - Dies at age 84 in Bethesda, Maryland, near Washington, D.C.

For more, see Bradley C. S. Watson, "The Jurisprudence of William Joseph Brennan, Jr., and Thurgood Marshall" in History of American Political Thought.

References

- Juan Williams, Thurgood Marshall: American Revolutionary (1998 book). Promotional site for book

- David T. Beito and Linda Royster Beito, T.R.M. Howard: Pragmatism over Strict Integrationist Ideology in the Mississippi Delta, 1942-1954 in Glenn Feldman, ed., Before Brown: Civil Rights and White Backlash in the Modern South (2004 book), 68-95.

Notes

- Schools and race | Still separate after all these years | Economist.com

- American Public Radio: Cissy Marshall

- According to the Social Security Administration Popular baby name database, Thurgood has never been in the top 1000 of male baby names.

- Lewis, Neil A. (May 26, 1993). "Chief Justice Assails Library On Release of Marshall Papers". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded byNew seat | Judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit 1962-1965 |

Succeeded byWilfred Feinberg |

| Preceded byArchibald Cox | Solicitor General 1965–1967 |

Succeeded byErwin N. Griswold |

| Preceded byTom C. Clark | Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States October 2, 1967 – October 1, 1991 |

Succeeded byClarence Thomas |

Template:Start U.S. Supreme Court composition Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1967-1969 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition CJ Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1969 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1970-1971 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1972-1975 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1975-1981 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1981-1986 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition CJ Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1986-1987 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1988-1990 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1990-1991 Template:End U.S. Supreme Court composition

Categories:- United States Supreme Court justices

- Solicitors General of the United States

- Judges of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

- National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

- African American politicians

- African Americans' rights activists

- Maryland lawyers

- Howard University alumni

- Lincoln University (Pennsylvania) alumni

- American Episcopalians

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- People from Baltimore, Maryland

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- 1908 births

- 1993 deaths