| Revision as of 16:53, 21 January 2010 editHeadbomb (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, File movers, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers, Template editors454,149 edits bibcodes← Previous edit | Revision as of 18:06, 21 January 2010 edit undoShocking Blue (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers3,726 editsm Typo.Next edit → | ||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

| |bibcode=1864RSPT..154..437H | |bibcode=1864RSPT..154..437H | ||

| |id={{JSTOR|108876}} | |id={{JSTOR|108876}} | ||

| }}</ref> These lines did not correspond to any known elements on Earth. The fact that ] had been identified by the |

}}</ref> These lines did not correspond to any known elements on Earth. The fact that ] had been identified by the emission lines in the Sun in 1868 and in 1895 had also been found on Earth encouraged astronomers to suggest that the lines were due to a new element. The name '''nebulium''' was first mentioned by the wife of Huggins in a short communication in 1898, although it is stated that Huggins occasionally used the term before.<ref> | ||

| {{cite journal | {{cite journal | ||

| |title = .... Teach me how to name the .... light, | |title = .... Teach me how to name the .... light, | ||

Revision as of 18:06, 21 January 2010

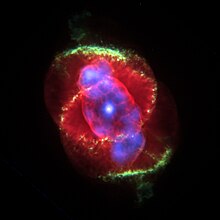

Nebulium was a proposed element found in a nebula by William Huggins in 1864. The strong green emission lines of the Cat's Eye Nebula, discovered using spectroscopy, led to the postulation that an as yet unknown element was responsible for this emission. In 1927, Ira Sprague Bowen showed that the lines are emitted by doubly ionized oxygen, and no new element was necessary to explain them.

History

William Hyde Wollaston in 1802 and Joseph von Fraunhofer in 1814 described the dark lines within the solar spectrum. Later, Gustav Kirchhoff explained the lines by atomic absorption or emission that allowed to use them for the identification of chemical elements.

In the early days of telescopic astronomy, the word nebula was used to describe any fuzzy patch of light that did not look like a star. Many of these, such as the Andromeda Nebula, had spectra that looked in many ways a lot like stellar spectra, and these turned out to be galaxies. Others, such as the Cat's Eye Nebula, had very different spectra. When William Huggins looked at the Cat's Eye, he found no continuous spectrum like that seen in the Sun, but just a few strong emission lines. The two green lines at 4959 and 5007 ångströms were the strongest. These lines did not correspond to any known elements on Earth. The fact that helium had been identified by the emission lines in the Sun in 1868 and in 1895 had also been found on Earth encouraged astronomers to suggest that the lines were due to a new element. The name nebulium was first mentioned by the wife of Huggins in a short communication in 1898, although it is stated that Huggins occasionally used the term before. (nebulium, occasionally nebulum or nephelium). The development of the periodic table by Dimitri Mendeleev and the determination of the atomic numbers by Henry Moseley in 1913, left nearly no room for a new element.

Ira Sprague Bowen was working on UV spectroscopy and on the calculation of spectra of the light elements of the periodic table when he became aware of the green lines discovered by Huggins. With this knowledge he was able to suggest that the green lines might be forbidden transition, and so the hypothetical nebulium that was invoked to account for certain bright lines in gaseous nebulae were shown as due to doubly ionized oxygen at extremely low density. As Henry Norris Russell put it, "Nebulium has vanished into thin air." Nebulae are typically extremely rarefied, much less dense than the hardest vacuum ever produced on Earth. In these conditions, atoms behave quite differently, and lines can form which are suppressed at normal densities. These lines are known as forbidden lines, and are the strongest lines in most nebular spectra.

References

- W. Huggins, W.A. Miller (1864). "On the Spectra of some of the Nebulae". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 154: 437–444. Bibcode:1864RSPT..154..437H. JSTOR 108876.

- M.L. Huggins (1898). ".... Teach me how to name the .... light,". Astrophysical Journal. 8: 54–54. Bibcode:1898ApJ.....8R..54H. doi:10.1086/140540.

- I.S. Bowen (1927). "The Origin of the Nebulium Spectrum". Nature. 120: 473. doi:10.1038/120473a0.

- R.F. Hirsh (1979). "The Riddle of the Gaseous Nebulae". Isis. 70 (2): 197–212. Bibcode:1979Isis...70..197H. JSTOR 230787.