| Revision as of 20:33, 19 June 2010 edit85.65.99.40 (talk) ce; smaller images← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:36, 19 June 2010 edit undo85.65.99.40 (talk) →BiographyNext edit → | ||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| In many of his prints of domestic scenes, the same woman and child reappear, leading to speculation that they were his wife and child. | |||

| In his youth, he became a pupil of the painter ]. Some say that Utamaro was his son as well. He lived in Sekien's house while he growing up and the relationship between the two artists continued until Sekien's death in 1788. Sekien originally was trained in the aristocratic ] of painting, but in middle age he started to lean toward the popular ], a ] of ]. Sekien is known to have had a number of other pupils, who failed to achieve distinction. | |||

| At the approximate age of twenty-two, his earliest known major professional artistic work was created, a cover for a ] playbook in 1775 that was published under a ], the ] of ''Toyoaki''. He then produced a number of actor and warrior prints, along with theatre programmes, and other such materials. From the spring of 1781, he switched his ''gō'' to ''Utamaro'', and began painting and designing woodblock prints of women, but these early works are not considered of important value. | At the approximate age of twenty-two, his earliest known major professional artistic work was created, a cover for a ] playbook in 1775 that was published under a ], the ] of ''Toyoaki''. He then produced a number of actor and warrior prints, along with theatre programmes, and other such materials. From the spring of 1781, he switched his ''gō'' to ''Utamaro'', and began painting and designing woodblock prints of women, but these early works are not considered of important value. | ||

Revision as of 20:36, 19 June 2010

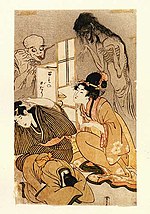

Kitagawa Utamaro (喜多川 歌麿, ca. 1753 - October 31, 1806) was a Japanese printmaker and painter, who is considered one of the greatest artists of woodblock prints (ukiyo-e). His name was romanized archaically as Outamaro. He is known especially for his masterfully composed studies of women, known as bijinga. He also produced nature studies, particularly illustrated books of insects.

His work reached Europe in the mid-nineteenth century, where it was very popular, enjoying particular acclaim in France. He influenced the European Impressionists, particularly with his use of partial views and his emphasis on light and shade. The reference to the "Japanese influence" among these artists often refers to the work of Utamaro.

Biography

Kitagawa Ichitarō (later Utamaro) was born either in Edo (present-day Tokyo), Kyoto, or Osaka, or in a provincial town, in 1753. Another long-standing tradition asserts that he was born in Yoshiwara, the courtesan district of Edo, being the son of a tea-house owner, but there is no evidence of this. Following the Japanese custom of the time, he changed his name as he became mature, and also took the name, Ichitarō Yusuke, as he became older.

In many of his prints of domestic scenes, the same woman and child reappear, leading to speculation that they were his wife and child.

In his youth, he became a pupil of the painter Toriyama Sekien. Some say that Utamaro was his son as well. He lived in Sekien's house while he growing up and the relationship between the two artists continued until Sekien's death in 1788. Sekien originally was trained in the aristocratic Kanō School of painting, but in middle age he started to lean toward the popular Ukiyo-e, a genre of Japanese woodblock prints. Sekien is known to have had a number of other pupils, who failed to achieve distinction.

At the approximate age of twenty-two, his earliest known major professional artistic work was created, a cover for a Kabuki playbook in 1775 that was published under a pseudonym, the gō of Toyoaki. He then produced a number of actor and warrior prints, along with theatre programmes, and other such materials. From the spring of 1781, he switched his gō to Utamaro, and began painting and designing woodblock prints of women, but these early works are not considered of important value.

At some point in the mid-1780s, probably 1783, he went to live with the young and rising publisher, Tsutaya Jūzaburō. It is estimated that he lived there for approximately five years. He seems to have become a principal artist for the Tsutaya firm. Evidence of his prints for the next few years is sporadic, as he mostly produced illustrations for books of kyoka, literally 'crazy verse', a parody of the classical waka form. None of his work produced during the period 1790-1792 has survived.

In about 1791 Utamaro gave up designing prints for books and concentrated on making single portraits of women displayed in half-length, rather than the prints of women in groups favoured by other ukiyo-e artists. In 1793 he achieved recognition as an artist, and his semi-exclusive arrangement with the publisher Tsutaya Jūzaburō was terminated. He then went on to produce several very famous series of works, all featuring women of the Yoshiwara district.

Over the years, he also occupied himself with a number of volumes of animal, insect, and nature studies and shunga, or erotica. Shunga prints were quite acceptable in Japanese culture, not associated with a negative concept of pornography as found in western cultures, but considered rather as a natural aspect of human behavior, and circulated among all levels of Japanese society.

In 1797, Tsutaya Jūzaburō died and apparently, Utamaro was very upset by the loss of his long-time friend and supporter. Some commentators feel that after this event, his work never reached the heights it had previously.

In 1804, at the height of his success, he ran into legal trouble by publishing prints related to a banned historical novel. The prints, entitled Hideyoshi and his Five Concubines, depicted the wife and concubines of the military ruler, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who lived from 1536 to 1598. Consequently, Utamaro was accused of insulting the real Hideyoshi's dignity. He was sentenced to be handcuffed for fifty days (some accounts say he briefly was imprisoned). According to some sources, the experience crushed him emotionally and ended his career as an artist.

He died two years later, on the twentieth day of the ninth month of 1806 (the lunar calendar date format for October 31), aged about fifty-three, in Edo.

Pupils

After Utamaro's death, his pupil, Koikawa Shunchō, continued to produce prints in the style of his mentor and took over the gō, Utamaro, until 1820. These prints, produced during that fourteen-year-period as if Utamaro was the artist, now are referred to as the work of Utamaro II. After 1820 Koikawa Shunchō changed his gō to Kitagawa Tetsugorō, producing his subsequent work under that name.

Retrospective observations

Utamaro produced over two thousand prints during his working career, along with a number of paintings, surimono, as well as many illustrated books, including over thirty shunga books, albums, and related publications. Among his best known works are the series Ten Studies in Female Physiognomy; A Collection of Reigning Beauties; Great Love Themes of Classical Poetry (sometimes called Women in Love containing individual prints such as Revealed Love and Pensive Love); and Twelve Hours in the Pleasure Quarters.

He alone, of his contemporary ukiyo-e artists, achieved a national reputation during his lifetime. His sensuous female beauties generally are considered the finest and most evocative bijinga in all of ukiyo-e. He succeeded in capturing subtle aspects of personality and transient moods of women of all classes, ages, and circumstances. His reputation has remained undiminished since; his work is known worldwide, and he is generally regarded as one of the half-dozen greatest ukiyo-e artists of all time.

Print series

A partial list of his print series and their dates includes

- Chosen Poems (1791-1792)

- Ten Types of Women's Physiognomies (1792-1793)

- Famous Beauties of Edo (1792-1793)

- Ten Learned Studies of Women (1792-1793)

- Anthology of Poems: The Love Section (1793-1794)

- Snow, Moon, and Flowers of the Green Houses (1793-1795)

- Array of Supreme Beauties of the Present Day (1794)

- Twelve Hours of the Green Houses (1794-1795)

- Flourishing Beauties of the Present Day (1795-1797)

- An Array of Passionate Lovers (1797-1798)

- Ten Forms of Feminine Physiognomy (1802)

References

- Jack Hillier, Utamaro: Color Prints and Paintings (Phaidon, London, 1961)

- Tadashi Kobayashi, (translated Mark A. Harbison), Great Japanese Art: Utamaro (Kodansha, Tokyo, 1982)

- Muneshige Narazaki, Sadao Kikuchi, (translated John Bester), Masterworks of Ukiyo-E: Utamaro (Kodansha, Tokyo, 1968)

- Shugo Asano, Timothy Clark, The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro (British Museum Press, London, 1995)

- Julie Nelson Davis, "Utamaro and the Spectacle of Beauty" (Reaktion Books, London, and University of Hawai'i Press, 2007)

- Gina Collia-Suzuki, "Utamaro Revealed" (Nezu Press, 2008)

- Gina Collia-Suzuki, "The Complete Woodblock Prints of Kitagawa Utamaro: A Descriptive Catalogue" (Nezu Press, 2009) - complete catalogue raisonné

External links

- Kitagawa Utamaro Online

- Utamaro

- (from "Collection of Insects in Pictures")

- Kitagawa Utamaro at Hill-Stead Museum, Farmington, Connecticut

- A selection of prints by Kitagawa Utamaro

- Exploring the World of Kitagawa Utamaro

- Utamaro prints in the Minneapolis Institute of Arts

- Utamaro's books in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge