| Revision as of 00:35, 15 February 2009 editChyranandChloe (talk | contribs)Rollbackers4,354 edits rnm in the Health effects section, and merges see discussion; remaining section titles have been renamed to be shorter and more effective← Previous edit | Revision as of 00:46, 15 February 2009 edit undoChyranandChloe (talk | contribs)Rollbackers4,354 edits more cleanup; Note: resection according to related subjectsNext edit → | ||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

| === Historical link === | === Historical link === | ||

| As the use of tobacco became popular in Europe, a number of people became concerned about its negative effects. One of the first was King James I of Great Britain. In his 1604 treatise, ], King James observed that smoking was: | |||

| <blockquote>A custome lothsome to the eye, hatefull to the Nose, harmfull to the braine, dangerous to the Lungs, and in the blacke stinking fume thereof, nearest resembling the horrible Stigian smoke of the pit that is bottomelesse.</blockquote> | |||

| The late-19th century invention of automated cigarette-making machinery in the American South made possible mass production of cigarettes at low cost, and cigarettes became elegant and fashionable among society men as the Victorian era gave way to the Edwardian. In 1912, American Dr. Isaac Adler was the first to strongly suggest that lung ] is related to smoking.<ref>Isaac Adler. "Primary Malignant Growth of the Lung and Bronchi". (1912) New York, Longmans, Green. pp. 3-12. by ''A Cancer Journal for Clinicians'' </ref> In 1929, Fritz Lickint of ], ], published a formal statistical evidence of a lung cancer–tobacco link, based on a study showing that ] sufferers were likely to be smokers.<ref name=about_lickint></ref> Lickint also argued that tobacco use was the best way to explain the fact that lung cancer struck men four or five times more often than women (since women smoked much less).<ref name=about_lickint /> | The late-19th century invention of automated cigarette-making machinery in the American South made possible mass production of cigarettes at low cost, and cigarettes became elegant and fashionable among society men as the Victorian era gave way to the Edwardian. In 1912, American Dr. Isaac Adler was the first to strongly suggest that lung ] is related to smoking.<ref>Isaac Adler. "Primary Malignant Growth of the Lung and Bronchi". (1912) New York, Longmans, Green. pp. 3-12. by ''A Cancer Journal for Clinicians'' </ref> In 1929, Fritz Lickint of ], ], published a formal statistical evidence of a lung cancer–tobacco link, based on a study showing that ] sufferers were likely to be smokers.<ref name=about_lickint></ref> Lickint also argued that tobacco use was the best way to explain the fact that lung cancer struck men four or five times more often than women (since women smoked much less).<ref name=about_lickint /> | ||

| Line 253: | Line 257: | ||

| A number of studies have been conducted to explore the relationship between tobacco and other drug use. While the association between smoking tobacco and other drug use has been well-established, the nature of this association remains unclear. The two main theories are the ] (gateway) model and the correlated liabilities model. The causation model argues that smoking is a primary influence on future drug use, while the correlated liabilities model argues that smoking and other drug use are predicated on genetic or environmental factors. | A number of studies have been conducted to explore the relationship between tobacco and other drug use. While the association between smoking tobacco and other drug use has been well-established, the nature of this association remains unclear. The two main theories are the ] (gateway) model and the correlated liabilities model. The causation model argues that smoking is a primary influence on future drug use, while the correlated liabilities model argues that smoking and other drug use are predicated on genetic or environmental factors. | ||

| === |

=== Projecting an image === | ||

| Famous smokers of the past used cigarettes or pipes as part of their image, such as ]'s ]-brand cigarettes, ]'s, ]'s, ]'s, ]'s, and Bing Crosby's pipes, or the news broadcaster ]'s cigarette. Writers in particular seemed to be known for smoking; see, for example, Cornell Professor ]'s book ''Cigarettes are Sublime'' for the analysis, by this professor of French literature, of the role smoking plays in 19th and 20th century letters. The popular author ] addressed his addiction to cigarettes within his novels. British Prime Minister ] was well known for smoking a pipe in public as was ] for his cigars. ], the fictional detective created by ] smoked a pipe, cigarettes, and cigars, besides injecting himself with cocaine, "to keep his overactive brain occupied during the dull London days, when nothing happened". The ] ] comic book character, ], created by ], is synonymous with smoking, so much so that the first storyline by ] creator, ], centred around John Constantine contracting lung cancer. ] ], while ] as "The Sandman", is a chronic smoker in order to appear "tough". | Famous smokers of the past used cigarettes or pipes as part of their image, such as ]'s ]-brand cigarettes, ]'s, ]'s, ]'s, ]'s, and Bing Crosby's pipes, or the news broadcaster ]'s cigarette. Writers in particular seemed to be known for smoking; see, for example, Cornell Professor ]'s book ''Cigarettes are Sublime'' for the analysis, by this professor of French literature, of the role smoking plays in 19th and 20th century letters. The popular author ] addressed his addiction to cigarettes within his novels. British Prime Minister ] was well known for smoking a pipe in public as was ] for his cigars. ], the fictional detective created by ] smoked a pipe, cigarettes, and cigars, besides injecting himself with cocaine, "to keep his overactive brain occupied during the dull London days, when nothing happened". The ] ] comic book character, ], created by ], is synonymous with smoking, so much so that the first storyline by ] creator, ], centred around John Constantine contracting lung cancer. ] ], while ] as "The Sandman", is a chronic smoker in order to appear "tough". | ||

| Line 340: | Line 344: | ||

| Peer support can be helpful, such as that provided by support groups and telephone quitlines. | Peer support can be helpful, such as that provided by support groups and telephone quitlines. | ||

| == Restrictions == | |||

| == Governmental restirctions == | |||

| On February 27, 2005 the ], took effect. The FCTC is the world's first public health treaty. Countries that sign on as parties agree to a set of common goals, minimum standards for tobacco control policy, and to cooperate in dealing with cross-border challenges such as cigarette smuggling. Currently the WHO declares that 4 billion people will be covered by the treaty, which includes 168 signatories.<ref></ref> Among other steps, signatories are to put together legislation that will eliminate secondhand smoke in indoor workplaces, public transport, indoor public places and, as appropriate, other public places. | On February 27, 2005 the ], took effect. The FCTC is the world's first public health treaty. Countries that sign on as parties agree to a set of common goals, minimum standards for tobacco control policy, and to cooperate in dealing with cross-border challenges such as cigarette smuggling. Currently the WHO declares that 4 billion people will be covered by the treaty, which includes 168 signatories.<ref></ref> Among other steps, signatories are to put together legislation that will eliminate secondhand smoke in indoor workplaces, public transport, indoor public places and, as appropriate, other public places. | ||

| === Age |

=== Age === | ||

| Many countries have a ], In many countries, including the United States, most European Union member states, New Zealand, Canada, South Africa, Israel, India, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica and Australia, it is illegal to sell tobacco products to minors and in the Netherlands, Austria, Belgium, Denmark and South Africa it is illegal to sell tobacco products to people under the age of 16. On September 1, 2007 the minimum age to buy tobacco products in ] rose from 16 to 18, as well as in ] where on October 1, 2007 it rose from 16 to 18.<ref></ref> In 46 of the 50 United States, the minimum age is 18, except for Alabama, Alaska, New Jersey, and Utah where the legal age is 19 (also in Onondaga County in upstate New York, as well as Suffolk and Nassau Counties of Long Island, New York).{{Fact|date=July 2007}} Some countries have also legislated against giving tobacco products to (i.e. buying for) minors, and even against minors engaging in the act of smoking.{{Fact|date=July 2007}} Underlying such laws is the belief that people should make an informed decision regarding the risks of tobacco use. These laws have a lax enforcement in some nations and states. In other regions, cigarettes are still sold to minors because the fines for the violation are lower or comparable to the profit made from the sales to minors.{{Fact|date=July 2007}} However in China, Turkey, and many other countries usually a child will have little problem buying tobacco products, because they are often told to go to the store to buy tobacco for their parents. | Many countries have a ], In many countries, including the United States, most European Union member states, New Zealand, Canada, South Africa, Israel, India, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica and Australia, it is illegal to sell tobacco products to minors and in the Netherlands, Austria, Belgium, Denmark and South Africa it is illegal to sell tobacco products to people under the age of 16. On September 1, 2007 the minimum age to buy tobacco products in ] rose from 16 to 18, as well as in ] where on October 1, 2007 it rose from 16 to 18.<ref></ref> In 46 of the 50 United States, the minimum age is 18, except for Alabama, Alaska, New Jersey, and Utah where the legal age is 19 (also in Onondaga County in upstate New York, as well as Suffolk and Nassau Counties of Long Island, New York).{{Fact|date=July 2007}} Some countries have also legislated against giving tobacco products to (i.e. buying for) minors, and even against minors engaging in the act of smoking.{{Fact|date=July 2007}} Underlying such laws is the belief that people should make an informed decision regarding the risks of tobacco use. These laws have a lax enforcement in some nations and states. In other regions, cigarettes are still sold to minors because the fines for the violation are lower or comparable to the profit made from the sales to minors.{{Fact|date=July 2007}} However in China, Turkey, and many other countries usually a child will have little problem buying tobacco products, because they are often told to go to the store to buy tobacco for their parents. | ||

| Line 366: | Line 370: | ||

| In the ], a packet of cigarettes typically costs between £4.25 and £5.50 depending on the brand purchased and where the purchase was made<ref></ref>. The UK has a strong ] for cigarettes which has formed as a result of the high taxation, and it is estimated 27% of cigarette and 68% of handrolling tobacco consumption was non-UK duty paid (NUKDP) .<ref></ref>. | In the ], a packet of cigarettes typically costs between £4.25 and £5.50 depending on the brand purchased and where the purchase was made<ref></ref>. The UK has a strong ] for cigarettes which has formed as a result of the high taxation, and it is estimated 27% of cigarette and 68% of handrolling tobacco consumption was non-UK duty paid (NUKDP) .<ref></ref>. | ||

| === Advertising |

=== Advertising === | ||

| {{Main|Tobacco advertising}} | {{Main|Tobacco advertising}} | ||

Revision as of 00:46, 15 February 2009

Tobacco smoking is the inhalation of smoke from burned dried or cured leaves of the tobacco plant, most often in the form of a cigarette. People may smoke casually for pleasure, habitually to satisfy an addiction to the nicotine present in tobacco and to the act of smoking, or in response to social pressure. In some societies, people smoke for ritualistic purposes. According to the WHO about one-third of the world's male population smokes tobacco.

Tobacco use by Native Americans throughout North and South America dates back to 2000 BC. The practice was brought back to Europe by the crew of Christopher Columbus. Tobacco smoking took hold in Spain and then was introduced to the rest of the world by trade. Tobacco is an agricultural product processed from the fresh leaves of plants in the genus Nicotiana. Tobacco has been growing on the northern continents since about 6000 BC and began being used by native cultures at about 3000 BC. It has been smoked in one form or another since about 2000 BC. There are pictoral drawings of ancient Mayans smoking crude cigars from 1400 BC.

Tobacco smoke contains the psychoactive alkaloids nicotine and harmane, which combined give rise to addictive stimulant and euphoriant properties. The effect of nicotine in first time or irregular users is an increase in alertness and memory, and mild euphoria. Nicotine also disturbs metabolism and suppresses appetite. This is because nicotine, like many stimulants, temporarily increases blood sugar levels.

Medical research has determined that tobacco smoking causes lung cancer, emphysema, and cardiovascular disease among other health problems. The World Health Organization reported that tobacco smoking killed 100 million people worldwide in the 20th century and warned that it could kill one billion people around the world in the 21st century.

Consumption

For more about different products and methods of consumption, see Tobacco products.- Beedi

- Beedis are thin, often flavored, South Asian cigarette made of tobacco wrapped in a tendu leaf, and secured with colored thread at one end. Bidis smoke produce higher levels of carbon monoxide, nicotine, and tar than cigarettes typical in the United States. Due to the relatively low cost of beedies compared with regular cigarettes, they have long been popular among the poor in Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Cambodia and India.

- Cigars

- Cigars are tightly rolled bundle of dried and fermented tobacco which is ignited so that its smoke may be drawn into the smoker's mouth. They are generally not inhaled because the high alkalinity of the smoke, which can quickly become irritating to the trachea and lungs. Instead they are generally drawn into the mouth. The prevalence of cigar smoking varies depending on location, historical period, and population surveyed, and prevalence estimates vary somewhat depending on the survey method. The United Staets is the top consuming country by far, followed by Germany and the United Kingdom; the US and Western Europe account for about 75% of cigar sales worldwide. As of 2005 it is estimated that 4.3% of men and 0.3% of women smoke cigars.

- Cigarettes

- Cigarettes, French for "small cigar", are a product consumed through smoking and manufactured out of cured and finely cut tobacco leaves and reconstituted tobacco, often combined with other additives, which are then rolled or stuffed into a paper-wrapped cylinder. Cigarettes are ignited and inhaled, usually through a cellulose acetate filter, into the mouth and lungs. Cigarette smoking is the most common method of consumption.

- Electronic cigarette

- Electronic cigarettes is an alternative to tobacco smoking, although no tobacco is consumed. It is a battery-powered device that provides inhaled doses of nicotine by delivering a vaporized propylene glycol/nicotine solution. Many legislation and public health investigations are currently pending in many countries due to its relatively recent emergence.

- Hookah

- Hookah are a single or multi-stemmed (often glass-based) water pipe for smoking. Originally from India, the hookah has gained immense popularity, especially in the middle east. A hookah operates by water filtration and indirect heat. It can be used for smoking herbal fruits, tobacco, or cannabis.

- Kreteks

- Kreteks are cigarettes made with a complex blend of tobacco, cloves and a flavoring "sauce". It was first introduced in the 1880s in Kudus, Java, to deliver the medicinal eugenol of cloves to the lungs. The quality and variety of tobacco play an important role in kretek production, from which kreteks can contain more than 30 types of tobacco. Minced dried clove buds weighing about 1/3 of the tobacco blend are added to add flavouring. Several states in the United States have baned Kreteks, and in 2004 the United States prohibited cigarettes from having a "characterising flavor" of certain ingredients other than tobacco and menthol, thereby removing Kreteks from being classified as cigarettes.

- Roll-Your-Own

- Roll-Your-Own or hand-rolled cigarettes, are very popular particularly in European countries. These are prepared from loose tobacco, cigarette papers and filters all bought separately. They are usually much cheaper to make.

- Pipe smoking

- Pipe smoking typically consists of a small chamber (the bowl) for the combustion of the tobacco to be smoked and a thin stem (shank) that ends in a mouthpiece (the bit). Shredded pieces of tobacco are placed into the chamber and ignited. Tobaccos for smoking in pipes are often carefully treated and blended to achieve flavour nuances not available in other tobacco products.

Demographics

Main article: Prevalence of tobacco consumptionAs of 2000, smoking is practiced by 1.22 billion people. Assuming no change in prevalence it is predicted that 1.45 billion people will smoke in 2010 and 1.5 to 1.9 billion in 2025. Assuming that prevalence will decrease at 1% a year and that there will be a modest increase of income of 2%, it is predicted the number of smokers will stand at 1.3 billion in 2010 and 2025.

Smoking is generally five times higher among men than women, however the gender gap begins decline with younger age. As of 2002 in China 67% of men smoke as to 4% of women, however among teens the gap closes to 33% among men as to 8% with women. In developed countries smoking rates for men have peaked and have begun to decline, however for women they continue to climb.

As of 2002, about twenty percent of young teens (13–15) smoke worldwide. From which 80,000 to 100,000 children begin smoking every day—roughly half of which live in Asia. Evidence shows that around half of those who begin smoking in adolescent years go on to smoke for 15 to 20 years.

The WHO states that "Much of the disease burden and premature mortality attributable to tobacco use disproportionately affect the poor". Of the 1.22 billion smokers, 1 billion of them live in developing or transitional economies. While up to 30% of men are former smokers in developed countries, only 2% of men in China have quit, and 10% in Vietnam. Rates of smoking have leveled off or declined in the developed world, from which the United States have dropped by half from 1965 to 2006 falling from 42% to 20.8% in adults. In the developing world, however, tobacco consumption is rising by 3.4% per year as of 2002.

The WHO in 2004 projected 58.8 million deaths to occur globally, from which 5.4 million are tobacco-attributed, and 4.9 million as of 2007. As of 2002, 70% of the deaths are in developing countries.

Health effects

Main article: Health effects of tobaccoHistorical link

As the use of tobacco became popular in Europe, a number of people became concerned about its negative effects. One of the first was King James I of Great Britain. In his 1604 treatise, A Counterblaste to Tobacco, King James observed that smoking was:

A custome lothsome to the eye, hatefull to the Nose, harmfull to the braine, dangerous to the Lungs, and in the blacke stinking fume thereof, nearest resembling the horrible Stigian smoke of the pit that is bottomelesse.

The late-19th century invention of automated cigarette-making machinery in the American South made possible mass production of cigarettes at low cost, and cigarettes became elegant and fashionable among society men as the Victorian era gave way to the Edwardian. In 1912, American Dr. Isaac Adler was the first to strongly suggest that lung cancer is related to smoking. In 1929, Fritz Lickint of Dresden, Germany, published a formal statistical evidence of a lung cancer–tobacco link, based on a study showing that lung cancer sufferers were likely to be smokers. Lickint also argued that tobacco use was the best way to explain the fact that lung cancer struck men four or five times more often than women (since women smoked much less).

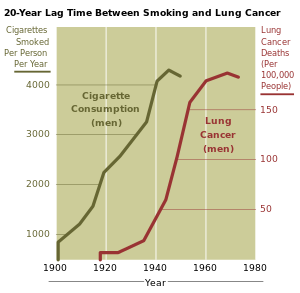

Prior to World War I, lung cancer was considered to be a rare disease, which most physicians would never see during their career. With the postwar rise in popularity of cigarette smoking, however, came a virtual epidemic of lung cancer.

In 1950, Richard Doll published research in the British Medical Journal showing a close link between smoking and lung cancer. Four years later, in 1954 the British Doctors Study, a study of some 40 thousand doctors over 20 years, confirmed the suggestion, based on which the government issued advice that smoking and lung cancer rates were related. The British Doctors Study lasted till 2001, with result published every ten years and final results published in 2004 by Doll and Richard Peto. Much early research was also done by Dr. Ochsner. Reader's Digest magazine for many years published frequent anti-smoking articles. In 1964 the United States Surgeon General's Report on Smoking and Health (referenced below), led millions of American smokers to quit, the banning of certain advertising, and the requirement of warning labels on tobacco products.

Effects

The main health risks in tobacco pertain to diseases of the cardiovascular system, in particular myocardial infarction (heart attack), cardiovascular disease, diseases of the respiratory tract such as Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), asthma, emphysema, and cancer, particularly lung cancer and cancers of the larynx and tongue.

A person's increased risk of contracting disease is directly proportional to the length of time that a person continues to smoke as well as the amount smoked. However, if someone stops smoking, then these chances gradually decrease as the damage to their body is repaired. A year after quitting, the risk of contracting heart disease is half that of a continuing smoker. The health risks of smoking are not uniform across all smokers. Risks vary according to amount of tobacco smoked, with those who smoke more at greater risk. Light smoking is still a health risk. Likewise, smoking "light" cigarettes does not reduce the risks.

The data regarding smoking to date focuses primarily on cigarette smoking, which increases mortality rates by 40% in those who smoke less than 10 cigarettes a day, by 70% in those who smoke 10–19 a day, by 90% in those who smoke 20–39 a day, and by 120% in those smoking two packs a day or more. Pipe smoking has also been researched and found to increase the risk of various cancers by 33%.

Some studies suggest that hookah smoking is considered to be safer than other forms of smoking. However, water is not effective for removing all relevant toxins, e.g. the carcinogenic aromatic hydrocarbons are not water-soluble. Several negative health effects are linked to hookah smoking and studies indicate that it is likely to be more harmful than cigarettes, due in part to the volume of smoke inhaled. In addition to the cancer risk, there is some risk of infectious disease resulting from pipe sharing, and other risks associated with the common addition of other psychoactive drugs to the tobacco.

Diseases caused by tobacco smoking are significant hazards to public health. According to the Canadian Lung Association, tobacco kills between 40,000–45,000 Canadians per year, more than the total number of deaths from AIDS, traffic accidents, suicide, murder, fires and accidental poisoning. The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention describes tobacco use as "the single most important preventable risk to human health in developed countries and an important cause of premature death worldwide."

A new research has found that women who smoke are at significantly increased risk of developing an abdominal aortic aneurysm, a condition in which a weak area of the abdominal aorta expands or bulges.

Carcinogenicity

Smoke, or any partially burnt organic matter, is carcinogenic (cancer-causing). The damage a continuing smoker does to their lungs can take up to 20 years before its physical manifestation in lung cancer. Women began smoking later than men, so the rise in death rate amongst women did not appear until later. The male lung cancer death rate decreased in 1975 — roughly 20 years after the fall in cigarette consumption in men. A fall in consumption in women also began in 1975 but by 1991 had not manifested in a decrease in lung cancer related mortalities amongst women.

Smoke contains several carcinogenic pyrolysis products that bind to DNA and cause genetic mutations. Particularly potent carcinogens are polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), which are toxicated to mutagenic epoxides. The first PAH to be identified as a carcinogen in tobacco smoke was benzopyrene, which has been shown to toxicate into an epoxide that irreversibly attaches to a cell's nuclear DNA, which may either kill the cell or cause a genetic mutation. If the mutation inhibits programmed cell death, the cell can survive to become a cancer cell. Similarly, acrolein, which is abundant in tobacco smoke, also irreversibly binds to DNA, causes mutations and thus also cancer. However, it needs no activation to become carcinogenic.

The carcinogenity of tobacco smoke is not explained by nicotine per se, which is not carcinogenic or mutagenic. However, it inhibits apoptosis, therefore accelerating existing cancers. Also, NNK, a nicotine derivative converted from nicotine, can be carcinogenic.

To reduce cancer risk but to deliver nicotine, there are tobacco products such as the electronic cigarette where the tobacco is not pyrolysed, but the nicotine is vaporized with solvent such as glycerol. However, such products have not become popular.

Cardiovascular

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) caused by smoking, known as tobacco disease, is a permanent, incurable reduction of pulmonary capacity characterized by shortness of breath, wheezing, persistent cough with sputum, and damage to the lungs, including emphysema and chronic bronchitis.

Psychological

Nicotine is a highly addictive psychoactive chemical. When tobacco is smoked, most of the nicotine is pyrolyzed; a dose sufficient to cause mild somatic dependency and mild to strong psychological dependency remains. There is also a formation of harmane (a MAO inhibitor) from the acetaldehyde in cigarette smoke, which seems to play an important role in nicotine addiction probably by facilitating dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens in response to nicotine stimuli. According to studies by Henningfield and Benowitz, overall nicotine is more addictive than cannabis, caffeine, ethanol, cocaine, and heroin when considering both somatic and psychological dependence. However, due to the stronger withdrawal effects of ethanol, cocaine and heroin, nicotine may have a lower potential for somatic dependence than these substances. A study by Perrine concludes that nicotine's potential for psychological dependency exceeds all other studied drugs - even ethanol, an extremely physically addictive substance with severe withdrawal symptoms that can be fatal. About half of Canadians who currently smoke have tried to quit. McGill University health professor Jennifer O'Loughlin stated that nicotine addiction can occur as soon as five months after the start of smoking.

Recent evidence has shown that smoking tobacco increases the release of dopamine in the brain, specifically in the mesolimbic pathway, the same neuro-reward circuit activated by drugs of abuse such as heroin and cocaine. This suggests nicotine use has a pleasurable effect that triggers positive reinforcement. One study found that smokers exhibit better reaction-time and memory performance compared to non-smokers, which is consistent with increased activation of dopamine receptors. Neurologically, rodent studies have found that nicotine self-administration causes lowering of reward thresholds--a finding opposite that of most other drugs of abuse (e.g. cocaine and heroin). This increase in reward circuit sensitivity persisted months after the self-administration ended, suggesting that nicotine's alteration of brain reward function is either long lasting or permanent. Furthermore, it has been found that nicotine can activate long term potentiation in vivo and in vitro. These studies suggests nicotine’s "trace memory" may contribute to difficulties in nicotine abstinence.

Recent studies have linked smoking to anxiety disorders, suggesting the correlation (and possibly mechanism) may be related to the broad class of anxiety disorders, and not limited to just depression. Current ongoing research are attempting to explore the addiction-anxiety relationship.

Data from multiple studies suggest that anxiety disorders such as depression play a role in cigarette smoking. A history of regular smoking was observed more frequently among individuals who had experienced a major depressive disorder at some time in their lives than among individuals who had never experienced major depression or among individuals with no psychiatric diagnosis. People with major depression are also much less likely to quit due to the increased risk of experiencing mild to severe states of depression, including a major depressive episode. Depressed smokers appear to experience more withdrawal symptoms on quitting, are less likely to be successful at quitting, and are more likely to relapse.

Pulmonary

Smoking contributes to the risk of developing heart disease. All smoke contains very fine particulates that are able to penetrate the alveolar wall into the blood and exert their effects on the heart in a short time.

Inhalation of tobacco smoke causes several immediate responses within the heart and blood vessels. Within one minute the heart rate begins to rise, increasing by as much as 30 percent during the first 10 minutes of smoking. Carbon monoxide in tobacco smoke exerts its negative effects by reducing the blood’s ability to carry oxygen.

Smoking tends to increase blood cholesterol levels. Furthermore, the ratio of high-density lipoprotein (the “good” cholesterol) to low-density lipoprotein (the “bad” cholesterol) tends to be lower in smokers compared to non-smokers. Smoking also raises the levels of fibrinogen and increases platelet production (both involved in blood clotting) which makes the blood viscous. Carbon monoxide binds to haemoglobin (the oxygen-carrying component in red blood cells), resulting in a much stabler complex than haemoglobin bound with oxygen or carbon dioxide -- the result is permanent loss of blood cell functionality. Blood cells are naturally recycled after a certain period of time, allowing for the creation of new, functional erythrocytes. However, if carbon monoxide exposure reaches a certain point before they can be recycled, hypoxia (and later death) occurs. All these factors make smokers more at risk of developing various forms of arteriosclerosis. As the arteriosclerosis progresses, blood flows less easily through rigid and narrowed blood vessels, making the blood more likely to form a thrombosis (clot). Sudden blockage of a blood vessel may lead to an infarction (e.g. stroke). However, it is also worth noting that the effects of smoking on the heart may be more subtle. These conditions may develop gradually given the smoking-healing cycle (the human body heals itself between periods of smoking), and therefore a smoker may develop less significant disorders such as worsening or maintenance of unpleasant dermatological conditions, e.g. eczema, due to reduced blood supply. Smoking also increases blood pressure and weakens blood vessels.

After a ban on smoking in all enclosed public places was introduced in Scotland in March 2006, there was a 17 percent reduction in hospital admissions for acute coronary syndrome. 67% of the decrease occurred in non-smokers.

Benefits

Studies suggest that smoking decreases appetite, but did not conclude that overweight people should smoke or that their health would improve by smoking.

Several types of "Smoker’s Paradoxes", (cases where smoking appears to have specific beneficial effects), have been observed; often the actual mechanism remains undetermined. Risk of ulcerative colitis has been frequently shown to be reduced by smokers on a dose-dependent basis; the effect is eliminated if the individual stops smoking. Smoking appears to interfere with development of Kaposi's sarcoma, breast cancer among women carrying the very high risk BRCA gene, preeclampsia, and atopic disorders such as allergic asthma. A plausible mechanism of action in these cases may be the nicotine in tobacco smoke acting as an anti-inflammatory agent and interfering with the disease process.

Evidence suggests that non-smokers are up to twice as likely as smokers to develop Parkinson's disease or Alzheimer's disease. A plausible explanation for these cases may be the effect of nicotine, a cholinergic stimulant, decreasing the levels of acetylcholine in the smoker's brain; Parkinson's disease occurs when the effect of dopamine is less than that of acetylcholine. In addition, nicotine stimulates the mesolimbic dopamine pathway (as do other drugs of abuse), causing an effective increase in dopamine levels. Opponents counter by noting that consumption of pure nicotine may be as beneficial as smoking without the risks associated with smoking.

It has been hypothesized that schizophrenics smoke for self-medication. Considering the high rates of physical sickness and deaths among persons suffering from schizophrenia, one of smoking's short term benefits is its temporary effect to improve alertness and cognitive functioning in that disease. It has been postulated that the mechanism of this effect is that schizophrenics have a disturbance of nicotinic receptor functioning. Rates of smoking have been found to be much higher in schizophrenics.

Passive smoking

Main article: Passive smoking

Passive or involuntary smoking occurs when the exhaled and ambient smoke (otherwise known as environmental or secondhand smoke) from one person's cigarette is inhaled by other people. Passive smoking involves inhaling carcinogens, as well as other toxic components, that are present in secondhand tobacco smoke.

Secondhand smoke is known to harm children, infants and reproductive health through acute lower respiratory tract illness, asthma induction and exacerbation, chronic respiratory symptoms, middle ear infection, lower birth weight babies, and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, or SIDS. In a study published on August 25, 2004 smoke-free policies were linked to a short-term reduction in admissions for acute myocardial infarction. In a study released on February 12, 2006 warning signs for cardiovascular disease are higher in people exposed to secondhand tobacco smoke, adding to the link between "passive smoke" and heart disease. "Our study provides further evidence to suggest low-level exposure to secondhand smoke has a clinically important effect on susceptibility to cardiovascular disease," said Dr. Andrea Venn of University of Nottingham in Britain, lead author of the study.

According to the U.S. Surgeon General’s Report (Chapter 5; pages 180–194), secondhand smoke is connected to SIDS. Infants who die from SIDS tend to have higher concentrations of nicotine and cotinine (a biological marker for secondhand smoke exposure) in their lungs than those who die from other causes. Infants exposed to secondhand smoke after birth are also at a greater risk of SIDS.

According to earlier studies the smoking ban led to significant improvements regarding respiratory symptoms and lung function in people visiting bars and restaurants. Previously scientists stated that environmental tobacco smoke leads to coronary heart disease, lung cancer and premature death.

The case is available in the February edition of the American Journal of Industrial Medicine.

Social and economic impact

Healthcare costs

In countries where there is a public health system, society covers the cost of medical care for smokers who become ill through in the form of increased taxes. Two arguments exist on this front, the "pro-smoking" argument suggesting that heavy smokers generally don't live long enough to develop the costly and chronic illnesses which affect the elderly, reducing society's healthcare burden. The "anti-smoking" argument suggests that the healthcare burden is increased because smokers get chronic illnesses younger and at a higher rate than the general population.

Data on both positions is limited. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published research in 2002 claiming that the cost of each pack of cigarettes sold in the United States was more than $7 in medical care and lost productivity. The cost may be higher, with another study putting it as high as $41 per pack, most of which however is on the individual and his/her family. This is how one author of that study puts it when he explains the very low cost for others: "The reason the number is low is that for private pensions, Social Security, and Medicare — the biggest factors in calculating costs to society — smoking actually saves money. Smokers die at a younger age and don't draw on the funds they've paid into those systems."

By contrast, some non-scientific studies, including one conducted by Philip Morris in the Czech Republic and another by the Cato Institute, support the opposite position. Neither study was peer-reviewed nor published in a scientific journal, and the Cato Institute has received funding from tobacco companies in the past. Philip Morris has explicitly apologised for the former study, saying: "The funding and public release of this study which, among other things, detailed purported cost savings to the Czech Republic due to premature deaths of smokers, exhibited terrible judgment as well as a complete and unacceptable disregard of basic human values. For one of our tobacco companies to commission this study was not just a terrible mistake, it was wrong. All of us at Philip Morris, no matter where we work, are extremely sorry for this. No one benefits from the very real, serious and significant diseases caused by smoking."

Between 1970 an 1995, per-capita cigarette consumption in poorer developing countries increased by 67 percent, while it dropped by 10 percent in the richer developed world. Eighty percent of smokers now live in less developed countries. By 2030, the World Health Organization (WHO) forecasts that 10 million people a year will die of smoking-related illness, making it the single biggest cause of death worldwide, with the largest increase to be among women. WHO forecasts' the 21st century's death rate from smoking to be ten times the 20th century's rate. ("Washingtonian" magazine, December 2007).

Tobacco and other drugs

Main article: Tobacco and other drugsA number of studies have been conducted to explore the relationship between tobacco and other drug use. While the association between smoking tobacco and other drug use has been well-established, the nature of this association remains unclear. The two main theories are the phenotypic causation (gateway) model and the correlated liabilities model. The causation model argues that smoking is a primary influence on future drug use, while the correlated liabilities model argues that smoking and other drug use are predicated on genetic or environmental factors.

Projecting an image

Famous smokers of the past used cigarettes or pipes as part of their image, such as Jean Paul Sartre's Gauloise-brand cigarettes, Albert Einstein's, Joseph Stalin's, Douglas MacArthur's, Bertrand Russell's, and Bing Crosby's pipes, or the news broadcaster Edward R. Murrow's cigarette. Writers in particular seemed to be known for smoking; see, for example, Cornell Professor Richard Klein's book Cigarettes are Sublime for the analysis, by this professor of French literature, of the role smoking plays in 19th and 20th century letters. The popular author Kurt Vonnegut addressed his addiction to cigarettes within his novels. British Prime Minister Harold Wilson was well known for smoking a pipe in public as was Winston Churchill for his cigars. Sherlock Holmes, the fictional detective created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle smoked a pipe, cigarettes, and cigars, besides injecting himself with cocaine, "to keep his overactive brain occupied during the dull London days, when nothing happened". The DC Vertigo comic book character, John Constantine, created by Alan Moore, is synonymous with smoking, so much so that the first storyline by Preacher creator, Garth Ennis, centred around John Constantine contracting lung cancer. Professional wrestler James Fullington, while in character as "The Sandman", is a chronic smoker in order to appear "tough".

Consumption influences

Advertising

Main article: Tobacco advertisingBefore the 1970s, most tobacco advertising was legal in the United States and most European nations. In the United States, in the 1950s and 1960s, cigarette brands were frequently sponsors of television shows—most notably shows such as To Tell the Truth and I've Got a Secret.

One of the most famous television jingles of the era came from an advertisement for Winston cigarettes. The slogan "Winston tastes good like a cigarette should!" proved to be catchy, and is still quoted today. When used to introduce Gunsmoke (gun = smoke), two gun shots were heard in the middle of the jingle just when listeners were expecting to hear the word "cigarette". Other popular slogans from the 1960s were "Us Tareyton smokers would rather fight than switch!," which was used to advertise Tareyton cigarettes, and "I'd Walk a Mile for a Camel".

In the 1950s, manufacturers began adding filter tips to cigarettes to remove some of the tar and nicotine as they were smoked. "Safer", "less potent" cigarette brands were also introduced. Light cigarettes became so popular that, as of 2004, half of American smokers preferred them over regular cigarettes , in spite the fact that the idea of a "safer" cigarette is a myth. Cigarettes that offer "low tar and nicotine" cause the smoker to smoke more or to inhale more deeply to get the same level of nicotine. According to The Federal Government’s National Cancer Institute (NCI), light cigarettes provide no benefit to smoker's health.

In the United States, it was believed by many that tobacco companies were marketing tobacco smoking to minors. For example, Reynolds American Inc. used the Joe Camel cartoon figure, with the slogan "Smooth character", to advertise Camel cigarettes. In 1997 "Camel Wides" were introduced, with claims that a wider cigarette would be more "smooth".

Meanwhile other brands such as Virginia Slims were targeting women with slogans like "You've come a long way, Baby" and "Slimmer than the fat cigarettes men smoke". There was an inference that boys or men who smoked a narrow ("slim") cigarette, actually less fast-burning and less profitable to the industry, could be teased for being effeminate.

In 1964, the Surgeon General of the United States, released the Surgeon General's Advisory Committee Report on Smoking and Health. It was based on over 7000 scientific articles that linked tobacco use with cancer and other diseases. This report led to laws requiring warning labels on tobacco products and to restrictions on tobacco advertisements. As these began to come into force, tobacco marketing became more subtle, with sweets shaped like cigarettes put on the market, and a number of advertisements designed to appeal to children, particularly those featuring Joe Camel resulting in increased awareness and uptake of smoking among children. However, restrictions did have an effect on adult quit rates, with its use declining to the point that by 2004, nearly half of all Americans who had ever smoked had quit.

Many nations, including Russia and Greece, still allow billboards advertising tobacco use. Tobacco smoking is still advertised in special magazines, during sporting events, in gas stations and stores, and in more rare cases on television. Some nations, including the UK and Australia, have begun anti-smoking advertisements to counter the effects of tobacco advertising.

The actual effectiveness of tobacco advertisement is widely documented. According to an opinion piece by Henry Saffer, public health experts say that tobacco advertising increases cigarette consumption and there is much empirical literature that finds a significant effect of tobacco advertising on smoking, especially in children. A Dutch tobacco company manufactures "Pink Elephant" vanilla-flavored cigarettes, and "Black Devil" chocolate-flavored cigarettes.

Peer-pressure

Many anti-smoking organizations claim that teenagers begin their smoking habits due to peer pressure, and cultural influence portrayed by friends. However, one study found that direct pressure to smoke cigarettes did not play a significant part in adolescent smoking. In that study, adolescents also reported low levels of both normative and direct pressure to smoke cigarettes. A similar study showed that individuals play a more active role in starting to smoke than has previously been acknowledged and that social processes other than peer pressure need to be taken into account. Another study's results revealed that peer pressure was significantly associated with smoking behavior across all age and gender cohorts, but that intrapersonal factors were significantly more important to the smoking behavior of 12–13 year-old girls than same-age boys. Within the 14–15 year-old age group, one peer pressure variable emerged as a significantly more important predictor of girls' than boys' smoking. It is debated whether peer pressure or self-selection is a greater cause of adolescent smoking. It is arguable that the reverse of peer-pressure is true, when the majority of peers do not smoke and ostracize those who do.

Parental

Children of smoking parents are more likely to smoke than children with non-smoking parents. One study found that parental smoking cessation was associated with less adolescent smoking, except when the other parent currently smoked. A current study tested the relation of adolescent smoking to rules regulating where adults are allowed to smoke in the home. Results showed that restrictive home smoking policies were associated with lower likelihood of trying smoking for both middle and high school students.

Depictions in popular culture

Exposure to smoking in movies has been linked with adolescent smoking initiation in cross-sectional studies. Films tend to have a high incidence of smoking behavior vis-a-vis the general population. According to a study of movies created between 1988 and 1997, eighty-seven percent of these movies portrayed various tobacco use, with an average of 5 occurrences per film. R-rated movies had the greatest number of occurrences and were most likely to feature major characters using tobacco. Despite the declining tobacco use in the society, the incidence of smoking in 2002 movies was nearly the same as in 1950 movies.

Universal Pictures has a "Policy Regarding Tobacco Depictions in Films". In films anticipated to be released in the United States with a G, PG or PG-13 rating, smoking incidents (depiction of tobacco smoking, tobacco-related signage or paraphernalia) appear only when there is a substantial reason for doing so. In that case the film is released with a health warning in end credits, DVD packaging, etc.

Since May 2007 the Motion Picture Association of America may give a film glamorizing smoking or depicting pervasive smoking outside of a historic or other mitigating context a higher rating.

There have also been moves to reduce the depiction of protagonists smoking in television shows, especially those aimed at children. For example, Ted Turner took steps to remove or edit scenes that depict characters smoking in cartoons such as Tom and Jerry, The Flintstones and Scooby-Doo, which are shown on his Cartoon Network and Boomerang television channels.

There are also indications in the TIGRS video game content rating system.

Continued smoking

The reasons given by smokers for this activity are broadly categorized as "addictive smoking", "pleasure from smoking", "tension reduction/relaxation", "social smoking", "stimulation", "habit/automatism", and "handling". There are gender differences in how much each of these reasons contribute, with females more likely than males to cite "tension reduction/relaxation", "stimulation" and "social smoking".

Some smokers argue that the depressant effect of smoking allows them to calm their nerves, often allowing for increased concentration. However, according to the Imperial College London, "Nicotine seems to provide both a stimulant and a depressant effect, and it is likely that the effect it has at any time is determined by the mood of the user, the environment and the circumstances of use. Studies have suggested that low doses have a depressant effect, whilst higher doses have stimulant effect." However, it is impossible to differentiate a drug effect brought on by nicotine use, and the alleviation of nicotine withdrawal.

The lack of deterrence by the deleterious health effects is a prototypical example of optimism bias. Also, other reason for this are lack of understanding of probability, the fact that the effects usually kick in at a older age, and personality traits or disorders that generally produce high-risk or self-destructive behavior.

Consumption patterns

A number of studies have established that cigarette sales and smoking follow distinct time-related patterns. For example, cigarette sales in the United States of America have been shown to follow a strongly seasonal pattern, with the high months being the months of summer, and the low months being the winter months.

Similarly, cigarette smoking activity has been shown to follow distinct circadian patterns during the waking day, with the high point usually occurring shortly after waking in the morning or going to sleep at night.

Religious views

Main article: Religious views on smokingIn most major religions, tobacco smoking is not specifically prohibited, although it may be discouraged as an immoral habit.

Communal smoking of a sacred tobacco pipe is a common ritual of many Native American tribes, and was considered a sacred part of their religion. Sema, the Anishinaabe word for tobacco, was grown for ceremonial use and considered the ultimate sacred plant since its smoke was believed to carry prayers to the heavens. The tobacco used during these rituals varies widely in potency — the Nicotiana rustica species used in South America, for instance, has up to twice the nicotine content of the common North American N. tabacum.

Before the health risks of smoking were identified through controlled study, smoking was considered an immoral habit by certain Christian preachers and social reformers. The founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, Joseph Smith, Jr, recorded that on February 27, 1833, he received a revelation which addressed tobacco use. Eventually accepted as a commandment, adherent Mormons do not smoke.

Jehovah's Witnesses base their stand against smoking on the Bible's command to "clean ourselves of every defilement of flesh" (2 Corinthians 7:1)

The Jewish Rabbi Yisrael Meir Kagan (1838–1933) was one of the first Jewish authorities to speak out on smoking.

In the Sikh religion, tobacco smoking is strictly forbidden.

In the Bahá'í Faith, smoking tobacco is discouraged though not forbidden.

Smoking cessation

Main article: Smoking cessationMany of tobacco's health effects can be minimized through smoking cessation. The British doctors study showed that those who stopped smoking before they reached 30 years of age lived almost as long as those who never smoked. It is also possible to reduce the risks by reducing the frequency of smoking and by proper diet and exercise. Some research has indicated that some of the damage caused by smoking tobacco can be moderated with the use of antioxidants.

Smokers wanting to quit or to temporarily abstain from smoking can use a variety of nicotine-containing tobacco substitutes, or nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) products to temporarily lessen the physical withdrawal symptoms, the most popular being nicotine gum and lozenges. Nicotine patches are also used for smoking cessation. Medications that do not contain nicotine can also be used, such as bupropion (Zyban or Wellbutrin) and varenicline (Chantix).

Peer support can be helpful, such as that provided by support groups and telephone quitlines.

Restrictions

On February 27, 2005 the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, took effect. The FCTC is the world's first public health treaty. Countries that sign on as parties agree to a set of common goals, minimum standards for tobacco control policy, and to cooperate in dealing with cross-border challenges such as cigarette smuggling. Currently the WHO declares that 4 billion people will be covered by the treaty, which includes 168 signatories. Among other steps, signatories are to put together legislation that will eliminate secondhand smoke in indoor workplaces, public transport, indoor public places and, as appropriate, other public places.

Age

Many countries have a smoking age, In many countries, including the United States, most European Union member states, New Zealand, Canada, South Africa, Israel, India, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica and Australia, it is illegal to sell tobacco products to minors and in the Netherlands, Austria, Belgium, Denmark and South Africa it is illegal to sell tobacco products to people under the age of 16. On September 1, 2007 the minimum age to buy tobacco products in Germany rose from 16 to 18, as well as in Great Britain where on October 1, 2007 it rose from 16 to 18. In 46 of the 50 United States, the minimum age is 18, except for Alabama, Alaska, New Jersey, and Utah where the legal age is 19 (also in Onondaga County in upstate New York, as well as Suffolk and Nassau Counties of Long Island, New York). Some countries have also legislated against giving tobacco products to (i.e. buying for) minors, and even against minors engaging in the act of smoking. Underlying such laws is the belief that people should make an informed decision regarding the risks of tobacco use. These laws have a lax enforcement in some nations and states. In other regions, cigarettes are still sold to minors because the fines for the violation are lower or comparable to the profit made from the sales to minors. However in China, Turkey, and many other countries usually a child will have little problem buying tobacco products, because they are often told to go to the store to buy tobacco for their parents.

Taxation

See Cigarette taxes in the United States for a state-by-state comparison.

Many governments have introduced excise taxes on cigarettes in order to reduce the consumption of cigarettes. Money collected from the cigarette taxes are frequently used to pay for tobacco use prevention programs, therefore making it a method of internalizing external costs.

In 2002, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said that each pack of cigarettes sold in the United States costs the nation more than $7 in medical care and lost productivity. That's over $2000 per year/smoker. Another study by a team of health economists finds the combined price paid by their families and society is about $41 per pack of cigarettes.

Substantial scientific evidence shows that higher cigarette prices result in lower overall cigarette consumption. Most studies indicate that a 10% increase in price will reduce overall cigarette consumption by 3% to 5%. Youth, minorities, and low-income smokers are two to three times more likely to quit or smoke less than other smokers in response to price increases. Smoking is often cited as an example of an inelastic good, however, i.e. a large rise in price will only result in a small decrease in consumption.

Many nations have implemented some form of tobacco taxation. As of 1997, Denmark had the highest cigarette tax burden of $4.02 per pack. Taiwan only had a tax burden of $0.62 per pack. Currently, the average price and excise tax on cigarettes in the United States is well below those in many other industrialized nations.

Cigarette taxes vary widely from state to state in the United States. For example, South Carolina has a cigarette tax of only 7 cents per pack, the nation's lowest, while New Jersey has the highest cigarette tax in the U.S.: $2.575 per pack. In Alabama, Illinois, Missouri, New York City, Tennessee, and Virginia, counties and cities may impose an additional limited tax on the price of cigarettes. Due to the high tax rate, the price of an average pack of cigarettes in New Jersey is $6.45, which is still less than the approximated external cost of a pack of cigarettes.

In Canada, cigarette taxes have raised prices of the more expensive brands to upwards of ten CAD$.

In the United Kingdom, a packet of cigarettes typically costs between £4.25 and £5.50 depending on the brand purchased and where the purchase was made. The UK has a strong black market for cigarettes which has formed as a result of the high taxation, and it is estimated 27% of cigarette and 68% of handrolling tobacco consumption was non-UK duty paid (NUKDP) ..

Advertising

Main article: Tobacco advertising

Several Western countries have also put restrictions on cigarette advertising. In the United States, all television advertising of tobacco products has been prohibited since 1971. In Australia, the Tobacco Advertising Prohibition Act 1992 prohibits tobacco advertising in any form, with a very small number of exceptions (some international sporting events were accepted, but these exceptions were revoked in 2006).

All tobacco advertising and sponsorship on television has been banned within the European Union since 1991 under the Television Without Frontiers Directive (1989) This ban was extended in 2005 by the Tobacco Advertising Directive to cover other forms of media such as the internet, print media, and radio. This directive does not affect purely local media such as billboards, as regulating these falls outside the jusisdiction of the European Commission. However, most member states have transposed the directive with national laws that are wider in scope than the directive and cover local advertising.

Other countries have legislated particularly against advertising that appears to target minors.

Warnings

Main article: Tobacco packaging warning messagesSome countries also impose legal requirements on the packaging of tobacco products. For example in the countries of the European Union, Turkey, Australia and South Africa, cigarette packs must be prominently labeled with the health risks associated with smoking. Canada, Australia, Thailand, Iceland and Brazil have also imposed labels upon cigarette packs warning smokers of the effects, and they include graphic images of the potential health effects of smoking. Cards are also inserted into cigarette packs in Canada. There are sixteen of them, and only one comes in a pack. They explain different methods of quitting smoking. Also, in the United Kingdom, there have been a number of graphic NHS advertisements, one showing a cigarette filled with fatty deposits, as if the cigarette is symbolising the artery of a smoker.

Currently in Australia, almost 70% of the cigarette packet (including 1/3 of the front, the whole back and both sides) are covered in graphic images of the effects of smoking as well as information about the names and numbers of chemicals and annual death rates. Television ads accompany them, including video footage of smokers struggling to breathe in hospital. Since then, the number of smokers has been reduced by one quarter. Singapore similarly requires cigarette manufacturers to print images of mouths, feet and blood vessels adversely affected by smoking.

France has the additional requirement of listing on the side of all packaging the percentages of tobacco present, compared to the weight of the paper and additives present. For one U.S. manufacturer of cigarettes sold in France, the side list indicates only 85.0% is tobacco, 9.0% are the additives, and paper constitutes another 6.0% of the total weight of a cigarette. Filters are not part of the formula. The additives are a syrup sprayed on the chopped tobacco leaf on the conveyor belt and is a combination of the 599 additive ingredients as submitted to Member of Congress Henry Waxman in a 50 page list by the five major U.S. tobacco companies during his Congressional Hearings on April 14, 1994.

Bans

Main article: Smoking banSeveral countries such as the Ireland, Latvia, Estonia, The Netherlands, France, Finland, Norway, Canada, Australia, Sweden, Portugal, Singapore, Italy, Indonesia, India, Lithuania, Chile, Spain, Iceland, United Kingdom, Slovenia and Malta have legislated against smoking in public places, often including bars and restaurants. Restaurateurs have been permitted in some jurisdictions to build designated smoking areas (or to prohibit smoking). In the United States, many states prohibit smoking in restaurants, and some also prohibit smoking in bars. In provinces of Canada, smoking is illegal in indoor workplaces and public places, including bars and restaurants. As of March 31, 2008 Canada has introduced a smoking ban in all public places, as well as within 10 meters of an entrance to any public place. In Australia, smoking bans vary from state to state. Currently, Queensland has total bans within all public interiors (including workplaces, bars, pubs and eateries) as well as patrolled beaches and some outdoor public areas. There are, however, exceptions for designated smoking areas. In Victoria, smoking is banned in train stations, bus stops and tram stops as these are public locations where second hand smoke can affect non-smokers waiting for public transport, and since July 1, 2007 is now extended to all indoor public places. In New Zealand and Brazil, smoking is banned in enclosed public places mainly bars, restaurants and pubs. Hong Kong banned smoking on January 1, 2007 in the workplace, public spaces such as restaurants, karaoke rooms, buildings, and public parks. Bars serving alcohol who do not admit under-18s have been exempted till 2009. In Romania smoking is illegal in trains, metro stations, public institutions (except where designated, usually outside) and public transportation.

See the List of smoking bans article for a full list of restrictions in various areas around the world.

Gallery

-

A Nama woman smoking in the Kalahari Desert

-

A man smoking outside of Northwest Cancer Specialists

A man smoking outside of Northwest Cancer Specialists

-

A cigarette with filter.

A cigarette with filter.

-

Various smoking equipment.

Various smoking equipment.

See also

- Cannabis smoking

- Cigarette

- Cigarette taxes in the United States

- Tobacco and health

- History of commercial tobacco in the United States

- Smoking pipe

- Smoking ban

References

Notes

- Smoking Statistics WHO Fact Sheet May 28, 2002

- List of health effects by CDC

- List of health effects by Australia's myDr

- Tobacco Could Kill One Billion By 2100, WHO Report Warns Science Daily February 8, 2008

- Tobacco could kill more than 1 billion this century: WHO Australian Broadcasting Corporation February 8, 2008

- "Bidi Use Among Urban Youth -- Massachusetts, March-April 1999". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1999-09-17. Retrieved 2009-02-14.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=,|dateformat=, and|coauthors=(help) - Pakhale SS, Maru GB. (1998-12-12). "Distribution of major and minor alkaloids in tobacco, mainstream and sidestream smoke of popular Indian smoking products". Parel, Mumbai, India: Tata Memorial Centre. PMID 9862656.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|day=,|month=,|laysummary=, and|laysource=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Rarick CA (2008-04-02). "Note on the premium cigar industry". SSRN. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Mariolis P, Rock VJ, Asman K; et al. (2006). "Tobacco use among adults—United States, 2005". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 55 (42): 1145–8.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wingand, Jeffrey S. (2006). "ADDITIVES, CIGARETTE DESIGN and TOBACCO PRODUCT REGULATION" (PDF). Mt. Pleasant, MI 48804: Jeffrey Wigand. Retrieved 2009-02-14.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|dateformat=and|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location (link) - "A bill to protect the public health by providing the Food and Drug Administration with certain authority to regulate tobacco products. (Summary)" (Press release). Library of Congress. 20 May 2004. Retrieved 2007-08-01.

{{cite press release}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - WHO REPORT on the global TOBACCO epidemic 2008, pp.267–288.

- ^ "Guindon & Boisclair" 2004, pp. 13-16.

- Women and the Tobacco Epidemic: Challenges for the 21st Century 2001, pp.5-6.

- Surgeon General's Report—Women and Smoking 2001, p.47.

- ^ "WHO/WPRO-Smoking Statistics". World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific. 2002-05-28. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - Mortality from Smoking in Developed Countries 1950-2000: indirect estimates from national vital statistics 2006, p.9.

- "WHO/WPRO-Tobacco". World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific. 2005. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - VJ Rock, MPH, A Malarcher, PhD, JW Kahende, PhD, K Asman, MSPH, C Husten, MD, R Caraballo, PhD (2007-11-09). "Cigarette Smoking Among Adults --- United States, 2006". United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

In 2006, an estimated 20.8% (45.3 million) of U.S. adults

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - The Global Burden of Disease 2004 Update 2008, p.8.

- The Global Burden of Disease 2004 Update 2008, p.23.

- ^ "WHO/WPRO-Tobacco Fact sheet". World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific. 2007-05-29. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - Isaac Adler. "Primary Malignant Growth of the Lung and Bronchi". (1912) New York, Longmans, Green. pp. 3-12. Reprinted (1980) by A Cancer Journal for Clinicians

- ^ Commentary: Schairer and Schoniger's forgotten tobacco epidemiology and the Nazi quest for racial purity - Proctor 30 (1): 31 - International Journal of Epidemiology

- Witschi (2001). "A Short History of Lung Cancer". Toxicol Sci. 64 (1): 4–6. PMID 11606795.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Adler I. Primary malignant growths of the lungs and bronchi. New York: Longmans, Green; 1912., cited in Spiro SG, Silvestri GA (September 1, 2005). "One hundred years of lung cancer". Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 172 (5): 523–529. doi:10.1164/rccm.200504-531OE. PMID 15961694.

- Doll, Rich (September 30, 1950). "Smoking and carcinoma of the lung. Preliminary report". British Medical Journal. 2 (4682): 739–48. PMID 14772469.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Doll Richard, Bradford Hilly A (June 26, 1954). "The mortality of doctors in relation to their smoking habits. A preliminary report". British Medical Journal. 328 (4877): 1451–55. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7455.1529. PMID 13160495.

- Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I (2004). "Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observation on male British doctors". PMID 15213107.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gilliland FD, Islam T, Berhane K, Gauderman WJ, McConnell R, Avol E, Peters JM. (November 15, 2006). "Regular smoking and asthma incidence in adolescents". Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 174 (10): 1094–1100. doi:10.1164/rccm.200605-722OC. PMID 16973983.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Smoking Cessation Guidelines" American Heart Foundation

- 1967 Surgeon General's Report on Smoking

- Henley; et al. (2004). "Association Between Exclusive Pipe Smoking and Mortality From Cancer and Other Diseases". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 96 (11): 853. doi:10.1093/jnci/djh144. PMID 15173269.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Yadav JS, Thakur S (2000). "Genetic risk assessment in hookah smokers". Cytobios. 101 (397): 101–13. PMID 10756983.

- Sajid KM, Akhter M, Malik GQ (1993). "Carbon monoxide fractions in cigarette and hookah (hubble bubble) smoke". J Pak Med Assoc. 43 (9): 179–82. PMID 8283598.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Knishkowy, B. (2005). "Water-Pipe (Narghile) Smoking: An Emerging Health Risk Behavior". Pediatrics. 116: e113. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-2173. PMID 15995011.

- Smoking and Teens, Canadian Lung Association, Newspaper articles, Canada, Canadian Cancer Society

- Allan Rock announces collaborative research initiative on smoking

- http://www.themedguru.com/articles/smoking_may_perk_up_womens_risk_of_developing_deadly_aaa-86114529.html

- Jones Mary, Fosbery Richard, Taylor Dennis (2000). "Answers to self-assessment questions". Biology 1. Cambridge Advanced Sciences. p. 250. ISBN 0-521-78719-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Feng, Z (2006). "Acrolein is a major cigarette-related lung cancer agent: Preferential binding at p53 mutational hotspots and inhibition of DNA repair". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (42): 15404–15409. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607031103. PMID 17030796.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Maneckjee, R (1994). "Opioids induce while nicotine suppresses apoptosis in human lung cancer cells". Cell Growth and Differentiation: the Molecular Biology Journal of the American Association of Cancer Research. 5 (10): 1033–1040. PMID 7848904.

- Devereux G (2006). "ABC of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Definition, epidemiology, and risk factors". BMJ. 332: 1142–1144. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7550.1142. PMID 16690673.

- Talhout R, Opperhuizen A, van Amsterdam JG (2007). "Role of acetaldehyde in tobacco smoke addiction". Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 17 (10): 627–36. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.02.013. PMID 17382522.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Relative Addictiveness of Drugs

- The Henningfield-Benowitz substance comparison charts

- ProCon.org - Addiction Chart

- AADAC |Truth About Tobacco - Addiction

- Cigarette addiction faster than expected. The London Free Press (August 2, 2006).

- Nicotine and the Brain

- The effects of cigarette smoking on overnight performance

- Depression and the dynamics of smoking. A national perspective

- Smoking, smoking cessation, and major depression

- Covey LS, Glassman AH, Stetner F (1998). "Cigarette smoking and major depression". J Addict Dis. 17 (1): 35–46. doi:10.1300/J069v17n01_04. PMID 9549601.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hall SM, Muñoz RF, Reus VI, Sees KL (1993). "Nicotine, negative affect, and depression". J Consult Clin Psychol. 61 (5): 761–7. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.61.5.761. PMID 7902368.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Haldane J (1895). "The action of carbonic oxide on man". J Physiol. 18: 430–462.

- Narkiewicz K, Kjeldsen SE, Hedner T (2005). "Is smoking a causative factor of hypertension?". Blood Press. 14 (2): 69–71. doi:10.1080/08037050510034202. PMID 16036482.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Pell JP, Haw S, Cobbe S; et al. (2008). "Smoke-free Legislation and Hospitalizations for Acute Coronary Syndrome". New England Journal of Medicine. 359: 482. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa0706740. PMID 18669427.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - News-Medical.Net, , accessed on Jan 3, 2008

- mytelus.com, , accessed on Jan 3, 2008

-

Cohen, David J (2001). "Impact of Smoking on Clinical and Angiographic Restenosis After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention". Circulation. 104: 773. doi:10.1161/hc3201.094225. PMID 11502701.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Longmore, M., Wilkinson, I., Torok, E. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine (Fifth Edition) p. 232

-

Green JT, Richardson C, Marshall RW, Rhodes J, McKirdy HC, Thomas GA, Williams GT (2000-11). "Nitric oxide mediates a therapeutic effect of nicotine in ulcerative colitis". Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 14 (11): 1429–1434. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00847.x. PMID 11069313.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) -

"Smoking Cuts Risk of Rare Cancer". UPI. March 29, 2001.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Recer Paul (May 19, 1998). "Cigarettes May Have an Up Side". AP. Retrieved November 6, 2006.

-

Lain Kristine Y, Powers Robert W, Krohn Marijane A, Ness Roberta B, Crombleholme William R, Roberts James M (1991). "Urinary cotinine concentration confirms the reduced risk of preeclampsia with tobacco exposure". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 181 (5): 908–914. PMID 11422156.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) -

Hjern A, Hedberg A, Haglund B, Rosen M (2001). "Does tobacco smoke prevent atopic disorders? A study of two generations of Swedish residents". Clin Exp Allergy. 31 (6): 908–914. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01096.x. PMID 11422156.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Melton Lisa (2006). "Body Blazes". Scientific American: 24.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) -

Fratiglioni L, Wang HX (2000). "Smoking and Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease: review of the epidemiological studies". Behav Brain Res. 113 (1–2): 117–120. doi:10.1016/S0166-4328(00)00206-0. PMID 10942038.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) -

Kumari, Veena (2006). "Nicotine use in schizophrenia: The self medication hypotheses". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 29 (6): 1021–1034. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.02.006.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Seeman MV (2007). "An outcome measure in schizophrenia: mortality". Can J Psychiatry. 52 (1): 55–60. PMID 17444079.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Auquier P, Lancon C, Rouillon F, Lader M, Holmes C (2006). "Mortality in schizophrenia". Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 15 (12): 873–879. doi:10.1002/pds.1325. PMID 17058327.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Compton, Michael T (2005). "Cigarette Smoking in Individuals with Schizophrenia". Medscape Psychiatry & Mental Health. 10 (2).

- Ripoll N, Bronnec M, Bourin M (2004). "Nicotinic Receptors and Schizophrenia". Curr Med Res Opin. 20 (7): 1057–1074. doi:10.1185/030079904125004060.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kelly Ciara, McCreadie Robin (2000). "Cigarette smoking and schizophrenia". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 6 (5): 327–331. doi:10.1192/apt.6.5.327.

- Short-term effects of Italian smoking regulation on rates of hospital admission for acute myocardial infarction

- Effective Tobacco Control Measures

- "Secondhand Smoke Raises Heart Disease Risk". Reuters, February 12, 2007.

- "Remarks at press conference to launch Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General". Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- Woman's Death Linked to Second-Hand Smoking

- ^ Cigarettes Cost U.S. $7 Per Pack Sold, Study Says

- ^ Study: Cigarettes cost families, society $41 per pack

- ^ "Public Finance Balance of Smoking in the Czech Republic".

- "Snuff the Facts".

- Light but just as deadly, by Peter Lavelle. The Pulse, October 21, 2004.

- The Truth About "Light" Cigarettes: Questions and Answers, from the National Cancer Institute factsheet

- 'Safer' cigarette myth goes up in smoke, by Andy Coghlan. New Scientist, 2004

- Behind the Smokescreen: Tobacco Marketing to Kids

- While D, Kelly S, Huang W, Charlton A (1996). "Cigarette advertising and onset of smoking in children: questionnaire survey". BMJ. 313 (7054): 398–9. PMC 2351819. PMID 8761227.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cigarette Smoking Among Adults — United States, 2004 MMWR Weekly, November 11, 2005.

- Botvin GJ, Goldberg CJ, Botvin EM, Dusenbury L (1993). "Smoking behavior of adolescents exposed to cigarette advertising". Public Health Rep. 108 (2): 217–24. PMC 1403364. PMID 8464979.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Evans N, Farkas A, Gilpin E, Berry C, Pierce JP (1995). "Influence of tobacco marketing and exposure to smokers on adolescent susceptibility to smoking". J Natl Cancer Inst. 87 (20): 1538–45. doi:10.1093/jnci/87.20.1538. PMID 7563188.