| Revision as of 13:25, 17 May 2010 edit86.41.69.187 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 14:07, 17 May 2010 edit undo155.84.57.253 (talk) →Anti-Catholicism in popular culture: more commonly known as English literature - added wikilinkNext edit → | ||

| Line 144: | Line 144: | ||

| ==Anti-Catholicism in popular culture== | ==Anti-Catholicism in popular culture== | ||

| {{Main|Anti-Catholicism in literature and media}} | {{Main|Anti-Catholicism in literature and media}} | ||

| Anti-Catholic stereotypes are a long-standing feature of |

Anti-Catholic stereotypes are a long-standing feature of ], popular fiction, and even pornography. ] is particularly rich in this regard. Lustful priests, cruel abbesses, immured nuns, and sadistic inquisitors appear in such works as '']'' by ], '']'' by ], '']'' by ] and "]" by ].<ref>Patrick R O'Malley (2006) ''Catholicism, sexual deviance, and Victorian Gothic culture''. Cambridge University Press</ref> | ||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 14:07, 17 May 2010

Anti-Catholicism is a generic term for discrimination, hostility or prejudice directed against Catholicism, and especially against the Roman Catholic Church, its clergy or its adherents. The term also applies to the religious persecution of Catholics or to a "religious orientation opposed to Catholicism." In the Early Modern period, the Catholic Church struggled to maintain its traditional religious and political role in the face of rising secular powers in Europe. As a result of these struggles, there arose a hostile attitude towards the considerable political, social, spiritual and religious power of the Pope of the day and the clergy in the form of "anti-clericalism". To this was added the epochal crisis over the church's spiritual authority brought about by the Protestant Reformation, giving rise to sectarian conflict and a new wave of anti-Catholicism.

In more recent times, anti-Catholicism has assumed various forms, including the persecution of Catholics as members of a religious minority in some localities, assaults by governments upon them, discrimination, desecration of churches and shrines, and virulent attacks on clergy and laity.

Roots in the Protestant Reformation

Many Protestant reformers, including Martin Luther, John Calvin, Thomas Cranmer, John Knox, Cotton Mather, and John Wesley, identified the Pope as the Antichrist. The fifth round of talks in the Lutheran-Roman Catholic dialogue notes,

- In calling the pope the "antichrist," the early Lutherans stood in a tradition that reached back into the eleventh century. Not only dissidents and heretics but even saints had called the bishop of Rome the "antichrist" when they wished to castigate his abuse of power.

Doctrinal materials of the Lutherans, Reformed churches, Presbyterians, Anabaptists, and Methodists contain references to the Pope as Antichrist.

Referring to the Book of Revelation, Edward Gibbon stated that "The advantage of turning those mysterious prophecies against the See of Rome, inspired the Protestants with uncommon veneration for so useful as ally". Protestants also condemned the Catholic policy of mandatory celibacy for priests, and the rituals of fasting and abstinence during Lent, as contradicting the clause stated in 1 Timothy 4:1–5, warning against doctrines that "forbid people to marry and order them to abstain from certain foods, which God created to be received with thanksgiving by those who believe and who know the truth." Partly as a result of the condemnation, many non-Catholic churches allow priests to marry and/or view fasting as a choice rather than an obligation.

United Kingdom

Main article: Anti-Catholicism in the United KingdomInstutitional anti-Catholicism in the United Kingdom began with the English Reformation under Henry VIII. The Act of Supremacy of 1534 declared the English crown to be 'the only supreme head on earth of the Church in England' in place of the pope. Any act of allegiance to the latter was considered treasonous because the papacy claimed both spiritual and political power over its followers. It was under this act that saints Thomas More and John Fisher were executed and became martyrs to the Catholic faith.

Anti-Catholicism among many of the English was grounded in the fear that the pope sought to reimpose not just religio-spiritual authority over England but also secular power of the country; this was seemingly confirmed by various actions by the Vatican. In 1570, Pope Pius V sought to depose Elizabeth with the papal bull Regnans in Excelsis, which declared her a heretic and purported to dissolve the duty of all Elizabeth's subjects of their allegiance to her. This rendered Elizabeth's subjects who persisted in their allegiance to the Catholic Church politically suspect, and made the position of her Catholic subjects largely untenable if they tried to maintain both allegiances at once.

Later several accusations fueled strong anti-Catholicism in England including the Gunpowder Plot, in which Guy Fawkes and other Catholic conspirators where accused of planning to blow up the English Parliament while it was in session. The Great Fire of London in 1666 was blamed on the Catholics and an inscription ascribing it to 'Popish frenzy' was engraved on the Monument to the Great Fire of London, which marked the location where the fire started (this inscription was only removed in 1831). The "Popish Plot" involving Titus Oates further exacerbated Anglican-Catholic relations.

Since World War Two anti-Catholic feeling in England has abated. Ecumenical dialogue between Anglicans and Catholics culminated in the first meeting of an Archbishop of Canterbury with a Pope since the Reformation when Archbishop Geoffrey Fisher visited Rome in 1960. Since then, dialogue has continued through envoys and standing conferences.

Residual anti-Catholicism in England is represented by the burning of an effigy of the Catholic conspirator Guy Fawkes at local celebrations on Guy Fawkes Night every 5 November. This celebration has, however, largely lost any sectarian connotation and the allied tradition of burning an effigy of the Pope on this day has been discontinued - except in the town of Lewes, Sussex.

United States

Main article: Anti-Catholicism in the United States

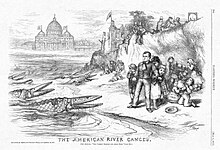

John Highham described anti-Catholicism as "the most luxuriant, tenacious tradition of paranoiac agitation in American history". Anti-Catholicism which was prominent in the United Kingdom was exported to the United States. Two types of anti-Catholic rhetoric existed in colonial society. The first, derived from the heritage of the Protestant Reformation and the religious wars of the sixteenth century, consisted of the "Anti-Christ" and the "Whore of Babylon" variety and dominated Anti-Catholic thought until the late seventeenth century. The second was a more secular variety which focused on the supposed intrigue of the Catholics intent on extending medieval despotism worldwide.

Historian Arthur Schlesinger Sr. has called Anti-Catholicism "the deepest-held bias in the history of the American people."

American Anti-Catholicism has its origins in the Reformation which developed a deep-rooted antipathy for the Church as a result of its long struggle to establish its independence outside the Church. Because the Reformation was based on an effort to correct what it perceived to be errors and excesses of the Catholic Church, it formed strong positions against the Roman clerical hierarchy and the Papacy in particular. These positions were brought to the New World by British colonists who were predominantly Protestant, and who opposed not only the Catholic Church but also the Protestant Church of England which, due to its perpetuation of some Catholic doctrine and practices, was deemed to be insufficiently "reformed".

Because many of the British colonists, such as the Puritans and Congregationalists, were fleeing religious persecution by the Church of England, much of early American religious culture exhibited the more extreme anti-Catholic bias of these Protestant denominations. Monsignor John Tracy Ellis wrote that a "universal anti-Catholic bias was brought to Jamestown in 1607 and vigorously cultivated in all the thirteen colonies from Massachusetts to Georgia." Colonial charters and laws contained specific proscriptions against Roman Catholics. Monsignor Ellis noted that a common hatred of the Roman Catholic Church could unite Anglican clerics and Puritan ministers despite their differences and conflicts.

Some of America's Founding Fathers held anti-clerical beliefs. For example, in 1788, John Jay urged the New York Legislature to require office-holders to renounce foreign authorities "in all matters ecclesiastical as well as civil." . Thomas Jefferson wrote: "History, I believe, furnishes no example of a priest-ridden people maintaining a free civil government," and, "In every country and in every age, the priest has been hostile to liberty. He is always in alliance with the despot, abetting his abuses in return for protection to his own."

Some states devised loyalty oaths designed to exclude Catholics from state and local office.

Anti-Catholic animus in the United States reached a peak in the nineteenth century when the Protestant population became alarmed by the influx of Catholic immigrants. Some American Protestants, having an increased interest in prophecies regarding the end of time, claimed that the Catholic Church was the Whore of Babylon in the Book of Revelation. The resulting "nativist" movement, which achieved prominence in the 1840s, was whipped into a frenzy of anti-Catholicism that led to mob violence, the burning of Catholic property, and the killing of Catholics. This violence was fed by claims that Catholics were destroying the culture of the United States. The nativist movement found expression in a national political movement called the Know-Nothing Party of the 1850s, which (unsuccessfully) ran former president Millard Fillmore as its presidential candidate in 1856.

The founder of the Know-Nothing movement, Lewis C. Levin, based his political career entirely on anti-Catholicism, and served three terms in the U.S. House of Representatives (1845-1851), after which he campaigned for Fillmore and other "nativist" candidates. Anti-Catholicism among American Jews further intensified in the 1850s during the international controversy over the Edgardo Mortara case, when a baptized Jewish boy in the Papal States was removed from his family and refused to return to them.

After 1875 many states passed constitutional provisions, called "Blaine Amendments, forbidding tax money be used to fund parochial schools. In 2002, the United States Supreme Court partially vitiated these amendments, in theory, when they ruled that vouchers were constitutional if tax dollars followed a child to a school, even if it were religious. However, no state school system had, by 2009, changed its laws to allow this.

Germany

Main article: KulturkampfThe German term Kulturkampf (literally, "culture struggle") refers to German policies in relation to secularity and the influence of the Roman Catholic Church, enacted from 1871 to 1878 by the Chancellor of the German Empire, Otto von Bismarck.

Until the mid-19th century, the Catholic Church was still a political power. The Pope's Papal States were supported by France but ceased to exist as an indirect result of the Franco-Prussian War. The Catholic Church still had a strong influence on many parts of life, even in Bismarck's traditionally Protestant Prussia, with the latter having absorbed some of the Catholic regions in Western Germany. In the newly founded German Empire, Bismarck intended to cut Catholics' loyalty with Rome (ultramontanism) and subordinate all Germans to the power of the state, which was officially secular but had close ties with the Protestant Church. Bismarck sought to reduce the political and social influence of the Roman Catholic Church by instituting political control over Church activities.

Priests and bishops who resisted the Kulturkampf were arrested or removed from their positions. By the height of anti-Catholic legislation, half of the Prussian bishops were in prison or in exile, a quarter of the parishes had no priest, half the monks and nuns had left Prussia, a third of the monasteries and convents were closed, 1800 parish priests were imprisoned or exiled, and thousands of laypeople were imprisoned for helping the priests.

It is generally accepted amongst historians that the Kulturkampf measures targeted the Catholic Church under Pope Pius IX with discriminatory sanctions. Many historians also point out anti-Polish elements in the policies in other contexts.

In Catholic countries

Anti-clericalism is a historical movement that opposes religious (generally Catholic) institutional power and influence in all aspects of public and political life, and the involvement of religion in the everyday life of the citizen. It suggests a more active and partisan role than mere laïcité. The goal of anti-clericalism is sometimes to reduce religion to a purely private belief-system with no public profile or influence. However, many times it has included outright suppression of all aspects of faith.

Anti-clericalism has at times been violent, leading to murders and the desecration, destruction and seizure of church property. Anti-clericalism in one form or another has existed throughout most of Christian history, and is considered to be one of the major popular forces underlying the 16th century reformation. Some of the philosophers of the Enlightenment, including Voltaire, continually attacked the Catholic Church, both its leadership and priests, claiming that many of its clergy were morally corrupt. These assaults in part led to the suppression of the Jesuits, and played a major part in the wholesale attacks on the very existence of the Church during the French Revolution in the Reign of Terror and the program of dechristianization. Similar attacks on the Church occurred in Mexico and in Spain in the twentieth century.

Brazil

Brazil has the largest number of Catholics in the world, therefore it has not experienced any large anti-Catholicism movements. Even during times in which the Church was experiencing intense conservativeness, such as the Brazilian military dictatorship, anti-Catholicism was not advocated by the left-wing movements (instead, the Liberation theology gained force). However, with the growing number of Protestants (especially Neo-Pentecostals) in the country, anti-Catholicism has gained strength. A pivotal moment of the rising anti-Catholicism was the kicking of the saint episode in 1995. However, owing to the protests of the Catholic majority, the perpetrator was dispatched to Africa.

France

During the French Revolution (1789-95) clergy and religious were persecuted and church property was destroyed and confiscated by the new government as part of a process of Dechristianization, the aim of which was the destruction of Catholic practice and of the very faith itself, culminating the the imposition of the atheistic Cult of Reason and then the deistic Cult of the Supreme Being. Persecution led Catholics in the west of France to engage in a counterrevolution, The War in the Vendee, and when the state was victorious it put down the population in what some call the first modern genocide. The French invasions of Italy (1796-99) included an assault on Rome and the exile of Pope Pius VI in 1798. Relations improved from 1802 until 1809, when Napoleon invaded the Papal States and imprisoned Pope Pius VII. By 1815 the Papacy supported the growing alliance against Napoleon, and was re-instated as the state church during the conservative Bourbon Restoration of 1815-30. The brief French Revolution of 1848 again opposed the Church, but the Second French Empire (1848-71) gave it full support. The history of 1789-1871 had established two camps – liberals against the Church and conservatives supporting it – that largely continued until the Vatican II process in 1962-65.

France's Third Republic (1871-1940) was cemented by anti-clericalism, the desire to secularise the State and social life, faithful to the French Revolution. The Dreyfus affair again polarised opinion in the 1890s. In the Affaire Des Fiches, in France in 1904–1905, it was discovered that the militantly anticlerical War Minister under Emile Combes, General Louis André, was determining promotions based on the French Masonic Grand Orient's huge card index on public officials, detailing which were Catholic and who attended Mass, with the goal of preventing their promotions.

Mexico

Following the Revolution of 1860, US-backed President Benito Juárez, issued a decree nationalizing church property, separating church and state, and suppressing religious orders.

Following the revolution of 1910, the new Mexican Constitution of 1917 contained further anti-clerical provisions. Article 3 called for secular education in the schools and prohibited the Church from engaging in primary education; Article 5 outlawed monastic orders; Article 24 forbade public worship outside the confines of churches; and Article 27 placed restrictions on the right of religious organizations to hold property. Article 130 deprived clergy members of basic political rights.

Mexican President Plutarco Elías Calles's enforcement of previous anti-Catholic legislation denying priests' rights, enacted as the Calles Law, prompted the Mexican Episcopate to suspend all Catholic worship in Mexico from August 1, 1926 and sparked the bloody Cristero War of 1926–1929 in which some 50,000 peasants took up arms against the government. Their slogan was "Viva Cristo Rey!" (long live Christ the King).

The suppression of the Church included the closing of many churches and the killing and forced marriage of priests. The persecution was most severe in Tabasco under the strident atheist governor Tomás Garrido Canabal.

The effects of the war on the Church were profound. Between 1926 and 1934 at least 40 priests were killed. Where there were 4,500 priests serving the people before the rebellion, in 1934 there were only 334 priests licensed by the government to serve fifteen million people, the rest having been eliminated by emigration, expulsion and assassination. It appears that ten states were left without any priests. Other sources, indicate that the persecution was such that by 1935, 17 states were left with no priests at all.

Some of the Catholic casualties of this struggle are known as the Saints of the Cristero War. Events relating to this were famously portrayed in the novel The Power and the Glory by Graham Greene. The persecution of Catholics was most severe in the state of Tabasco under the Governor Tomás Garrido Canabal. Under the rule of Garrido many priests were killed, all Churches in the state were closed and priests who still survived were forced to marry or flee at risk of losing their lives.

Haiti

François and Jean-Claude Duvalier's family dictatorship of Haiti wanted to weaken the control of the Catholic Church so as to ensure loyalty to their regimes. The senior Duvalier was excommunicated by the Vatican for his blatant anti-clericalism, but it was rescinded as part of the negotiations to renew communications with the Vatican. The Catholic Church, particularly in the form of Jean Bertrand Aristide was instrumental in overthrowing the younger Duvalier.

Italy

In 1860 through 1870, the new Italian government closed various monasteries, confiscated their property, expelled religious orders and imprisoned or banished bishops who opposed this.

Spain

Anti-clericalism in Spain at the start of the Spanish Civil War resulted in the killing of almost 7,000 clergy, the destruction of hundreds of churches and the persecution of lay people in Spain's Red Terror. Hundreds of Martyrs of the Spanish Civil War have been beatified and hundreds more were beatified in October 2007.

Colombia

Anti-Catholic and anti-clerical sentiments, some spurred by an anti-clerical conspiracy theory which was circulating in Colombia during the mid-twentieth century led to persecution of Catholics and killings, most specifically of the clergy, during the events known as La Violencia.

Poland

Catholicism in Poland, the religion of the vast majority of the population, was severely persecuted during World War II, following the Nazi invasion of the country and its subsequent annexation into Germany. Over 3 million Catholics of Polish descent were murdered during the Holocaust. Among them was Saint Maximillian Kolbe. In 1999, 108 Polish Catholic victims of the Holocaust, including 3 bishops, 52 priests, 26 monks, 3 seminarians, 8 nuns and 9 lay people, were beatified by Pope John Paul II as the 108 Martyrs of World War Two.

Catholicism continued to be persecuted under the Communist regime from the 1950s. Current Stalinist ideology claimed that the Church and religion in general were about to disintegrate. To begin with, Archbishop Wyszyński entered into an agreement with the Communist authorities, which was signed on 14 February 1950 by the Polish episcopate and the government. The Agreement regulated the matters of the Church in Poland. However, in May of that year, the Sejm breached the Agreement by passing a law for the confiscation of Church property.

On 12 January 1953, Wyszyński was elevated to the rank of cardinal by Pius XII as another wave of persecution began in Poland. When the bishops voiced their opposition to state interference in ecclesiastical appointments, mass trials and the internment of priests began - the cardinal being one of its victims. On 25 September 1953 he was imprisoned at Grudziądz, and later placed under house arrest in monasteries in Prudnik near Opole and in Komańcza in the Bieszczady Mountains. He was not released until 26 October 1956.

Pope John Paul II, who was born in Poland as Karol Wojtyla, often cited the persecution of Polish Catholics in his stance against Communism.

Anti-Catholicism in totalitarian ideologies

Nazi Germany

The Nazi ideology was anti-Christian and particularly anti-Catholic. Catholicism was widely suppressed in Nazi Germany from 1933 on. State measures started with sermons being supervised and grew to the abduction of clerics, as well as laymen, to concentration camps.

Following the 1939 Occupation of Poland, the Roman Catholic Church was even more violently suppressed in Reichsgau Wartheland and the General Government. Churches were closed, with clergy deported, imprisoned, or killed, among them Maximilian Kolbe. Between 1939 and 1945, 2,935 members of the Polish clergy (18%) were killed in concentration camps. In the city of Chełmno, for example, 48% of the Catholic clergy were killed.

Russia and Eastern Europe

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (December 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2010) |

Less widely known in the West has been the anti-Catholicism found in countries where the Eastern or Orthodox Christian Churches have prevailed historically. This form of anti-Catholicism has its roots in the Great Schism between the Western and Eastern Church in 1054, and the Sack of Constantinople by Catholic forces from Western Europe in the Fourth Crusade in 1204.

Israel

The roots of Anti-Catholicism in Israel can be traced back to the origin of the Jewish state in 1948 when several villages with majority Catholic populations, such as Kafr Bir'im and Iqrit, were forcibly depopulated by the Israel Defence Forces. Catholic priests have been expelled from the country ., and dozens of churches have been occupied, closed or forcibly sold since 1948., . More recently Israel has denied residence status to Catholic clerics and has attempted to block the appointment of Catholic bishops. Israeli government attempts such as the failed 1998 effort to block the Holy See's appointment of Boutros Mouallem as archbishop of Galilee were condemned by the Vatican and other nations. Suspicion and hostility towards Catholic clerics has led to incidents such as the October 2002 detention and harassment of Melkite Greek Catholic Archbishop Elias Chacour and Archbishop Boutros Mouallem, who were prevented from leaving Jerusalem to attend an interfaith meeting in London.

Anti-Catholicism in popular culture

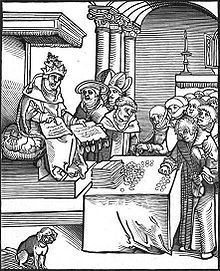

Main article: Anti-Catholicism in literature and mediaAnti-Catholic stereotypes are a long-standing feature of English literature, popular fiction, and even pornography. Gothic fiction is particularly rich in this regard. Lustful priests, cruel abbesses, immured nuns, and sadistic inquisitors appear in such works as The Italian by Ann Radcliffe, The Monk by Matthew Lewis, Melmoth the Wanderer by Charles Maturin and "The Pit and the Pendulum" by Edgar Allan Poe.

See also

References

- anti-catholicism. Dictionary.com. WordNet 3.0. Princeton University. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/anti-catholicism (accessed: November 13, 2008).

- Building Unity, edited by Burgess and Gross, at books.google.com

-

Smalcald Articles, Article four (1537)

- ...the Pope is the very Antichrist, who has exalted himself above, and opposed himself against Christ because he will not permit Christians to be saved without his power, which, nevertheless, is nothing, and is neither ordained nor commanded by God. This is, properly speaking to exalt himself above all that is called God as Paul says, 2 Thess. 2, 4. Even the Turks or the Tartars, great enemies of Christians as they are, do not do this, but they allow whoever wishes to believe in Christ, and take bodily tribute and obedience from Christians... Therefore, just as little as we can worship the devil himself as Lord and God, we can endure his apostle, the Pope, or Antichrist, in his rule as head or lord. For to lie and to kill, and to destroy body and soul eternally, that is wherein his papal government really consists... The Pope, however, prohibits this faith, saying that to be saved a person must obey him. This we are unwilling to do, even though on this account we must die in God's name. This all proceeds from the fact that the Pope has wished to be called the supreme head of the Christian Church by divine right. Accordingly he had to make himself equal and superior to Christ, and had to cause himself to be proclaimed the head and then the lord of the Church, and finally of the whole world, and simply God on earth, until he has dared to issue commands even to the angels in heaven...Smalcald Articles, Article 4

- ...Now, it is manifest that the Roman pontiffs, with their adherents, defend godless doctrines and godless services. And the marks of Antichrist plainly agree with the kingdom of the Pope and his adherents. For Paul, in describing Antichrist to the Thessalonians, calls him 2 Thess. 2, 3: an adversary of Christ, who opposeth and exalteth himself above all that is called God or that is worshiped, so that he as God sitteth in the temple of God. He speaks therefore of one ruling in the Church, not of heathen kings, and he calls this one the adversary of Christ, because he will devise doctrine conflicting with the Gospel, and will assume to himself divine authority...Treatise on the Power and in the Triglot translation of the Book of Concord

- 25.6. There is no other head of the Church but the Lord Jesus Christ: nor can the Pope of Rome in any sense be head thereof; but is that Antichrist, that man of sin and son of perdition, that exalts himself in the Church against Christ, and all that is called God.

- 26.4. The Lord Jesus Christ is the Head of the church, in whom, by the appointment of the Father, all power for the calling, institution, order or government of the church, is invested in a supreme and sovereign manner; neither can the Pope of Rome in any sense be head thereof, but is that antichrist, that man of sin, and son of perdition, that exalteth himself in the church against Christ.

- "The whole succession of Popes from Gregory VII. are undoubtedly antichrist. Yet this hinders not, but that the last Pope in this succession will be more eminently the antichrist, the man of sin, adding to that of his predecessors a peculiar degree of wickedness from the bottomless pit. This individual person, as Pope, is the seventh head of the beast; as the man of sin, he is the eighth, or the beast himself."ee section of the book commentating on the Book of Revelation on the United Methodist Church website, or Explanatory Notes Upon the New Testament

- Edward Gibbon (1994 edition edited by David Womersley) The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Penguin Books: Vol 1, 469

- J.R.H. Moorman (1973) A History of the Church in England. London, A&C Black: 457

- Steven Roud (2006) The English Year. London, Penguin: 455-63

- Lewes Bonfire Council, More Information on Bonfire, Accessed 3 December 2007

- Jenkins, Philip (1 April 2003). The New Anti-Catholicism: The Last Acceptable Prejudice. Oxford University Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-19-515480-0.

- Mannard, Joseph G. (1981). American Anti-Catholicism and its Literature. Archived from the original on 2009-10-25.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "The Coming Catholic Church". By David Gibson. HarperCollins: Published 2004.

- Ellis, John Tracy.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - Annotation

- Letter to Alexander von Humboldt, December 6, 1813

- Letter to Horatio G. Spafford, March 17, 1814

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1972). The Oxford History of the American People. New York City: Mentor. p. 361. ISBN 0-451-62600-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Bilhartz, Terry D. Urban Religion and the Second Great Awakening. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 115. ISBN 0-838-63227-0.

- Jimmy Akin (2001-03-01). "The History of Anti-Catholicism". This Rock. Catholic Answers. Retrieved 2008-11-10.

- Billington, Ray Allen. The Protestant Crusade, 1800-1860: A Study of the Origins of American Nativism. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1938.

- http://www.blaineamendments.org/

- http://www.firstamendmentcenter.org/analysis.aspx?id=11498

- Bush, Jeb (March 4, 2009). NO:Choice forces educators to improve. The Atlanta Constitution-Journal.

- Helmstadter, Richard J., Freedom and religion in the nineteenth century, p. 19, Stanford Univ. Press 1997

- Template:En icon Norman Davies (1982). God's Playground. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-05353-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Template:En icon Adam Zamoyski (1993). The Polish Way: A Thousand-Year History of the Poles and Their Culture. Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-7818-0200-8.

- Template:Pl icon Maciej Milczarczyk (1994). Historia; W imię wolności. Warsaw: WSiP. pp. 196–198. ISBN 83-02-05454-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Template:Pl icon Andrzej Chwalba (2000). Historia Polski 1795-1918. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie. p. 671. ISBN 83-08-03053-X.

- Template:Pl icon Piotr Szlanta (2001). "Admirał Gopła". Mówią wieki. 501 (09/2001).

- Template:En icon "Kulturkampf". New Catholic Dictionary. 1910.

It was the distinguished Liberal politician and scientist, Professor Rudolph Virchow, who first called it the Kulturkampf, or struggle for civilization.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Template:En icon Leonore Koschnick, Agnete von Specht (2001). "The Social Dimension: "Founders" and "Enemies of the Empire"". Bismarck: Prussia, Germany, and Europe. Retrieved 2006-02-16.

- IBGE - Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics). Religion in Brazil - 2000 Census. Accessed 2009-01-06

- Tallet, Frank Religion, Society and Politics in France Since 1789 p. 1-2, 1991 Continuum International Publishing

- Foster, J. R. (1 February 1988). The Third Republic from Its Origins to the Great War, 1871–1914. Cambridge University Press. p. 84. ISBN 0-521-35857-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Larkin, Church and State after the Dreyfus Affair, pp. 138–41: `Freemasonry in France’, Austral Light 6, 1905, pp. 164–72, 241-50.

- ^ Van Hove, Brian Blood-Drenched Altars Faith & Reason 1994

- ^ Scheina, Robert L. Latin America's Wars: The Age of the Caudillo, 1791–1899 p. 33 (2003 Brassey's) ISBN 1-57488-452-2

- Ruiz, Ramón Eduardo Triumphs and Tragedy: A History of the Mexican People p.393 (1993 W. W. Norton & Company) ISBN 0-393-31066-3

- Mark Almond (1996) Revolution: 500 Years of Struggle For Change: 136-7

- Barbara A. Tenenbaum and Georgette M. Dorn (eds.), Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture (New York: Scribner's, 1996).

- Stan Ridgeway, "Monoculture, Monopoly, and the Mexican Revolution" Mexican Studies / Estudios Mexicanos 17.1 (Winter, 2001): 143.

- Ulrich Muller (2009-11-25). "Congregation of the Most Precious Blood". Catholic Enclopedia 1913. Catholic Encyclopedia.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - Michael Ott (2009-11-25). "Pope Pius IX". Catholic Enclopedia 1913. Catholic Encyclopedia.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - de la Cueva, Julio "Religious Persecution, Anticlerical Tradition and Revolution: On Atrocities against the Clergy during the Spanish Civil War" Journal of Contemporary History Vol.33(3) p. 355

- New Evangelization with the Saints, L'Osservatore Romano 28 November 2001, page 3(Weekly English Edition)

- Tucson priests one step away from sainthood Arizona Star 06.12.2007

- Williford, Thomas J. Armando los espiritus: Political Rhetoric in Colombia on the Eve of La Violencia, 1930–1945 p.217-278 (Vanderbilt University 2005)

- ^ John S. Conway, "The Nazi Persecution of the Churches, 1933-1945", Regent College Publishing, 1997

- Weigel, George (2001). Witness to Hope - The Biography of Pope John Paul II. HarperCollins.

- Craughwell, Thomas J., The Gentile Holocaust Catholic Culture, Accessed July 18, 2008

- Khalidi, Walid (1992). "All that Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948.". IPS. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Gruber, Ruth (August 14, 1998). "Israel Opposes Vatican Choice of Palestinian Archbishop". The Jewish News Weekly.

- "Vatican Rebukes Israel Over Comments On Palestinian Bishop ". Catholic World News. August 7, 1998.

- Solheim, James (October 23, 2002). "Christian Leaders from Jerusalem Blocked From Attending Interfaith Meeting in London". Episcopal News Service.

- Patrick R O'Malley (2006) Catholicism, sexual deviance, and Victorian Gothic culture. Cambridge University Press

External material

- Anbinder; Tyler Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s 1992

- Bennett; David H. The Party of Fear: From Nativist Movements to the New Right in American History University of North Carolina Press, 1988

- Billingon, Ray. The Protestant Crusade, 1830–1860 (1938)

- Blanshard; Paul.American Freedom and Catholic Power Beacon Press, 1949

- Thomas M. Brown, "The Image of the Beast: Anti-Papal Rhetoric in Colonial America", in Richard O. Curry and Thomas M. Brown, eds., Conspiracy: The Fear of Subversion in American History (1972), 1-20.

- Steve Bruce, No Pope of Rome: Anti-Catholicism in Modern Scotland (Edinburgh, 1985).

- Elias Chacour: "Blood Brothers. A Palestinian Struggles for Reconciliation in the Middle East" ISBN 0-8007-9321-8 with Hazard, David, and Baker III, James A., Secretary (Foreword by) 2nd Expanded ed. 2003. Archbishop of Galilee, born in Kafr Bir'im, the book covers his childhood growing up in the town. (The first six chapters of Blood Brothers can be downloaded http://web.archive.org/web/)*/http://twelvedaystojerusalem.org/chacour/pdf/BloodBrothers.pdf here (the November 8, 2005 link)].

- Robin Clifton, "Popular Fear of Catholics during the English Revolution", Past and Present, 52 ( 1971), 23-55.

- Cogliano; Francis D. No King, No Popery: Anti-Catholicism in Revolutionary New England Greenwood Press, 1995

- David Brion Davis, "Some Themes of Counter-subversion: An Analysis of Anti-Masonic, Anti-Catholic and Anti-Mormon Literature", Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 47 (1960), 205-224.

- Andrew M. Greeley, An Ugly Little Secret: Anti-Catholicism in North America 1977.

- Henry, David. "Senator John F. Kennedy Encounters the Religious Question: I Am Not the Catholic Candidate for President." Contemporary American Public Discourse. Ed. H. R. Ryan. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, Inc., 1992. 177-193.

- Higham; John. Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860–1925 1955

- Hinckley, Ted C. "American Anti-catholicism During the Mexican War" Pacific Historical Review 1962 31(2): 121-137. ISSN 0030-8684

- Hostetler; Michael J. "Gov. Al Smith Confronts the Catholic Question: The Rhetorical Legacy of the 1928 Campaign" Communication Quarterly. Volume: 46. Issue: 1. 1998. Page Number: 12+.

- Philip Jenkins, The New Anti-Catholicism: The Last Acceptable Prejudice (Oxford University Press, New ed. 2004). ISBN 0-19-517604-9

- Jensen, Richard. The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict, 1888–1896 (1971)

- Jensen, Richard. "'No Irish Need Apply': A Myth of Victimization," Journal of Social History 36.2 (2002) 405-429, with illustrations

- Karl Keating, Catholicism and Fundamentalism — The Attack on "Romanism" by "Bible Christians" (Ignatius Press, 1988). ISBN 0-89870-177-5

- Kenny; Stephen. "Prejudice That Rarely Utters Its Name: A Historiographical and Historical Reflection upon North American Anti-Catholicism." American Review of Canadian Studies. Volume: 32. Issue: 4. 2002. pp: 639+.

- Khalidi, Walid. "All that Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948." 1992. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- McGreevy, John T. "Thinking on One's Own: Catholicism in the American Intellectual Imagination, 1928–1960." The Journal of American History, 84 (1997): 97-131.

- J.R. Miller, "Anti-Catholic Thought in Victorian Canada" in Canadian Historical Review 65, no.4. (December 1985), p. 474+

- Moore; Edmund A. A Catholic Runs for President 1956.

- Moore; Leonard J. Citizen Klansmen: The Ku Klux Klan in Indiana, 1921–1928 University of North Carolina Press, 1991

- E. R. Norman, Anti-Catholicism in Victorian England (1968).

- D. G. Paz, "Popular Anti-Catholicism in England, 1850–1851", Albion 11 (1979), 331-359.

- Thiemann, Ronald F. Religion in Public Life Georgetown University Press, 1996.

- Carol Z. Wiener, "The Beleaguered Isle. A Study of Elizabethan and Early Jacobean Anti-Catholicism", Past and Present, 51 (1971), 27-62.

- Wills, Garry. Under God 1990.

- White, Theodore H. The Making of the President 1960 1961.

| Theology | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||