| Revision as of 11:49, 4 March 2006 editDahn (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers147,831 editsmNo edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 11:50, 4 March 2006 edit undoDahn (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers147,831 edits catNext edit → | ||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

| {{Russianart}} | {{Russianart}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 11:50, 4 March 2006

Mir iskusstva (Template:Lang-ru; English translation: World of Art) was a Russian magazine and the artistic movement it inspired and embodied, which was a major influence on the Russians who helped revolutionize European art during the first decade of the 20th century. From 1909, many of the miriskusniki (i.e., members of the movement) also contributed to the Ballets Russes company operating in Paris. Paradoxically, few Western Europeans actually saw issues of the magazine itself.

History

The magazine was cofounded in 1899 in St. Petersburg by Alexandre Benois, Léon Bakst, and Sergei Diaghilev. They aimed at assailing low artistic standards of the obsolescent Peredvizhniki school and promoting artistic individualism and other principles of Art Nouveau.

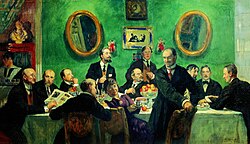

Apart from three founding fathers, active members of the World of Art included Mikhail Dobuzhinsky, Eugene Lansere, and Konstantin Somov. Exhibitions organized by the World of Art attracted many illustrious painters from Russia and abroad, notably Mikhail Vrubel, Mikhail Nesterov, and Isaac Levitan.

In 1903, Mir iskusstva was transformed into the Union of Russian Artists which continued officially until 1910 and unofficially until 1924. The Union included painters (Valentin Serov, Konstantin Korovin, Boris Kustodiev, Zinaida Serebryakova), illustrators (Ivan Bilibin, Konstantin Somov), restorators (Igor Grabar), and scenic designers (Nicholas Roerich, Serge Sudeikin).

Art

Like the English pre-Raphaelites before them, Benois and his friends were disgusted with anti-aesthetic nature of modern industrial society and sought to consolidate all Neo-Romantic Russian artists under the auspices of fighting Positivism in art.

Like the Romantics before them, the miriskusniki promoted understanding and conservation of the art of previous epochs, particularly traditional folk art and the 18th-century rococo. Antoine Watteau was probably the single artist whom they admired the most.

Such Revivalist projects were treated by the miriskusniki humorously, in a spirit of self-parody. They were fascinated with masks and marionettes, with carnaval and puppet theater, with dreams and fairy-tales. Everything grotesque and playful appealed to them more than the serious and emotional. Their favorite city was Venice, so much so that Diaghilev and Stravinsky selected it as a place of their burial.

As for media, the miriskusniki preferred light, airy effects of watercolor and gouache to full-scale oil paintings. Seeking to bring art into every house, they often designed interiors and books. Bakst and Benois revolutionized theatrical design with their ground-breaking decor for Cléopâtre (1909), Carnaval (1910), Petrushka (1911), and L'après-midi d'un faune (1912).