| Revision as of 11:20, 11 May 2011 editEmausBot (talk | contribs)Bots, Template editors2,853,686 editsm r2.6.4) (robot Adding: udm:Секвойядендрон← Previous edit | Revision as of 11:23, 18 May 2011 edit undoΔ (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers35,263 editsm adjusting filename after renameNext edit → | ||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

| ==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

| ]. Note the large fire scar at the base of the right-hand tree; fires do not kill the trees but do remove competing thin-barked species, and aid giant sequoia regeneration.]] | ]. Note the large fire scar at the base of the right-hand tree; fires do not kill the trees but do remove competing thin-barked species, and aid giant sequoia regeneration.]] | ||

| The giant sequoias are having difficulty reproducing in their original habitat (and very rarely reproduce in cultivation) due to the seeds only being able to grow successfully in mineral soils in full sunlight, free from competing vegetation. Although the seeds can germinate in moist needle ] in the spring, these seedlings will die as the duff dries in the summer. They therefore require periodic ] to clear competing vegetation and soil humus before successful regeneration can occur. Without fire, shade-loving species will crowd out young sequoia seedlings, and sequoia seeds will not germinate. When fully grown, these trees typically require large amounts of water and are therefore often concentrated near streams. | The giant sequoias are having difficulty reproducing in their original habitat (and very rarely reproduce in cultivation) due to the seeds only being able to grow successfully in mineral soils in full sunlight, free from competing vegetation. Although the seeds can germinate in moist needle ] in the spring, these seedlings will die as the duff dries in the summer. They therefore require periodic ] to clear competing vegetation and soil humus before successful regeneration can occur. Without fire, shade-loving species will crowd out young sequoia seedlings, and sequoia seeds will not germinate. When fully grown, these trees typically require large amounts of water and are therefore often concentrated near streams. | ||

Revision as of 11:23, 18 May 2011

| Sequoiadendron giganteum | |

|---|---|

| |

| The "Grizzly Giant" tree in Mariposa Grove, Yosemite National Park | |

| Conservation status | |

Vulnerable (IUCN 2.3) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Cupressaceae |

| Subfamily: | Sequoioideae |

| Genus: | Sequoiadendron |

| Species: | S. giganteum |

| Binomial name | |

| Sequoiadendron giganteum (Lindl.) J.Buchh. | |

Sequoiadendron giganteum (giant sequoia, Sierra redwood, Sierran redwood, or Wellingtonia) is the sole living species in the genus Sequoiadendron, and one of three species of coniferous trees known as redwoods, classified in the family Cupressaceae in the subfamily Sequoioideae, together with Sequoia sempervirens (Coast Redwood) and Metasequoia glyptostroboides (Dawn Redwood). The common use of the name "sequoia" generally refers to Sequoiadendron, which occurs naturally only in groves on the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California.

The genus Sequoiadendron includes a single extinct species, S. chaneyi.

Description

Giant Sequoias are the world's largest trees in terms of total volume (technically, only 7 living Giant Sequoia exceed the 42,500 cubic feet (1,200 m) of the Lost Monarch Coast Redwood tree; see Largest trees). They grow to an average height of 50–85 metres (164–279 ft) and 6–8 metres (20–26 ft) in diameter. Record trees have been measured to be 94.8 metres (311 ft) in height and 17 metres (56 ft) in diameter. The oldest known Giant Sequoia based on ring count is 3,500 years old. Sequoia bark is fibrous, furrowed, and may be 90 centimetres (3.0 ft) thick at the base of the columnar trunk. It provides significant fire protection for the trees. The leaves are evergreen, awl-shaped, 3–6 mm long, and arranged spirally on the shoots. The seed cones are 4–7 cm long and mature in 18–20 months, though they typically remain green and closed for up to 20 years; each cone has 30-50 spirally arranged scales, with several seeds on each scale giving an average of 230 seeds per cone. The seed is dark brown, 4–5 mm long and 1 mm broad, with a 1 mm wide yellow-brown wing along each side. Some seed is shed when the cone scales shrink during hot weather in late summer, but most seeds are liberated when the cone dries from fire heat or is damaged by insects (see Ecology, below).

Giant sequoia regenerates by seed. Trees up to about 20 years old may produce stump sprouts subsequent to injury. Giant sequoia of all ages may sprout from the bole when old branches are lost to fire or breakage, but (unlike coast redwood) mature trees do not sprout from cut stumps. Young trees start to bear cones at the age of 12 years.

At any given time, a large tree may be expected to have approximately 11,000 cones. The upper part of the crown of any mature Giant Sequoia invariably produces a greater abundance of cones than its lower portions. A mature giant sequoia has been estimated to disperse from 300,000-400,000 seeds per year. The winged seeds may be carried up to 180 m (600 ft) from the parent tree.

Lower branches die fairly readily from shading, but trees less than 100 years old retain most of their dead branches. Trunks of mature trees in groves are generally free of branches to a height of 20–50 m, but solitary trees will retain low branches.

Distribution

Further information: List of giant sequoia grovesThe natural distribution of giant sequoia is restricted to a limited area of the western Sierra Nevada, California. It occurs in scattered groves, with a total of 68 groves (see list of sequoia groves for a full inventory), comprising a total area of only 144.16 square kilometres (35,620 acres). Nowhere does it grow in pure stands, although in a few small areas stands do approach a pure condition. The northern two-thirds of its range, from the American River in Placer County southward to the Kings River, has only eight disjunct groves. The remaining southern groves are concentrated between the Kings River and the Deer Creek Grove in southern Tulare County. Groves range in size from 12.4 square kilometres (3,100 acres) with 20,000 mature trees, to small groves with only six living trees. Many are protected in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks and Giant Sequoia National Monument.

Giant sequoia is usually found in a humid climate characterized by dry summers and snowy winters. Most giant sequoia groves are on granitic-based residual and alluvial soils. The elevation of the giant sequoia groves generally ranges from 1,400–2,000 metres (4,600–6,600 ft) in the north, and 1,700–2,150 metres (5,580–7,050 ft) to the south. Giant sequoia generally occurs on the south facing side of northern mountains, and on the northern face of more southern slopes.

High levels of reproduction are not necessary to maintain the present population levels. Few groves, however, have sufficient young trees to maintain the present density of mature giant sequoias for the future. The majority of giant sequoias are currently undergoing a gradual decline in density since the European settlement days.

Ecology

The giant sequoias are having difficulty reproducing in their original habitat (and very rarely reproduce in cultivation) due to the seeds only being able to grow successfully in mineral soils in full sunlight, free from competing vegetation. Although the seeds can germinate in moist needle humus in the spring, these seedlings will die as the duff dries in the summer. They therefore require periodic wildfire to clear competing vegetation and soil humus before successful regeneration can occur. Without fire, shade-loving species will crowd out young sequoia seedlings, and sequoia seeds will not germinate. When fully grown, these trees typically require large amounts of water and are therefore often concentrated near streams.

Fires also bring hot air high into the canopy via convection, which in turn dries and opens the cones. The subsequent release of large quantities of seeds coincides with the optimal post-fire seedbed conditions. Loose ground ash may also act as a cover to protect the fallen seeds from ultraviolet radiation damage.

Due to fire suppression efforts and livestock grazing during the early and mid 20th century, low-intensity fires no longer occurred naturally in many groves, and still do not occur in some groves today. The suppression of fires also led to ground fuel build-up and the dense growth of fire-sensitive White Fir. This increased the risk of more intense fires that can use the firs as ladders to threaten mature Giant Sequoia crowns. Natural fires may also be important in keeping carpenter ants in check.

In 1970 the National Park Service began controlled burns of its groves to correct these problems. Current policies also allow natural fires to burn. One of these untamed burns severely damaged the second-largest tree in the world, the Washington tree, in September 2003, 45 days after the fire started. This damage made it unable to withstand the snowstorm of January 2005, leading to the collapse of over half the trunk.

In addition to fire, there are also two animal agents for giant sequoia seed release. The more significant of the two is a longhorn beetle (Phymatodes nitidus) that lays eggs on the cones, into which the larvae then bore holes. This cuts the vascular water supply to the cone scales, allowing the cones to dry and open for the seeds to fall. Cones damaged by the beetles during the summer will slowly open over the next several months. Some research indicates that many cones, particularly higher in the crowns, may need to be partially dried by beetle damage before fire can fully open them. The other agent is the Douglas Squirrel (Tamiasciurus douglasi) that gnaws on the fleshy green scales of younger cones. The squirrels are active year round, and some seeds are dislodged and dropped as the cone is eaten.

Discovery and naming

The giant sequoia was well known to Native American tribes living in its area. Native American names for the species include Wawona, Toos-pung-ish and Hea-mi-withic, the latter two in the language of the Tule River Tribe.

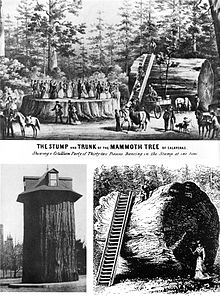

The first reference to the giant sequoia by Europeans is in 1833, in the diary of the explorer J. K. Leonard; the reference does not mention any locality, but his route would have taken him through the Calaveras Grove. This discovery was not publicized. The next European to see the species was John M. Wooster, who carved his initials in the bark of the 'Hercules' tree in the Calaveras Grove in 1850; again, this received no publicity. Much more publicity was given to the "discovery" by Augustus T. Dowd of the Calaveras Grove in 1852, and this is commonly cited as the species' discovery. The tree found by Dowd, christened the 'Discovery Tree', was felled in 1853.

The first scientific naming of the species was by John Lindley in December 1853, who named it Wellingtonia gigantea, without realizing this was an invalid name under the botanical code as the name Wellingtonia had already been used earlier for another unrelated plant (Wellingtonia arnottiana in the family Sabiaceae). The name "Wellingtonia" has persisted in England as a common name, though is deprecated as cultural imperialism (R. Ornduff in Aune 1994). The following year, Joseph Decaisne transferred it to the same genus as the Coast Redwood, naming it Sequoia gigantea, but again this name was invalid, having been applied earlier (in 1847, by Endlicher) to the Coast Redwood. The name Washingtonia californica was also applied to it by Winslow in 1854, though this too is invalid, belonging to the palm genus Washingtonia.

In 1907 it was placed by Carl Ernst Otto Kuntze in the otherwise fossil genus Steinhauera, but doubt as to whether the giant sequoia is related to the fossil originally so named makes this name invalid.

The nomenclatural oversights were finally corrected in 1939 by J. Buchholz, who also pointed out that the giant sequoia is distinct from the coast redwood at the genus level and coined the name Sequoiadendron giganteum for it.

John Muir wrote of the species in about 1870:

Do behold the King Sequoia! Behold! Behold! seems all I can say. Some time ago I left all for Sequoia and have been and am at his feet, fasting and praying for light, for is he not the greatest light in the woods, in the world? Where are such columns of sunshine, tangible, accessible, terrestrialized?

Uses

Wood from mature giant sequoias is highly resistant to decay, but due to being fibrous and brittle, it is generally unsuitable for construction. From the 1880s through the 1920s logging took place in many groves in spite of marginal commercial returns. Due to their weight and brittleness trees would often shatter when they hit the ground, wasting much of the wood. Loggers attempted to cushion the impact by digging trenches and filling them with branches. Still, it is estimated that as little as 50 percent of the timber made it from groves to the mill. The wood was used mainly for shingles and fence posts, or even for matchsticks.

Pictures of the once majestic trees broken and abandoned in formerly pristine groves, and the thought of the giants put to such modest use, spurred the public outcry that caused most of the groves to be preserved as protected land. The public can visit an example of 1880s clear-cutting at Big Stump Grove near General Grant Grove. As late as the 1980s some immature trees were logged in Sequoia National Forest, publicity of which helped lead to the creation of Giant Sequoia National Monument.

The wood from immature trees is less brittle, with recent tests on young plantation-grown trees showing it similar to Coast Redwood wood in quality. This is resulting in some interest in cultivating Giant Sequoia as a very high-yielding timber crop tree, both in California and also in parts of western Europe, where it may grow more efficiently than Coast Redwoods. In the northwest United States some entrepreneurs have also begun growing Giant Sequoias for Christmas trees. Besides these attempts at tree farming, the principal economic uses for Giant Sequoia today are tourism and horticulture (see Cultivation, below).

Cultivation

Giant Sequoia is a very popular ornamental tree in many areas. Areas where it is successfully grown include most of western and southern Europe, the Pacific Northwest of North America north to southwest British Columbia, the southern United States, southeast Australia, New Zealand and central-southern Chile. It is also grown, though less successfully, in parts of eastern North America.

Trees can withstand temperatures of −31 °C (−25 °F) or colder for short periods of time, provided that the ground around the roots is insulated with either heavy snow or mulch. Outside its natural range, the foliage can suffer from damaging windburn.

Since its discovery a wide range of horticultural varieties have been selected, especially in Europe. There are, amongst others, weeping, variegated, pygmy, blue, grass green, and compact forms.

Europe

The Giant Sequoia was first brought into cultivation in 1853 by Scotsman John D. Matthew, who collected a small quantity of seed in the Calaveras Grove, arriving with it in Scotland in August 1853. A much larger shipment of seed collected (also in the Calaveras Grove) by William Lobb, acting for the Veitch Nursery at Budlake near Exeter, arrived in England in December 1853; seed from this batch was widely distributed throughout Europe.

Growth in Britain is very fast, with the tallest tree, at Benmore in southwest Scotland, reaching 54 metres (177 ft) at age 150 years, and several others from 50–53 m tall; the stoutest is around 12 m in girth and 4 m in diameter, in Perthshire. The Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew in London also contains a large specimen. The General Sherman of California has a volume of 1489 cubic meters; by way of comparison, the largest giant sequoias in Great Britain have volumes no larger than 90-100 cubic meters, one example being the 90 cubic meter giant in the New Forest.

Growth rates in some areas are remarkable; one young tree in Italy reached 22 metres (72 ft) tall and 88 centimetres (2.89 ft) trunk diameter in 17 years (Mitchell, 1972).

The re-introduction of the Giant Sequoia into the German forestry was realized in 1952 by two members of the German Dendrology Society E. J. Martin and Illa Martin in the Sequoiafarm Kaldenkirchen.

Growth further northeast in Europe is limited by winter cold. In Denmark, where extreme winters can reach −32 °C, the largest tree was 35 metres (115 ft) tall and 1.7 metres (5.6 ft) diameter in 1976 and is bigger today. One in Poland has purportedly survived temperatures down to −37 °C with heavy snow cover.

United States and Canada

Giant sequoias are grown successfully in the Pacific Northwest and southern US, and less successfully in eastern North America.

Giant Sequoia cultivation is very successful in the Pacific Northwest from western Oregon north to southwest British Columbia, with fast growth rates. In Washington and Oregon, it is common to find giant sequoias that have been successfully planted in both urban and rural areas. In the Seattle area, large specimens (over 90 feet) are fairly common and exist in several city parks and many private yards (especially east Seattle including Capitol Hill, Washington Park, & Leschi/Madrona).

In the northeastern US there has been some limited success in growing the species, but growth is much slower there, and it is prone to Cercospora and Kabatina fungal diseases due to the hot, humid summer climate there. A tree at Blithewold Gardens, in Bristol, Rhode Island is reported to be 27 metres (89 ft) tall, reportedly the tallest in the New England states. The tree at the Tyler Arboretum in Delaware County, Pennsylvania at 29.1 metres (95 ft) may be the tallest in the northeast. Specimens also grow in the Arnold Arboretum in Boston, Massachusetts (planted 1972, 18 m tall in 1998), at Longwood Gardens near Wilmington, Delaware, and in the Finger Lakes region of New York. Private plantings of Giant Sequoias around the Middle Atlantic States are not uncommon. Since 2000, a small amateur experimental planting has been underway in the Lake Champlain valley of Vermont at the Vermont Experimental Cold-Hardy Cactus Garden where winter temperatures can reach −37 °C with variable snowcover.

A cold-tolerant cultivar 'Hazel Smith' selected in about 1960 is proving more successful in the northeastern U.S.A. This clone was the sole survivor of several hundred seedlings grown at a nursery in New Jersey.

Australia

The Ballarat Botanical Gardens contain a significant collection, many of them about 150 years old. Jubilee Park and the Hepburn Mineral Springs Reserve in Daylesford, Cook Park in Orange, New South Wales and Carisbrook's Deep Creek park in Victoria both have specimens. In Tasmania specimens are to be seen in private and public gardens, as they were popular in the mid Victorian era. The Westbury Village Green has mature specimens with more in Deloraine. The Tasmanian Arboretum contains young wild collected material. The National Arboretum Canberra has begun a grove.

New Zealand

Several impressive specimens of Sequoiadendron giganteum exist throughout the South Island of New Zealand. Notable examples include a set of trees in a public park of Picton, as well as robust specimens in the public and botanical parks of Queenstown.

Largest trees

As of 2009, the largest Giant Sequoias (all located within California) by volume are:

| Rank | Tree Name | Grove | Height | Girth at ground | Volume | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ft) | (m) | (ft) | (m) | (ft³) | (m³) | |||

| 1 | General Sherman | Giant Forest | 274.9 | 83.8 | 102.6 | 31.3 | 52,508 | 1,486.9 |

| 2 | General Grant | General Grant Grove | 268.1 | 81.7 | 107.5 | 32.8 | 46,608 | 1,319.8 |

| 3 | President | Giant Forest | 240.9 | 73.4 | 93.0 | 28.3 | 45,148 | 1,278.4 |

| 4 | Lincoln | Giant Forest | 255.8 | 78.0 | 98.3 | 30.0 | 44,471 | 1,259.3 |

| 5 | Stagg | Alder Creek | 243.0 | 74.1 | 109.0 | 33.2 | 42,557 | 1,205.1 |

| 6 | Boole | Converse Basin | 268.8 | 81.9 | 113.0 | 34.4 | 42,472 | 1,202.7 |

| 7 | Genesis | Mountain Home Grove | 253.0 | 77.1 | 85.3 | 26.0 | 41,897 | 1,186.4 |

| 8 | Franklin | Giant Forest | 223.8 | 68.2 | 94.8 | 28.9 | 41,280 | 1,168.9 |

| 9 | King Arthur | Garfield Grove | 270.3 | 82.4 | 104.2 | 31.8 | 40,656 | 1,151.2 |

| 10 | Monroe | Giant Forest | 247.8 | 75.5 | 91.3 | 27.8 | 40,104 | 1,135.6 |

| 11 | Robert E. Lee | General Grant Grove | 254.7 | 77.6 | 88.3 | 26.9 | 40,102 | 1,135.6 |

| 12 | J. Adams | Giant Forest | 250.6 | 76.4 | 83.3 | 25.4 | 38,956 | 1,103.1 |

| 13 | Ishi Giant | Kennedy Grove | 248.1 | 75.6 | 105.1 | 32.0 | 38,156 | 1,080.5 |

| 14 | Column Tree | Giant Forest | 243.8 | 74.3 | 93.0 | 28.3 | 37,295 | 1,056.1 |

| 15 | Summit Road Tree | Mountain Home Grove | 244.0 | 74.4 | 82.2 | 25.1 | 36,600 | 1,036.4 |

| 16 | Euclid | Mountain Home Grove | 272.7 | 83.1 | 83.4 | 25.4 | 36,122 | 1,022.9 |

| 17 | Washington | Mariposa Grove | 236.0 | 71.9 | 95.7 | 29.2 | 35,901 | 1,016.6 |

| 18 | General Pershing | Giant Forest | 246.0 | 75.0 | 91.2 | 27.8 | 35,855 | 1,015.3 |

| 19 | Diamond Tree | Atwell Mill Grove | 286.0 | 87.2 | 95.3 | 29.0 | 35,292 | 999.4 |

| 20 | Adam | Mountain Home Grove | 247.4 | 75.4 | 94.2 | 28.7 | 35,017 | 991.6 |

- The General Sherman tree is estimated to weigh about 2100 tonnes.

- The Washington Tree was previously the second largest tree with a volume of 47,850 cubic feet (1,355 m), but after losing over half its trunk in January 2005 it is no longer of great size.

- The trees named "Franklin", "Column", "Monroe", "Hamilton" and "Adams" were named by Wendell Flint and others, these five are now included on the official map of giant forest, where they are all situated.

- The Hazelwood Tree (not listed above) had a volume of 36,228 cubic feet (1,025.9 m) before losing half its trunk in a lightning storm in 2002, if it were still at full size it would currently be the 16th largest giant sequoia on earth.

Giant Sequoia superlatives

Largest

- General Sherman - Giant Forest - 52,508 cubic feet (1,486.9 m)

Tallest

- Unnamed Tree - Redwood Mountain Grove - 311 feet (95 m)

Oldest

- Examples in Converse basin, Mountain home grove and Giant forest - 3500 years or more.

Largest Girth

- Waterfall Tree - Alder Creek Grove - 155 feet (47 m) - tree with enormous basal buttress on very steep ground.

Greatest Base Diameter

- Waterfall Tree - Alder Creek Grove - 57 feet (17 m) - tree with enormous basal buttress on very steep ground.

- Tunnel Tree - Atwell Mill Grove - 57 feet (17 m) - tree with a huge flared base, that has burned all the way through.

Greatest Mean Diameter at Breast Height

- General Grant - General Grant Grove - 29.0 feet (8.8 m)

Largest Limb

- Arm Tree - Atwell Mill, East Fork Grove - 12.8 feet (3.9 m) in diameter

Thickest Bark

- 3 feet (0.91 m) or more

Source:

See also

- List of giant sequoia groves

- Metasequoia glyptostroboides - Dawn Redwood

- Mother of the Forest

- Old growth forest

- Sequoia sempervirens - Coast Redwood or California Redwood

- The House (trees)

Notes

- Daniel L. Axelrod, 1959. Late Cenozoic evolution of the Sierran Bigtree forest. Evolution 13(1): 9–23.

- ^ Flint 2002

- ^ Farquhar, Francis P. (1925). "Discovery of the Sierra Nevada". California Historical Society Quarterly. 4 (1): 3–58., Yosemite.ca.us

- Redwood World - Redwoods in the British Isles, redwoodworld.co.uk

- "Species Level Browse Results". NurseryGuide.com.

- "The History of Cluny – The Plant Collectors". clunyhousegardens.com. Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- Christopher J. Earle. "Sequoiadendron giganteum (Lindley) Buchholz 1939". University of Hamburg. Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- Tree Register of the British Isles, tree-register.org

- Die Wiedereinführung des Mammutbaumes (Sequoiadendron giganteum) in die deutsche Forstwirtschaft. In: Mitteilungen der Deutschen Dendrologischen Gesellschaft. Vol. 75. pp. 57–75. Ulmer. Stuttgart 1984, ISBN 3-8001-8308-0

- "Mansion and History". Blithewold Mansion, Gardens, and Arboretum.

- "Gardens". Blithewold Mansion, Gardens, and Arboretum.

- Big Trees Of Pennsylvania: Sequoiadendron - Giant Sequoia, pabigtrees.com

- Sphaydenphotography.com

- The volume figures have a low degree of accuracy (at best about ±14 m³), due to difficulties in measurement; stem diameter measurements are taken at a few set heights up the trunk, and assume that the trunk is circular in cross-section, and that taper between measurement points is even. The volume measurements also do not take cavities into account. The measurements are trunk-only, and do not include the volume of wood in the branches or roots.

- Not the famous tree from Giant Forest but another tree by the same name, situated in Mariposa Grove.

- Fry & White 1938

References

- Template:IUCN2006 Listed as Vulnerable (VU A1cd v2.3)

- Aune, P. S., ed. (1994). Proceedings of the Symposium on Giant Sequoias. US Dept. of Agriculture Forest Service (Pacific Southwest Research Station) General Technical Report PSW-GTR-151.

- Flint, W.D. (2002). To Find The Biggest Tree. Sequoia Natural History Association, Inc. ISBN 1878441094.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fry, W.; White, J.B. (1938). Big Trees. Stanford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Alan Mitchell (1972). Conifers in the British Isles. Forestry Commission Booklet 33. HMSO.

- Alan Mitchell (1996). Alan Mitchell's Trees of Britain. HarperCollins ISBN 0-00-219972-6.

- Harvey, H. T., Shellhammer, H. S., & Stecker, R. E. (1980). Giant sequoia ecology. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Scientific Monograph Series 12. Washington, DC. 182 p.

- Kilgore, B. (1970). "Restoring Fire to the Sequoias". National Parks and Conservation Magazine. 44 (277): 16–22.

External links

- Complete Largest & Tallest sequoiadendron giganteum archive - from the Tall Trees Club, landmarktrees.net

- ARKive: Sequoiadendron giganteum, akrive.org

- Gymnosperm Database - Sequoiadendron giganteum, confiers.org

- Arboretum de Villardebelle - photos of cones & shoots with phenology notes, pinetum.org

- Forest Service database entry on Sequoiadendron giganteum, fs.fed.us

- Giant Sequoia Fire History in Mariposa Grove, Yosemite National Park (.pdf file!), nps.gov

- Save-the-Redwoods League, savethewoods.org

- "Sequoias of Yosemite National Park" 1949 by James W. McFarland

- Photo Tour: Giant Sequoia, Prof Stephen Sillett's webpage with photos

- Redwoodworld.co.uk giant redwoods in the U.K.

- The Giant Sequoia of the Sierra Nevada An NPS online book

- The Growing Sequoia, a project attempting to grow a sequoia from the seed, thegrowingsequoia.com

- Scenes of Wonder and Curiosity in California (1862) – The Mammoth Trees Of Calaveras, yosemite.ca.us

- Short radio episode Woody Gospel Letter in which John Muir extols "King Sequoia" from The Life and Letters of John Muir, 1924. California Legacy Project.