| Revision as of 05:07, 13 November 2009 editJ04n (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators162,685 editsm Repairing links to disambiguation pages - You can help!← Previous edit | Revision as of 08:26, 13 November 2009 edit undoRCS (talk | contribs)7,222 edits →Modern acknowledgments: See talk page. Stop pushing for that quote by a slick politician who has no qualification whatsoever to talk on art historyNext edit → | ||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

| {{quote|"It is part of the Turks’ holiness, also, that they tolerate no images or pictures and are even holier than our destroyers of images. For our destroyers tolerate, and are glad to have, images on gulden, groschen, rings, and ornaments; but the Turk tolerates none of them and stamps nothing but letters on his coins."|'']'' 1529 ]<ref></ref>}} | {{quote|"It is part of the Turks’ holiness, also, that they tolerate no images or pictures and are even holier than our destroyers of images. For our destroyers tolerate, and are glad to have, images on gulden, groschen, rings, and ornaments; but the Turk tolerates none of them and stamps nothing but letters on his coins."|'']'' 1529 ]<ref></ref>}} | ||

| ==Modern acknowledgments== | |||

| In a landmark speech at the ], the ] President ] acknowledged the Islamic contributions to civilization and Europe's Renaissance and Enlightenment: | |||

| {{quote|"As a student of history, I also know civilization's debt to Islam. It was Islam – at places like Al-Azhar – that carried the light of learning through so many centuries, paving the way for ]'s ] and ]. It was innovation in Muslim communities that developed the order of ]; our magnetic ] and tools of navigation; our mastery of pens and printing; our understanding of how disease spreads and how it can be healed. Islamic culture has given us majestic arches and soaring spires; timeless poetry and cherished music; elegant calligraphy and places of peaceful contemplation. And throughout history, Islam has demonstrated through words and deeds the possibilities of religious tolerance and racial equality".|], 4 June 2009, ].<ref></ref>}} | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 08:26, 13 November 2009

Left image: A "Bellini type" Islamic prayer rug, seen from the top, at the feet of the Virgin Mary, in Gentile Bellini's Madonna and Child Enthroned, late 15th century.

Left image: A "Bellini type" Islamic prayer rug, seen from the top, at the feet of the Virgin Mary, in Gentile Bellini's Madonna and Child Enthroned, late 15th century.Right image: Re-entrant prayer rug, Anatolia, late 15th to early 16th century.

Islamic influences on Christian art show multi-faceted contributions of Islamic art and culture in the achievements of Christian art. Most Christian arts have received such influence, from religious architecture to religious painting.

Influences on religious architecture

Carolingian architecture

Left image: Great Mosque of Córdoba.

Left image: Great Mosque of Córdoba.Right image: Horseshoe arches in the Palatine Chapel in Aachen. Further information: Abbasid-Carolingian alliance and Carolingian architecture

From Carolingian times, various Islamic influences seem to appear in Christian religious architecture such as the multi-colored tile designs which may have been inspired by Islamic polychromy in the 800 CE gatehouse at Lorsch Abbey.

Horseshoe arches, as well as the centralized plan, found in Carolingian churches such as Germigny-des-Prés suggest influence from the Mozarabic architectural designs of Islamic Spain. Early Carolingian architecture generally combines Roman, Early Christian, Byzantine, Islamic and Northern European designs.

Sicilian architecture

Islamic architecture also influenced the design of Christian buildings such as the Cappella Palatina in Palermo, Sicily, where a Arab-Norman culture particularly favoured syncretism. Especially, the ceilings and vault arches seem to have been inspired by the Islamic palaces of Fez and Fustat, and reflect the Muquarnas (stalactite) technique Islamic caligraphy was also used extensively in this type of architecture.

Gothic architecture

Further information: Gothic architecture

Throughout the Middle Ages, interactions between Christians, Muslims and Jews were numerous with considerable effect on the architecture of Western Europe. Especially, polychromy, the pointed arch and domes with interlacing ribs originated in mosque designs.

Techniques

The rib vault is also thought to have been derived from Islamic architecture: its technique goes back to the Romanesque period when it was adopted from Islamic architecture in Spain from the second half of the 10th century. The precise instance of transmission may relate to the Christian capture of Toledo in 1085 where some of the most beautiful examples of Islamic rib-vaults can be found, as the first experiments in rib-vaulting were started in Italy and England within 10 years of this event.

The pointed arch, developed in the Near East in the 8th century based on earlier Sasanian prototypes, is also thought to have spread from Islamic lands, possibly through Sicily, then under Islamic rule, and from there to Amalfi in Italy, before the end of the 11th century. The pointed arch then speedily spread through France in the 12th century.

The diaphragm arch is also considered as either Islamic or Late Antique in origin. The interior courtyard is also an Islamic adaptation.

The techniques of the rib-vault and the pointed arch reduced architectural thrust by about 20% and therefore proved a very attractive substitute to the Romanesque style for the building of large Christian structures. The weight of the rib vault was better channelled downard through pointed arches, diminishing the requirements for buttressing and giving a taller appearance to the structures.

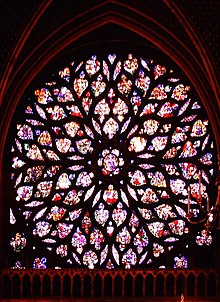

Stained glass is a common feature of mosques, and the Rose window may also have Islamic origins since the first known instance is from the Ummayad palace at Khirbat al-Mafjar, north of Jericho, but the route of transmission is unclear and independent development remains a possibility.

Evaluations

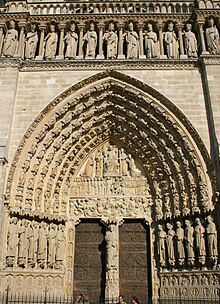

The Notre-Dame de Paris Gothic masterpiece for example integrates these numerous Islamic innovations. Despite these Romanesque and Islamic precedents however, Gothic architecture, called Opus Francigenum i.e. "French Work" in the Middle Ages and born in the area Ile-de-France around Paris in the 1130s, still represents a significant architectural breakthrough in itself, which succeeded in bringing astounding lightness to religious structures.

Scholars of the 18–19th century, who generally disliked the "disorder" of Gothic art and preferred Classical art, overstated the case, claiming that Gothic art fully originated in the Islamic art of the Mosque, to the point of calling it "Saracenical". William John Hamilton commented on the Seljuks monuments in Konya: "The more I saw of this peculiar style, the more I became convinced that the Gothic was derived from it, with a certain mixture of Byzantine (...) the origin of this Gotho-Saracenic style may be traced to the manners and habits of the Saracens" The 18th century English historian Thomas Warton would summarize:

"The marks which constitute the character of Gothic or Saracenical architecture, are, its numerous and prominent buttresses, its lofty spires and pinnacles, its large and ramified windows, its ornamental niches or canopies, its sculptured faints, the delicate lace-work of its fretted roofs, and the profusion of ornaments lavished indiscriminately over the whole building: but its peculiar distinguishing characteristics are, the small cluttered pillars and pointed arches, formed by the segments of two interfering circles"

— Thomas Warton Essays on Gothic architecture

Besides Islamic influences however, Gothic art also benefited from other influences such as Roman architectural techniques.

Islamic elements in Christian art

Islamic scripts and designs

Further information: Pseudo-Kufic

The Arabic Kufic script was often imitated in the West during the Middle-Ages and the Renaissance, to produce what is known as pseudo-Kufic: "Imitations of Arabic in European art are often described as pseudo-Kufic, borrowing the term for an Arabic script that emphasizes straight and angular strokes, and is most commonly used in Islamic architectural decoration". Numerous cases of pseudo-Kufic are known in European religious art from around the 10th to the 15th century. Pseudo-Kufic would be used as writing or as decorative elements in textiles, religious halos or frames. Many are visible in the paintings of Giotto.

Examples are known of the incorporation of Kufic script and Islamic-inspired colourful diamond-shaped designs such as a 13th French ciborium at the British Museum.

The exact reason for the incorporation of pseudo-Kufic in early Renaissance works is unclear. It seems that Westerners mistakenly associated 13–14th century Middle-Eastern scripts as being identical with the scripts current during Jesus's time, and thus found natural to represent early Christians in association with them: "In Renaissance art, pseudo-Kufic script was used to decorate the costumes of Old Testament heroes like David". Another reason might be that artists wished to express a cultural universality for the Christian faith, by blending together various written languages, at a time when the church had strong international ambitions.

Oriental carpets

Main article: Oriental carpets in Renaissance painting

Islamic carpets of Middle-Eastern origin, either from the Ottoman Empire, the Levant or the Mamluk state of Egypt or Northern Africa, were used as important decorative features in paintings from the 13th century onwards, and especially in religious painting, starting from the Medieval period and continuing into the Renaissance period.

Such carpets were often integrated into Christian imagery as symbols of luxury and status of Middle-Eastern origin, and together with Pseudo-Kufic script offer an interesting example of the integration of Eastern elements into European painting.

Islamic costumes

Islamic individuals and costumes often provided the contextual backdrop to describe an evangelical scene. This was particularly visible in a set of Venetian paintings in which contemporary Syrian, Palestinian, Egyptian and especially Mamluk personages are employed anachronistically in paintings describing Biblical situations. An example in point is the 15th century The Arrest of St. Mark from the Synagogue by Giovanni di Niccolò Mansueti which accurately describes contemporary (15th century) Alexandrian Mamluks arresting Saint Mark in an historic scene of the 1st century CE. Another case is Gentile Bellini's Saint Mark Preaching in Alexandria.

Book-binding designs

Elaborate bookbindings with Islamic designs have also often been used to convey knowledge in and express the study of Christian scriptures in religious paintings. In Andrea Mantegna's Saint John the Baptist and Zeno, Saint John and Zeno hold exquisite books with covers displaying Mamluk-style center-pieces, of a type also used in contemporary Italian book-binding.

Islam and Christian iconoclastic movements

Byzantine iconoclasm

Further information: Byzantine Iconoclasm

In the Byzantine Empire from 723 to 842, Islam and Judaism influenced a Christian movement towards the destruction of images this time, an event known as "Iconoclasm". According to Arnold Toynbee, it is the prestige of Islamic military successes in the 7–8th centuries that motivated Byzantine Christians into evaluating and adopting the Islamic precept of the destruction of idolatric images. Charlemagne himself attempted to follow the iconoclastic precepts of the East Roman Emperor Leo Syrus, but this effort was stopped by Pope Hadrian I.

Protestant iconoclasm

Further information: Islam and Protestantism and Reformation iconoclasm

With the criticizism of Catholicism and the advent of the Reformation in the 16th century, iconoclasm and the rejection of idols again became prominent in the awareness of those Christian who adopted Protestant ideas, and strongly influenced the evolution of Christian art in Protestant lands through the destruction of religious images.

The rejection of images, although more radical in the case of Islam, was understood as a common point in Protestantism and Islam: in the correspondence between Elizabeth I of England and her Ottoman Empire counterparts, she implied that Protestantism was closer to Islam than to Catholicism especially because of the rejection of idolatrous images. For critical purposes this time, the Catholics were in turn particularly keen to highlight the similarities between both types of iconoclasm, as indicative of a more fundamental connection between the two religions.

In On War against the Turk Martin Luther praised the Ottomans for their rigorous iconoclasm:

"It is part of the Turks’ holiness, also, that they tolerate no images or pictures and are even holier than our destroyers of images. For our destroyers tolerate, and are glad to have, images on gulden, groschen, rings, and ornaments; but the Turk tolerates none of them and stamps nothing but letters on his coins."

— On War against the Turk 1529 Martin Luther

See also

Notes

- A world history of architecture Marian Moffett p.194

- ^ A world history of architecture Marian Moffett p.195

- Medieval Italy: an encyclopedia by Christopher Kleinhenz p.835

- Encyclopedia of Arab American artists Fayeq Oweis p.33

- A world history of architecture Marian Moffett p.189

- A world history of architecture Marian Moffett p.189

- ^ Encountering the World of Islam Keith E. Swartley p.74

- ^ French Gothic Architecture of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries Jean Bony p.12-13

- ^ French Gothic Architecture of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries Jean Bony p.17ff

- Gardner's Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective Fred S. Kleiner p.342

- French Gothic Architecture of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries Jean Bony p.306

- Gardner's Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective Fred S. Kleiner p.342

- An Analysis and Brief History of the Three Great Monotheistic Faiths by Andrea C. Paterson p.135

- Islamic visual culture, 1100-1800 p.387 Oleg Grabar

- A history of Western architecture by David Watkin p.149

- Gardner's Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective Fred S. Kleiner p.340

- Researches in Asia Minor, Pontus and Armenia William John Hamilton p.206

- Oriental panorama: British travellers in 19th century Turkey Reinhold Schiffer p.141

- Essays on Gothic architecture by Thomas Warton p.14

- Mack, p.65-66

- ^ Mack, p.51

- British Museum exhibit

- Mack, p.52, p.69

- Freider. p.84

- "Perhaps they marked the imagery of a universal faith, an artistic intention consistent with the Church's contemporary international program." Mack, p.69

- ^ Mack, p.73-93

- ^ Mack, p.161

- Mack, p.164-65

- Mack, p.125-37

- Mack, p.127-28

- Byzantine iconoclasm

- Adventures in Paranormal Investigation Joe Nickell p.222

- ^ A Study of History: Abridgement of volumes VII-X by Arnold Joseph Toynbee p.259

- The birth and growth of Utrecht

- Adventures in Paranormal Investigation Joe Nickell p.222

- The age of wars of religion, 1000-1650 Cathal J. Nolan p.431

- Islam in Britain, 1558-1685 by Nabil I. Matar p.123

- Catholics Writing the Nation in Early Modern Britain and Ireland Christopher Highley p.62

- Works of Martin Luther by Martin Luther p.101

References

- Braden K. Frieder Chivalry & the perfect prince: tournaments, art, and armor at the Spanish Habsburg court Truman State University, 2008 ISBN 193111269X, ISBN 9781931112697

- Mack, Rosamond E. Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300-1600, University of California Press, 2001 ISBN 0520221311