| Revision as of 05:14, 29 December 2009 editWVBluefield (talk | contribs)750 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 05:17, 29 December 2009 edit undoWVBluefield (talk | contribs)750 edits incorporate some of IP's improvementsNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{pp-semi-protected|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Infobox Disease | {{Infobox Disease | ||

| |Name = Gulf War illness | |Name = Gulf War illness | ||

| |Image = Pyridostigmine.svg | |Image = Pyridostigmine.svg | ||

| |Caption = nerve agent antidote |

|Caption = Caption = pyridostigmine, a nerve agent antidote <br /> and one of the implicated toxins | ||

| |ICD9 = {{ICD9|V65.5}} (inconclusive) <br /> also nonstandard "DX111" | |ICD9 = {{ICD9|V65.5}} (inconclusive) <br /> also nonstandard "DX111" | ||

| |MeshID = D018923 | |MeshID = D018923 | ||

Revision as of 05:17, 29 December 2009

Medical condition| Gulf War syndrome |

|---|

Gulf War syndrome (GWS) or Gulf War illness (GWI) describes a range of illnesses reported by combat veterans of the 1991 Persian Gulf War typified by a range of medically unexplained symptoms. Symptoms attributed to this syndrome have been wide-ranging and include acute and chronic ailments. These include fatigue, loss of muscle control, headaches, dizziness and loss of balance, memory problems, muscle and joint pain, indigestion, skin problems.

Since the end of the Gulf War, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and the British Ministry of Defence have conducted numerous studies on Gulf War Veterans. The latest studies have determined that while the physical health of deployed veterans is similar to that of non-deployed veterans, there is an increase in 4 out of the 12 medical conditions reportedly associated with Gulf War syndrome While the exact source of veteran health complaints remains unknown, several possible causes have been investigated including post traumatic stress disorder, vaccinations, exposure to chemical weapons, smoke from oil well fires, pesticides, and depleted uranium.

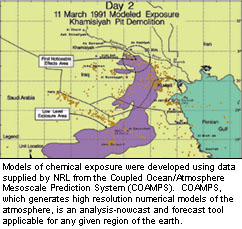

In the United States in 2008, the federally mandated Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans' Illnesses released a 452-page report indicating that roughly 1 in 4 of the 697,000 veterans who served in the first Gulf War are afflicted with the disorder. The report stated that "scientific evidence leaves no question that Gulf War illness is a real condition with real causes and serious consequences for affected veterans." , The report concluded that use of pyridostigmine bromide pills, given to protect troops from effects of nerve agents, and pesticide use during deployment were the two conditions most closely linked to illness . Researchers have also recently narrowed impaired neuropsychological function to individuals exposed to the destruction of the Khamisiyah weapons depot where large quantities of the neurotoxin Sarin was stored.

Classification

Medial ailments associated with Gulf War Syndrome has been recognized by both the US Department of Defense, Department of Veterans Affairs, and Veterans Administration. Since so little concrete information was known about this condition the Veterans administrations originally classified individuals with related ailments believed to be connected to their service in the Persian Gulf a special non-ICD-9 code DX111, as well as ICD-9 code V65.5.

Signs and symptoms

About one-fourth of the 697,000 U.S. servicemen and women in the first Gulf War have shown symptoms related to Gulf War Syndrome.

U.S. and UK, with the highest rates of excess illness, are distinguished from the other nations by higher rates of pesticide use, use of anthrax vaccine, and somewhat higher rates of exposures to oil fire smoke and reported chemical alerts. France, with possibly the lowest illness rates, had lower rates of pesticide use, and no use of anthrax vaccine. French troops also served to the North and West of all other combat troops, away and upwind of major combat engagements .

| Symptom | U.S. | UK | Australia | Denmark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | 23% | 23% | 10% | 16% |

| Headache | 17% | 18% | 7% | 13% |

| Memory problems | 32% | 28% | 12% | 23% |

| Muscle/joint pain | 18% | 17% | 5% | 2% (<2%) |

| Diarrhea | 16% | 9% | 13% | |

| Dyspepsia/indigestion | 12% | 5% | 9% | |

| Neurological problems | 16% | 8% | 12% | |

| Terminal tumors | 33% | 9% | 11% |

| Condition | U.S. | UK | Canada | Australia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin conditions | 20-21% | 21% | 4-7% | 4% |

| Arthritis/joint problems | 6-11% | 10% | (-1)-3% | 2% |

| Gastro-intestinal (GI) problems | 15% | 5-7% | 1% | |

| Respiratory problem | 4-7% | 2% | 2-5% | 1% |

| Chronic fatigue syndrome | 1-4% | 3% | 0% | |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 2-6% | 9% | 6% | 3% |

| Chronic multi-symptom illness | 13-25% | 26% |

A 2001 study of 15,000 February 1991 U.S. Gulf War combat veterans and 15,000 control veterans found that the Gulf War veterans were 1.8 (fathers) to 2.8 (mothers) times more likely to have children with birth defects.

Causes

The United States Congress mandated the National Academies of Science Institute of Medicine to provide nine reports on Gulf War Syndrome since 1998. Aside from the many physical and psychological issues involving any war zone deployment, Gulf War veterans were exposed to a unique mix of hazards not previously experienced during wartime. These included pyridostigmine bromide pills given to protect troops from the effects of nerve agents, depleted uranium munitions, and anthrax and botulinum vaccines. The oil and smoke that spewed for months from hundreds of burning oil wells presented another exposure hazard not previously encountered in a warzone. Military personnel also had to cope with swarms of insects, requiring the widespread use of pesticides.

United States Veterans Affairs Secretary Anthony Principi's panel found that pre-2005 studies suggested the veterans' illnesses are neurological and apparently are linked to exposure to neurotoxins, such as the nerve gas sarin, the anti-nerve gas drug pyridostigmine bromide, and pesticides that affect the nervous system. The review committee concluded that "Research studies conducted since the war have consistently indicated that psychiatric illness, combat experience or other deployment-related stressors do not explain Gulf War veterans illnesses in the large majority of ill veterans," the review committee said.

Pyridostigmine bromide nerve gas antidote

The US military issued pyridostigmine bromide pills, PB, to protect against exposure to nerve gas agents such as sarin and soman. PB was used to pretreat nerve agent poisoning and is not a vaccine however taken before exposure to nerve agents, PB was thought to increase the efficacy of nerve agent antidotes. PB had been used since 1955 for patients suffering from myasthenia gravis with dosed up to 1,500 mg a day, far in excess of the 90 mg given to soldiers, and was considered safe by the FDA at either level for indefinite use and its use to pretreat nerve agent exposure has recently been approved.

About half of U.S. Gulf War veterans report using PB during deployment, with greatest use among Army personnel. Concerns have been raised about the possibility of increased health problems from PB when it is combined with other risk factors.

Given both the large body of epidemiological data on myasthenia gravis patients and follow up studies done on veterans it was concluded that while it was unlikely that health effects reported today by Gulf War veterans are the result of exposure solely to PB, use of PB was causally associated with illness.

Organophosphate pesticides

The use of organophosphate pesticides and insect repellants during the first Gulf War is credited with keeping rates of pest-borne diseases low. Pesticide use is one of only two exposures consistently identified by Gulf War epidemiologic studies to be significantly associated with Gulf War illness. Multisymptom illness profiles similar to Gulf War illness have been associated with low-level pesticide exposures in other human populations. In addition, Gulf War studies have identified dose-response effects, indicating that greater pesticide use is more strongly associated with Gulf War illness than more limited use. Pesticide use during the Gulf War has also been associated with neurocognitive deficits and neuroendocrine alterations in Gulf War veterans in clinical studies conducted follownf the end of the war. The 2008 report concluded that “all available sources of evidence combine to support a consistent and compelling case that pesticide use during the Gulf War is causally associated with Gulf War illness.”

Sarin nerve agent

Many of the symptoms of Gulf War syndrome are similar to the symptoms of organophosphate, mustard gas, and nerve gas poisoning. Gulf War veterans were exposed to a number of sources of these compounds, including nerve gas and pesticides.

Chemical detection units from the Czech Republic, France, and Britain confirmed chemical agents. French detection units detected chemical agents. Both Czech and French forces reported detections immediately to U.S. forces. U.S. forces detected, confirmed, and reported chemical agents; and U.S. soldiers were awarded medals for detecting chemical agents. The Riegle Report said that chemical alarms went off 18,000 times during the Gulf War. After the air war started on January 16, 1991, coalition forces were chronically exposed to low but nonlethal levels of chemical and biological agents released primarily by direct Iraqi attack via missiles, rockets, artillery, or aircraft munitions and by fallout from allied bombings of Iraqi chemical warfare munitions facilities.

In 1997, the US Government released an unclassified report that stated, "The US Intelligence Community (IC) has assessed that Iraq did not use chemical weapons during the Gulf War. However, based on a comprehensive review of intelligence information and relevant information made available by the United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM), we conclude that chemical warfare (CW) agent was released as a result of US postwar demolition of rockets with chemical warheads at several sites including Khamisiyah". Over 125,000 U.S. troops and 9,000 UK troops were exposed to nerve gas and mustard gas when the Iraqi depot in Khamisiyah was destroyed . "

Recent studies have confirmed earlier suspicions that exposure that sarin, in combination with other contaminants such as pesticides and PB were related to reports of veteran illness. Estimates range from 100,000 to 300,000 individuals exposed to nerve agents

Depleted uranium

Depleted uranium (DU) was widely used in tank kinetic energy penetrator and autocannon rounds for the first time in the Gulf War. DU is a dense, weakly radioactive metal with physical properties that make it particularly useful in weapons. Munitions often burn when they impact a hard target, producing toxic combustion products. Roughly 320 tons of DU were used during the conflict. After military personnel began reporting unexplained health problems in the aftermath of the Gulf War, questions were raised about the health effect of exposure to depleted uranium.

Sandia National Laboratory commissioned a two year study on the health effects of depleted uranium exposure during the Gulf War. The study found no epidemiological evidence for increase in birth defects and that claims of adverse chronic health risks from DU exposure were not supported follow up studies on veterans. A RAND Corporation study concluded that the evidence does not suggest long-term excess morbidity or mortality for DU exposure found in veterans.

The 2008 Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses similarly concluded that while there were unanswered questions about the long term effects of DU exposure, it was not likely a primary cause of Gulf War Syndrome.

Anthrax vaccine

Iraq had loaded anthrax, botulinum toxin, and aflatoxin into missiles and artillery shells in preparing for the Gulf War and that these munitions were deployed to four locations in Iraq. During Operation Desert Storm, 41% of U.S. combat soldiers and 75% of UK combat soldiers were vaccinated against anthrax. Like all vaccines, the early 1990s version of the anthrax vaccine was a source of several side effects. Reactions included local skin irritation, some lasting for weeks or months. While the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the vaccine, it never went through large scale clinical trials, unlike most other vaccines in the United States. While recent studies have demonstrated the vaccine’s is highly reactogenic , there is no clear evidence or epidemiological studies on Gulf War veterans linking the vaccine to Gulf War Syndrome. Combining this with the lack of symptoms from current deployments of individuals who have received the vaccine led the Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses to conclude that the vaccine is not a likely cause of Gulf War illness for most ill veterans.

Combat stress

Research studies conducted since the war have consistently indicated that psychiatric illness, combat experience or other deployment-related stressors do not explain Gulf War veterans illnesses in the large majority of ill veterans, according to a Veterans Administration review committee.

Oil well fires

During the war, many oil wells were set on fire in Kuwait by the retreating Iraqi army, and the smoke from those fires was inhaled by large numbers of soldiers, many of whom suffered acute pulmonary and other chronic effects, including asthma and bronchitis. However, firefighters who were assigned to the oil well fires and encountered the smoke, but who did not take part in combat, have not had GWI symptoms.

Management

Diplomatic reconciliation is one means of prevention, beyond battlefield air quality management, which often conflicts with established tactical policy. For example, most organized armies practice "secure and hold" tactics which require occupation of areas before they can be decontaminated.

In 2008, a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggested that excess illnesses in Gulf War veterans could be explained in part by their exposure to organophosphate and carbamate acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. A federal report released in November, 2008, agreed, stating that exposure to two substances "are causally associated with Gulf War illness":

- pyridostigmine bromide, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor intended to protect against nerve agents, and

- pesticides and insect repellents (often acetylcholinesterase inhibitors)

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2009) |

Epidemiology

Epidemiologic studies have been performed evaluating many suspected factors for Gulf War illness as seen in veteran populations. Below is a summary of epidemiologic studies of veterans displaying multisymptom illness and their exposure to suspect conditions from the 2008 U.S. Veterans Administration report.

| Epidemiologic Studies of Gulf War Veterans: Association of Deployment Exposures With Multisymptom Illness | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preliminary Analysis (no controls for exposure) | Adjusted Analysis (controlling for effects of exposure) | Clinical Evaluations | |||||

| GWV population in which association was assessed | GWV population in which association was statistically significant | GWV population in which association was assessed | GWV population in which association was statistically significant | Dose response effect identified? | |||

| Pyridostigmine bromide | 10 | 9 | 6 | 6 | ✓ | Associated with neurocognitive and HPA differences in GW vets | |

| Pesticides | 10 | 10 | 6 | 5 | ✓ | Associated with neurocognitive and HPA differences in GW vets | |

| Physiological Stressors | 14 | 13 | 7 | 1 | |||

| Chemical Weapons | 16 | 13 | 5 | 3 | Associated with neurocognitive and HPA differences in GW vets | ||

| Oil Well Fires | 9 | 8 | 4 | 2 | ✓ | ||

| Number of Vaccines | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ✓ | ||

| Anthrax Vaccine | 5 | 5 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Tent Heater Exhaust | 5 | 4 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Sand/Particulates | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | |||

| Depleted Uranium | 5 | 3 | 1 | 0 | |||

Controversy

Similar syndromes have been seen as an after effect of other conflicts — for example, 'shell shock' after World War I, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after the Vietnam War. A review of the medical records of 15,000 American Civil War soldiers showed that "those who lost at least 5% of their company had a 51% increased risk of later development of cardiac, gastrointestinal, or nervous disease."

A November 1996 article in the New England Journal of Medicine found no difference in death rates, hospitalization rates or self-reported symptoms between Persian Gulf veterans and non-Persian Gulf veterans. This article was a compilation of dozens of individual studies involving tens of thousands of veterans. The study did find a statistically significant elevation in the number of traffic accidents suffered by Gulf War veterans. An April, 1998 article in Emerging Infectious Diseases similarly found no increased rate of hospitalization and better health overall for veterans of the Persian Gulf War vs. Veterans who stayed home.

Despite these studies, on November 17, 2008 a congressionally appointed committee called the Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans' Illnesses, staffed with independent scientists and veterans appointed by the Department of Veterans Affairs, announced that the syndrome is a distinct physical condition. The committee recommended that Congress increase funding for research on Gulf War veterans' health to at least $60 million per year. In January 2006, a study led by Melvin Blanchard and published by the Journal of Epidemiology, part of the "National Health Survey of Gulf War-Era Veterans and Their Families", stated that veterans deployed in the Persian Gulf War had nearly twice the prevalence of chronic multisymptom illness, a cluster of symptoms similar to a set of conditions often called Gulf War Syndrome.

See also

- Beyond Treason an 89-minute 2005 documentary that covers the Gulf War syndrome.

- Environmental issues with war

References

- Iversen A, Chalder T, Wessely S. "Gulf War Illness: lessons from medically unexplained symptoms." Clin Psychol Rev. 2007 Oct;27(7):842-54.

- Gronseth GS. "Gulf war syndrome: a toxic exposure? A systematic review." Neurol Clin. 2005 May;23(2):523-40.

- University of Virginia. Gulf War Syndrome

- Annals of Internal Medicine. Gulf War Veterans' Health: Medical Evaluation of a U.S. Cohort. June 7, 2005

- ^ Gulf War Illness and Health of Gulf War Veterans

- Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. Neuropsychological functioning of U.S. Gulf War veterans 10 years after the war.

- Gulf War Veterans' Illnesses: Illnesses Associated with Gulf War Service

- Department of Veterans Affairs A Guide to Gulf War Veterans' Health

- Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses December 12-13, 2005 Committee Meeting Minutes (page 78)

- Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses December 12-13, 2005 Committee Meeting Minutes (page 68)

- Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses December 12-13, 2005 Committee Meeting Minutes (page 70), This table applies only to coalition forces involved in combat.

- Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses December 12-13, 2005 Committee Meeting Minutes (page 71)

- Kang, H.; et al. (2001). "Pregnancy Outcomes Among U.S. Gulf War Veterans: A Population-Based Survey of 30,000 Veterans". Annals of Epidemiology. 11 (7): 504–511. doi:10.1016/S1047-2797(01)00245-9. PMID 11557183.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help) - VA Press Release

- Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses 2004 Report

- PBS Frontline. PYRIDOSTIGMINE BROMIDE Use in the First Gulf War

- U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Special Assistant to the Undersecretary of Defense (Personnel and Readiness) for Gulf War Illnesses Medical Readiness and Military Deployments. Environmental Exposure Report: Pesticides Final Report. Washington, D.C. April 17, 2003.

- Krengel M, Sullivan K. Neuropsychological Functioning in Gulf War Veterans Exposed to Pesticides and Pyridostigmine Bromide. Fort Detrick, MD: U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command; August, 2008. W81XWH-04-1-0118

- Friis, Robert H. (2004). Epidemiology for Public Health Practice. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 0763731706.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Spektor, Dalia M. (1998). A Review of the Scientific Literature as it Pertains to Gulf War Illnesses. Rand Corporation. ISBN 0833026801.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "Campaigners hail 'nerve gas link' to Gulf War Syndrome - Scotsman.com News". News.scotsman.com. Retrieved 2009-11-24.

- The Riegle Report

- Khamisiyah: A Historical Perspective on Related Intelligence by the Persian Gulf War Illnesses Task Force (9 April 1997)

- Beatrice Alexandra Golomb.Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and Gulf War illnesses

- Navy Times. Review says chemicals caused Gulf War illness

- Global Security. ``Depleted Uranium``

- Al Marshal, Sandia National Laboratory. An Analysis of Uranium Dispersal and Health Effects Using a Gulf War Case Study, Albert C. Marshall, Sandia National Laboratories

- Harley NH, Foulkes EC, Hilborne LH, Hudson A, Anthony CR. A Review of the Scientific Literature As It Pertains to Gulf War Illnessess: Depleted Uranium. Vol 7. Arlington, VA: National Defense Research Institute (RAND); 1999

- Anthony H. Cordesman. Iraq and the War of Sanctions: Conventional Threats and Weapons of Mass Destruction

- Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses December 12-13, 2005 Committee Meeting Minutes (page 73.)

- GAO-01-92T Anthrax Vaccine: Preliminary Results of GAO's Survey of Guard/Reserve Pilots and Aircrew Members

- The Clarion-Ledger: Mississippi's News Source

- Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety.Short-term reactogenicity and gender effect of anthrax vaccine: analysis of a 1967-1972 study and review of the 1955-2005 medical literature

- Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses December 12-13, 2005 Committee Meeting Minutes (pages 148, 154, 156)

- Curle, A. (1997) "Public mental health. III: Hatred and reconciliation." Med Confl Surviv 13(1):37-47. PMID 9080785

- ^ Jentleson, B.W. (1996) "Preventive Diplomacy and Ethnic Conflict: Possible, Difficult, Necessary" UC Berkeley Policy Paper 27, Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation

- Golomb, B. (2008) "Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and Gulf War illnesses" Proc Natl Acad Sci; Reuters; MedPageToday.com

- "Gulf War illness is real, new federal report says" on CNN

- Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses December 12-13, 2005 Committee Meeting Minutes

- Gulf War Illness and Health of Gulf War Veterans (page 220-221)

- Gulf War Illness and Health of Gulf War Veterans (page 222)

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1126/science.291.5505.812, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1126/science.291.5505.812instead. - New England Journal of Medicine. Disease and Suspicion after the Persian Gulf War. Volume 335:1525-1527, November 14, 1996

- Knoke JD, Gray GC (1998). "Hospitalizations for unexplained illnesses among U.S. veterans of the Persian Gulf War" (PDF). Emerging Infect. Dis. 4 (2): 211–9. PMC 2640148. PMID 9621191.

- News Services, "Gulf War Syndrome Is Real, Panel Concludes", Washington Post, November 18, 2008, p. 14.

- Record: Study finds multisymptom condition is more prevalent among Persian Gulf vets

External links

- Research

- Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans' Illnesses, publishers of the 2008 Gulf War Illness and the Health of Gulf War Veterans: Scientific Findings and Recommendations (7.4 MB PDF)

- Associations