| Revision as of 12:03, 11 April 2008 view sourceGrandmaster (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers25,517 editsmNo edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 02:21, 12 April 2008 view source Iberieli (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users2,219 edits azeri name, albania was not armenian kingdomNext edit → | ||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

| :''This region should not be confused with modern-day ]'' in south-eastern ]. | :''This region should not be confused with modern-day ]'' in south-eastern ]. | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| '''Caucasian Albania''', also known as '''Aghvank''' (in {{lang-hy|Աղվանք}})<ref name="Minorsky">V. Minorsky. ''Caucasica IV.'' Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 15, No. 3. (1953), p. 504</ref><ref name="Olson" />, '''Ardhan''' (in ]), '''Arran''' (in ])<ref name="Bosworth"></ref>, '''Al-Ran''' (in ])<ref name="Minorsky" /><ref name="Bosworth" />, and '''Albanoi''' (in ])<ref name="Olson">]. An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. ISBN 0313274975</ref> was an ancient kingdom that existed on the territory of present-day ] and southern ]. The name "Albania" is ], and denotes "mountainous land";<ref name="Olson"/> the contemporaneous native name for the country is unknown.<ref name="Hewsen">Robert H. Hewsen. "Ethno-History and the Armenian Influence upon the Caucasian Albanians," in: Samuelian, Thomas J. (Hg.), ''Classical Armenian Culture. Influences and Creativity'', Chicago: 1982, 27-40.</ref> | '''Caucasian Albania''', also known as '''Aghvank''' (in {{lang-az|Qafqaz Albaniyası}}), (in {{lang-hy|Աղվանք}})<ref name="Minorsky">V. Minorsky. ''Caucasica IV.'' Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 15, No. 3. (1953), p. 504</ref><ref name="Olson" />, '''Ardhan''' (in ]), '''Arran''' (in ])<ref name="Bosworth"></ref>, '''Al-Ran''' (in ])<ref name="Minorsky" /><ref name="Bosworth" />, and '''Albanoi''' (in ])<ref name="Olson">]. An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. ISBN 0313274975</ref> was an ancient kingdom that existed on the territory of present-day ] and southern ]. The name "Albania" is ], and denotes "mountainous land";<ref name="Olson"/> the contemporaneous native name for the country is unknown.<ref name="Hewsen">Robert H. Hewsen. "Ethno-History and the Armenian Influence upon the Caucasian Albanians," in: Samuelian, Thomas J. (Hg.), ''Classical Armenian Culture. Influences and Creativity'', Chicago: 1982, 27-40.</ref> | ||

| == Ancient population of Caucasian Albania== | == Ancient population of Caucasian Albania== | ||

Revision as of 02:21, 12 April 2008

Caucasian Albania, also known as Aghvank (in Template:Lang-az), (in Template:Lang-hy), Ardhan (in Parthian), Arran (in Persian), Al-Ran (in Arabic), and Albanoi (in Greek) was an ancient kingdom that existed on the territory of present-day Republic of Azerbaijan and southern Dagestan. The name "Albania" is Latin, and denotes "mountainous land"; the contemporaneous native name for the country is unknown.

Ancient population of Caucasian Albania

Caucasian Albanians were one of the Ibero-Caucasian peoples, the ancient and indigenous population of modern southern Dagestan and Azerbaijan. Ancient chronicles provide the names of some tribes that populated Caucasian Albania, including the regions of Artsakh and Utik. These were Utians, Mycians, Caspians, Gargarians, Sakasenians, Gelians, Sodians, Lupenians, Balasanians, Parsians and Parrasians. According to Robert H. Hewsen, these tribes were "certainly not of Armenian origin", and "although certain Iranian peoples must have settled here during the long period of Persian and Median rule, most of the natives were not even Indo-Europeans". Strabo wrote of the Caucasian Albanians in the first century BC:

At the present time, indeed, one king rules all the tribes, but formerly the several tribes were ruled separately by kings of their own according to their several languages. They have twenty-six languages, because they have no easy means of intercourse with one another

The Mannaeans maintained one of the earliest states recorded as being established in the area as far as the Kura from ca. 800 BC, and they were rivals of Urartu and Assyria, but later fell under the rule of Urartu until their destruction and eventual assimilation by the Medes under Cyaxares in 616 BC. In ancient times, they were mixed with the Persian people who settled in the area during the Achaemenid, Parthian and Sassanid periods.

Cities and regions

Strabo had no knowledge of any city in Albania, although in the first century AD Pliny mentions the initial capital of the kingdom which was pronounced in many different ways including Kabalaka, Shabala, Tabala, and present-day Qabala. Later the capital moved to the south to Partaw (present-day Barda).

Early history

According to the Georgian chronicle “Juansher's Concise History of the Georgians”, Armenians, Georgians and Albanians had one father named Togarmah (Torgom), who was a descendant of Japheth, son of Noah. Torgom divided his land among his sons, and gave to one of them, by the name of Bartos, the "territory from the Berdahoj river to the region of the Kur river to the sea where the conjoined Erasx (Aras) and Kur rivers enter it". According to this legend, Bartos built the city Partaw in his own name.

According to the local tradition, Aran was the legendary ancestor and eponym of the Albanians. Thus, referring to the events in the beginning of the second century BC, he mentions that "… as leader of , by Vagharshak's order, was appointed someone from the family of Sisakan, one of the descendants of Yafet, named Aran, who inherited the plains and mountains of the country of Aghvank beginning from the river Yeraskh (Araks) up to the castle of Hnarakert (on river Kura)," after whom "this country was called Aghvank" (I.4). Medieval historian Moses of Kalankatuyk explained the name Alvank as a derivation from the word Alu which was the nickname of Caucasian Albania's first king Aran and referred to his lenient personality. The Armenian historian Moses of Chorene, who is considered "the father of Armenian history", also confirmed that the Sisakan family inherited the area "from the river Yeraskh (Araks) up to the castle called Hnarakert," and the region was named Aghvank after them in the early 2nd century BC (History of Armenia, II.8). However it is uncertain whether Aran and Sisak were real or imaginary persons.

The kingdom of Caucasian Albania was founded in the late fourth or early third century BC. Albanians are mentioned for the first time in 331 BC at the Battle of Gaugamela as participants from the satrapy of Media.

Parts of Caucasian Albania, including Utik on the right bank of the Kura river were conquered by the Armenians, in the first century BC.

Strabo, Ptolemy and Pliny all write that at this time, the border between Albania and the Kingdom of Greater Armenia was the river Kura. At the same time Strabo writes that the river of Kura flows through Albania. However the frontier along the Kura was repeatedly overrun, to the advantage sometimes of the Albanians, sometimes of the Armenians. In 66 BC, following the defeat of the Armenian king Tigranes II at the hand of the Romans, the Armenian empire lost most of its territory. At this time, the Albanians regained control over their right bank territories conquered by Armenians. According to the seventh-century historian Moses of Kalankatuyk, author of "History of Aghvank", at this time, the southern border of Caucasian Albania was along the Araks river.

In 65 B.C. the Roman general Pompey invaded Albania. When fording the Alazan river, he was attacked by forces of Oroezes, king of Albania, and eventually defeated them. According to Plutarch, Albanians "were led by a brother of the king, named Cosis, who as soon as the fighting was at close quarters, rushed upon Pompey himself and smote him with a javelin on the fold of his breastplate; but Pompey ran him through the body and killed him".

Plutarch also reported that "after the battle, Pompey set out to march to the Caspian Sea, but was turned back by a multitude of deadly reptiles when he was only three days march distant, and withdrew into Lesser Armenia".

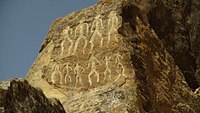

Between 83 and 93 AD, in the reign of the Roman Emperor Domitian a detachment of the Legio XII Fulminata was sent to the Caucasus to support the allied kingdoms of Iberia and Albania in a war against Parthia. An inscription found in Gobustan (69 km south of Baku) attests to the presence of a Roman garrison in that area. During the reign of Roman emperor Hadrian (117-138) Albania was invaded by the Alans, an Iranian nomadic group.

The Sasanian domination

Main article: Albania (satrapy)In 252-253 AD Caucasian Albania along with Iberia and Armenia was conquered by the Sassanid Empire. Albania was mentioned among the Sasanian provinces listed in the trilingual inscription of Shapur I at Naqsh-e Rustam.

In the middle of the fourth century the king of Albania Urnayr arrived in Armenia and was baptized by Gregory the Illuminator, but Christianity spread in Albania only gradually, and the Albanian king remained loyal to the Sassanids. After the partition of Armenia between Byzantium and Persia (in 387 AD), Albania, as an ally of Sassanid Persia, regained all the right bank of the river Kura up to river Araxes, including Artsakh and Utik.

Sasanian king Yazdegerd II passed an edict requiring all the Christians in his empire to convert to Mazdaism, fearing that Christians might ally with Roman Empire, which had recently adopted Christianity. This led to a rebellion of Albanians, along with Armenians and Iberians. In a battle that took place in 451 AD in the Avarayr field, the allied forces of the Armenian, Albanian and Iberian kings, devoted to Christianity, suffered defeat at the hands of the Sassanid army. Many of the Albanian nobility fled to the mountainous regions of Albania, particularly to Artsakh, which became a center for resistance to Sassanid Persia. The religious center of the Albanian state also moved here. However, the Albanian king Vache, a relative of Yazdegerd II, was forced to convert to the official religion of the Sasanian empire, but soon reverted back to Christianity.

In the middle of the fifth century by the order of the Persian king Peroz I Vache built in Utik the city initially called Perozabad, and later Partaw and Barda, and made it the capital of Albania. Partaw was the seat of the Albanian kings and Persian marzban, and in 552 A.D. the seat of the Albanian Catholicos was also transferred to Partaw.

After the death of Vache, Albania remained without a king for thirty years. The Sasanian Balash reestablished the Albanian monarchy by making Vachagan, son of Yazdegerd and brother of the previous king Vache, the king of Albania.

By the end of the fifth century, the ancient Arsacid royal house of Albania, a branch of the ruling dynasty of Parthia, became extinct, and in the sixth century it was replaced by princes of the Persian or Parthian Mihranid family, who claimed descent from the Sasanians. They assumed a Persian title of Arranshah (i.e.the shah of Arran, the Persian name of Albania). The ruling dynasty was named after its Persian founder Mihran, who was a distant relative of the Sasanians. The Mihranid dynasty survived under Muslim suzerainty until 821-2.

In the late sixth – early seventh centuries the territory of Albania became an arena of wars between Sasanian Persia, Byzantium and the Khazar kaganate, the latter two very often acting as allies. In 628, during the Third Perso-Turkic War, the Khazars invaded Albania, and their leader Ziebel declared himself lord of Albania, levying a tax on merchants and the fishermen of the Kura and Araxes rivers "in accordance with the land survey of the kingdom of Persia". Most of Transcaucasia was under Khazar rule before the arrival of the Arabs. The Albanian kings retained their rule by paying tribute to the regional powers. According to Peter Golden, "steady pressure from Turkic nomads was typical of the Khazar era, although there are no unambiguous references to permanent settlements", while Vladimir Minorsky stated that, in Islamic times, "the town of Qabala lying between Sharvan and Shakki was a place where Khazars were probably settled".

Arab and Seljuk domination

Main article: ArranIn the middle of the seventh century, the kingdom was overrun by the Arabs and, like all Islamic conquests at the time, incorporated into the Caliphate. The Albanian king Javanshir, the most prominent ruler of Mihranid dynasty, fought against the Arab invasion of caliph Uthman on the side of the Sasanid Iran. Facing the threat of the Arab invasion on the south and the Khazar offensive on the north, Javanshir had to recognize the Caliph’s suzerainty. The Arabs then reunited the territory with Armenia under one governor.

From the eighth century, Caucasian Albania existed as the principalities of Arranshahs and Khachin, along with various Caucasian, Iranian and Arabic principalities: the Principality of Shaddadids, the Principality of Shirvan, the Principality of Derbent, etc. Most of the region was ruled by the Sajid Dynasty of Azerbaijan from 890 to 929.

As a result of the expansion of Seljuks Turks into the territory of modern Azerbaijan in the eleventh century, the indigenous Albanian population was assimilated. Albanians played a significant role in the ethnogenesis of today's Azeris.

Religion

The ancient pagan religion of Albania was centered on the worship of three divinities, designated by Interpretation Romana Sol, Zeus, and Luna.

Caucasian Albania was one of the first countries where Christianity was adopted in the fourth century, and the first Christian church in the region was built by St. Eliseus, a disciple of Thaddeus of Edessa, in a place called Gis (believed to be the modern-day Church of Kish).

In 498 AD (in other sources, 488 AD) in the settlement named Aluen (Aguen) (present day Agdam region of Azerbaijan), an Albanian church council convened to adopt laws further strengthening the position of Christianity in Albania.

Albanian churchmen took part in missionary efforts in the Caucasus and Pontic regions. In 682, the catholicos, Israel, led an unsuccessful delegation to convert Alp Iluetuer, the ruler of the North Caucasian Huns, to Christianity. The Albanian Church maintained a number of monasteries in the Holy Land.

The Arabic conquest resulted in gradual Islamization of the Albanian population.

Alphabet and language

Main article: Old Udi scriptAccording to Movses Kaghankatvatzi, the Old Udi alphabet was invented by Mesrob Mashdots, an Armenian monk, theologian and linguist

A disciple of Saint Mesrob, Koriun, in "The Life of Mashtots", wrote: "Then there came and visited them an elderly man, an Albanian named Benjamin. And he inquired and examined the barbaric diction of the Albanian language, and then through his usual God-given keenness of mind invented an alphabet, which he, through the grace of Christ, successfully organized and put in order." (see Koriun, Ch. 16).

The Old Udi alphabet of fifty-two letters, some bearing a resemblance to Armenian or Georgian characters, has only survived in a few inscriptions. It was rediscovered by a Georgian scholar, Professor Ilia Abuladze, in 1937. The alphabet was found in Yerevan' Matenadaran, in an Armenian-language manual (No. 7117) of the 15th century. This manual presents different alphabets for comparison: Armenian, Greek, Latin, Syrian, Georgian, Coptic, and Old Udi among them. The alphabet was titled: "Aluanic girn e" (Armenian: Աղվանից գիրն Է, meaning, "Albanian" letters). Abuladze made an assumption that this alphabet was based on Georgian letters. Jost Gippert, professor of Comparative Linguistics at the University of Frankfurt (Main), is preparing an edition of the manuscript.

The distinctive Old Udi speech persisted into early Islamic times, and Muslim geographers Al-Muqaddasi, Ibn-Hawqal and Al-Istakhri recorded that the language which they called Arranian was still spoken in the capital Barda and the rest of the country in the 10th century C.E. The Udi language, spoken by 8000 people mostly in Azerbaijan, and also Georgia, is thought to be the last remnant of the language once spoken in Caucasian Albania.

Footnotes

- ^ V. Minorsky. Caucasica IV. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 15, No. 3. (1953), p. 504

- ^ James Stuart Olson. An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. ISBN 0313274975

- ^ "Arran". Encyclopaeida Iranica. By C.E Bosworth Cite error: The named reference "Bosworth" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Robert H. Hewsen. "Ethno-History and the Armenian Influence upon the Caucasian Albanians," in: Samuelian, Thomas J. (Hg.), Classical Armenian Culture. Influences and Creativity, Chicago: 1982, 27-40.

- Strabo. Geography, book 11, chapter 14.

- ^ Encyclopedia Iranica. M. L. Chaumont. s.v. "Albania'. Cite error: The named reference "Chaumont" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Juansher's Concise History of the Georgians

- The History of Aluank by Moses of Kalankatuyk. Book I, chapter IV

- J. H. Kramers. "The Military Colonization of the Caucasus and Armenia under the Sassanids." Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, Vol. 8, No. 2/3.

- The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. Nagorno-Karabakh

- Russia and Azerbaijan: a borderland in transition, T. Swietochowski

- Plutarch, The Parallel Lives. Pompey, 35

- Plutarch, The Parallel Lives: "Pompey", 36

- Encyclopaedia Britannica 1911, s.v. "Albania, Caucasus".

- Gignoux. "Aneran". Encyclopaedia Iranica: "The high priest Kirder, thirty years later, gave in his inscriptions a more explicit list of the provinces of Aneran, including Armenia, Georgia, Albania, and Balasagan, together with Syria and Asia Minor."

- Encyclopaedia Britannica: "The list of provinces given in the inscription of Ka'be-ye Zardusht defines the extent of the empire under Shapur

- "However Albania retained its monarchy and was designated as a kingdom, and the relationship of the local rulers with the Sasanian “king of kings” is usually referred to by scholars as “vassalage”. Josef Wiesehofer. Ancient Persia. ISBN-10: 1860646751

- Movses Kalankatuatsi. History of Albania. Book 1, Chapter XV

- Movses Kalankatuatsi. History of Albania. Book 2, Chapter VI

- Moses Kalankatuatsi. History of country of Aluank. Chapter XVII. About the tribe of Mihran, hailing from the family of Khosrow the Sasanian, who became the ruler of the country of Aluank

- The Cambridge History of Iran. 1991. ISBN 0521200938

- V.Minorsky. History of Shirvan and Darband.

- An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples by Peter B. Golden. Otto Harrasowitz (1992), ISBN 3-447-03274-X (retrieved 8 June 2006), p. 385–386.

- Movses Kalankatuatsi. History of Albania. Book 2, Chapter LII

- Moses Kalankatuyk, The History of Aluank, I, 27 and III, 24.

- Thomson, Robert W. (1996). Rewriting Caucasian History: The Medieval Armenian Adaptation of the Georgian Chronicles. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198263732.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - http://titus.fkidg1.uni-frankfurt.de/armazi/framee.htm?armaz3m.htm#dProjekt Digitization of the Albanian palimpsest manuscripts from Mt. Sinai

- Caucasian Albanian Script. The Significance of Decipherment by Dr. Zaza Alexidze.

See also

External links

- Encyclopedia Iranica. Albania, Ancient country in Caucasus, by M. Chaumont

- About the Caucasian Albania

- About the Caucasian Albania (section 10)

- Wolfgang Schulze (Munich): Caucasian Albanian

References

- Template:Ru icon Movses Kalankatuatsi. The History of Aluank. Translated from Old Armenian (Grabar) by Sh.V.Smbatian, Yerevan, 1984.

- Template:En icon Koriun, The Life of Mashtots, translated from Old Armenian (Grabar) by Bedros Norehad.

- Template:Ge icon Movses Kalankatuatsi. History of Albania. Translated by L. Davlianidze-Tatishvili, Tbilisi, 1985.

- Template:Ru icon Movses Khorenatsi. The History of Armenia. Translated from Old Armenian (Grabar) by Gagik Sargsyan, Yerevan, 1990.

- Template:En icon Ilia Abuladze. About the discovery of the alphabet of the Caucasian Albanians. - "Bulletin of the Institute of Language, History and Material Culture (ENIMK)", Vol. 4, Ch. I, Tbilisi, 1938.

| Provinces of the Sasanian Empire | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| * indicates short living provinces | ||