| Revision as of 22:32, 8 October 2005 editBobblewik (talk | contribs)66,026 editsm sentence case← Previous edit | Revision as of 03:20, 14 October 2005 edit undoKusma (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators59,820 editsm period in minutes (not meters)Next edit → | ||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

| |'''Perigee:<br>(1st orbit)'''||158.8 km | |'''Perigee:<br>(1st orbit)'''||158.8 km | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| |'''Period:<br>(1st orbit)'''||88.78 |

|'''Period:<br>(1st orbit)'''||88.78 min | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| |'''Inclination:'''||28.91 deg | |'''Inclination:'''||28.91 deg | ||

| Line 144: | Line 144: | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| |Period | |Period | ||

| |90.5 |

|90.5 min | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| |Inclination | |Inclination | ||

Revision as of 03:20, 14 October 2005

| Mission insignia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mission statistics | |

| Mission name: | Gemini 9A |

| Call sign: | Gemini 9A |

| Number of crew: |

2 |

| Launch: | June 3, 1966 13:39:33.335 UTC Cape Canaveral LC 19 |

| Landing: | June 6, 1966 14:00:23 UTC 27°52′N 75°0.4′W / 27.867°N 75.0067°W / 27.867; -75.0067 |

| Duration: | 3 days, 0 hours 20 minutes 50 seconds |

| Distance traveled: | ~2,020,741 km |

| Orbits: | 47 |

| Apogee: (1st orbit) |

266.9 km |

| Perigee: (1st orbit) |

158.8 km |

| Period: (1st orbit) |

88.78 min |

| Inclination: | 28.91 deg |

| Mass: | 3,750 kg |

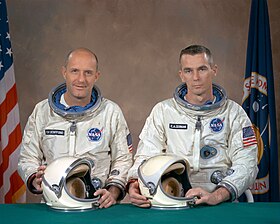

| Crew picture | |

Gemini 9A crew portrait (L-R: Stafford, Cernan) | |

| Gemini 9A crew | |

Gemini 9A (officially Gemini IX-A) was a 1966 manned spaceflight in NASA's Gemini program. It was the 7th manned Gemini flight, the 13th manned American flight and the 23rd spaceflight of all time (includes X-15 flights over 100 km).

Crew

- Thomas Stafford (flew on Gemini 6A, Gemini 9A, Apollo 10, & Apollo-Soyuz), Command Pilot

- Eugene Cernan (flew on Gemini 9A, Apollo 10, & Apollo 17), Pilot

Backup crew

- James A. Lovell, Jr, Command Pilot

- Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr., Pilot

Mission parameters

- Mass: 3,750 kg

- Perigee: 158.8 km

- Apogee: 266.9 km

- Inclination: 28.91°

- Period: 88.78 min

1st rendezvous

Space walk

- Cernan

See also

Elliott See, Charles Bassett; and backup crew

(back row, L-R) Tom Stafford, Gene Cernan (NASA)

The original prime crew for Gemini IX was Elliott See (Command Pilot) and Charles Bassett (Pilot). However See and Bassett were both killed when their plane crashed into a McDonnell aircraft hangar in St. Louis on February 28, 1966. Ironically, the hangar was the very building where the Gemini IX spacecraft was being built. The backup crew of Stafford and Cernan was promoted to the prime crew, while a new backup crew was created from the crew originally assigned to backup Gemini XI. This latter fact is significant as the standard crew rotation meant that a spot on the backup crew of Gemini XI would have placed Buzz Aldrin on the prime crew of the non-existent Gemini XIV. (The crew rotation usually meant that after serving on a backup crew, you could expect to skip two missions and then be on a prime crew.) Being moved up to the backup crew of Gemini IX meant that Aldrin flew prime crew on Gemini XII and played a major part in his selection for the Apollo 8 backup and Apollo 11 prime crews - a crew place which ultimately made him the second man on the moon.

Objectives

Stafford and Cernan became the first backup crew to fly in space after the first crew of Elliott See and Charles Bassett died in a plane crash four months before the flight. They were to dock with an Agena like the Gemini 8 mission, but during launch of the Gemini 9 Agena on May 17, 1966, its Atlas booster malfunctioned and it failed to make it to orbit. On June 1, 1966 a substitute for the Agena was launched in the form of the ATDA (Augmented Target Docking Adapter). Basically the ATDA is the forward docking section of an Agena without the rear fuel tank and rocket engine. The highlight of the mission was to have been a docking with the ATDA. The docking was canceled, though, after Stafford and Cernan rendezvoused with the target to find its protective shroud still attached over the docking port, which made it look, in Stafford's words, like an "angry alligator." Cernan also was to have tested an Astronaut Maneuvering Unit (AMU) a jet-powered backpack stowed outside in Gemini's adapter module, to which the spacewalking astronaut was to have strapped himself. But Cernan's spacewalk was troubled from the start. His visor fogged, he sweated and struggled with his tasks, and he had problems moving in microgravity. Everything took longer than expected, and Cernan had to go inside before getting a chance to fly the AMU. The device was not finally tested in space until Skylab, seven years later.

The original Gemini 9 mission was intended to be a repeat of the shortened Gemini 8 mission. The crew would dock with an Agena Target Vehicle and perform an EVA. But once again the Agena caused problems like it had on Gemini 6A. Once again the Agena exploded during launch, but this time there was an alternative.

The augmented target docking adapter or the ATDA had been designed and built by McDonnell, the manufacturers of the Gemini spacecraft. It was basically a short cylinder with a docking cone on the front. It had all the systems that the Gemini would need for rendezvous but lacked a propulsion unit. It was built using already tested equipment and launched using the Atlas-SLV3 rocket.

As well as the docking there was also a planned EVA by Cernan. The plan was for him to move to the rear of the spacecraft and strap himself into the Air Force's Astronaut Maneuvering Unit (AMU). This was the first 'rocket pack' and a predecessor of the Manned Maneuvering Unit used by Shuttle astronauts in the 1980s. It had its own propulsion, stabilization system, oxygen and telemetry for the biomedical data and systems. It used hydrogen peroxide for propellant.

Flight

Launch attempts

The first launch attempt of Gemini 9A was on June 1. The ATDA had launched perfectly into a 298 kilometre orbit, though telemetry from it indicated that the launched shroud had failed to open properly. But the Gemini spacecraft was not able to launch the same day as planned. At T-3 minutes, the ground computers could not contact the Gemini computers for some reason and the 40 second launch window opened and closed without the launch.

The second launch attempt went perfectly with the spacecraft entering into orbit. With this launch, Stafford could say that he had been strapped into a spacecraft six times ready for launch.

| Gemini 9 | Agena & ATDA |

|---|---|

| Agena | GATV-5004 |

| Mass | 3,252 kg |

| Launch site | LC-14 |

| Launch date | May 17, 1966 |

| Launch time | 15:12 UTC |

| Destroyed | 15:19 UTC |

| ATDA | #02186 |

| NSSDC ID: | 1966-046A |

| Mass | 794 kg |

| Launch site | LC-14 |

| Launch date | June 1, 1966 |

| Launch time | 15:00:02 UTC |

| 1st perigee | 298.4 km |

| 1st apogee | 309.7 km |

| Period | 90.5 min |

| Inclination | 28.87 |

| Reentered | June 11, 1966 |

Rendezvous

Their first burn was 49 minutes after launch. They added 22.7 metres per second to their speed which put them in a 160 to 232 kilometres orbit. Their next burn was designed to correct phase, height, and out-of-plane errors. They pointed the spacecraft 40° down, and 3° to the 'left'. The burn added 16.2 metres per second to their speed and put them in a 274 by 276 kilometres orbit, closing at 38 metres per second on the ATDA.

The first radar readings were when they were 240 km away and they had a solid lock at 222 km. Their first sight came 3 hours and 20 minutes into the mission when they were 93 km way. They noted that they could see the flashing lights on the ATDA designed to aid identification from a distance. This made them hope that the launch shroud had in fact been jettisoned and that the telemetry was wrong.

As they got closer they found that in fact the shroud had half come off. Stafford described "It looks like an angry alligator out here rotating around". He asked if maybe he could use the spacecraft to open the 'jaws' but the ground decided against it.

The crew described that the shrouds explosive bolts had fired but a two neatly taped lanyards were holding the shroud together. It was decided that it would be too dangerous for an astronaut to cut the lines, as there were too many sharp edges around.

The reason for the laynards was soon discovered. Douglas built the shroud, but Lockheed attached it to the rocket, while McDonnell built the ATDA. A Douglas engineer had made a practise run with the McDonnell crew but didn't give them instructions on the final procedures which involved the laynards. The McDonnell crew had the Douglas instructions for this procedure which said, "See blueprint", but there was no blueprint. So the McDonnell technicians decided to tape down the loose laynards as it seemed like the sensible thing to do.

The crew then did some planned rendezvous practice that involved them moving away from the ATDA by firing their thrusters and then practising approaching from below the target. They then got some much needed food and rest.

On the second day of the mission, they again approached the ATDA, this time from above. Once they were stationkeeping along side, they were given permission for their EVA. But they were tired and Stafford didn't want to waste fuel keeping himself near the ATDA during the EVA when there was little they could do with it. So it was decided to postpone the EVA until the third day.

EVA

On this third day, the second ever EVA by an American started at just after orbital sunrise. It was planned that Cernan would spend 167 minutes outside the spacecraft--twice around the world.

Cernan found the going tough. Every movement that he made caused a reaction, and even though there were handholds installed on the spacecraft after the comments of Ed White after his EVA on Gemini 4, Cernan found it hard to control himself. Even the umbilical was annoying and hard to control.

He finally reached the rear of the spacecraft and began to check and prepare the AMU. This took longer than planned due to lack of hand and foot holds. He was unable to get any leverage which made it hard to turn valves or basically anything that involved moving. All this was made worse when after sunset, his faceplate fogged up. Due to the difficulties, his pulse soared to about 195 beats per miniute. Doctors on the ground feared he would pass out.

At this point Cernan decided that there was a lot of risk in continuing the EVA. He couldn't see very well and had found that he could not move very well. He would have to disconnect himself from the umbilical that attach him to the Gemini (though would still be attached by a longer thinner lead), after he had connected himself to the AMU. But when he had finished with the AMU he would somehow have to take the thing off with one hand, while the other held onto the spacecraft. So he decided to cancel the rest of the EVA, with Stafford and Mission Control concurring.

He managed to move himself back to the cockpit and Stafford held onto he legs to give a rest. After trying to remove a mirror mounted to the side of the spacecraft, his suit cooling system overheated and his faceplate fogged up completely, meaning he couldn't see. He and Stafford managed to get the hatch closed and repressurised. Cernan had spent 128 minutes outside the spacecraft.

Stafford has said in a 2001 interview that there was a real concern that Cernan would not be able to get back into the capsule. As it would not have been acceptable for Stafford to cut Cernan loose in orbit he stated that the plan was to make re-entry with the astronaut still attached by his umbilical.

As well as the rendezvous and EVA, the other major objective of the mission was to carry out seven experiments. The only medical experiment was M-5, which measured the astronauts reactions to stress by measuring the intake and output of fluids before, during and after the flight.

Experiments

There were two photography experiments. S-1 hoped to image the Zodiacal light during a EVA, but this was changed to inside the spacecraft after the problems encoutered by Cernan. And S-11 involved the astronauts trying to image the Earth's airglow in the atomic oxygen and sodium light spectra. They took 44 pictures as part of this experiment with three being of actual airglow.

S-10 had hoped to retrieve a Micrometeorite Collector from the ATDA, though this failed after they were unable to dock with it. They were able to image it though during their close approaches. Instead they were able to recover the collector from the Gemini spacecraft (S-12). D-12 also failed as it was an investigation of controlling the AMU.

The last experiment was D-14 which was UHF/VHF Polarization. This was an extendable antenna mounted on the adapter section at the rear of the spacecraft. It was hoped to obtain information about communication through the ionosphere. Six trials of this were performed but the antenna was broken by Cernan during his EVA.

Reentry

The day of the EVA was also their last in space. On their 45th revolution of the Earth, they fired the retrofire rockets that slowed them down so that they would reenter. This time the computer worked perfectly, meaning they landed only 700 metres from the planned landing site and were close enough to see the prime recovery ship, the USS Wasp.

After the mission it was decided to set up a Mission Review committee. Their job was to make sure that the objectives planned for each mission were realistic and whether they had a direct benefit for Apollo.

The Gemini 9A mission was supported by the following U.S. Department of Defense resources; 11,301 personnel, 92 aircraft and 15 ships.

Insignia

The Gemini 9 patch is quite simple. It is in the shape of a shield and shows the Gemini spacecraft docked to the Agena. There is a spacewalking astronaut, with his tether forming the shape of a number 9. Although the Gemini 9 mission was changed so that it docked with the ATDA, the patch was not changed. It is also not known whether Bassett and See had designed a patch for the mission as the original crew.

Capsule location

The capsule is on display at the KSC Visitors Center, Kennedy Space Center, Florida.

External links

- On The Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini: http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4203/cover.htm

- Spaceflight Mission Patches: http://www.genedorr.com/patches/Intro.html

- Buy the AMU trainer: http://www.collectspace.com/buyspace/artifacts-gemini.html

- http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/database/MasterCatalog?sc=1966-047A

- U.S. Space Objects Registry http://usspaceobjectsregistry.state.gov/search/index.cfm

| Missions of Project Gemini | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||