| Revision as of 18:46, 30 July 2010 editTeeninvestor (talk | contribs)Pending changes reviewers8,552 edits Adding in this mid-1980's discovery.← Previous edit | Revision as of 18:47, 30 July 2010 edit undoPericlesofAthens (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers76,810 editsm →FlamethrowerNext edit → | ||

| Line 183: | Line 183: | ||

| ====Flamethrower==== | ====Flamethrower==== | ||

| ] flamethrower from the '']'' manuscript of 1044 CE, ].]] | ] flamethrower from the '']'' manuscript of 1044 CE, ].]] | ||

| Although the Byzantines had been using a single-piston proto-flame thrower as early as the 7th century<ref>Joseph Needham: „Science and Civilisation in China“,Cambridge University Press, 1974, Vol. 7, ISBN 0521303583, p.84</ref>, the first true flamethrower capable of emitting a continuous stream of fire was introduced in China around 900 CE.<ref>{{harvnb|Temple|1986|p=229}}</ref> Flamethrowers were employed in naval combat in the ], and large-scale use of the |

Although the Byzantines had been using a single-piston proto-flame thrower as early as the 7th century<ref>Joseph Needham: „Science and Civilisation in China“,Cambridge University Press, 1974, Vol. 7, ISBN 0521303583, p.84</ref>, the first true flamethrower capable of emitting a continuous stream of fire was introduced in China around 900 CE.<ref>{{harvnb|Temple|1986|p=229}}</ref> Flamethrowers were employed in naval combat in the ], and large-scale use of the flamethrower is recorded in 975, when the Southern Tang navy employed flamethrowers against Song naval forces, but the wind blew the other way, causing the Southern Tang fleet to be immolated, and allowing the Song to conquer South China.<ref>{{harvnb|Temple|1986|p=230}}</ref> During Song times, the flamethrower was used not only in naval combat but also in defense of cities, where they were placed on the city walls to incinerate any attacking soldiers.<ref>{{harvnb|Temple|1986|p=231}}</ref> | ||

| ====Rockets==== | ====Rockets==== | ||

Revision as of 18:47, 30 July 2010

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Chinese Armies (Pre-1911) | |

|---|---|

| Leaders | Chinese Emperor |

| Dates of operation | 2200 BCE - 1911 CE |

| Active regions | China, Southeast Asia, Central Asia, and Mongolia |

| Part of | Chinese Empire |

| Opponents | Donghu, Xirong, Vietnam, Xiongnu, Xianbei, Qiang, Jie, Di, Korea, Khitan, Gokturks, Tibetans, Jurchens, Mongols, Japan, and others. |

| Battles and wars | wars involving China |

| Part of a series on the | ||||||||||||||||

| History of China | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Prehistoric

|

||||||||||||||||

Ancient

|

||||||||||||||||

Imperial

|

||||||||||||||||

Modern

|

||||||||||||||||

| Related articles | ||||||||||||||||

Ever since Chinese civilization was founded, organized military forces have existed throughout China. The recorded military history of China extends from about 2200 BCE to the present day. Although traditional Chinese Confucian philosophy favoured peaceful political solutions and showed contempt for brute military force, the military was influential in most Chinese states. The Chinese pioneered the use of crossbows, advanced metallurgical standardization for arms and armor, early gunpowder weapons, and other advanced weapons, but also adopted nomadic cavalry and Western military technology. In addition, China's armies also benefited from an advanced logistics system as well as a rich strategic tradition, beginning with Sun Tzu's "The Art of war", that deeply influenced military thought.

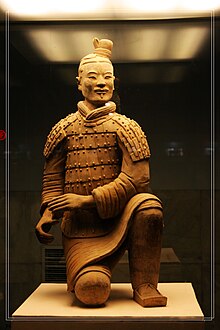

Early Chinese armies, such as that of the Shang and Zhou, were based on chariots and bronze weapons, much like their contemporaries in western Asia and Egypt. These small armies were ill-trained, poorly equipped, and had poor endurance However, by the Warring States Period, the introduction of iron weapons, crossbows, and cavalry revolutionized Chinese warfare. Professional standing armies replaced the unreliable peasant levies of old, and professional generals replaced aristocrats at the head of the army. This occurred concurrently with the establishment of a centralized state that was to become the norm for China. Under the Qin and Han Dynasties, China was unified and its troops conquered territories in all directions, and established China's frontiers that would last to the present day. These victories ushered in a golden age for China.

Despite occasional defeats, particularly by the nomads on the northern frontier, China maintained a strong and powerful army throughout most of the imperial Era. Although the army became gradually feudal after the fall of the Han Dynasty, a trend that was accelerated during the Wu Hu invasions of the fourth century CE and the Southern and Northern Dynasties period afterwards, a professional army was restored by the Sui Dynasty and Tang Dynasty, bringing a new golden age. Military technology also did not stand still; new equipment and concepts such as gunpowder weaponry and powerful new naval ships were continuously introduced, in order to augment the fighting power of China's military forces.

Despite this, China's military supremacy gradually eroded after the establishment of the Song Dynasty, who was distrustful of the military establishment. Under the Song, China's armies suffered disastrous reverses and China was conquered by the Mongols under Kublai Khan. Although the Ming Dynasty restored Chinese power and a new golden age, China's supremacy was ended by a second foreign conquest, that of the Manchu Qing Dynasty in 1683. They put a stop to improvements in military technology in order to maintain their rule. The Qing Dynasty suffered disastrous defeats to European powers throughout the 19th century that eroded China's sovereignty and lead to the disintegration of the Chinese Empire.

Early Chinese armies were composed of infantry and charioteers, but later imperial Chinese armies had a variety of different troops. These armies were composed of crossbowmen, cavalry, and infantry, who were armed with a wide array amount of equipment. After the Song Dynasty, Chinese armies were also equipped with gunpowder weapons such as fire lances, gunpowder bombs, muskets and cannons. These armies were usually composed mostly of ethnic Chinese, though the Chinese army also employed many subject peoples in their forces, such as Gokturks, Koreans, and Mongols. The Yuan and Qing dynasties, under whom China were ruled by ethnic minorities such as the Mongols and Manchus, employed large numbers of Inner Asian cavalry troops mostly from their own ethnic group, while the infantry are composed of mostly ethnic Han soldiers.

History of military organization

The military history of China stretches from roughly 2200 BCE to the present day. Chinese armies were advanced and powerful, especially after the Warring States Period. These armies were tasked with the twofold goal of defending China and her subject peoples from foreign intruders, and with expanding China's territory and influence across Asia

Pre-Warring States (2100 BCE-479 BCE)

Early Chinese armies were relatively small affairs. Composed of peasant levies, usually dependent serfs upon the king or the feudal lord, these armies were relatively ill equipped. While organized military forces had existed along with the state, little records remain of these early armies. These armies were centered around the chariot-riding nobility, who played a role akin to the European Knight as they were the main fighting force of the army. Bronze weapons such as spears and swords were the main equipment of the both the infantry and charioteers. These armies were ill-trained and haphazardly supplied, meaning that they could not campaign for more than a few months and often had to give up their gains due to lack of supplies.

Nevertheless, under the Shang and Zhou, these armies were able to expand China's territory and influence from a narrow part of the Yellow river valley to all of the North China plain. Equipped with bronze weapons, bows, and armor, these armies won victories against the sedentary Donghu to the East and South, which were the main direction of expansion, as well as defending the western border against the nomadic incursions of the Xirong. However, after the collapse of the Zhou Dynasty in 771 BCE after the Xirong captured its capital Gaojing, China collapsed into a plethora of small states, who warred frequently with each other. The competition between these states would eventually produce the professional armies that marked the Imperial Era of China.

In 1978 a Chinese double edged steel sword dating back 2500 years was found in Changsha. The sword was made during the Spring and Autumn period.

Warring states (479 BCE-221 BCE)

By the time of the Warring states, China had been consolidated into a series of large states. Centralized reforms began that abolished feudalism and created powerful, centralized states. In addition, the power of the aristocracy was curbed and for the first time, professional generals were appointed on merit, rather than birth. Technological advances such as iron weapons and crossbows put the chariot-riding nobility out of business and favored large, professional standing armies, who were well-supplied and could fight a sustained campaign. The size of armies increased; while before 500 BCE Chinese field armies did not exceed 100,000 men, the Battle of Changping in 260 BCE reputedly involved some 1,000,000 men from the two states involved. While this is certainly somewhat exaggerated, it served to show the increased size of armies in this era. The new military system was a centralized system that consisted of large armies commanded by professional generals, who had to report to a king.

In addition to these improvements, the Warring states also saw the introduction of a new arm of the army, cavalry. The first recorded use of cavalry took place in the Battle of Maling, in which general Pang Juan of Wei led his division of 5,000 cavalry into a trap by Qi forces. In 307 BC, King Wuling of Zhao ordered the adoption of nomadic clothing in order to train his own division of cavalry archers.

Qin-Han (221 BCE-184 CE)

In 221 BCE, the Qin unified China and ushered in the Imperial Era of Chinese history. Although it only lasted 15 years, Qin established institutions that would last for millennia. For the rest of Chinese history, a centralized empire was the norm.

During the Qin Dynasty and its successor, the Han, the Chinese armies were faced with a new military threat, that of nomadic confederations such as the Xiongnu in the North. These nomads were fast horse archers who had a significant mobility advantage over the settled nations to the South. In order to counter this threat, the Chinese built the Great Wall as a barrier to these nomadic incursions, and also used diplomacy and bribes to preserve peace. However, in the South, China's territory was roughly doubled as the Chinese conquered much of what is now Southern China, and extended the frontier from the Yangtze to Vietnam.

Armies during the Qin and Han dynasties largely inherited their institutions from the earlier Warring States Period, with the major exception that cavalry forces were becoming more and more important, due to the threat of the Xiongnu. Under Emperor Wu of Han, the Chinese launched a series of massive cavalry expeditions against the Xiongnu, defeating them and conquering much of what is now Northern China, Western China, Mongolia, Central Asia, and Korea. After these victories, Chinese armies were tasked with the goal of holding the new territories against incursions and revolts by peoples such as the Qiang, Xianbei and Xiongnu who had come under Chinese rule. Advances such as the stirrup helped make cavalry forces more effective. The Han also standardized and mass produced iron armor in the form of lamellar or coat of plates. The Eastern Han thoroughly developed heavily armored cavalry and lancers - while cavalry would eventually develop into the super-heavy cataphracts later on.

The structure of the army also changed in this period. While the Qin had utilized a conscript army, by Eastern Han, the army was made up largely of volunteers and conscription could be avoided by paying a fee. Those who presented the government with supplies, horses, or slaves were also exempted from conscription.

Wei-Jin (184 CE-304 CE)

The end of the Han Dynasty saw a massive agrarian uprising that had to be quelled by local governors, who seized the opportunity to form their own armies. The central army disintegrated and was replaced by a series of local warlords, who fought for power until most of the North was unified by Cao Cao, who later formed the Wei Dynasty, which ruled most of China. However, much of Southern China was ruled by two rival Kingdoms, Shu Han and Wu. As a result, this era is known as the Three Kingdoms.

Under the Wei Dynasty, the military system changed from the centralized military system of the Han. Unlike the Han, whose forces were concentrated into a central army of volunteer soldiers, Wei's forces depended on the Buqu, a group for whom soldiering was a hereditary profession. In effect, these armies were hereditary; when a soldier or commander died, a male relative would inherit the position. In addition, provincial armies, which were very weak under the Han, became the bulk of the army under the Wei, for whom the central army was held mainly as a reserve. This military system was also adopted by the Jin Dynasty, who succeeded the Wei and unified China

Era of division (304 CE-589 CE)

In 304 CE, a major event shook China. The Jin Dynasty, who had unified China 24 years earlier, was tottering in collapse due to a major civil war. Seizing this opportunity, barbarian chieftain Liu Yuan and his forces rose against the Chinese. He was followed by many other barbarian leaders, and these rebels were called the "Wu Hu" or literally "Five barbarian tribes". By 316 CE, the Jin had lost all territory north of the Huai river. From this point on, much of North China was ruled by Sinocized barbarian tribes such as the Xianbei, while south China remained under Chinese rule, a period known as the Era of Division. During this era, the military forces of both Northern and southern regimes diverged and developed very differently.

Northern

Northern China was devastated by the Wu Hu uprisings. After the initial uprising, the various tribes fought among themselves in a chaotic era known as the Sixteen Kingdoms. Although brief unifications of the North, such as Later Zhao and Former Qin, occurred, these were relatively short-lived. During this era, the Northern armies, were mainly based around nomadic cavalry, but also employed Chinese as foot soldiers and siege personnel. This military system was rather improvising and ineffective, and the states established by the Wu Hu were mostly destroyed by the Jin Dynasty or the Xianbei.

A new military system did not come until the invasions of the Xianbei in the 5th century CE, by which time most of the Wu Hu had been destroyed and much of North China had been reconquered by the Chinese dynasties in the South. Nevertheless, the Xianbei won many successes against the Chinese, conquering all of North China by 468 CE. The Xianbei state of Northern Wei created the earliest forms of the equal field (均田) land system and the Fubing system (府兵) military system, both of which became major institutions under Sui and Tang. Under the fubing system each headquarters (府) commanded about one thousand farmer-soldiers who could be mobilized for war. In peacetime they were self-sustaining on their land allotments, and were obliged to do tours of active duty in the capital.

Southern

Southern Chinese dynasties, being descended from the Han and Jin, prided themselves on being the successors of the Chinese civilization and disdained the Northern dynasties, who they viewed as barbarian usurpers. Southern armies continued the military system of Buqu or hereditary soldiers from the Jin Dynasty. However, the growing power of aristocratic landowners, who also provided many of the buqu, meant that the Southern dynasties were very unstable; after the fall of the Jin, four dynasties ruled in just two centuries.

This is not to say that the Southern armies did not work well. Southern armies won great victories in the late 4th century CE, such as the battle of Fei at which an 80,000-man Jin army crushed the 300,000-man army of Former Qin, an empire founded by one of the Wu Hu tribes that had briefly unified North China. In addition, under the brilliant general Liu Yu, Chinese armies briefly reconquered much of North China.

Sui-Tang (589 CE- 907 CE)

In 581 CE, the Chinese Yang Jian forced the Xianbei ruler to abdicate, founding the Sui Dynasty and restoring Chinese rule in the North. By 589 CE, he had unified much of China .

The Sui's unification of China sparked a new golden age. During the Sui and Tang, Chinese armies, based on the Fubing system invented during the era of division, won military successes that restored the empire of the Han Dynasty and reasserted Chinese power. The Tang created large contingents of powerful heavy infantry. A key component of the success of Sui and Tang armies, just like the earlier Qin and Han armies, was the adoption of large elements of cavalry. These powerful horsemen, combined with the superior firepower of the Chinese infantry (powerful missile weapons such as recurve crossbows), made Chinese armies powerful.

However, during the Tang Dynasty the Fubing (府兵)system began to break down. Based on state ownership of the land in the Juntian (均田)system, the prosperity of the Tang Dynasty meant that the state's lands were being bought up in ever increasing quantities. Consequently, the state could no longer provide land to the farmers, and the Juntian system broke down. By the 8th century, the Tang had reverted to the centralized military system of the Han. However, this also did not last and it broke down during the disorder of the Anshi Rebellion, which saw many Fanzhen (藩鎮)or local generals become extraordinarily powerful. These Fanzhen were so powerful they collected taxes, raised armies, and made their positions hereditary. Because of this, the central army of the Tang was greatly weakened. Eventually, the Tang Dynasty collapsed and the various Fanzhen were made into separate kingdoms, a situation that would last until the Song Dynasty.

During the Tang, professional military writing and schools began to be set up to train officers, an institution that would be expanded during the Song.

Song (960 CE-1279 CE)

During the Song Dynasty, the emperors were focused on curbing the power of the Fanzhen, local generals who they viewed as responsible for the collapse of the Tang Dynasty. Local power was curbed and most power was centralized in the government, along with the army. In addition, the Song adopted a system in which commands by generals were ad hoc and temporary; this was to prevent the troops from becoming attached to their generals, who could potentially rebel. Successful generals such as Yue Fei (岳飛)and Liu Zen were persecuted by the Song Court who feared they would rebel.

Although the system worked at quelling rebellions, it was a failure in defending China and asserting its power. The Song had to rely on new gunpowder weapons introduced during the late Tang and bribes to fend off attacks by its enemies, such as the Khitan, Tanguts, Jurchens, and Mongols, as well as an expanded army of over 1 million men. In addition, the Song was greatly disadvantaged by the fact their enemies had taken advantage of the era of chaos following the collapse of the Tang to conquer the Great Wall region, allowing them to advance into Northern China unimpeded. Not only that, but the Song also lost the horse-producing regions which made their cavalry extremely inferior. Eventually the Song fell to the Mongol invasions in the 13th century.

The military technology of the Song was very advanced. Gunpowder weapons such as fire lances, cast-iron gunpowder bombs, and hand cannons were employed in large numbers by the Song army.This advanced technology was key for the Song army to fend off its barbarian opponents, such as the Khitans, Jur'chens and Mongols.

Yuan (1279 CE-1368 CE)

Founded by the Mongols who conquered Song China, the Yuan had the same military system as most nomadic peoples to China's north, focused mainly on nomadic cavalry, who were organized based on households and who were led by leaders appointed by the khan.

The Mongol invasion started in earnest only when they acquired their first navy, mainly from Chinese Song defectors. Liu Cheng, a Chinese Song commander who defected to the Mongols, suggested a switch in tactics, and assisted the Mongols in building their own fleet. Many Chinese served in the Mongol navy and army and assisted them in their conquest of Song.

However, in the conquest of China, the Yuan also adopted gunpowder weapons and thousands of Chinese infantry and naval forces into the Mongol army, as well as non-Chinese weapons such as the Muslim counterweight trebuchets. . The Mongol military system began to collapse after the 14th century and by 1368 the Mongols was driven out by the Chinese Ming Dynasty.

Ming (1368 CE-1662 CE)

The Ming focused on building up a powerful standing army that could drive off attacks by foreign barbarians. Beginning in the 14th century, the Ming armies drove out the Mongols and expanded China's territories to include Yunnan, Mongolia, Tibet, much of Xinjiang and Vietnam. The Ming also engaged in Overseas expeditions which included one violent conflict in Sri Lanka. Ming armies incorporated gunpowder weapons into their military force, speeding up a development that had been prevalent since the Song. It is speculated that had the Manchu conquest of China not happened, the Ming army could have become completely equipped with gunpowder weapons, similar to 18th century Europe.

Ming military institutions were largely responsible for the success of Ming's armies. The early Ming's military was organized by the Wei-suo system, which split the army up into numerous "Wei" or commands throughout the Ming frontiers. Each wei was to be self-sufficient in agriculture, with the troops stationed there farming as well as training. This system also forced soldiers to serve hereditarily in the army; although effective in initially taking control of the empire, this military system proved unviable in the long run and collapsed in the 1430s, with Ming reverted to a profesional volunteer army similar to Tang, Song and Later Han.

Throughout most of the Ming's history, the Ming armies were successful in defeating foreign powers such as the Mongols and Japanese and expanding China's influence. However, with the little Ice Age in the 17th century, the Ming Dynasty was faced with a disastrous famine and its military forces disintegrated as a result of the famines spurring from this event.

In 1662, Chinese and European arms clashed when a Ming-loyalist army led by Koxinga starved a Dutch East India Company fort on Taiwan in a seven month long siege into surrender. The final blow to the Company's defense came when a Dutch defector, who would save Koxinga's life in the assault, had pointed the inactive besieging army to the weak points of the Dutch star-shaped fort. While the mainstay of the Chinese forces were archers, the Chinese used cannons too during the siege,, which however the European eye-witnesses did not judge as effective as the Dutch batteries.

Earlier battles between Ming and European vessels took place in the sixteenth century. The Ming Dynasty Imperial Navy defeated a Portuguese fleet led by Martim Affonso in 1522 at the Battle of Tamao. The Chinese destroyed one vessel by targeting its gunpowder magazine, and captured another Portuguese ship.

Qing (1662 CE-1911 CE)

The Qing were another conquest dynasty, similar to the Yuan. The Qing military system depended on the "bannermen" who were Manchus that soldiered as a profession. However, the Qing also incorporated Chinese units into their army, known as the "green armies", and large number of Han Chinese and Koreans of Liao Dong(遼東) were enslaved and enlisted into Three Banner Army (booi ilan gusa), which were under direct command of the Manchu Emperor. Unlike the Song and Ming, however, the Qing armies had a strange neglect for firearms, and did not develop them in any significant way. In addition, the Qing armies also contained a much higher proportion of cavalry than Chinese dynasties, due to the fact the Jurchens were nomads before their rise to rule all of China.

The Qing dynasty engaged a western power for the second time in Chinese history, during the Russian–Manchu border conflicts, again defeating them in battle.

The Qing won many military successes in the Northwest, and were successful in reincorporating much of Mongolia and Xinjiang into China after the fall of the Ming Dynasty, as well as strengthening control over Tibet. However, when faced with western armies in the 19th century, the Qing's military system began to collapse. The only one battle that Qing won with heavier casualties inflicted on the Western side during this era was the Battle of Taku Forts (1859), in which the Chinese used gunpowder weapons like Cannons and muskets to destroy three Anglo French ships and inflict heavy casualties. To compensate for this, a series of "new armies" based on European standards, were formed by the Qing. These armies were mainly composed of Han Chinese, and under Han Chinese commanders such as Zeng Guofan, Zuo Zongtang, Li Hongzhang and Yuan Shikai and thus weakened the Manchus' hold on military power. The Qing also absorbed bandit armies and Generals who defected to the Qing side during rebellions, like the Muslim Generals Ma Zhan'ao, Ma Qianling, Ma Haiyan, and Ma Julung. There were also armies composed of Chinese Muslims led by Muslim Generals like Dong Fuxiang, Ma Anliang, Ma fuxiang, and Ma Fuxing who commanded the Kansu Braves. In 1911 CE, the Chinese revolution overthrew the Manchu Qing Dynasty, and Yuan Shikai forced the Manchu monarch to resign peacefully on the promise that not a single Manchu royal be executed by revolutionaries, and thus began the modern era of Chinese history.

Military philosophy

Chinese military thought's most famous tome is Sun Tzu's Art of war, written in the Warring States Era. In the book, Sun Tzu laid out several important cornerstones of military thought, such as:

- The importance of intelligence.

- The importance of manoeuvring so your enemy is hit in his weakened spot.s

- The importance of morale.

- How to conduct diplomacy so that you gain more allies and the enemy lose allies.

- Having the moral advantage.

- The importance of national unity.

- All warfare is based on deception.

- The importance of logistics.

- The proper relationship between the ruler and the general. Sun Tzu holds the ruler should not interfere in military affairs.

- Difference between Strategic and Tactical strategy.

- No country has benefited from a prolonged war.

- Subduing an enemy without using force is best.

Sun Tzu's work became the cornerstone of military thought, which grew rapidly. By the Han Dynasty, no less than 11 schools of military thought were recognized. During the Song Dynasty, a military academy was established.

Equipment and technology

In their various campaigns, the Chinese armies through the ages, employed a variety of equipment in the different arms of the army. For a large part of its history, Chinese armies had access to some of the most advanced military technology of its day, which helped the Chinese win victories over their opponents. The most notable weaponry used by the Chinese consisted of crossbows, rockets, gunpowder weapons, and other "exotic weapons", but the Chinese also made many advances on conventional iron weapons such as swords and spears that were far superior to other contemporary weapons. Chinese armies also enjoyed extensive logistic support thanks to innovations such as the wheelbarrow and the an efficient horse harness which allowed large armies to be supplied in the field, as well as a complex "military-industrial complex" supported by the state that mass-produced standardized weapons in enormous quantities.

Crossbow

The crossbow, invented by Chinese in the 4th century BCE, was considered the most important weapon of the Chinese armies. The mass use of crossbows allowed Chinese armies to deploy huge amounts of firepower, due to the crossbow's deadly penetration, long range, and rapid rate of fire. As early as the 4th century BCE, Chinese texts describe armies employing up to 10,000 crossbowmen in combat, where their impact was decisive. During the Han Dynasty, it was claimed that up to several hundred thousand crossbows were manufactured for the imperial armies.

Crossbow manufacture was very complex, due to the nature of the firing bolt. Historian Homer Dubs claim that the crossbow firing mechanism "was almost as complex as a rifle bolt, and could only be reproduced by very competent mechanics. This gave an additional advantage, as this made the crossbow "capture-proof" as even if China's barbarian enemies captured them they would not be able to reproduce the weapon. Crossbow ammunition could also only be used in crossbows, and was useless for use in the conventional bows employed China's nomadic enemies.

The Song Dynasty's official military texts described the crossbow thus:

The crossbow is the strongest weapon of China and what the four kinds of barbarians most fear and obey... The crossbow is the most efficient weapon of any, even at distances as small as five feet. The crossbowmen are mustered in separate companies, and when they shoot, nothing can stand in front of them, no enemy formation can keep its order. If attacked by cavalry, the crossbowmen will be as solid as a mountain., shooting off such valleys that nothing will remain alive before them.

The use of the crossbow is also described.

Regarding the use of the crossbow, it cannot be mixed up with hand-to-hand weapons, and it is most beneficial when shot from high ground facing downwards. It only needs to be used so that the men within the formation are loading while the men in the front line of the formation are shooting....then as soon as they have shot their bolts they return again into the formation. Thus the sound of the crossbows is incessant and the enemy can hardly even flee.

In combat, crossbows were often fitted with grid sights to help aim, and several different sizes were used. During the Song Dynasty, huge artillery crossbows were used that could shoot several bolts at once, killing ten men at a time. Even cavalrymen were sometimes issued with crossbows. It was recorded that the crossbow could "penetrate a large elm from a distance of one hundred and forty paces". The range of large artillery crossbows was estimated at 1160 yards, while the range of handheld and cavalry crossbows is estimated at 500 yards and 330 yards respectively. Repeating crossbows were introduced in the eleventh century, which had a very high rate of fire; 100 men could discharge 2000 bolts in 15 seconds, with a range of 200 yards. This weapon became the standard crossbow used during the Song, Ming, and Qing dynasties. Another innovation was the use of poisonous ammunition, which killed any soldier that it touched, even if he was simply scraped or touched by the bolt.

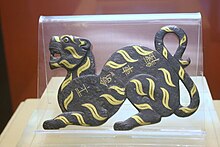

Gunpowder weapons

As inventors of gunpowder, the Chinese were the first to deploy gunpowder weapons in the world. A huge variety of gunpowder weapons were produced, including guns, cannons, mines, the flamethrower, bombs, and rockets. After the rise of the Qing Dynasty, China began to lose its lead in gunpowder weapons to the west, partially because of the Manchus' policies of suppressing gunpowder technology. However, many authors assume that European powers had assumed the global lead in gunpowder warfare by the time of the Western Military Revolution (16th century).

Guns and cannons

Gunpowder was discovered during the late Tang Dynasty by alchemists seeking immortality. The first "proto-gun", the fire lance, was introduced in 905 CE. This consisted of a bamboo or metal tube attached to a spear filled with gunpowder that could be ignited at will, with a range of five metres. It was capable of killing or maiming several soldiers at a time and was mass produced and used especially in the defense of cities. Later versions of the fire lance dropped the spear point and had more gunpowder content. Defenders would often use these single-shot weapons by the thousands, dropping them one after another after they were exhausted. Huge batteries of fire-lances that could fire simulteanously were also invented.

The first true guns and cannons is thought to have been introduced during the 13th century by the Song Dynasty, though historians have discovered a depiction of an early cannon dated in 1128. These cast-iron hand cannons and erupters were mostly fitted to ships and fortifications for defense. After the Mongol conquest, gunpowder spread to the west due to the Mongols' tendency to employ foreigners in government rather than the Chinese, who they feared would rebel. By the Ming Dynasty, huge cannons were being made; Ming military texts mention cannons weighing up to 630 kilograms being cast in the middle of the fifteenth century. Hand-held guns were also produced and used in large quantities, and Ming artisans made attempts to develop repeat-firing guns and cannons that could fire continuously, as well as large batteries of guns put together to enhance their firepower.

By the time of the Ming, gunpowder weapons were so ubitiqious that:

a battalion in the fifteenth century Chinese army had up to 40 cannon batteries, 3600 thunder-bolt shells, 160 cannons, 200 large and 328 small "grapeshot" cannons, 624 handguns, 300 small grenades, some 6.97 tons of gunpowder and no less than 1,051, 600 bullets, each of 0.8 ounces. Needham remarked that this was "quite some firepower" and the total weight of the weapons were 29.4 tons.

Bombs, grenades and mines

High explosive bombs were another innovation developed by the Chinese in the tenth century. These consisted largely of round objects covered with paper or bamboo filled with gunpowder that would explode upon contact and set fire to anything flammable. These weapons, known as "thunderclap bombs" were used by defenders in sieges on attacking enemies and also by trebuchets who hurled huge numbers of them onto the enemy. A new improved version of these bombs, called the "thunder-crash" bomb, was introduced in the 13th century that was covered in cast iron, highly explosive and hurled shrapnel at the enemy. These weapons were not only used by Song China, but also its Jur'chen and Mongol enemies. In the history of the Jur'chen Jin dynasty, the use of cast-iron gunpowder bombs against the Mongols is described:

Among the weapons of the defenders there was the heaven-shaking thundercrash bomb. It consisted of gunpowder put into an iron container; then when the fuse was lit and the projectile shot off there was a great explosion the noise whereof was like thunder, audible for more than a hundred li ..... When these reached the trenches where the Mongols were making their dugout, the bombs were set off, with the result that the cowhide and the attacking soldiers were all blown to bits... These thundercrash bombs and flying fire-spears (fire lance) were the only two weapons the Mongol soldiers were really afraid of.

A memorandum written in 1257 by Song officials recorded that cast-iron gunpowder bombs were being produced at the rate of ten or twenty thousand a month and being sent to the front lines against the Mongol invasions, though officials complained that there were insufficient supplies of bombs and fire-lanaces available to halt the Mongol advance.

By the time of the Ming Dynasty, Chinese technology had progressed to making large land mines, in which many of them were deployed on the northern border. Sinologist Joseph Needham speculates that the triggers for these mines were the ancestor of triggers for flintlock muskets. Sea mines were also used by the Chinese, even as late as the Opium wars, in which they were used against the British near Canton.

Flamethrower

Although the Byzantines had been using a single-piston proto-flame thrower as early as the 7th century, the first true flamethrower capable of emitting a continuous stream of fire was introduced in China around 900 CE. Flamethrowers were employed in naval combat in the Yangtze river, and large-scale use of the flamethrower is recorded in 975, when the Southern Tang navy employed flamethrowers against Song naval forces, but the wind blew the other way, causing the Southern Tang fleet to be immolated, and allowing the Song to conquer South China. During Song times, the flamethrower was used not only in naval combat but also in defense of cities, where they were placed on the city walls to incinerate any attacking soldiers.

Rockets

The first rockets used in combat were in 1206, by Song forces defending the city of Xiangyang from Jur'chen Jin. During the Ming dynasty, the design of rockets were further refined and multi-stage rockets and large batterise of rockets were produced. It was recorded that as many as 320 rockets were fitted into a single battery, allowing massive amounts of firepower to be deployed. Portable personal rocket launchers were also deployed. Multi-stage rockets were introduced for naval combat, and their range was stated at 1000 feet. Like other technology, knowledge of rockets were transmitted to the Middle East and the West through the Mongols, where they were described by Arabs as "Chinese arrows".

Infantry

In the 2nd century BCE, the Han began to produce steel from cast iron. Its strength allowed the Chinese to develop weapons superior in quality to the iron weapons used by other nations. New steel weapons were manufactured that gave Chinese infantry an edge in close-range fighting, though swords and blades were also used. In addition, the Chinese infantry were given extremely heavy armor in order to withstand cavalry charges, some 29.8 kg of armor during the Song Dynasty. Units in southern China were often equipped with an innovation, paper armour, which was much lighter and was said to be able to withstand firearms.

Cavalry

The cavalry was equipped with heavy armor in order to crush a line of infantry, though light cavalry was used for reconnaissance. However, Chinese armies lacked horses and their cavalry were often inferior to their horse archer opponents. Therefore, in most of these campaigns, the cavalry had to rely on the infantry to provide support. In the latter half of the Han dynasty, fully armored cataphracts were introduced in combat. An important innovation of the Chinese was the invention of the stirrup, which allowed cavalrymen to be much more effective in combat; this innovation later spread to Western Europe via the Rouran, also known as the Avars. However, some believe northern nomads were responsible for this innovation..

Some authors claim the spread of the stirrup to Europe stimulated development of the medieval knights which characterized feudal Europe. Lynn White's feudalization thesis meanwhile has largely been discounted in the Great Stirrup Controversy by historians such as Bernard Bachrach, although it has been pointed out that the Carolingian riders may have been the most expert cavalry of all at its use.

Chemical weapons

The Chinese were the first nation to deploy poison gas in combat, having deployed gases as early as the 5th century BCE. During the Han Dynasty, state manufacturers were producing stink bombs and tear gas bombs that were used effectively to suppress a revolt in 178 CE. Poisionous materials were also employed in rockets and crossbow ammunition to increase their effectiveness.

Logistics

The Chinese armies also benefited from a logistics system that could supply hundreds of thousands of men at a time. An important innovation by the Chinese was the introduction of an efficient horse harness in the 4th century BCE, strapped to the chest instead of the neck, an innovation later expanded to a collar harness. A horse with a collar harness could pull a ton and a half, while a horse with the earlier throat harness could only pull half a ton. This innovation, along with the wheelbarrow, allowed large-scale transportation to occur, allowing huge armies numbering hundreds of thousands of men in the field. By contrast, historian Robert Temple notes that contemporary Rome was unable even to transport grain from Northern Italy to Rome and had to depend on ship-carried Egyptian grain, due to a lack of a good harness.

Chinese armies were also backed by a vast complex of arms-producing factories. Scholars state that the military-industrial complex is a "two thousand year old phenomenon in China". State-owned factories turned out weapons by the thousands, though some dynasties (such as the Later Han) privatized their arms industry and acquired weapons from private merchants.

Command

In early Chinese armies, command of the armies were based on birth rather than merit. For example, for the state of Qi in the Spring and Autumn Era (771 BCE-479 BCE), the command of the armies were delegated to the ruler, the crown prince, and the second son. By the warring states, however, generals were appointed based on merit rather than birth, and the majority of generals came from talented individuals who gradually rose through the ranks.

Nevertheless, Chinese armies were sometimes commanded by individuals other than generals. For example, during the Tang Dynasty, the emperor instituted "Army supervisors" who spied on the generals and interfere in command. Although most of these practices were short-lived, they were disruptive to the efficiency of the army.

Major battles and campaigns

- Battle of Muye

- Battle of Chengpu

- Battle of Jinyang

- Battle of Changping

- Battle of Gaixia

- Sino-Xiongnu War

- Battle of Mayi

- Battle of Mobei

- Battle of Chibi

- Wu Hu uprising

- Wei-Jie war

- Battle of Fei

- Liu Yu's expeditions

- Battle of Shayuan

- Battle of Salsu

- Tang-Gokturk wars

- Battle of Baekgang

- Battle of Talas

- Battle of Suiyang

- Battle of Tangdao

- Battle of Caishi

- Battle of Xiangyang

- Mongol conquest of the Song Dynasty

- Yongle's expeditions against Mongolia

- Imjin War

- Opium wars

- Sino-French war

- First Sino-Japanese war

See also

References

- Li and Zheng (2001), 2

- H. G. Creel: "The Role of the Horse in Chinese History", The American Historical Review, Vol. 70, No. 3 (1965), pp. 647-672 (649f.)

- Frederic E. Wakeman: The great enterprise: the Manchu reconstruction of imperial order in seventeenth-century China, Vol. 1 (1985), ISBN 9780520048041, p. 77

- Griffith (2006), 1

- ^ Griffith (2006), 21-27

- ^ Li and Zheng (2001), 212

- Li and Zheng (2001), 1134

- Griffith (2006), 59

- Griffith (2006), 23-24

- Griffith (2006), 49-61

- New Scientist. Reed Business Information. Nov 16, 1978. p. 539. ISBN ISSN 0262-4079. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Griffith (2006), 55

- Graff (2002), 22

- Li and Zheng(2001), 212-247

- Li and Zheng (2001), 247-249

- de Crespigny (2007), 564–565 & 1234; Hucker (1975), 166

- Bielenstein (1980), 114.

- Ebrey (1999), 61

- Ebrey (1999), 62-63.

- ^ Li and Zheng (2001), 428-434

- Li and Zheng (2001), 648-649

- Ebrey(1999), 63

- Li and Zheng (2001), 554

- Ebrey (1999), 76

- Ji et al (2005), Vol 2, 19

- Ebrey (1999), 92

- Li and Zheng (2001), 822

- Li and Zheng (2001), 859

- Li and Zheng (2001), 868

- Ebrey (1999), 99

- Li and Zheng (2001), 877

- ^ Ji et al (2005), Vol 2, 84

- James P. Delgado (2008). Khubilai Khan's lost fleet: in search of a legendary armada. University of California Press. p. 72. ISBN 0520259769. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - Stephen Turnbull (2003). Genghis Khan & the Mongol Conquests 1190-1400. Osprey Publishing. p. 95. ISBN 1841765236. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - Paul E. Chevedden: "Black Camels and Blazing Bolts: The Bolt-Projecting Trebuchet in the Mamluk Army", Mamluk Studies Review Vol. 8/1, 2004, pp.227-277 (232f.)

- Ebrey (1999), 140

- Ji et al (2005), Vol 3, 25

- Dreyer (1988), 104

- Dreyer (1988), 105

- Li and Zheng (2001), 950

- ^ Donald F. Lach, Edwin J. Van Kley (1998). Asia in the Making of Europe: A Century of Advance : East Asia. University of Chicago Press. p. 1821. ISBN 0226467694. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - Rev. WM. Campbell: "Formosa under the Dutch. Described from contemporary Records with Explanatory Notes and a Bibliography of the Island", originally published by Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd. London 1903, republished by SMC Publishing Inc. 1992, ISBN 957-638-083-9, p. 452

- Rev. WM. Campbell: "Formosa under the Dutch. Described from contemporary Records with Explanatory Notes and a Bibliography of the Island", originally published by Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd. London 1903, republished by SMC Publishing Inc. 1992, ISBN 957-638-083-9, p. 450f.

- Andrade, Tonio. "How Taiwan Became Chinese Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century Chapter 11 The Fall of Dutch Taiwan". Columbia University Press. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Lynn A. Struve (1998). Voices from the Ming-Qing cataclysm: China in tigers' jaws. Yale University Press. p. 232. ISBN 0300075537. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - Rev. WM. Campbell: "Formosa under the Dutch. Described from contemporary Records with Explanatory Notes and a Bibliography of the Island", originally published by Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd. London 1903, republished by SMC Publishing Inc. 1992, ISBN 957-638-083-9, p. 421

- Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. China Branch (1895). Journal of the China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society for the year ..., Volumes 27-28. The Branch. p. 44. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. North-China Branch (1894). Journal of the North-China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Volumes 26-27. The Branch. p. 44. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Li and Zheng (2001), 1018

- Li and Zheng (2001), 1082

- Li and Zheng (2001), 1133

- Griffith (2006), 67

- Griffith (2006), 65

- ^ Griffith (2006), 63

- ^ Griffith (2006), 62

- Griffith (2006), 64

- Griffith (2006), 106

- ^ Temple (1986), 248

- Temple 1986, p. 218

- ^ Temple 1986, p. 220

- Temple 1986, p. 222

- ^ Temple 1986, p. 223

- Michael Roberts (1967): The Military Revolution, 1560-1660 (1956), reprint in Essays in Swedish History, London, pp. 195–225 (217)

- Parker, Geoffrey (1976): "The "Military Revolution," 1560-1660. A Myth?", The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 48, No. 2, pp. 195–214

- Kennedy, Paul (1987): The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers. Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000, Vintage Books, ISBN 0-679-72019-7, p. 45

- Temple 1986, p. 224

- Temple 1986, p. 242

- Temple 1986, p. 243

- ^ Temple 1986, p. 245

- Gwei-Djen, Lu; Joseph Needham, Phan Chi-Hsing (July 1988). "The Oldest Representation of a Bombard". Technology and Culture (Johns Hopkins University Press) 29 (3): 594–605. doi:10.2307/3105275. http://jstor.org/stable/3105275.

- Temple 1986, p. 247

- Temple 1986, p. 232

- Temple 1986, p. 234

- Temple 1986, p. 235

- Temple 1986, p. 237

- Joseph Needham: „Science and Civilisation in China“,Cambridge University Press, 1974, Vol. 7, ISBN 0521303583, p.84

- Temple 1986, p. 229

- Temple 1986, p. 230

- Temple 1986, p. 231

- ^ Temple 1986, p. 241

- ^ Temple 1986, p. 239

- Temple 1986, p. 240

- Temple 1986, p. 49

- Li and Zheng (2001), 288

- Temple 1986, p. 83

- Li and Zheng (2001), 531

- Albert Dien: “The stirrup and its effect on Chinese military history”, Ars Orientalis, Vol. 16 (1986), pp. 33-56 (38-42)

- Albert von Le Coq: “Buried Treasures of Chinese Turkestan: An Account of the Activities and Adventures of the Second and Third German Turfan Expeditions”, London: George Allen & Unwin (1928, Repr: 1985), ISBN 0-19-583878-5

- Liu Han: “Northern Dynasties Tomb Figures of Armored Horse and Rider”, K'ao-ku, No. 2, 1959, pp.97-100

- Temple (1986), 89

- Bernard S. Bachrach: "Medieval Siege Warfare: A Reconnaissance", The Journal of Military History, Vol. 58, No. 1 (Jan., 1994), pp. 119-133 (130)

- DeVries, Kelly; Smith, Robert D. (2007): Medieval Weapons. An Illustrated History of Their Impact, Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, ISBN-13 978-1-85109-531-5, p. 71

- Temple (1986), 215

- Temple (1986), 217

- Temple (1986), 218

- ^ Temple 1986, p. 21

- Griffith (2006), 24

- Griffith (2006), 122

Sources

- Bielenstein, Hans. (1980). The Bureaucracy of Han Times. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521225108.

- de Crespigny, Rafe. (2007). A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD). Leiden: Koninklijke Brill. ISBN 9004156054.

- Dreyer, Edward H. (1988), "Military origins of Ming China", in Twitchett, Denis and Mote, Frederick W. (eds.), The Ming Dynasty, part 1, The Cambridge History of China, 7, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 58–107, ISBN 9780521243322

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43519-6 (hardback); ISBN 0-521-66991-X (paperback).

- Ji, Jianghong et al. (2005). Template:Zh icon Encyclopedia of China History Vol 1. Beijing publishing house. ISBN 7-900321-54-3.

- Ji, Jianghong et al. (2005). Template:Zh icon Encyclopedia of China History Vol 2. Beijing publishing house. ISBN 7-900321-54-3.

- Ji, Jianghong et al. (2005). Template:Zh icon Encyclopedia of China History Vol 3. Beijing publishing house. ISBN 7-900321-54-3.

- Li, Bo and Zheng Yin. (Chinese) (2001). 5000 years of Chinese history. Inner Mongolian People's publishing corp. ISBN 7-204-04420-7.

- Graff, Andrew David. (2002) Medieval Chinese Warfare: 200-900. Routledge.

- Sun, Tzu, The Art of War, Translated by Sam B. Griffith (2006), Blue Heron Books, ISBN 1-897035-35-7.

- Temple, Robert (1986), The Genius of China: 3,000 years of science, discovery and invention, Simon & Schuster Inc. ISBN 0-671-62028-2

External links

- Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery and Siege Weapons of Antiquity - An Illustrated History

- "Military Technology" Visual Sourcebook for Chinese Civilization (University of Washington)

| Science and technology in China | |

|---|---|

| History | |

| Education | |

| People | |

| Institutes and programs | |