| Revision as of 13:37, 17 July 2008 editMindmatrix (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators187,395 editsm Reverted edits by 70.69.184.92 (talk) to last version by Tj9991← Previous edit | Revision as of 03:27, 6 August 2008 edit undoRet.Prof (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers15,357 edits →Internal and external influences leading to ConfederationNext edit → | ||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

| External pressures that influenced Confederation: | External pressures that influenced Confederation: | ||

| * the U.S. doctrine of ], the constant threat of intervention from the US | * the U.S. doctrine of ], the real and constant threat of intervention from the US | ||

| * the ], British actions and American reactions | * the ], British actions and American reactions | ||

| * the ] | * the ] | ||

Revision as of 03:27, 6 August 2008

Canadian Confederation was the process by which the federal Dominion of Canada was formed beginning 1 July 1867 from the provinces, colonies and territories of British North America.

Usage

In terms of political structure, Canada is a federal state and not a confederate association of sovereign states. However, Canada is often considered—in addition to Switzerland, whose official name in English is the Swiss Confederation—to be among the world's most decentralized federations.

In a Canadian context, Confederation generally describes the political process that united the colonies in the 1860s and related events, and the subsequent incorporation of other colonies and territories. The term Confederation is now often used to describe Canada in an abstract way, "the Fathers of Confederation" itself being one such usage. Provinces and territories that became part of Canada after 1867 are also said to have joined, or entered into, Confederation (but not the Confederation).

The term is also used to divide Canadian history into pre-Confederation (i.e. pre-1867) and post-Confederation (i.e. post-1867) periods, the latter of which includes current events.

History and process

Colonial organization

All the colonies which would become involved in Canadian Confederation in 1867 were initially part of New France and were ruled by France. The British Empire’s first acquisition in what would become Canada was Acadia, acquired by the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht (though the Acadian population retained loyalty to New France, and was eventually expelled by the British in the 1755 Great Upheaval). The British renamed Acadia Nova Scotia. The rest of New France was acquired by the British Empire by the Treaty of Paris (1763), which ended the Seven Years' War. Most of New France became the Province of Quebec, while present-day New Brunswick was annexed to Nova Scotia. In 1769, present-day Prince Edward Island, which had been a part of Acadia, was renamed “St John’s Island” and organized as a separate colony (it was renamed PEI in 1798 in honour of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn).

In the wake of the American Revolution, approximately 50,000 United Empire Loyalists fled to British North America. The Loyalists were unwelcome in Nova Scotia, so the British created the separate colony of New Brunswick for them in 1784. Most of the Loyalists settled in the Province of Quebec, which in 1791 was separated into a predominantly-English Upper Canada and a predominantly-French Lower Canada by the Constitutional Act of 1791.

Following the Rebellions of 1837, Lord Durham in his famous Report on the Affairs of British North America, recommended that Upper Canada and Lower Canada should be joined to form the Province of Canada and that the new province should have responsible government. As a result of Durham’s report, the British Parliament passed the Act of Union 1840, and the Province of Canada was formed in 1841. The new province was divided into two parts: Canada West (the former Upper Canada) and Canada East (the former Lower Canada). Ministerial responsibility was finally granted by Governor General Lord Elgin in 1848, first to Nova Scotia and then to Canada. In the following years, the British would extend responsible government to Prince Edward Island (1851), New Brunswick (1854), and Newfoundland (1855).

The remainder of modern-day Canada was made up of Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory (both of which were controlled by the Hudson's Bay Company and ceded to Canada in 1870) and the Arctic Islands, which were under direct British control and became part of Canada in 1880. The area which constitutes modern-day British Columbia was the separate Colony of British Columbia (formed in 1858, in an area where the Crown had previously granted a monopoly to the Hudson's Bay Company), with the Colony of Vancouver Island (formed 1849) constituting a separate crown colony until its absorption by the Colony of British Columbia in 1866.

Early projects

The idea of a legislative union of all British colonies in America goes back to at least 1754, when the Albany Congress was held, preceding the Continental Congress of 1774. At least twelve other projects followed. These, however, did not include the colonies that were located in the territory of present-day Canada.

The idea was revived in 1839 by Lord Durham in his Report on the Affairs of British North America.

In 1857, Joseph-Charles Taché proposed a federation in the Courrier du Canada.

In 1858, Alexander Tilloch Galt, George-Étienne Cartier and John Ross travelled to Great Britain to present the British Parliament with a project for confederation of the British colonies. The proposal was received by the London authorities with polite indifference.

By 1864, it was clear that continued governance of the Province of Canada under the terms of the 1840 Act of Union had become impracticable. Therefore, a Great Coalition of parties formed in order to reform the political system.

Internal and external influences leading to Confederation

There were several factors that influenced Confederation, both caused from internal sources and pressures from external sources.

Internal causes that influenced Confederation:

- between 1854 and 1865 the United States followed a policy of free trade (the Canadian-American Reciprocity Treaty) where products were allowed into their country without taxes or tariffs; in 1865, the United States canceled reciprocity

- political deadlock resulting from the current political structure

- demographic pressure

- economic nationalism and the promise of economic development

External pressures that influenced Confederation:

- the U.S. doctrine of Manifest destiny, the real and constant threat of intervention from the US

- the U.S. Civil war, British actions and American reactions

- the Fenian raids

- the creation of a new British colonial policy, whereby Britain no longer wanted to maintain troops in its colonies.

The Charlottetown Conference, September 1–9, 1864

Main article: Charlottetown ConferenceIn the spring of 1864, New Brunswick premier Samuel Leonard Tilley, Nova Scotia premier Charles Tupper, and Prince Edward Island premier John Hamilton Gray were contemplating the idea of a Maritime Union which would join their three colonies together.

The Premier of the Province of Canada John A. Macdonald surprised the Atlantic premiers by asking if the Province of Canada could be included in the negotiations. After several years of legislative paralysis in the Province of Canada caused by the need to maintain a double legislative majority (a majority of both the Canada East and Canada West delegates in the Province of Canada’s legislature), Macdonald had led his Liberal-Conservative Party into the Great Coalition with George-Étienne Cartier’s Parti bleu and George Brown’s Clear Grits. Macdonald, Cartier, and Brown felt that union with the other British colonies might be a way to solve the political problems of the Province of Canada.

The Charlottetown Conference began on September 1, 1864. Since the agenda for the meeting had already been set, the delegation from the Province of Canada was initially not an official part of the Conference. They were allowed to address the Conference, however, and were soon formally invited to join the Conference.

No minutes from the Charlottetown Conference survive, but we do know that George-Étienne Cartier and John A. Macdonald presented arguments in favour of a union of the four colonies; Alexander Tilloch Galt presented the Province of Canada’s proposals on the financial arrangements of such a union; and that George Brown presented a proposal for what form a united government might take. The Canadian delegation’s proposal for the governmental system involved:

- preservation of ties with Great Britain;

- residual jurisdiction left to a central authority;

- a bicameral system including a Lower House with representation by population (rep by pop) and an Upper House with representation based on regional, rather than provincial, equality;

- responsible government at the federal and provincial levels; and

- the appointment of a governor general by the British Crown.

After the Conference adjourned on September 9, there were further meetings between delegates held at Halifax, Saint John, and Fredericton. These meetings evinced enough interest that it was decided to hold a second Conference.

The Quebec Conference, October 10–27, 1864

Main article: Quebec Conference, 1864

After returning home from the Charlottetown Conference, John A. Macdonald asked Viscount Monck, the Governor General of the Province of Canada to invite delegates from the three Maritime provinces and Newfoundland to a conference with United Canada delegates. Monck obliged and the Conference went ahead at Quebec City in October.

The Conference began on October 10, 1864 on the site of the present-day Château Frontenac. The Conference elected Étienne-Paschal Taché as its chairman, but it was dominated by Macdonald.

At the end of the Conference, it adopted the Seventy-two Resolutions which would form the basis of a scheduled future conference. The Conference adjourned on October 27.

The London Conference, December 1866–March 1867

Main article: London Conference of 1866Following the Quebec Conference, the Province of Canada’s legislature passed a bill approving the union. The union proved more controversial in the Maritime provinces, however, and it was not until 1866 that New Brunswick and Nova Scotia passed union resolutions. (At this point, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland opted against union.)

Sixteen delegates from the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia traveled to London in December 1866. At meetings held at the Westminster Palace Hotel, the delegates reviewed the Seventy-two Resolutions. Although Charles Tupper had promised anti-union forces in Nova Scotia that he would push for amendments, he was unsuccessful in getting amendments passed. The Conference approved the 72 Resolutions, which now became the “London Resolutions” and passed them on to the British Colonial Office.

After breaking for Christmas, the delegates reconvened in January 1867 and began drafting the British North America Act. They easily agreed that the new country should be called “Canada”, that Canada East should be renamed “Quebec” and that Canada West should be renamed “Ontario.” There was, however, heated debate about how the new country should be designated. Ultimately, the delegates elected to call the new country the Dominion of Canada, after "kingdom" and "confederation", among other options, were rejected for various reasons. The term "dominion" originates from Psalm 72:8 (KJV) and was (allegedly) suggested by Sir Samuel Leonard Tilley.

The delegates had completed their draft of the British North America Act by February 1867. The Act was presented to Queen Victoria on February 11, 1867. The bill was introduced in the House of Lords the next day. The bill was quickly approved by the House of Lords, and then also quickly approved by the British House of Commons. (The Conservative Lord Derby was prime minister of the United Kingdom at the time.) The Act received royal assent on March 29, 1867 and set July 1, 1867 as the date for union.

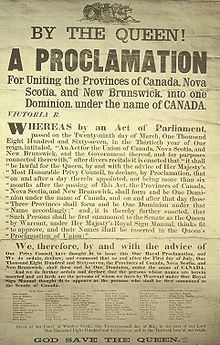

British North America Act, 1867

Confederation was accomplished when Queen Victoria gave royal assent to the British North America Act (BNA Act) on March 29, 1867. That act, which united the Province of Canada with the colonies of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, came into effect on July 1 that year. The act replaced the Act of Union (1840) which had previously unified Upper Canada and Lower Canada into the united Province of Canada. Separate provinces were re-established under their current names of Ontario and Quebec. July 1 is now celebrated as Canada Day.

The form of the country's government was influenced by the American republic to the south. Noting the flaws perceived in the American system, the Fathers of Confederation opted to retain a monarchical form of government. John A. Macdonald, speaking in 1865 about the proposals for the upcoming confederation of Canada, said:

By adhering to the monarchical principle we avoid one defect inherent in the Constitution of the United States. By the election of the president by a majority and for a short period, he never is the sovereign and chief of the nation. He is never looked up to by the whole people as the head and front of the nation. He is at best but the successful leader of a party. This defect is all the greater on account of the practice of reelection. During his first term of office he is employed in taking steps to secure his own reelection, and for his party a continuance of power. We avoid this by adhering to the monarchical principle—the sovereign whom you respect and love. I believe that it is of the utmost importance to have that principle recognized so that we shall have a sovereign who is placed above the region of party—to whom all parties look up; who is not elevated by the action of one party nor depressed by the action of another; who is the common head and sovereign of all.

While the BNA Act gave Canada more autonomy than it had before, it was far from full independence from the United Kingdom. Foreign policy remained in British hands, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council remained Canada's highest court of appeal, and the constitution could be amended only in Britain. Gradually, Canada gained more autonomy, and in 1931, obtained almost full autonomy within the British Commonwealth with the Statute of Westminster. Because the provinces of Canada were unable to agree on a constitutional amending formula, this power remained with the British Parliament. In 1982, the constitution was patriated when Queen Elizabeth II gave her royal assent to the Canada Act 1982. The Constitution of Canada is made up of a number of codified acts and uncodified traditions; one of the principal documents is the Constitution Act, 1982, which renamed the BNA Act 1867 to Constitution Act, 1867.

Aftermath of Confederation, July 1, 1867

Dominion elections were held in August and September to elect the first Parliament, and the four new provinces' governments recommended the 72 individuals (24 each for Quebec and Ontario, 12 each for New Brunswick and Nova Scotia) who would sit in the Senate.

Fathers of Confederation

The following lists the participants in the Charlottetown, Quebec, and London Conferences and their attendance at each stage. They are known as the Fathers of Confederation.

There were 36 original Fathers of Confederation. Harry Bernard, who was the recording secretary at the Charlottetown Conference, is considered by some to be a Father of Confederation. The later "Fathers" who brought the other provinces into Confederation after 1867 are also referred to as "Fathers of Confederation." In this way, Amor De Cosmos who was instrumental both in bringing democracy to British Columbia and in bringing his province into Confederation, is considered by many to be a Father of Confederation. As well, Joey Smallwood is popularly referred to as "the Last Father of Confederation", because he led Newfoundland into Confederation in 1949.

More controversially, there is also a movement to have Louis Riel accepted as a Father of Confederation for his role in bringing Manitoba into Confederation following the Red River Rebellion of 1869–1870, even though Riel was later executed for treason following the North-West Rebellion of 1885.

Table of participation

Joining Confederation

- See also: History of Canada

After the initial Act of Union in 1867, Manitoba was established by an Act of Parliament on July 15, 1870, originally as an area much smaller than the current province. British Columbia joined Canada July 20, 1871, by Act of Parliament (and encouraged to join by Sir John A. Macdonald's promise of a railway within 10 years). Prince Edward Island joined July 1, 1873 (and, as part of the terms of union, was guaranteed a ferry link, a term which was deleted upon completion of the Confederation Bridge in 1997). Alberta and Saskatchewan were established September 1, 1905, by Acts of Parliament. Newfoundland joined on March 31, 1949, also with a ferry link guaranteed.

The Dominion acquired Rupert's Land from the Hudson's Bay Company and the North-Western Territory from the Crown in 1869, and took ownership on December 1 of that year, merging them and naming them North-West Territories (though final payment to the Hudson's Bay Company did not occur until 1870). In 1880, the British assigned all North American Arctic islands to Canada, right up to Ellesmere Island. From this vast swath of territory were created three provinces (Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta) and two territories (Yukon and North-West Territories), and two extensions each to Quebec, Ontario, and Manitoba. Later the Territory of Nunavut was also created.

List of provinces and territories in order of entering Confederation

Below is a list of Canadian provinces and territories in the order in which they entered Confederation; territories are italicized. At formal events, representatives of the provinces and territories take precedence according to this ordering, except that provinces always precede territories. For provinces that entered on the same date, the order of precedence is based on the provinces' populations at the time they entered Confederation.

| Order | Date | Name |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 July 1867 | |

| 5 | 15 July 1870 | |

| 7 | 20 July 1871 | |

| 8 | 1 July 1873 | |

| 9 | 13 June 1898 | |

| 10 | 1 September 1905 | |

| 12 | 31 March 1949 | |

| 13 | 1 April 1999 |

In 1870 the Hudson's Bay Company-controlled Rupert's Land and North-Western Territory were transferred to the Dominion of Canada. Most of these lands were formed into a new territory named Northwest Territories, but the region around Fort Garry was simultaneously established as the province of Manitoba by the Manitoba Act of 1870. Manitoba later received additional land from the Northwest Territories, and Yukon, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Nunavut were later created out of the Northwest Territories. The remaining provinces joined Canada as separate and previously independent colonies.

References

- Collaborative Federalism in an era of globalization"

- Macdonald, John A.; On Canadian Confederation; 1865

External links

- Library and Archives Canada

- Bibliothèque et Archives Canada

- Library Search, Library and Archives Canada—"Confederation"

- Online Archives Search, Library and Archives Canada—"Confederation"

- Website Search, Library and Archives Canada—"Confederation"

- Résultat de documents de bibliothèques, Bibliothèque et Archives Canada—"Pères de la Confédération"

- Résultats du site Web, Bibliothèque et Archives Canada—"Pères de la Confédération"

- Conference at Québec in 1864, to settle the basics of a union of the British North American Provinces. Copy of a painting by Robert Harris, 1885—Archives, Library and Archives Canada

- Conférence à Québec, en 1864, pour établir les bases d'une union des provinces de l'Amérique du Nord britannique. Copie d'une peinture de Robert Harris, 1885.—Pièce (reliée)—d’archives, Bibliothèque et Archives Canada