| Revision as of 11:14, 3 November 2010 editJorisvS (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers46,766 editsm def. article← Previous edit | Revision as of 04:16, 6 November 2010 edit undoHodja Nasreddin (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Pending changes reviewers31,217 edits imageNext edit → | ||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

| After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the state-run farms were reorganized and nominally privatized. This process was ultimately destructive to the village-based economy in Chukotka, and the region has still not fully recovered. Many rural Chukchi, as well as Russians in Chukotka's villages, have survived in recent years only with the help of direct humanitarian aid. Some Chukchi have attained university degrees, becoming poets, writers, politicians, teachers, and doctors. | After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the state-run farms were reorganized and nominally privatized. This process was ultimately destructive to the village-based economy in Chukotka, and the region has still not fully recovered. Many rural Chukchi, as well as Russians in Chukotka's villages, have survived in recent years only with the help of direct humanitarian aid. Some Chukchi have attained university degrees, becoming poets, writers, politicians, teachers, and doctors. | ||

| ] ]] | |||

| ==Subsistence== | ==Subsistence== | ||

Revision as of 04:16, 6 November 2010

"Chuckcha" redirects here. For the breed of dog, see Siberian Husky. Ethnic group | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Russia | |

| Languages | |

| Russian, Chukchi | |

| Religion | |

| Shamanism, Russian Orthodoxy | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Chukotko-Kamchatkan peoples |

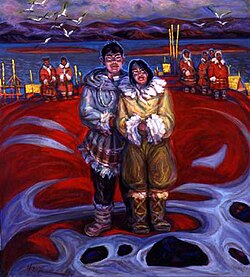

The Chukchi, or Chukchee (Template:Lang-ru (plural), чукча (singular)) are an indigenous people inhabiting the Chukchi Peninsula and the shores of the Chukchi Sea and the Bering Sea region of the Arctic Ocean within the Russian Federation. They speak the Chukchi language. The Chukchi originated from the people living around the Okhotsk Sea.

Cultural history

The majority of Chukchi reside within Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, but some also reside in the neighboring Sakha Republic to the west, Magadan Oblast to the southwest, and Koryak Autonomous Okrug to the south. Some Chukchi also reside in other parts of Russia, as well as in Europe and North America. The total number of Chukchi in the world slightly exceeds 15,000.

The Chukchi are traditionally divided into the Maritime Chukchi, who had settled homes on the coast and lived primarily from sea mammal hunting, and the Reindeer Chukchi, who nomadised in the inland tundra region with their herds of reindeer. The Russian name "Chukchi" is derived from the Chukchi word Chauchu ("rich in reindeer"), which was used by the 'Reindeer Chukchi' to distinguish themselves from the 'Maritime Chukchi,' called Anqallyt ("the sea people"). The indigenous name for a member of the Chukchi ethnic group as a whole is Luoravetlan (literally 'true person').

In Chukchi religion, every object, whether animate or inanimate, is assigned a spirit. This spirit can be either harmful or beneficial. Some of Chukchi myths reveal a dualistic cosmology. Chukchi religious practices were prohibited by the Soviet Union in the 1920s.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the state-run farms were reorganized and nominally privatized. This process was ultimately destructive to the village-based economy in Chukotka, and the region has still not fully recovered. Many rural Chukchi, as well as Russians in Chukotka's villages, have survived in recent years only with the help of direct humanitarian aid. Some Chukchi have attained university degrees, becoming poets, writers, politicians, teachers, and doctors.

Subsistence

In prehistoric times the Chukchi engaged in nomadic hunter gatherer modes of existence. In current times there continue to be some elements of subsistence hunting, including that of polar bears, marine mammals and reindeer. Beginning in the 1920s, the Soviets organized the economic activities of both coastal and inland Chukchi and eventually established 28 collectively run, state-owned enterprises in Chukotka. All of these were based on reindeer herding, with the addition of sea mammal hunting and walrus ivory carving in the coastal areas. Chukchi were educated in Soviet schools and today are almost 100% literate and fluent in the Russian language. Only a portion of them today work directly in reindeer herding or sea mammal hunting.

Relations with Russians

Russians first began contacting the Chukchis when they reached the Kolyma river (1643) and the Anadyr River (1649). The route from Nizhnekolymsk to the fort at Anadyrsk along the southwest of the main Chukchi area became a major trade route. The overland journey from Yakutsk to Anadyrsk took about six months.

The Chukchis were generally ignored for the next 50 years because they were warlike and had few furs. Fighting flared up around 1700 when the Russians began operating in the Kamchatka Peninsula and needed to protect their communications from the Chukchis and Koryaks. The first attempt to conquer them was made in 1701. Other expeditions were sent out in 1708, 1709 and 1711 with considerable bloodshed but little success. War was renewed in 1729, when the Chukchis defeated an expedition from Okhotsk and its commander was killed. Command passed to Major Dmitry Pavlutsky who adopted very destructive tactics, burning, killing, driving off reindeer and capturing women and children. In 1742, Saint Petersburg ordered another war in which the Chukchis and Koryaks were to be "totally extirpated". The war (1744–7) was conducted with similar brutality and ended when Pavlutsky was killed in March 1747. It is said that the Chukchis kept his head as a trophy for a number of years. There was more war in the 1750s.

In 1762, Saint Petersburg adopted a different policy. Maintaining the fort at Anadyrsk had cost some 1,380,000 rubles, but the area had returned only 29,150 rubles in taxes. Anadyrsk was abandoned in 1764. The Chukchis, no longer provoked, began to trade peacefully with the Russians. From 1788, there was an annual trade fair on the lower Kolyma. Another was established on the Angarka, a tributary of the Bolshoy Anyuy River in 1775. This trade declined in the late 19th century when American whalers and others began landing goods on the coast. The first Orthodox missionaries entered Chukchi territory some time after 1815.

Soviet Period

Apart from four Orthodox schools, there were no schools in the Chukchi land until the late 1920s. In 1926, there were 72 literate Chukchis. A Latin alphabet was introduced in 1932 and replaced with Cyrillic in 1937. In 1934, 71% of the Chukchis were still nomadic. By 1939, 95% of the coastal Chukchis were collectivized, but only 11% of the reindeer nomads. In the late 1930s, several "reindeer kings" had very large herds and employed hired labor. In 1941, 90% of the reindeer were still privately owned. So-called kulaks still roamed with their private herds up into the 1950s. After 1990, there was a major exodus of Russians.

Population estimates from Forsyth: 1700: 6,000, 1800: 8-9,000, 1926: 13,100, 1930s:12,000, 1939: 13,900, 1959: 11,700, 1979: at least 13,169.

See also

Notes

- Zolotarjov 1980: 40–41

- Anyiszimov 1981: 92–98

- C.M. Hogan, 2008

- Forsyth, James, 'A History of the Peoples of Siberia, 1992, for this and the next section

- ^ Shentalinskaia, Tatiana (2002). "Major Pavlutskii: From History to Folklore" (PDF). Slavic and East European Folklore Association Journal. 7 (1): 3–21. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

References

- Forsyth, James, 'A History of the Peoples of Siberia', 1992.

- Anyiszimov, A. F. (1981). Az ősközösségi társadalom szellemi élete (in Hungarian). Budapest: Kossuth Könyvkiadó. ISBN 963 09 1843 9. Title means: “The spiritual life of primitive society”. The book is composed out of the translations of the following two originals: Анисимов, Ф. А. (1966). Духовная жизнь первобытново общества (in Russian). Москва • Ленинград: Наука. The other one: Анисимов, Ф. А. (1971). Исторические особенности первобытново мышления (in Russian). Москва • Ленинград: Наука.

- Patty A. Gray (2005). The Predicament of Chukotka's Indigenous Movement: Post-Soviet Activism in the Russian Far North. Cambridge.

- C. Michael Hogan (2008) Polar Bear: Ursus maritimus, Globaltwitcher.com, ed. Nicklas Stromberg

- Anna Kerttula (2000). Antler on the Sea. Cornell University Press.

- "The Chukchis". The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire.

- "All Things Arctic".

- Zolotarjov, A.M. (1980). "Társadalomszervezet és dualisztikus teremtésmítoszok Szibériában". In Hoppál, Mihály (ed.). A Tejút fiai. Tanulmányok a finnugor népek hitvilágáról (in Hungarian). Budapest: Európa Könyvkiadó. pp. 29–58. ISBN 963 07 2187 2. Chapter means: “Social structure and dualistic creation myths in Siberia”; title means: “The sons of Milky Way. Studies on the belief systems of Finno-Ugric peoples”.

- Ĉukĉ, Even, Jukaghir. Kolyma: Chants de nature et d'animaux. Sibérie 3. Musique du monde.

External links

- Chukchee Mythology by Waldemar Bogoras

- Bogoraz, Waldemar (1904). The Chukchee. Vol. 11 Part 1: Material culture (pdf). Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History. Leiden • New York: E. J. Brill ltd • G. E. Stechert & Co.

- Bogoraz, Waldemar (1907). The Chukchee. Vol. 11 Part 2: Religion (pdf). Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History. Leiden • New York: E. J. Brill ltd • G. E. Stechert & Co.

- Bogoraz, Waldemar (1909). The Chukchee. Vol. 11 Part 3: Social organization (pdf). Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History. Leiden • New York: E. J. Brill ltd • G. E. Stechert & Co.

- Bogoraz, Waldemar (1910). Chukchee Mythology (pdf). Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History. Leiden • New York: E. J. Brill ltd • G. E. Stechert & Co.

- Siimets, Ülo (2006). "The Sun, the Moon and Firmament in Chukchi Mythology and on the Relations of Celestial Bodies and Sacrifices" (pdf). Electronic Journal of Folklore. 32. Estonian Folklore: 129–156.

Template:Cultures in standard cross-cultural sample

Categories: