| Revision as of 21:08, 11 August 2009 edit81.106.135.150 (talk) →Space-time intervals: - Check this.← Previous edit | Revision as of 22:34, 24 August 2009 edit undoSchlafly (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users2,368 edits →Privileged character of 3+1 spacetime: remove false and unsupported paragraphNext edit → | ||

| Line 144: | Line 144: | ||

| == Privileged character of 3+1 spacetime == | == Privileged character of 3+1 spacetime == | ||

| Reasoning about spacetime is always limited by the scientific evidence and technology available at the time of writing. For example, in the latter 20th century, experiments with ]s revealed that protons gained mass when accelerated to high speeds, and the time required for particle decay and other physical phenomena rose. Special relativity predicts this. Authors writing before Einstein's discovery of special relativity were unaware of these facts, so that their views were often mistaken, even fanciful.{{Fact|date=October 2008}} | |||

| There are two kinds of dimensions, spatial (bidirectional) and temporal (unidirectional). Let the number of spatial dimensions be ''N'' and the number of temporal dimensions be ''T''. That ''N''=3 and ''T''=1, setting aside the compactified dimensions invoked by ] and undetectable to date, can be explained by appealing to the physical consequences of letting ''N'' differ from 3 and ''T'' differ from 1. The argument is often of an ] character. | There are two kinds of dimensions, spatial (bidirectional) and temporal (unidirectional). Let the number of spatial dimensions be ''N'' and the number of temporal dimensions be ''T''. That ''N''=3 and ''T''=1, setting aside the compactified dimensions invoked by ] and undetectable to date, can be explained by appealing to the physical consequences of letting ''N'' differ from 3 and ''T'' differ from 1. The argument is often of an ] character. | ||

| Line 161: | Line 159: | ||

| For an elementary treatment of the privileged status of ''N''=3 and ''T''=1, see chpt. 10 (esp. Fig. 10.12) of Barrow;<ref>{{cite book| last = Barrow| first = J. D.| authorlink = John D. Barrow | title = The Constants of Nature| publisher = Pantheon Books| date= 2002| location = | pages =| url =| doi =| id = }}.</ref> for deeper treatments, see §4.8 of Barrow and Tipler (1986) and Tegmark.<ref>{{cite journal| last = Tegmark| first = Max| authorlink = Max Tegmark| title = On the dimensionality of spacetime| journal = Classical and Quantum Gravity| volume = 14 | issue = 4| pages = L69–L75| publisher =| date= April 1997| url = http://www.iop.org/EJ/abstract/0264-9381/14/4/002| doi = 10.1088/0264-9381/14/4/002| id =| accessdate = 2006-12-16 }}</ref> Barrow has repeatedly cited the work of ].<ref>] (1955) " ," ''British Journal of the Philosophy of Science'' 6: 13. Also see his (1959) ''The Structure and Evolution of the Universe''. London: Hutchinson.</ref> | For an elementary treatment of the privileged status of ''N''=3 and ''T''=1, see chpt. 10 (esp. Fig. 10.12) of Barrow;<ref>{{cite book| last = Barrow| first = J. D.| authorlink = John D. Barrow | title = The Constants of Nature| publisher = Pantheon Books| date= 2002| location = | pages =| url =| doi =| id = }}.</ref> for deeper treatments, see §4.8 of Barrow and Tipler (1986) and Tegmark.<ref>{{cite journal| last = Tegmark| first = Max| authorlink = Max Tegmark| title = On the dimensionality of spacetime| journal = Classical and Quantum Gravity| volume = 14 | issue = 4| pages = L69–L75| publisher =| date= April 1997| url = http://www.iop.org/EJ/abstract/0264-9381/14/4/002| doi = 10.1088/0264-9381/14/4/002| id =| accessdate = 2006-12-16 }}</ref> Barrow has repeatedly cited the work of ].<ref>] (1955) " ," ''British Journal of the Philosophy of Science'' 6: 13. Also see his (1959) ''The Structure and Evolution of the Universe''. London: Hutchinson.</ref> | ||

| ] builds on the notion that the "universe is wiggly" and hypothesizes that matter and energy are composed of tiny vibrating strings of various types, most of which are embedded in dimensions that exist only on a scale no larger than the ]. Hence ''N''=3 and ''T''=1 do not characterize string theory, which embeds vibrating strings in coordinate grids having 10, even 26, dimensions. | ] builds on the notion that the "universe is wiggly" and hypothesizes that matter and energy are composed of tiny vibrating strings of various types, most of which are embedded in dimensions that exist only on a scale no larger than the ]. Hence ''N''=3 and ''T''=1 do not characterize string theory, which embeds vibrating strings in coordinate grids having 10, even 26, dimensions. There is no evidence for string theory. | ||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

Revision as of 22:34, 24 August 2009

For other uses of this term, see Spacetime (disambiguation).

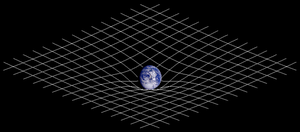

In physics, spacetime (or space–time) is any mathematical model that combines space and time into a single continuum. Spacetime is usually interpreted with space being three-dimensional and time playing the role of a fourth dimension that is of a different sort than the spatial dimensions. According to certain Euclidean space perceptions, the universe has three dimensions of space and one dimension of time. By combining space and time into a single manifold, physicists have significantly simplified a large number of physical theories, as well as described in a more uniform way the workings of the universe at both the supergalactic and subatomic levels.

In classical mechanics, the use of Euclidean space instead of spacetime is appropriate, as time is treated as universal and constant, being independent of the state of motion of an observer. In relativistic contexts, however, time cannot be separated from the three dimensions of space, because the rate at which time passes depends on an object's velocity relative to the speed of light and also on the strength of intense gravitational fields, which can slow the passage of time.

Concept with dimensions

The concept of spacetime combines space and time within a single coordinate system, typically with three spatial dimensions: length, width, height, and one temporal dimension: time. Dimensions are components of a coordinate grid typically used to locate a point in a certain defined "space" as, for example, on the globe by latitude and longitude. In spacetime, a coordinate grid that spans the 3+1 dimensions locates "events" (rather than just points in space), so time is added as another dimension to the grid, and another axis. This way, you have where and when something is. Unlike in normal spatial coordinates, there are restrictions for how measurements can be made spatially and temporally. These restrictions correspond roughly to a particular mathematical model which differs from Euclidean space in its manifest symmetry.

Formerly, from experiments at low speeds, time was believed to be independent of motion, progressing at a fixed rate in all reference frames; however, later high-speed experiments revealed that time slowed down at higher speeds (with such slowing called "time dilation" explained in the theory of "special relativity" ). Many experiments have confirmed time dilation, such as atomic clocks onboard a Space Shuttle running slower than synchronized Earth-bound inertial clocks and the relativistic decay of muons from cosmic ray showers. The duration of time can therefore vary for various events and various reference frames. When dimensions are understood as mere components of the grid system, rather than physical attributes of space, it is easier to understand the alternate dimensional views as being simply the result of coordinate transformations.

The term spacetime has taken on a generalized meaning beyond treating spacetime events with the normal 3+1 dimensions (including time). It is really the combination of space and time. Other proposed spacetime theories include additional dimensions—normally spatial but there exist some speculative theories that include additional temporal dimensions and even some that include dimensions that are neither temporal nor spatial. How many dimensions are needed to describe the universe is still an open question. Speculative theories such as string theory predict 10 or 26 dimensions (with M-theory predicting 11 dimensions: 10 spatial and 1 temporal), but the existence of more than four dimensions would only appear to make a difference at the subatomic level.

Historical origin

The first reference to spacetime was in 1754 by Jean le Rond d'Alembert in the article Dimension in Encyclopedie. Another early venture was by Joseph Louis Lagrange in his Theory of Analytic Functions(1797, 1813). He said, "One may view mechanics as a geometry of four dimensions, and mechanical analysis as an extension of geometric analysis".

After discovering quaternions, William Rowan Hamilton commented, "Time is said to have only one dimension, and space to have three dimensions. ... The mathematical quaternion partakes of both these elements; in technical language it may be said to be 'time plus space', or 'space plus time': and in this sense it has, or at least involves a reference to, four dimensions. And how the One of Time, of Space the Three, Might in the Chain of Symbols girdled be." Lorentz discovered some invariances of Maxwell's equations late in the 19th century which were to become the basis of Einstein's theory of special relativity. Fiction authors were also in on the game: Edgar Allan Poe stated in his essay on cosmology titled Eureka (1848) that "Space and duration are one." In 1895, in his novel The Time Machine, H.G. Wells wrote, "There is no difference between time and any of the three dimensions of space except that our consciousness moves along it." He added, "Viking people…know very well that time is only a kind of space." It has always been the case that time and space are measured using real numbers, and the suggestion that the dimensions of space and time could be switched could have been raised by the first people to have formalized physics, but ultimately, the contradictions between Maxwell's laws and Galilean relativity had to come to a head before the idea of spacetime was ready to become mainstream.

While spacetime can be viewed as a consequence of Albert Einstein's 1905 theory of special relativity, it was first explicitly proposed mathematically by one of his teachers, the mathematician Hermann Minkowski, in a 1908 essay building on and extending Einstein's work. His concept of Minkowski space is the earliest treatment of space and time as two aspects of a unified whole, the essence of special relativity. The idea of Minkowski space also led to special relativity being viewed in a more geometrical way, this geometric viewpoint of spacetime being important in general relativity too. (For an English translation of Minkowski's article, see Lorentz et al. 1952.) The 1926 thirteenth edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica included an article by Einstein titled "Space–Time".

Basic concepts

Spacetimes are the arenas in which all physical events take place—an event is a point in spacetime specified by its time and place. For example, the motion of planets around the sun may be described in a particular type of spacetime, or the motion of light around a rotating star may be described in another type of spacetime. The basic elements of spacetime are events. In any given spacetime, an event is a unique position at a unique time. Examples of events include the explosion of a star or the single beat of a drum.

A spacetime is independent of any observer. However, in describing physical phenomena (which occur at certain moments of time in a given region of space), each observer chooses a convenient coordinate system. Events are specified by four real numbers in any coordinate system. The worldline of a particle or light beam is the path that this particle or beam takes in the spacetime and represents the history of the particle or beam. The worldline of the orbit of the Earth is depicted in two spatial dimensions x and y (the plane of the Earth's orbit) and a time dimension orthogonal to x and y. The orbit of the Earth is an ellipse in space alone, but its worldline is a helix in spacetime.

The unification of space and time is exemplified by the common practice of expressing distance in units of time, by dividing the distance measurement by the speed of light.

Space-time intervals

Spacetime entails a new concept of distance. Whereas distances in Euclidean spaces are entirely spatial and always positive, in special relativity, the concept of distance is quantified in terms of the space-time interval between two events, which occur in two locations at two times:

where:

- is the speed of light,

- and denote differences of the time and space coordinates, respectively, between the events.

(Note that the choice of signs for above follows the timelike convention (-+++). Other treatments reverse the sign of .)

Space-time intervals may be classified into three distinct types based on whether the temporal separation () or the spatial separation () of the two events is greater.

Certain types of worldlines (called geodesics of the spacetime) are the shortest paths between any two events, with distance being defined in terms of spacetime intervals. The concept of geodesics becomes critical in general relativity, since geodesic motion may be thought of as "pure motion" (inertial motion) in spacetime, that is, free from any external influences.

Time-like interval

For two events separated by a time-like interval, enough time passes between them for there to be a cause-effect relationship between the two events. For a particle traveling at less than the speed of light, any two events which occur to or by the particle must be separated by a time-like interval. Event pairs with time-like separation define a positive squared spacetime interval () and may be said to occur in each other's future or past. There exists a reference frame such that the two events are observed to occur in the same spatial location, but there is no reference frame in which the two events can occur at the same time.

The measure of a time-like spacetime interval is described by the proper time:

The proper time interval would be measured by an observer with a clock traveling between the two events in an inertial reference frame, when the observer's path intersects each event as that event occurs. (The proper time defines a real number, since the interior of the square root is positive.)

Light-like interval

In a light-like interval, the spatial distance between two events is exactly balanced by the time between the two events. The events define a squared spacetime interval of zero ().

Events which occur to or by a photon along its path (i.e., while travelling at , the speed of light) all have light-like separation. Given one event, all those events which follow at light-like intervals define the propagation of a light cone, and all the events which preceded from a light-like interval define a second light cone.

Space-like interval

When a space-like interval separates two events, not enough time passes between their occurrences for there to exist a causal relationship crossing the spatial distance between the two events at the speed of light or slower. Generally, the events are considered not to occur in each other's future or past. There exists a reference frame such that the two events are observed to occur at the same time, but there is no reference frame in which the two events can occur in the same spatial location.

For these space-like event pairs with a negative squared spacetime interval (), the measurement of space-like separation is the proper distance:

Like the proper time of time-like intervals, the proper distance () of space-like spacetime intervals is a real number value.

Mathematics of spacetimes

For physical reasons, a spacetime continuum is mathematically defined as a four-dimensional, smooth, connected Lorentzian manifold . This means the smooth Lorentz metric has signature . The metric determines the geometry of spacetime, as well as determining the geodesics of particles and light beams. About each point (event) on this manifold, coordinate charts are used to represent observers in reference frames. Usually, Cartesian coordinates are used. Moreover, for simplicity's sake, the speed of light is usually assumed to be unity.

A reference frame (observer) can be identified with one of these coordinate charts; any such observer can describe any event . Another reference frame may be identified by a second coordinate chart about . Two observers (one in each reference frame) may describe the same event but obtain different descriptions.

Usually, many overlapping coordinate charts are needed to cover a manifold. Given two coordinate charts, one containing (representing an observer) and another containing (representing another observer), the intersection of the charts represents the region of spacetime in which both observers can measure physical quantities and hence compare results. The relation between the two sets of measurements is given by a non-singular coordinate transformation on this intersection. The idea of coordinate charts as local observers who can perform measurements in their vicinity also makes good physical sense, as this is how one actually collects physical data—locally.

For example, two observers, one of whom is on Earth, but the other one who is on a fast rocket to Jupiter, may observe a comet crashing into Jupiter (this is the event ). In general, they will disagree about the exact location and timing of this impact, i.e., they will have different 4-tuples (as they are using different coordinate systems). Although their kinematic descriptions will differ, dynamical (physical) laws, such as momentum conservation and the first law of thermodynamics, will still hold. In fact, relativity theory requires more than this in the sense that it stipulates these (and all other physical) laws must take the same form in all coordinate systems. This introduces tensors into relativity, by which all physical quantities are represented.

Geodesics are said to be time-like, null, or space-like if the tangent vector to one point of the geodesic is of this nature. The paths of particles and light beams in spacetime are represented by time-like and null (light-like) geodesics (respectively).

Topology

Main article: Spacetime topologyThe assumptions contained in the definition of a spacetime are usually justified by the following considerations.

The connectedness assumption serves two main purposes. First, different observers making measurements (represented by coordinate charts) should be able to compare their observations on the non-empty intersection of the charts. If the connectedness assumption were dropped, this would not be possible. Second, for a manifold, the properties of connectedness and path-connectedness are equivalent and, one requires the existence of paths (in particular, geodesics) in the spacetime to represent the motion of particles and radiation.

Every spacetime is paracompact. This property, allied with the smoothness of the spacetime, gives rise to a smooth linear connection, an important structure in general relativity. Some important theorems on constructing spacetimes from compact and non-compact manifolds include the following:

- A compact manifold can be turned into a spacetime if, and only if, its Euler characteristic is 0.

- Any non-compact 4-manifold can be turned into a spacetime.

Spacetime symmetries

Main article: Spacetime symmetriesOften in relativity, spacetimes that have some form of symmetry are studied. As well as helping to classify spacetimes, these symmetries usually serve as a simplifying assumption in specialized work. Some of the most popular ones include:

Causal structure

Main article: Causal structureThe causal structure of a spacetime describes causal relationships between pairs of points in the spacetime based on the existence of certain types of curves joining the points.

Spacetime in special relativity

Main article: Minkowski spaceThe geometry of spacetime in special relativity is described by the Minkowski metric on R. This spacetime is called Minkowski space. The Minkowski metric is usually denoted by and can be written as a four-by-four matrix:

where the Landau–Lifshitz spacelike convention is being used. A basic assumption of relativity is that coordinate transformations must leave spacetime intervals invariant. Intervals are invariant under Lorentz transformations. This invariance property leads to the use of four-vectors (and other tensors) in describing physics.

Strictly speaking, one can also consider events in Newtonian physics as a single spacetime. This is Galilean-Newtonian relativity, and the coordinate systems are related by Galilean transformations. However, since these preserve spatial and temporal distances independently, such a spacetime can be decomposed into spatial coordinates plus temporal coordinates, which is not possible in the general case.

Spacetime in general relativity

In general relativity, it is assumed that spacetime is curved by the presence of matter (energy), this curvature being represented by the Riemann tensor. In special relativity, the Riemann tensor is identically zero, and so this concept of "non-curvedness" is sometimes expressed by the statement Minkowski spacetime is flat.

Many spacetime continua have physical interpretations which most physicists would consider bizarre or unsettling. For example, a compact spacetime has closed, time-like curves, which violate our usual ideas of causality (that is, future events could affect past ones). For this reason, mathematical physicists usually consider only restricted subsets of all the possible spacetimes. One way to do this is to study "realistic" solutions of the equations of general relativity. Another way is to add some additional "physically reasonable" but still fairly general geometric restrictions and try to prove interesting things about the resulting spacetimes. The latter approach has led to some important results, most notably the Penrose–Hawking singularity theorems.

Quantized spacetime

In general relativity, spacetime is assumed to be smooth and continuous—and not just in the mathematical sense. In the theory of quantum mechanics, there is an inherent discreteness present in physics. In attempting to reconcile these two theories, it is sometimes postulated that spacetime should be quantized at the very smallest scales. Current theory is focused on the nature of spacetime at the Planck scale. Causal sets, loop quantum gravity, string theory, and black hole thermodynamics all predict a quantized spacetime with agreement on the order of magnitude. Loop quantum gravity makes precise predictions about the geometry of spacetime at the Planck scale.

Privileged character of 3+1 spacetime

There are two kinds of dimensions, spatial (bidirectional) and temporal (unidirectional). Let the number of spatial dimensions be N and the number of temporal dimensions be T. That N=3 and T=1, setting aside the compactified dimensions invoked by string theory and undetectable to date, can be explained by appealing to the physical consequences of letting N differ from 3 and T differ from 1. The argument is often of an anthropic character.

Immanuel Kant argued that 3-dimensional space was a consequence of the inverse square law of universal gravitation. While Kant's argument is historically important, John D. Barrow says that it "...gets the punch-line back to front: it is the three-dimensionality of space that explains why we see inverse-square force laws in Nature, not vice-versa." (Barrow 2002: 204). This is because the law of gravitation (or any other inverse-square law) follows from the concept of flux, from N=3, and from 3-dimensional solid objects having surface areas proportional to the square of their size in a selected spatial dimension. In particular, a sphere of radius r has area of 4πr. More generally, in a space of N dimensions, the strength of the gravitational attraction between two bodies separated by a distance of r would be inversely proportional to r.

In 1920, Paul Ehrenfest showed that if we fix T= 1 and let N>3, the orbit of a planet about its sun cannot remain stable. The same is true of a star's orbit around the center of its galaxy. Ehrenfest also showed that if N is even, then the different parts of a wave impulse will travel at different speeds. If N>3 and odd, then wave impulses become distorted. Only when N=3 or 1 are both problems avoided. In 1922, Hermann Weyl showed that Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism works only when N=3 and T=1, writing that this fact "...not only leads to a deeper understanding of Maxwell's theory, but also of the fact that the world is four dimensional, which has hitherto always been accepted as merely 'accidental,'become intelligible through it." Finally, Tangherlini showed in 1963 that when N>3, electron orbitals around nuclei cannot be stable; electrons would either fall into the nucleus or disperse.

Max Tegmark expands on the preceding argument in the following anthropic manner. If T differs from 1, the behavior of physical systems could not be predicted reliably from knowledge of the relevant partial differential equations. In such a universe, intelligent life capable of manipulating technology could not emerge. Moreover, if T>1, Tegmark maintains that protons and electrons would be unstable and could decay into particles having greater mass than themselves. (This is not a problem if the particles have a sufficiently low temperature.) If N>3, Ehrenfest's argument above holds; atoms as we know them (and probably more complex structures as well) could not exist. If N<3, gravitation of any kind becomes problematic, and the universe is probably too simple to contain observers. For example, when N<3, nerves cannot overlap without intersecting.

In general, it is not clear how physical law could function if T differed from 1. If T>1, subatomic particles which decay after a fixed period would not behave predictably, because time-like geodesics would not be necessarily maximal. N=1 and T=3 has the peculiar property that the speed of light in a vacuum is a lower bound on the velocity of matter; all matter consists of tachyons.

Hence anthropic and other arguments rule out all cases except N=3 and T=1—which happens to describe the world about us. Curiously, the cases N=3 or 4 have the richest and most difficult geometry and topology. There are, for example, geometric statements whose truth or falsity is known for all N except one or both of 3 and 4. N=3 was the last case of the Poincare conjecture to be proved.

For an elementary treatment of the privileged status of N=3 and T=1, see chpt. 10 (esp. Fig. 10.12) of Barrow; for deeper treatments, see §4.8 of Barrow and Tipler (1986) and Tegmark. Barrow has repeatedly cited the work of Whitrow.

String theory builds on the notion that the "universe is wiggly" and hypothesizes that matter and energy are composed of tiny vibrating strings of various types, most of which are embedded in dimensions that exist only on a scale no larger than the Planck length. Hence N=3 and T=1 do not characterize string theory, which embeds vibrating strings in coordinate grids having 10, even 26, dimensions. There is no evidence for string theory.

See also

- Four-vector

- Fourth dimension

- Global spacetime structure

- List of mathematical topics in relativity

- Local spacetime structure

- Lorentz invariance

- Manifold

- Mathematics of general relativity

- Metric space

- Relativity of simultaneity

- Basic introduction to the mathematics of curved spacetime

- Frame-dragging

Notes

- R.C. Archibald (1914) Time as a fourth dimension Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 20:409.

- Hermann Minkowski, "Raum und Zeit", 80. Versammlung Deutscher Naturforscher (Köln, 1908). Published in Physikalische Zeitschrift 10 104–111 (1909) and Jahresbericht der Deutschen Mathematiker-Vereinigung 18 75-88 (1909). For an English translation, see Lorentz et al. (1952).

- Einstein, Albert, 1926, "Space-Time," Encyclopedia Britannica, 13th ed.

- Matolcsi, Tamás (1994). Spacetime Without Reference Frames. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

- Ehrenfest, Paul (1920), "How do the fundamental laws of physics make manifest that Space has 3 dimensions?", Annalen der Physik, 61: 440, doi:10.1002/andp.19203660503. Also see Ehrenfest, P. (1917) "In what way does it become manifest in the fundamental laws of physics that space has three dimensions?" Proceedings of the Amsterdam Academy 20: 200.

- Weyl, H. (1922) Space, time, and matter. Dover reprint: 284.

- Tangherlini, F. R. (1963). "Atoms in Higher Dimensions". Nuovo Cimento. 14 (27): 636.

- Tegmark, Max (April 1997). "On the dimensionality of spacetime". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 14 (4): L69–L75. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/14/4/002. Retrieved 2006-12-16.

- Dorling, J. (1970) "The Dimensionality of Time," American Journal of Physics 38(4): 539-40.

- Barrow, J. D. (2002). The Constants of Nature. Pantheon Books..

- Tegmark, Max (April 1997). "On the dimensionality of spacetime". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 14 (4): L69–L75. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/14/4/002. Retrieved 2006-12-16.

- Whitrow, G. J. (1955) " ," British Journal of the Philosophy of Science 6: 13. Also see his (1959) The Structure and Evolution of the Universe. London: Hutchinson.

References

- John D. Barrow and Frank J. Tipler (1986) The Anthropic Cosmological Principle. Oxford Univ. Press.

- Ehrenfest, Paul (1920) "How do the fundamental laws of physics make manifest that Space has 3 dimensions?" Annalen der Physik 61: 440.

- George F. Ellis and Ruth M. Williams (1992) Flat and curved space-times. Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 0-19-851164-7

- Isenberg, J. A. (1981) "Wheeler-Einstein-Mach spacetimes," Phys. Rev. D 24(2): 251–256.

- Kant, Immanuel (1929) "Thoughts on the true estimation of living forces" in J. Handyside, trans., Kant's Inaugural Dissertation and Early Writings on Space. Univ. of Chicago Press.

- Lorentz, H. A., Einstein, Albert, Minkowski, Hermann, and Weyl, Hermann (1952) The Principle of Relativity: A Collection of Original Memoirs. Dover.

- Lucas, John Randolph (1973) A Treatise on Time and Space. London: Methuen.

- Penrose, Roger (2004). The Road to Reality. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Chpts. 17–18.

- Poe, Edgar A. (1848). Eureka; An Essay on the Material and Spiritual Universe. Hesperus Press Limited. ISBN 1-84391-009-8.

- Robb, A. A. (1936). Geometry of Time and Space. University Press.

- Erwin Schrödinger (1950) Space-time structure. Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Schutz, J. W. (1997). Independent axioms for Minkowski Space-time. Addison-Wesley Longman.

- Tangherlini, F. R. (1963). "Atoms in Higher Dimensions". Nuovo Cimento. 14 (27): 636.

- Taylor, E. F. (1963). Spacetime Physics. W. H. Freeman.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Wells, H.G. (2004). The Time Machine. New York: Pocket Books. (pp. 5–6)

External links

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: "Space and Time: Inertial Frames" by Robert DiSalle.

| Time | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key concepts | |||||||||

| Measurement and standards |

| ||||||||

| Philosophy of time | |||||||||

| Human experience and use of time | |||||||||

| Time in science |

| ||||||||

| Related | |||||||||

| Time measurement and standards | ||

|---|---|---|

| International standards |

|   |

| Obsolete standards | ||

| Time in physics | ||

| Horology | ||

| Calendar | ||

| Archaeology and geology | ||

| Astronomical chronology | ||

| Other units of time | ||

| Related topics | ||

(spacetime interval),

(spacetime interval), is the speed of light,

is the speed of light, and

and  denote differences of the time and space coordinates, respectively, between the events.

denote differences of the time and space coordinates, respectively, between the events. above follows the

above follows the  ) or the spatial separation (

) or the spatial separation ( ) of the two events is greater.

) of the two events is greater.

) and may be said to occur in each other's future or past. There exists a

) and may be said to occur in each other's future or past. There exists a  (proper time).

(proper time).

).

).

), the measurement of space-like separation is the

), the measurement of space-like separation is the  (proper distance).

(proper distance). ) of space-like spacetime intervals is a real number value.

) of space-like spacetime intervals is a real number value.

. This means the smooth

. This means the smooth  has signature

has signature  . The metric determines the geometry of spacetime, as well as determining the

. The metric determines the geometry of spacetime, as well as determining the  are used. Moreover, for simplicity's sake, the speed of light

are used. Moreover, for simplicity's sake, the speed of light  . Another reference frame may be identified by a second coordinate chart about

. Another reference frame may be identified by a second coordinate chart about  (representing another observer), the intersection of the charts represents the region of spacetime in which both observers can measure physical quantities and hence compare results. The relation between the two sets of measurements is given by a

(representing another observer), the intersection of the charts represents the region of spacetime in which both observers can measure physical quantities and hence compare results. The relation between the two sets of measurements is given by a  and can be written as a four-by-four matrix:

and can be written as a four-by-four matrix: