| Revision as of 04:26, 6 December 2005 editClockworkSoul (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers18,824 editsm disambiguation link repair (You can help!)← Previous edit | Revision as of 05:59, 9 December 2005 edit undo128.253.179.145 (talk) →United States of AmericaNext edit → | ||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

| After ], public opinion towards eugenics and sterilization programs became more negative in the light of the connection with the ] policies of ], though a significant number of sterilizations continued in a few states until the early 1960s. The ] Board of Eugenics, later renamed the Board of Social Protection, existed until 1983, with the last forcible sterilization occurring in 1981. The U.S. ] ] had a sterilization program as well. Some states continued to have sterilization laws on the books for much longer after that, though they were rarely if ever used. California sterilized more than any other state by a wide margin, and was responsible for over a third of all sterilization operations. Information about the California sterilization program was produced into book form and widely disseminated by eugenicists ] and ], which was said by the government of ] to be of key importance in proving that large-scale compulsory sterilization programs were feasible. | After ], public opinion towards eugenics and sterilization programs became more negative in the light of the connection with the ] policies of ], though a significant number of sterilizations continued in a few states until the early 1960s. The ] Board of Eugenics, later renamed the Board of Social Protection, existed until 1983, with the last forcible sterilization occurring in 1981. The U.S. ] ] had a sterilization program as well. Some states continued to have sterilization laws on the books for much longer after that, though they were rarely if ever used. California sterilized more than any other state by a wide margin, and was responsible for over a third of all sterilization operations. Information about the California sterilization program was produced into book form and widely disseminated by eugenicists ] and ], which was said by the government of ] to be of key importance in proving that large-scale compulsory sterilization programs were feasible. | ||

| In recent years, the governors of many states have made public apologies for their past programs. None have offered to compensate those sterilized, however, citing that few are likely still living (and by definition would have no affected offspring) and that inadequate records remain by which to verify them. At least one compensation case, '']'' (]), was filed in the courts; on the grounds that the sterilization law was unconstitutional |

In recent years, the governors of many states have made public apologies for their past programs. None have offered to compensate those sterilized, however, citing that few are likely still living (and by definition would have no affected offspring) and that inadequate records remain by which to verify them. At least one compensation case, '']'' (]), was filed in the courts; on the grounds that the sterilization law was unconstitutional. It was rejected because the law was no longer in effect at the time of the filing. However the petitioners were granted some compensation as the stipulations of the law itself, which required informing the patients about their operations, had not been carried out in many cases. | ||

| ==Germany== | ==Germany== | ||

Revision as of 05:59, 9 December 2005

Compulsory sterilization programs sprouted up in many countries at the beginning of the 20th century, usually as part of a program of "negative" eugenics -- to prevent "undesirable" members of the population reproducing. They generally specified that an institution or legal body could order that an individual be operated upon, for the purpose of preventing further procreation, against their will (and sometimes without their knowledge).

Usually such programs advocated sterilization by means of vasectomy in males and salpingectomy or tubal ligation in females, as they were not operations which significantly affected sexual drive or the personality of the individuals operated upon (unlike, for example, castration). This increased the seemingly innocuous nature of the operations, adding a veneer of scientific objectivity.

Plans for forced sterilization for the purposes of avoiding overpopulation are sometimes, but not usually, directly related to a eugenic intent. (See population control for more information on this type of sterilization.)

United States of America

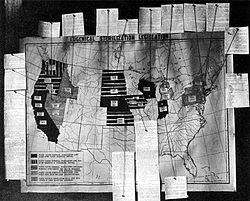

The first country to concertedly undertake compulsory sterilization programs for the purpose of eugenics was the United States of America. The principal targets of the American program were the mentally retarded and the mentally ill, but also targeted under many state laws were the deaf, the blind, the epileptic, the physically deformed, and even orphans, the homeless, and homosexuals. Some sterilizations also took place in prisons and other penal institutions, targeting criminality, but they were in the relative minority. In the end, over 65,000 individuals were sterilized in 33 states under state compulsory sterilization programs in the United States.

The first state to introduce compulsory sterilization legislation was Pennsylvania, in 1905, but after being passed by the state legislature was vetoed by the governor. Indiana became the first state to enact sterilization legislation in 1907 followed closely by Washington and California in 1909. Sterilization rates across the country were relatively low (California being the sole exception) until the 1927 Supreme Court case Buck v. Bell which legitimized the forced sterilization of patients at a Virginia home for the mentally retarded. The number of sterilizations performed per year increased until another Supreme Court case, Skinner v. Oklahoma, complicated the legal situation by ruling against punitive sterilization in 1942.

Most sterilization laws could be divided into three main categories of motivations: eugenic (concerned with heredity), therapeutic (part of an even-then obscure medical theory that sterilization would lead to vitality), or punitive (as a punishment for criminals), though of course these motivations could be combined in practice and theory (sterilization of criminals could be both punitive and eugenic, for example). Buck v. Bell asserted only that eugenic sterilization was constitutional, whereas Skinner v. Oklahoma ruled specifically against punitive sterilization, for example. Most operations only worked to prevent reproduction (such as severing the vas deferens in males), though some states (Oregon and North Dakota in particular) had laws which called for the use of castration. In general, most sterilizations were performed under eugenic statutes, in state-run psychiatric hospitals and homes for the mentally disabled. There was never a federal sterilization statute, though eugenicist Harry H. Laughlin, whose state-level "Model Eugenical Sterilization Law" was the basis of the statute affirmed in Buck v. Bell, proposed the structure of one in 1922.

After World War II, public opinion towards eugenics and sterilization programs became more negative in the light of the connection with the genocidal policies of Nazi Germany, though a significant number of sterilizations continued in a few states until the early 1960s. The Oregon Board of Eugenics, later renamed the Board of Social Protection, existed until 1983, with the last forcible sterilization occurring in 1981. The U.S. insular area Puerto Rico had a sterilization program as well. Some states continued to have sterilization laws on the books for much longer after that, though they were rarely if ever used. California sterilized more than any other state by a wide margin, and was responsible for over a third of all sterilization operations. Information about the California sterilization program was produced into book form and widely disseminated by eugenicists E.S. Gosney and Paul B. Popenoe, which was said by the government of Adolf Hitler to be of key importance in proving that large-scale compulsory sterilization programs were feasible.

In recent years, the governors of many states have made public apologies for their past programs. None have offered to compensate those sterilized, however, citing that few are likely still living (and by definition would have no affected offspring) and that inadequate records remain by which to verify them. At least one compensation case, Poe v. Lynchburg Training School & Hospital (1981), was filed in the courts; on the grounds that the sterilization law was unconstitutional. It was rejected because the law was no longer in effect at the time of the filing. However the petitioners were granted some compensation as the stipulations of the law itself, which required informing the patients about their operations, had not been carried out in many cases.

Germany

The most infamous sterilization program of the 20th century took place under the most infamous regime of the 20th century: the Third Reich. One of the first acts by Adolf Hitler after achieving total control over the German state was to pass the Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring (Gesetz zur Verhütung erbkranken Nachwuchses) in July 1933. The law was signed in by Hitler himself, and over 200 eugenic courts were created specifically as a result of the law. Under the German law, any doctor in the Reich was required to report patients of theirs who were mentally retarded, mentally ill (including schizophrenia and manic depression), epileptic, blind, deaf, or physically deformed, and a steep monetary penalty was imposed for any patients who were not properly reported. Individuals suffering from alcoholism or Huntington's Chorea could also be sterilized. The individual's case was then presented in front of a court of Nazi officials and public health officers who would review their medical records, take testimony from friends and colleagues, and eventually decide whether or not to order a sterilization operation performed on the individual, using force if necessary. Though not explicitly covered by the law, 400 mixed-race "Rhineland Bastards" were also sterilized beginning in 1937.

By the end of World War II, over 400,000 individuals were sterilized under the German law and its revisions, most within its first four years of being enacted. When the issue of compulsory sterilization was brought up at the Nuremberg trials after the war, many Nazis defended their actions on the matter by indicating that it was the United States itself from whom they had taken inspiration.

Other countries

Even years and decades after the large-scale forced sterilization programs had ceased to exist in the US, many countries maintained post-WWII sterilization campaigns lasting well into the 70s, most notoriously Sweden and Canada. Dozens of countries around the world, especially in Europe, also had similar programs, and in 1997 it was disclosed that Sweden in particular had a strong sterilization program, sterilizing around 62,000 individuals over a period of 40 years until 1976. Other countries that had notably active sterilization programs include Canada, Australia, Norway, Finland, Estonia, Slovakia, Switzerland, Iceland, and some countries in Latin America (including Panama). In the United Kingdom, Home Secretary Winston Churchill introduced a bill that included forced sterilization. Writer G.K. Chesterton led a successful effort to defeat that clause of the 1913 Mental Deficiency Act. The Catholic Church has been a notable opponent of eugenics and sterilization programs.

India and China have also at various times implemented sterilization campaigns as a population control policy, though only the latter has made any previous overtures towards any potential eugenic random motivations.

External links

- "Three Generations, No Imbeciles: Virginia, Eugenics, and Buck v. Bell" (USA)

- Eugenics Archive (USA)

- "Deadly Medicine: Creating the Master Race" (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum exhibit) (Germany, USA)

- "Sterilization Law in Germany" (includes text of 1933 German law in appendix)