| Revision as of 02:37, 9 March 2010 editTb (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers7,495 editsm Reverted edits by 98.26.103.228 (talk) to last version by D'ohBot← Previous edit | Revision as of 13:05, 5 May 2010 edit undo81.171.233.243 (talk) →Essential texts: Edited for a more neutral point of view.Next edit → | ||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

| * ] collection of texts. | * ] collection of texts. | ||

| There are also ''The Conferences'' and ''The Institutes'' by Cassian, |

There are also the large and detailed ''The Conferences'' and ''The Institutes'' by Cassian, considered to be rather scholarly volumes though of the time. | ||

| ]'s |

]'s book ''The Wisdom of the Desert'' is a selection from the Sayings of the Desert Fathers, and includes his introduction. | ||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

Revision as of 13:05, 5 May 2010

The Desert Fathers were Hermits, Ascetics and Monks who lived mainly in the Scetes desert of Egypt, beginning around the third century. They were the first Christian hermits, who abandoned the cities of the pagan world to live in solitude. These original desert hermits were Christians fleeing the chaos and persecution of the Roman Empire's Crisis of the Third Century. They were men who did not believe in letting themselves be passively guided and ruled by a decadent state. Christians were often scapegoated during these times of unrest, and near the end of the century, the Diocletianic Persecution was more severe and systematic. In Egypt, refugee communities formed at the edges of population centers, far enough away to be safe from Imperial scrutiny.

In 313, when Christianity was made legal in Egypt by Diocletian's successor Constantine I, a trickle of individuals, many of them young men, continued to live in these marginal areas. The solitude of these places attracted them because the privations of the desert were a means of learning stoic self-discipline. Such self-discipline was modelled after the examples of Jesus' fasting in the desert and of his cousin John the Baptist (himself a desert hermit). These individuals believed that desert life would teach them to eschew the things of this world and allow them to follow God's call in a more deliberate and individual way.

Thus, during the fourth century, the empty areas around Egyptian cities continued to attract others from the world over, wishing to live in solitude. As the lifestyle developed, these men and women developed a reputation for holiness and wisdom. In its early form, each hermit followed more or less an individual spiritual program, perhaps learning some basic practices from other monks, but developing them into their own unique (and sometimes highly idiosyncratic) practice. Later monks, notably Anthony the Great, Pachomius and Shenouda the Archimandrite, developed a more regularized approach to desert life, and introduced some aspects of community living (especially common prayer and meals) that would eventually develop into cenobitic monasticism. Many individuals who spent part of their lives in the Egyptian desert went on to become important figures in the Church and society of the fourth and fifth century, among them Athanasius of Alexandria, John Chrysostom, and John Cassian. Through the work of the John Cassian and Augustine of Hippo the spirituality of the desert fathers, emphasizing an ascent to God through periods of purgation and illumination that led to unity with the Divine, deeply affected the spirituality of the Western Church and the Eastern Church. For this reason, the writings and spirituality of the desert fathers are still of interest to many people today.

Philosophy

No Christian state

Even after Christianity became a legal religion of the Roman Empire in 313, the fact that the Emperor could now be a Christian and that the world was coming to know Christianity and the Cross as a sign of temporal power only strengthened the hermits' resolve. For the hermits there was really no such thing as a "Christian" state. They doubted the fact that religion and politics could ever be mixed to such an extent as to produce a fully Christian society. For them the only Christian society was spiritual and extramundane.

Primacy of love

In the sayings of the Desert Fathers, there was insistence on the primacy of love over everything else in spiritual life, over knowledge, gnosis, asceticism, contemplation, solitude, prayer. Without love the exercises of the spirit lose all meaning. Their idea of love was not sentiment but spiritual identification with one's brother; taking one's neighbor as one's self. The full difficulty and magnitude of the task of loving others is recognized everywhere and never minimized. They understood that it is very hard to love others in the full sense of the word and that it involved a kind of death of their own being.

Purity of heart

The basic principle of the Desert Life was that God is the Authority and that apart from His manifest will there are few or no principles. St. Anthony said,. "therefore whatever you see your soul to desire according to God, do that thing, and you shall keep your heart safe." The Desert life started out with a clean break from the world. A life continued in compunction which taught the monk to lament the attachment to unreal values. The Desert Fathers lived a life of solitude, labour, poverty, fasting, charity and prayer. This purging allowed for the emergence of the true secret self in which the believer and Christ were "one spirit." The end of all striving was purity of heart which culminated in a clear unobstructed vision of the true state of affairs and an intuitive grasp of one's inner reality anchored in God. Many of the desert fathers and mothers found "true peace", just as the Theotokos in a vision said that the repenting St. Mary of Egypt should find, if she crossed the river Jordan. She then also became a hermit in the desert, nearby Jordan. That was in the 5th century.

Some Sayings of the Desert Fathers

One of the Elders, "It is not because of evil thoughts that we are condemned, but only because we make use of these evil thoughts."

Abbot Pastor, "If someone does evil to you, you should do good to him, so that by your good work you may drive out his malice."

An Elder, "A man who keeps death before his eyes will at all times overcome his cowardliness."

Blessed Macarius said, "This is the truth, if a monk regards contempt as praise, poverty as riches, and hunger as a feast, he will never die."

Abba Moses, "Sit in thy cell and thy cell will teach thee all."

Essential texts

The essential texts — from the time itself — are:

- The Sayings of the Desert Fathers (Apophthegmata Patrum) translated by Benedicta Ward, with an introduction;

- The Lives of the Desert Fathers translated by Norman Russell, with a highly informative introduction;

- The Lausiac History by Palladius;

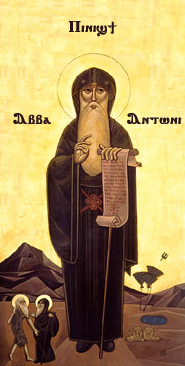

- The Life of Saint Antony by St. Athanasius.

- Philokalia collection of texts.

There are also the large and detailed The Conferences and The Institutes by Cassian, considered to be rather scholarly volumes though of the time.

Thomas Merton's book The Wisdom of the Desert is a selection from the Sayings of the Desert Fathers, and includes his introduction.