| Revision as of 14:31, 15 March 2006 view sourceGhollingsworth (talk | contribs)12 edits →External links← Previous edit | Revision as of 14:41, 15 March 2006 view source Monkeyman (talk | contribs)4,288 editsm →External links: Removed spam.Next edit → | ||

| Line 476: | Line 476: | ||

| * | * | ||

| * (1850-1865) | * (1850-1865) | ||

| * Free archive of 25,000 newspaper pages dedicated to Abraham Lincoln | |||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

Revision as of 14:41, 15 March 2006

- For other uses of the name Abraham Lincoln, see Abraham Lincoln (disambiguation)

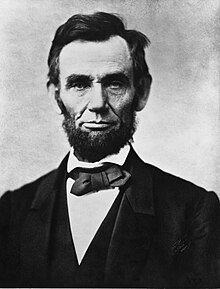

| Abraham Lincoln | |

|---|---|

| |

| 16th President | |

| In office March 4, 1861 – April 15, 1865 | |

| Vice President | Hannibal Hamlin (1861 to 1865); Andrew Johnson (March - April 1865) |

| Preceded by | James Buchanan |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Johnson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 12, 1809 Hardin County, Kentucky (now in LaRue County) |

| Died | April 15, 1865 Washington, D.C. |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Mary Todd Lincoln |

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865), sometimes called Abe Lincoln and nicknamed Honest Abe, the Rail Splitter, and the Great Emancipator, was the 16th President of the United States (1861 to 1865), and the first president from the Republican Party. Lincoln opposed the expansion of slavery and oversaw the Union war effort during the American Civil War. He selected the generals and approved their strategy; selected senior civilian officials; supervised diplomacy, patronage and party operations; rallied public opinion through messages and speeches such as the Gettysburg Address; and took personal charge of plans for the abolition of slavery and the Reconstruction of the Union. He was assassinated as the war ended.

Summary

President Lincoln was opposed to what he saw as the Slave Power and staunchly opposed its efforts to expand slavery into federal territories. His victory in the 1860 presidential election was the final straw in the deep South, where seven states seceded, formed the Confederate States of America, and took control of U.S. forts and other properties within their boundaries, setting the stage for the American Civil War.

Lincoln is often praised for his work as a wartime leader who proved himself at balancing competing considerations and at getting rival groups to work together toward a common goal. Lincoln had to negotiate between Radical and Moderate Republican leaders, who were often far apart on the issues, while attempting to win support from War Democrats and loyalists in the seceding states. He personally directed the war effort, in close cooperation (1864-65) with General Ulysses S. Grant which in spring 1865 led to the surrender of all Confederate armies.

His leadership qualities were evident in his first diplomatic handling of the border slave states at the beginning of the fighting, in his defeat of a congressional attempt to reorganize his cabinet in 1862, in his many speeches and writings which helped mobilize and inspire the North, and in his defusing of the peace issue in the 1864 presidential campaign. Copperheads vehemently criticized him for violating the Constitution, overstepping the bounds of executive power, refusing to compromise on slavery, declaring martial law, suspending habeas corpus, ordering the arrest of 18,000 opponents including public officials and newspaper publishers, and killing hundreds of thousands of young men. Radical Republicans criticized him for going too slow in the abolition of slavery, and not being ruthless enough toward the conquered South.

Lincoln is most famous for his roles in preserving the Union and ending slavery in the United States with the Emancipation Proclamation and the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Historians have argued that Lincoln had a lasting influence on U.S. political and social institutions, importantly setting a precedent for greater centralization of powers in the federal government and the weakening of the powers of the individual state governments.

Lincoln spent most of his attention on military matters and politics but with his strong support his administration established the current system of national banks with the National Bank Act. He increased the tariff to raise revenue and encourage factories, imposed the first income tax, issued hundreds of millions of dollars of bonds and Greenbacks, encouraged immigration from Europe, built the transcontinental railroad, set up the Department of Agriculture, encouraged farm ownership with the Homestead Act of 1862, and set up the modern system of state universities with the Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act. During the war his Treasury department effectively controlled all cotton trade in the occupied South--the most dramatic incursion of federal controls on the economy. During his administration West Virginia and Nevada were admitted as states.

Lincoln is usually ranked as one of the greatest presidents. Because of his roles in destroying slavery, redefining national values, and saving the Union, his assassination made him a martyr to millions of Americans. However, others considered him an unconstitutional tyrant for declaring martial law, suspending civil liberties, habeas corpus, and the First Amendment, and ordering the arrest of thousands of public officials and newspaper publishers.

Early life

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, in a one-room log cabin on the 348 acre (1.4 km²) Sinking Spring Farm in the Southeast part of Hardin County, Kentucky, then considered the frontier (now part of LaRue Co., in Nolin Creek, three miles (5 km) south of Hodgenville), to Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks. Lincoln was named after his deceased grandfather, who was scalped in 1786 in an Indian raid. He had no middle name. Lincoln's parents were uneducated, illiterate farmers. When Lincoln became famous, reporters and storytellers often exaggerated the poverty and obscurity of his birth. However Lincoln's father Thomas was a respected and relatively affluent citizen of the Kentucky backcountry. He had purchased the Sinking Spring Farm in December 1808 for $200 cash and assumption of a debt. His parents belonged to a Baptist church that had pulled away from a larger church because they refused to support slavery. From a very young age, Lincoln was exposed to anti-slavery sentiment. However he never joined his parents' church, or any other church, and as a youth ridiculed religion.

Three years after purchasing the property, a prior land claim filed in Hardin Circuit Court forced the Lincolns to move. Thomas continued legal action until he lost the case in 1815. Legal expenses contributed to family difficulties. In 1811, they were able to lease 30 acres (0.1 km²) of a 230 acre (0.9 km²) farm on Knob Creek a few miles away, where they then moved. In a valley of the Rolling Fork River, this was some of the best farmland in the area. At this time, Lincoln's father was a respected community member and a successful farmer and carpenter. Lincoln's earliest recollections are from this farm. In 1815, another claimant sought to eject the family from the Knob Creek farm. Frustrated with litigation and lack of security provided by Kentucky courts, Thomas decided to move to Indiana, which had been surveyed by the federal government, making land titles more secure. It is possible that these episodes motivated Abraham to later learn surveying and become an attorney.

In 1816, when Lincoln was seven years old, he and his parents moved to Spencer County, Indiana, he would state "partly on account of slavery" and partly because of economic difficulties in Kentucky. In 1818, Lincoln's mother died of "milk sickness" at age thirty four, when Abe was nine. Soon afterwards, Lincoln's father remarried to Sarah Bush Johnston. Sarah Lincoln raised young Lincoln like one of her own children. Years later she compared Lincoln to her own son, saying "Both were good boys, but I must say — both now being dead that Abe was the best boy I ever saw or ever expect to see." (Lincoln, by David Herbert Donald, 1995)

In 1830, after more economic and land-title difficulties in Indiana, the family settled on government land on a site selected by Lincoln's father in Macon County, Illinois. The following winter was especially brutal, and the family nearly moved back to Indiana. When his father relocated the family to a nearby site the following year, the 22-year-old Lincoln struck out on his own, canoing down the Sangamon to Sangamon County, Illinois, in the village of New Salem. Later that year, hired by New Salem businessman Denton Offutt and accompanied by friends, he took goods from New Salem to New Orleans via flatboat on the Sangamon, Illinois and Mississippi rivers. While in New Orleans, he may have witnessed a slave auction that left an indelible impression on him for the rest of his life. Whether he actually witnessed a slave auction at that time or not, living in a country with a considerable slave presence, he probably saw similar atrocities from time to time.

His formal education consisted of perhaps 18 months of schooling from itinerant teachers. In effect he was self-educated, studying every book he could borrow. He mastered the Bible, Shakespeare, English history and American history, and developed a plain style that puzzled audiences more used to orotund oratory. He avoided hunting and fishing because he did not like killing animals even for food and, though unusually tall and strong, spent so much time reading that some neighbors thought he must be doing it to avoid strenuous manual labor. He was skilled with an axe—they called him the "rail splitter"—and a good wrestler.

Early career

Lincoln began his political career in 1832 at the age of 23 with a campaign for the Illinois General Assembly as a member of the Whig Party. The centerpiece of his platform was the undertaking of navigational improvements on the Sangamon River in the hopes of attracting steamboat traffic to the river, which would allow sparsely populated, poor areas along and near the river to grow and prosper. He served as a captain in a company of the Illinois militia drawn from New Salem during the Black Hawk War, although he never saw combat. He wrote after being elected by his peers that he had not had "any such success in life which gave him so much satisfaction."

He later tried and failed at several small-time business ventures. He held an Illinois state liquor license and sold whiskey. Finally, after coming across the second volume of Sir William Blackstone's four-volume Commentaries on the Laws of England, he taught himself the law, and was admitted to the Illinois Bar in 1837. That same year, he moved to Springfield, Illinois and began to practice law with Stephen T. Logan. He became one of the most respected and successful lawyers in the prairie state, and grew steadily more prosperous. Lincoln served four successive terms in the Illinois House of Representatives, as a representative from Sangamon County, beginning in 1834. He became a leader of the Whig party in the legislature. In 1837 he made his first protest against slavery in the Illinois House, stating that the institution was "founded on both injustice and bad policy."

Lincoln shared a bed with Joshua Fry Speed from 1837 to 1841 in Springfield. While many historians claim it was not uncommon in the mid-19th century for men to share a bed (just as two men today may share a house or an apartment), gay activist C. A. Tripp generated controversy with his 2005 book The Intimate World of Abraham Lincoln, which suggested their relationship may also have been sexual.

In 1841, Lincoln entered law practice with William Herndon, a fellow Whig. In 1856, both men joined the fledgling Republican Party. Following Lincoln's assassination, Herndon began collecting stories about Lincoln from those who knew him in central Illinois, eventually publishing a book, Herndon's Lincoln. Lincoln never joined an antislavery society and denied he supported the abolitionists. He married into a prominent slave-owning family from Kentucky, and allowed his children to spend time there surrounded by slaves. Several of his in-laws became Confederate officers. He greatly admired the science that flourished in New England, and was perhaps the only father in Illinois at the time to send his son, Robert Todd Lincoln, to elite eastern schools, Phillips Exeter Academy and Harvard College.

Marriage

On November 4, 1842, at the age of 33, Lincoln married Mary Todd. The couple had four sons.

- Robert Todd Lincoln: b. August 1, 1843, in Springfield, Illinois; d. July 26, 1926, in Manchester, Vermont.

- Edward Baker Lincoln: b. March 10, 1846, in Springfield, Illinois; d. February 1, 1850, in Springfield, Illinois.

- William Wallace Lincoln: b. December 21, 1850, in Springfield, Illinois; d. February 20, 1862, in Washington, D.C.

- Thomas (Tad) Lincoln: b. April 4, 1853, in Springfield, Illinois; d. July 16, 1871, in Chicago, Illinois.

Only Robert survived into adulthood. Of Robert's three children, only Jessie Lincoln had any children (two: Mary Lincoln Beckwith and Robert Todd Lincoln Beckwith). Neither Robert Beckwith nor Mary Beckwith had any children, so Abraham Lincoln's bloodline ended when Robert Beckwith (Lincoln's great-grandson) died on December 24, 1985.

Illinois politics

In 1846, Lincoln was elected to one term in the U.S. House of Representatives. A staunch Whig, Lincoln often referred to party leader Henry Clay as his political idol. As a freshman House member, Lincoln was not a particularly powerful or influential figure in Congress. He used his office as an opportunity to speak out against the war with Mexico, which he attributed to President Polk's desire for "military glory — that attractive rainbow, that rises in showers of blood."

Lincoln was a key early supporter of Zachary Taylor's candidacy for the 1848 Whig Presidential nomination. When Lincoln's term ended, the incoming Taylor administration offered him the governorship of remote Oregon Territory. Acceptance would end his career in the fast-growing state of Illinois, so he declined. Returning instead to Springfield, Illinois he turned most of his energies to making a living at the bar, which involved extensive travels on horseback from county to county.

Prairie lawyer

By the mid-1850s, Lincoln faced competing transportation interests — both the river barges and the railroads. In 1849, he received a patent related to buoying vessels. Lincoln represented the Alton & Sangamon Railroad in an 1851 dispute with one of its shareholders, James A. Barret. Barret had refused to pay the balance on his pledge to that corporation on the grounds that it had changed its originally planned route. Lincoln argued that as a matter of law a corporation is not bound by its original charter when that charter can be amended in the public interest, that the newer proposed Alton & Sangamon route was superior and less expensive, and that accordingly the corporation had a right to sue Mr. Barret for his delinquent payment. He won this case, and the decision by the Illinois Supreme Court was eventually cited by several other courts throughout the United States.

Another important example of Lincoln's skills as a railroad lawyer was a lawsuit over a tax exemption that the state granted to the Illinois Central Railroad. McLean County argued that the state had no authority to grant such an exemption, and it sought to impose taxes on the railroad notwithstanding. In January 1856, the Illinois Supreme Court delivered its opinion upholding the tax exemption, accepting Lincoln's arguments.

Lincoln's most notable criminal trial came in 1858 when he defended William "Duff" Armstrong, who was on trial for the murder of James Preston Metzker. The case is famous for Lincoln's use of judicial notice, a rare tactic at that time, to show an eyewitness had lied on the stand, claiming he witnessed the crime in the moonlight. Lincoln produced a Farmer's Almanac to show that the moon on that date was at such a low angle it could not have produced enough illumination to see anything clearly. Based upon this evidence, Armstrong was acquitted.

Republican politics 1854-1860

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which expressly repealed the limits on slavery's spread that had been part of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, drew Lincoln back into politics.

Illinois Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, the most powerful man in the Senate, proposed popular sovereignty as the solution to the slavery impasse, incorporating it into the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Douglas argued that in a democracy the people of a territory should decide whether to allow slavery or not, and not have a decision imposed on them by Congress.

It was a speech against Kansas-Nebraska, on October 16, 1854 in Peoria, that caused Lincoln to stand out among the other free soil orators of the day. He helped form the new Republican party, drawing on remnants of the old Whig, Free Soil, Liberty and Democratic parties. In a stirring campaign, the Republicans carried Illinois in 1854, and elected a senator. Lincoln was the obvious choice, but to keep party unity he allowed the election to go to his colleague Lyman Trumbull.

In 1857-58 Douglas broke with President Buchanan, leading to a terrific fight for control of the Democratic party. Some eastern Republicans even favored the reelection of Douglas in 1858, since he led the opposition to the administration's push for the Lecompton Constitution which would have admitted Kansas as a slave state. Accepting the Republican nomination for the Senate in 1858, Lincoln delivered a famous speech in which he stated, "A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved — I do not expect the house to fall — but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other." The speech created a lasting image of the danger of disunion due to slavery, and rallied Republicans across the north.

The 1858 campaign featured the Lincoln-Douglas debates, a nationally noticed discussion on the issues that threatened to split the nation in two. Lincoln forced Douglas to propose his Freeport Doctrine, which lost him further support among slave-holders and speeded the division of the Democratic Party. Though the Republican legislative candidates won more popular votes, the Democrats won more seats and the legislature reelected Douglas to the Senate. Nevertheless, Lincoln's eloquence transformed him into a national political star.

During the debates of 1858 the issue of race was often discussed. During a time period when racial egalitarianism was considered politically incorrect, Stephen Douglas would inform the crowds, “If you desire negro citizenship…if you desire them to vote on an equality with yourselves… then support Mr. Lincoln and the Black Republican party, who are in favor of the citizenship of the negro.” (Official Records of Debate) On the defensive Lincoln countered that he was “not in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races.” (Official Records of Debate) Historians generally remained mixed on what Lincoln’s actual views were on race. However, many tend to doubt that the highly political nature of these debates offer reliable evidence about his personal views. (Team of Rivals, by Doris Kearns Goodwin, 2005) (Lincoln: In Text and Context, by Donald Fehrenbacher, 1987) As Fredrick Douglass observed, “ the first great man that I talked with in the United States freely who in no single instance reminded me of the difference between himself and myself, of the difference of color.” (Life and Times of Fredrick Douglass, by Fredrick Douglass, 1895)

Lincoln's opposition to slavery was opposition to the Slave Power, and he was not an abolitionist in 1858. But the Civil War changed everything, and changed Lincoln's beliefs in race relations as well.

Election of 1860

Entering the presidential nomination process as a distinct underdog, Lincoln was eventually chosen as the Republican candidate for the 1860 election for several reasons. His expressed views on slavery were seen as more moderate than rivals William H. Seward and Salmon Chase. His "western" origins also appealed to the newer states. Other contenders, especially those with more governmental experience, had acquired enemies within the party, specifically Seward, who had run afoul of newspaperman Horace Greeley. During the campaign, Lincoln was dubbed "The Rail Splitter" by Republicans to emphasize the power of "free labor," whereby a common farm boy could work his way to the top by his own efforts.

On November 6, 1860, Lincoln was elected the 16th President of the United States, beating Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, John C. Breckenridge of the Southern Democrats, and John C. Bell of the new Constitutional Union Party. Lincoln was the first Republican president. He won entirely on the strength of his support in the North: he was not even on the ballot in nine states in the South — and won only 2 of 996 counties there. Lincoln gained 1,865,908 votes (39.9% of the total,) for 180 electoral votes, Douglas 1,380,202 (29.5%) for 12 electoral votes, Breckenridge 848,019 (18.1%) for 72 electoral votes, and Bell 590,901 (12.5%) for 39 electoral votes. There were fusion tickets in some states, but even if his opponents had combined in every state, Lincoln had a majority vote in all but two of the states in which he won the electoral votes, and would still have won the electoral college and the election.

Secession winter 1860-61

As Lincoln's election became more and more probable, secessionists made it clear that their states would leave the Union. South Carolina took the lead followed by six other cotton-growing states: Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. The upper South (Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, Missouri, and Arkansas) listened to and rejected the secessionist appeal. They decided to stay in the Union, though warning Lincoln they would not support an invasion through their territory. The seven Confederate states seceded before Lincoln took office, declaring themselves an entirely new nation, the Confederate States of America. President Buchanan and president-elect Lincoln refused to recognize the Confederacy.

President-elect Lincoln survived an assassination threat in Baltimore, and on February 23, 1861 arrived in disguise in Washington. At Lincoln's inauguration on March 4, 1861, the Turners formed Lincoln's bodyguard; and a sizable garrison of federal troops was also present, ready to protect the capital from Confederate invasion or insurrection from Confederates in the capital city.

In his First Inaugural Address, Lincoln declared, "I hold that in contemplation of universal law and of the Constitution the Union of these States is perpetual. Perpetuity is implied, if not expressed, in the fundamental law of all national governments", arguing further that the purpose of the United States Constitution was "to form a more perfect union" than the Articles of Confederation which were explicitly perpetual, and thus the Constitution too was perpetual. He asked rhetorically that even were the Constitution a simple contract, would it not require the agreement of all parties to rescind it?

Also in his inaugural address, in a final attempt to unite the Union and prevent the looming war, Lincoln supported the proposed Corwin Amendment to the constitution, of which he had been a driving force. It would have explicitly protected slavery in those states in which it already existed, and had already passed both houses. Lincoln adamantly opposed the Crittenden Compromise, however, which would have permitted slavery in the territories, renewing the boundary set by the Missouri Compromise and extending it to California. Despite support for this compromise among some Republicans, Lincoln declared that were the Crittenden Compromise accepted, it "would amount to a perpetual covenant of war against every people, tribe, and state owning a foot of land between here and Tierra del Fuego."

Because opposition to slavery expansion was the key issue uniting the Republican Party at the time, Lincoln is sometimes criticized for putting politics ahead of the national interest in refusing any compromise allowing the expansion of slavery. Supporters of Lincoln, however, point out that he did not oppose slavery because he was a Republican, but became a Republican because of his opposition to the expansion of slavery, that he opposed several other Republicans who were in favor of compromise, and that he clearly thought his course of action was in the national interest. By the time Lincoln took office the Confederacy was an established fact and not a single leader of that country ever proposed rejoining the Union on any terms. No compromise was found because no compromise was possible. Lincoln perhaps could have allowed the southern states to secede, and some Republicans recommended that. However conservative Democratic nationalists, such as Jeremiah S. Black, Joseph Holt, and Edwin M. Stanton had taken control of Buchanan's cabinet around January 1, 1861, and refused to accept secession. Lincoln, and nearly all Republican leaders, adopted this nationalistic position by March, 1861: the Union could not be broken.

War begins: 1861-1862

Main article: American Civil WarAfter Union troops at Fort Sumter were fired on and forced to surrender in April, Lincoln called on governors of every state to send 75,000 troops to recapture forts, protect the capital, and "preserve the Union," which in his view still existed intact despite the actions of the seceding states. Virginia, which had repeatedly warned Lincoln it would not allow an invasion of its territory or join an attack on another state, then seceded, along with North Carolina, Tennessee and Arkansas.

The slave states of Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware did not secede, and Lincoln urgently negotiated with state leaders there, promising not to interfere with slavery in loyal states.

Emancipation Proclamation

Congress in July 1862 moved to free the slaves by passing the Second Confiscation Act. It provided:

- That if any person shall hereafter incite, set on foot, assist, or engage in any rebellion or insurrection against the authority of the United States, or the laws thereof, or shall give aid or comfort thereto, or shall engage in, or give aid and comfort to, any such existing rebellion or insurrection, and be convicted thereof, such person shall be punished by imprisonment for a period not exceeding ten years, or by a fine not exceeding ten thousand dollars, and by the liberation of all his slaves, if any he have; or by both of said punishments, at the discretion of the court.

- ....

- SEC. 9. And be it further enacted, That all slaves of persons who shall hereafter be engaged in rebellion against the government of the United States, or who shall in any way give aid or comfort thereto, escaping from such persons and taking refuge within the lines of the army; and all slaves captured from such persons or deserted by them and coming under the control of the government of the United States; and all slaves of such person found on being within any place occupied by rebel forces and afterwards occupied by the forces of the United States, shall be deemed captives of war, and shall be forever free of their servitude, and not again held as slaves.

Thus everyone who 60 days after July 17, 1862 supported the rebellion was to be punished by having all their slaves freed. The goal was to weaken the rebellion, which was led and controlled by slave owners. This did not abolish the legal institution of slavery (the XIII Amendment did that), but it shows Lincoln had the support of (and was even somewhat pushed by) Congress in liberating the slaves owned by rebels. Lincoln implemented the new law by his "Emancipation Proclamation."

Lincoln is well known for ending slavery in the United States and he personally opposed slavery as a profound moral evil not in accord with the principle of equality asserted in the Declaration of Independence. Yet, Lincoln's views of the role of the federal government on the subject of slavery are more complicated. Before the Confederate states seceded, Lincoln had campaigned against the expansion of slavery into the territories, where Congress did have authority. However, he maintained that the federal government could not constitutionally bar slavery in states where it already existed. During his presidency, Lincoln made it clear that the North was fighting the war to preserve the Union, not to abolish slavery. Freeing the slaves was a war measure to weaken the rebellion by destroying the economic base of its leadership class. Lincoln was criticized both at home and abroad for his refusal to take a stand for the complete abolition of slavery. On August 22, 1862, a few weeks before signing the Proclamation, and after it had already been drafted, Lincoln responded by letter to an editorial by Horace Greeley of the New York Tribune which had urged abolition:

- I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored; the nearer the Union will be "the Union as it was." If there be those who would not save the Union, unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union. I shall do less whenever I shall believe what I am doing hurts the cause, and I shall do more whenever I shall believe doing more will help the cause. I shall try to correct errors when shown to be errors; and I shall adopt new views so fast as they shall appear to be true views.

- I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty; and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men everywhere could be free.

With the Emancipation Proclamation issued in two parts on September 22, 1862 and January 1, 1863, Lincoln made the abolition of slavery a goal of the war. Lincoln addresses the issue of his consistency (or lack thereof) between his earlier position and his later position on emancipation in an 1864 letter to Albert G. Hodges

Lincoln is often credited with freeing enslaved African Americans with the Emancipation Proclamation. However, border states that still allowed slavery but were under Union control were exempt from the emancipation because they were not covered under any war measures. The proclamation on its first day, January 1, 1863, freed only a few escaped slaves, but as Union armies advanced south more and more slaves were liberated until hundreds of thousands were freed (exactly how many is unknown). Lincoln signed the Proclamation as a wartime measure, insisting that only the outbreak of war gave constitutional power to the President to free slaves in states where it already existed. He later said: "I never, in my life, felt more certain that I was doing right, than I do in signing this paper." The proclamation made abolishing slavery in the rebel states an official war goal and it became the impetus for the enactment of the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution which abolished slavery; Lincoln was one of the main promoters of that amendment.

Although some Northern conservatives recoiled at the notion that the war was now being fought for the slaves instead of for preserving the Union, in the end the Emancipation Proclamation did much to help the Northern cause politically. Lincoln's strong abolitionist stand finally convinced the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and other foreign countries that they could not support the Confederate States of America. This move remains one of the great seizures of private property by the federal government, restoring the ownership of the blacks to themselves,

Lincoln had for some time been working on plans to set up colonies in Africa and South America for the nearly 4 million newly freed slaves. He remarked upon colonization favorably in the Emancipation Proclamation, but all attempts at such a massive undertaking failed.

Important domestic measures of Lincoln's first term

Lincoln believed in the Whig theory of the presidency, which left Congress to write the laws while he signed them, vetoing only bills that threatened his war powers. Thus he signed the Homestead Act in 1862, making available millions of acres of government-held land in the west for purchase at very low cost. The Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act, also signed in 1862, provided government grants for agricultural universities in each state. Lincoln also signed the Pacific Railway Acts of 1862 and 1864, which granted federal support to the construction of the United States' first transcontinental railroad, which was completed in 1869. The most important legislation involved money matters, including the first income tax and higher tariffs. Most important was the creation of the system of national banks by the National Banking Acts of 1863, 1864 and 1865 which allowed the creation of a strong national financial system.

Lincoln sent a senior general to put down the "Sioux Uprising" of August 1862 in Minnesota. Presented with 303 death warrants for convicted Santee Dakota who had massacred innocent farmers, Lincoln affirmed 39 of these for execution (one was later reprieved).

1864 election and second inauguration

After Union victories at Gettysburg, Vicksburg and Chattanooga in 1863, many in the North believed that victory was soon to come after Lincoln appointed U.S. Grant General-in-Chief on March 12, 1864. Although no president since Andrew Jackson had been elected to a second term (and none since Van Buren had been re-nominated), Lincoln's re-election was considered a certainty.

However, when the spring campaigns, east and west, all turned into bloody stalemates, Northern morale dipped and Lincoln seemed less likely to be re-nominated. Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase strongly desired the Republican nomination and was working hard to win it, while John Fremont was nominated by a breakoff group of radical Republicans, potentially taking away crucial votes in the November elections.

Fearing he might lose the election, Lincoln wrote out and signed the following pledge, but did not show it to his cabinet, asking them each to sign the sealed envelope. Lincoln wrote:

- This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so co-operate with the President elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he can not possibly save it afterwards.

The Democrats, hoping to make setbacks in the war a top campaign issue, waited until late summer to nominate a candidate. Their platform was heavily influenced by the Peace wing of the party, calling the war a "failure," but their candidate, former General George McClellan, was a War Democrat, determined to prosecute the war until the Union was restored, although willing to compromise on all other issues, including slavery.

McClellan's candidacy was soon undercut as on September 1, just two days after the convention, Atlanta was abandoned by the Confederate army. Coming on the heels of David Farragut's capture of Mobile Bay and followed by Phil Sheridan's crushing victory over Jubal Early's army at Cedar Creek, it was now apparent that the tide had turned in favor of the Union and that Lincoln may be reelected despite the costs of the war.

Still, Lincoln believed that he would win the electoral vote by only a slim margin, failing to give him the mandate he'd need if he was to push his lenient reconstruction plan. To his surprise, Lincoln ended up winning all but two states, capturing 212 of 233 electoral votes.

After Lincoln's election, on March 4, 1865, he delivered his second inaugural address, which was his favorite of all his speeches. At this time, a victory over the rebels was within sight, slavery had effectively ended, and Lincoln was looking to the future.

- Fondly do we hope--fervently do we pray--that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said "the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether"

- With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation's wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan--to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.

Civil War and reconstruction

Conducting the war effort

The war was a source of constant frustration for the president, and it occupied nearly all of his time. Lincoln had a contentious relationship with General George B. McClellan, who became general-in-chief of all the Union armies in the wake of the embarrassing Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run and after the retirement of Winfield Scott in late 1861. Lincoln wished to take an active part in planning the war strategy despite his inexperience in military affairs. Lincoln's strategic priorities were two-fold: first, to ensure that Washington, D.C., was well-defended; and second, to conduct an aggressive war effort in hopes of ending the war quickly and appeasing the Northern public and press, who pushed for an offensive war. McClellan, a youthful West Point graduate and railroad executive called back to military service, took a more cautious approach. McClellan took several months to plan and execute his Peninsula Campaign, which involved capturing Richmond by moving the Army of the Potomac by boat to the peninsula between the James and York Rivers. McClellan's delay irritated Lincoln, as did McClellan's insistence that no troops were needed to defend Washington, D.C. Lincoln insisted on holding some of McClellan's troops to defend the capital, a decision McClellan blamed for the ultimate failure of his Peninsula Campaign.

McClellan, a lifelong Democrat who was temperamentally conservative, was relieved as general-in-chief after releasing his Harrison's Landing Letter, where he offered unsolicited political advice to Lincoln urging caution in the war effort. McClellan's letter incensed Radical Republicans, who successfully pressured Lincoln to appoint fellow Republican John Pope as head of the new Army of Virginia. Pope complied with Lincoln's strategic desire for the Union to move towards Richmond from the north, thus guarding Washington, D.C. However, Pope was soundly defeated at the Second Battle of Bull Run during the summer of 1862, forcing the Army of the Potomac back into the defenses of Washington for a second time. Pope was sent to Minnesota to fight the Sioux.

Panicked by Confederate General Robert E. Lee's invasion of Maryland, Lincoln restored McClellan to command of all forces around Washington in time for the Battle of Antietam in September 1862. It was the Union victory in that battle that allowed Lincoln to release his Emancipation Proclamation. Lincoln relieved McClellan of command shortly after the 1862 midterm elections and appointed Republican Ambrose Burnside to head the Army of the Potomac, who promised to follow through on Lincoln's strategic vision for an aggressive offensive against Lee and Richmond. After Burnside was stunningly defeated at Fredericksburg, Joseph Hooker was given command, despite his idle talk about becoming a military strong man. Hooker was routed by Lee at Chancellorsville in May 1863 and also relieved of command.

After the Union victory at Gettysburg, Meade's failure to pursue Lee, and months of inactivity for the Army of the Potomac, Lincoln decided to bring in a western general: General Ulysses S. Grant. He had a solid string of victories in the Western Theater, including Vicksburg and Chattanooga. Earlier, reacting to criticism of Grant, Lincoln was quoted as saying, "I cannot spare this man. He fights." Grant waged his bloody Overland Campaign in 1864, using a strategy of a war of attrition, characterized by high Union losses at battles such as the Wilderness and Cold Harbor, but by proportionately higher losses in the Confederate army. Grant's aggressive campaign would eventually bottle up Lee in the Siege of Petersburg and result in the Union taking Richmond and bringing the war to a close in the spring of 1865.

Lincoln authorized Grant to use a scorched earth approach to destroy the South's morale and economic ability to continue the war. This allowed Generals William Tecumseh Sherman and Philip Sheridan to destroy farms and towns in the Shenandoah Valley, Georgia, and South Carolina. The damage in Sherman's March to the Sea through Georgia totaled in excess of $100 million.

Lincoln had a star-crossed record as a military leader, possessing a keen understanding of strategic points (such as the Mississippi River and the fortress city of Vicksburg) and the importance of defeating the enemy's army, rather than simply capturing cities. However, he had little success in his efforts to motivate his generals to adopt his strategies. Eventually, he found in Grant a man who shared his vision of the war and was able to bring that vision to reality with his relentless pursuit of coordinated offensives in multiple theaters of war.

Lincoln, perhaps reflecting his lack of military experience, developed a keen curiosity with military campaigning during the war. He spent hours at the War Department telegraph office, reading dispatches from his generals through many a night. He frequently visited battle sites and seemed fascinated by watching scenes of war. During Jubal A. Early's raid into Washington, D.C., in 1864, Lincoln had to be told to duck his head to avoid being shot while observing the scenes of battle.

Homefront

Lincoln was more successful in giving the war meaning to Northern civilians through his oratorical skills. Despite his meager education and “backwoods” upbringing, Lincoln possessed an extraordinary command of the English language, as evidenced by the Gettysburg Address, a speech dedicating a cemetery of Union soldiers from the Battle of Gettysburg that he delivered on November 19, 1863. While the featured speaker, orator Edward Everett, spoke for two hours, Lincoln's few choice words resonated across the nation and across history, defying Lincoln's own prediction that "the world will little note, nor long remember what we say here." Lincoln's second inaugural address is also greatly admired and often quoted. In these speeches, Lincoln articulated better than any of his contemporaries the rationale behind the Union effort.

During the Civil War, Lincoln exercised powers no previous president had wielded; he proclaimed a blockade, suspended the writ of habeas corpus, spent money without congressional authorization, and imprisoned thousands of accused Confederate sympathizers without trial. There is a fragment of uncorraborated evidence that Lincoln made contingency plans to arrest Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney, though the allegation remains unresolved and controversial (see the Taney Arrest Warrant controversy).

The long war and the issue of emancipation appeared to be severely hampering his prospects and pessimists warned that defeat appeared likely. Lincoln ran under the Union party banner, composed of War Democrats and Republicans. General Grant was facing severe criticism for his conduct of the bloody Overland Campaign that summer and the seemingly endless Siege of Petersburg. However, the Union capture of the key railroad center of Atlanta by Sherman's forces in September changed the situation dramatically and Lincoln was reelected.

Reconstruction

The reconstruction of the Union weighed heavy on the President's mind throughout the war effort. He was determined to take a course that would not permanently alienate the former Confederate states, and throughout the war Lincoln urged speedy elections under generous terms in areas behind Union lines. This irritated congressional Republicans, who urged a more stringent Reconstruction policy. One of Lincoln's few vetoes during his term was of the Wade-Davis Bill, an effort by congressional Republicans to impose harsher Reconstruction terms on the Confederate areas. Republicans in Congress retaliated by refusing to seat representatives elected from Louisiana, Arkansas, and Tennessee during the war under Lincoln's generous terms.

"Let 'em up easy," he told his assembled military leaders Gen. Ulysses S. Grant (a future president), Gen. William T. Sherman and Adm. David Dixon Porter in an 1865 meeting on the steamer River Queen. When Richmond, the Confederate capital, was at long last captured, Lincoln went there to make a public gesture of sitting at Jefferson Davis's own desk, symbolically saying to the nation that the President of the United States held authority over the entire land. He was greeted at the city as a conquering hero by freed slaves, whose sentiments were epitomized by one admirer's quote, "I know I am free for I have seen the face of Father Abraham and have felt him."

On April 9, 1865, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House in Virginia. This left only Joseph Johnston's forces in the East to deal with. Weeks later Johnston would defy Jefferson Davis and surrender his forces to Sherman. Of course, Lincoln would not survive to see the surrender of all Confederate forces; just five days after Lee surrendered, Lincoln was assassinated. He was the first President to be assassinated, and the third to die in office.

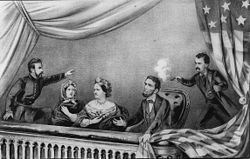

Assassination

Lincoln had met frequently with Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant as the war drew to a close. The two men planned matters of reconstruction, and it was evident to all that they held each other in high regard. During their last meeting, on April 14, 1865 (Good Friday), Lincoln invited Grant to a social engagement that evening. Grant declined (Grant's wife, Julia Dent Grant, is said to have strongly disliked Mary Todd Lincoln). The President's eldest son, Robert Todd Lincoln, also turned down the invitation.

John Wilkes Booth, a well-known actor and Southern sympathizer from Maryland, heard that the president and Mrs. Lincoln, along with the Grants, would be attending Ford's Theatre. Having failed in a plot to kidnap Lincoln earlier, Booth informed his co-conspirators of his intention to kill Lincoln. Others were assigned to assassinate Vice-President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William Seward.

Without his main bodyguard Ward Hill Lamon, to whom he related his famous dream of his own assassination, the Lincolns left to attend the play at Ford's Theater. The play, Our American Cousin. As a lone bodyguard wandered, and Lincoln sat in his state box in the balcony, Booth crept up behind the President's box and waited for the funniest line of the play, hoping the laughter would cover the gunshot noise. On stage, actor Harry Hawk said the last words Lincoln would ever hear "Well, I guess I know enough to turn you inside out, old gal—you sockdologizing old man-trap...". When the laughter came Booth jumped into the box the president was in and aimed a single-shot, round-slug .44 caliber Deringer at his head, firing at point-blank range. The bullet entered behind Lincoln's left ear and lodged behind his right eyeball. Major Henry Rathbone, who was present in the Presidential Box, momentarily grappled with Booth. Booth then shouted "Sic semper tyrannis!" (Latin: "Thus always to tyrants," the state motto of Virginia; some accounts say he added "The South is avenged!") and jumped from the balcony to the stage below, breaking his leg. Despite his injury, Booth managed to limp to his horse and make his escape.

An army surgeon, Dr. Charles Leale quickly assessed the wound as mortal. The President was taken across the street from the theater to the Petersen House, where he lay in a coma for nine hours before he expired. Several physicians attended Lincoln, including U.S. Army Surgeon General Joseph K. Barnes of the Army Medical Museum. Using a probe, Barnes located some fragments of Lincoln's skull and the ball lodged 6 inches inside his brain. Lincoln, who never regained consciousness, was officially pronounced dead at 7:22 A.M. the next morning, April 15, 1865. Upon his death, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton lamented "now he belongs to the ages." After Lincoln's body was returned to the White House, his body was prepared for his "lying in state" in the East Room.

The Army Medical Museum, now named the National Museum of Health and Medicine, has retained in its collection since the time of Lincoln's death, several artifacts relating to the assassination. Currently on display in the museum are the bullet that was fired from the Deringer pistol, ending Lincoln's life, the probe used by Barnes, pieces of his skull and hair and the surgeon's cuff, stained with Lincoln's blood. The museum can be found at www.hmhm.washingtondc.museum

Lincoln's body was carried by train in a grand funeral procession through several states on its way back to Illinois. The nation mourned a man whom many viewed as the savior of the United States. He was buried in Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, where a 177 foot (54 m) tall granite tomb surmounted with several bronze statues of Lincoln was constructed by 1874. To prevent repeated attempts to steal Lincoln's body and hold it for ransom, Robert Todd Lincoln had Lincoln exhumed and reinterred in concrete several feet thick in 1901.

Further information: ]Presidential appointments

Administration and cabinet

Lincoln was known for appointing his political rivals to high positions in his Cabinet to keep in line all factions of his party--and to let them battle each other and not combine against Lincoln. Historians agree that except for Cameron, it was a highly effective group.

| Office | Name | Term |

|---|---|---|

| President | Abraham Lincoln | 1861–1865 |

| Vice President | Hannibal Hamlin | 1861–1865 |

| Andrew Johnson | 1865 | |

| Secretary of State | William H. Seward | 1861–1865 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Salmon P. Chase | 1861–1864 |

| William P. Fessenden | 1864–1865 | |

| Hugh McCulloch | 1865 | |

| Secretary of War | Simon Cameron | 1861–1862 |

| Edwin M. Stanton | 1862–1865 | |

| Attorney General | Edward Bates | 1861–1864 |

| James Speed | 1864–1865 | |

| Postmaster General | Horatio King | 1861 |

| Montgomery Blair | 1861–1864 | |

| William Dennison | 1864–1865 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Gideon Welles | 1861–1865 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Caleb B. Smith | 1861–1863 |

| John P. Usher | 1863–1865 |

Supreme Court

Lincoln appointed the following Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- Noah Haynes Swayne - 1862

- Samuel Freeman Miller - 1862

- David Davis - 1862

- Stephen Johnson Field - 1863

- Salmon P. Chase - Chief Justice - 1864

Major presidential acts

Involvement as President-elect

Enacted as President

- Signed Revenue Act of 1861

- Signed Homestead Act

- Signed Morill Land-Grant College Act

- Signed Internal Revenue Act of 1862

- Signed Pacific Railway Acts of 1862 and 1864

- Established Department of Agriculture (1862)

- Signed National Banking Act of 1863

- Signed Internal Revenue Act of 1864

States admitted to the Union

- West Virginia – 1863

- Nevada – 1864

Legacy and memorials

Lincoln's death made the President a martyr to many. Today he is perhaps America's second most famous and beloved President after George Washington. Repeated polls of historians have ranked Lincoln as among the greatest presidents in U.S. history. Among contemporary admirers, Lincoln is usually seen as a figure who personifies classical values of honesty, integrity, as well as respect for individual and minority rights, and human freedom in general. Many American organizations of all purposes and agendas continue to cite his name and image, with interests ranging from the gay rights group Log Cabin Republicans to the insurance corporation Lincoln Financial. The Lincoln automobile is also named after him.

Over the years Lincoln has been memorialized in many city names, notably the capital of Nebraska; with the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. (pictured, right); on the U.S. $5 bill and the 1 cent coin (Illinois is the primary opponent to the removal of the penny from circulation); and as part of the Mount Rushmore National Memorial. Lincoln's Tomb, Lincoln Home National Historic Site in Springfield, New Salem, Illinois (a reconstruction of Lincoln's early adult hometown), Ford's Theater and Petersen House are all preserved as museums. The state nickname for Illinois is Land of Lincoln.

Counties in 18 U.S. states (Arkansas, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Dakota, Tennessee, West Virginia, Washington, Wisconsin, and Wyoming) are named after Lincoln.

On February 12, 1892, Abraham Lincoln's birthday was declared to be a federal holiday in the United States, although in 1971 it was combined with Washington's birthday in the form of President's Day. February 12 is still observed as a separate legal holiday in many states, including Illinois.

Lincoln's birthplace and family home are national historic memorials: Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site in Hodgenville, Kentucky and Lincoln Home National Historic Site in Springfield, Illinois. The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, opened in 2005 in Springfield as a major tourist attraction with state-of-the-art exhibits. The Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery is located in Elwood, Illinois.

Statues of Lincoln can be found in other countries. In Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, Mexico, is a 13-foot high bronze statue, a gift from the United States, dedicated in 1966 by President Lyndon B. Johnson. The U.S. received a statue of Benito Juárez in exchange, which is in Washington, D.C. Juárez and Lincoln exchanged friendly letters, and Mexico remembers Lincoln's opposition to the Mexican-American War. There is also a statue in Tijuana, Mexico, showing Lincoln standing and destroying the chains of slavery. There are at least three statues of Lincoln in the United Kingdom—one in London by Augustus St. Gaudens, one in Manchester by George Grey Barnard and another in Edinburgh by George Bissell.

The ballistic missile submarine Abraham Lincoln (SSBN-602) and the aircraft carrier Abraham Lincoln (CVN-72) were named in his honor. Also, the Liberty ship, SS Nancy Hanks was named to honor his mother.

In a recent public vote entitled "The Greatest American," Lincoln placed second (placing first was Ronald Reagan).

Lincoln in popular culture

Further information: Lincoln in popular cultureTrivia

- Lincoln stood 6'3 3/4" (192.4 cm) tall (not including his hat) and thus was the tallest president in U.S. history, just edging out Lyndon Johnson at 6'3 1/2" (191.8 cm).

- He was born on the same day as Charles Darwin.

- The last surviving self-described witness to Lincoln's assassination was Samuel J. Seymour (~1860–April 14, 1956), who appeared two months before his death at age 96 on the CBS-TV quiz show I've Got a Secret. He said that as a five-year-old he had thought at first that he, himself, had been shot because his nurse, trying to fix a torn place in his blouse, stuck him with a pin at the moment of the gun's discharge.

- According to legend, Lincoln was referred to as "two-faced" by his opponent in the 1858 Senate election, Stephen Douglas. Upon hearing about this Lincoln jokingly replied, "If I had another face to wear, do you really think I would be wearing this one?"

- According to legend, Lincoln also said, as a young man, on his appearance one day when looking in the mirror: "It's a fact, Abe! You are the ugliest man in the world. If ever I see a man uglier than you, I'm going to shoot him on the spot!" It would no doubt, he thought, be an act of mercy.

- Based on written descriptions of Lincoln, including the observations that he was much taller than most men of his day and had long limbs, an abnormally-shaped chest, and loose or lax joints, it has been conjectured since the 1960s that Lincoln may have suffered from Marfan syndrome.

- Lincoln was known to have a case of depression. During his time in New Salem, Illinois, his fiancee died, and that triggered his depression. His close friends watched over him to make sure he did not commit suicide. He also suffered from nightmares during his term in the White House. His depression got so severe, he had to hold a cabinet meeting from his bed.

- He once mentioned one of his haunting nightmares to his friend. Lincoln mentioned that he was standing in a mourning crowd surrounding a train, and when he asked a grieving woman what had happened, she replied, "The President has been shot, and he has died."

- Lincoln is the only American president to hold a patent. The patent is for a device that lifts boats over shoals.

See also

- Origins of the American Civil War

- American System, Lincoln's economic beliefs.

- Lincoln-Kennedy coincidences

- List of U.S. Presidential religious affiliations

- Movies: D.W. Griffith's 'Abraham Lincoln', The Dramatic Life of Abraham Lincoln

- Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum

References

Biographies

- Lincoln by David Herbert Donald (1999) ISBN 068482535X, very well reviewed by scholars; Donald has won two Pulitzer prizes for biography

- Abraham Lincoln and Civil War America: A Biography by William E. Gienapp ISBN 0195150996 (2002), short

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln by Doris Kearns Goodwin ISBN 0684824906 (2005). reviewers report it is very well written

- Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President by Allen C. Guelzo ISBN 0802838723 (1999)

- Abraham Lincoln: a History (1890) by John Hay & John George Nicolay; online at Volume 1 and Volume 2 10 volumes in all; written by Lincoln's top aides

- The Real Abraham Lincoln by Reinhard H Luthin (1960), well regarded by reviewers

- The Abraham Lincoln Encyclopedia by Mark E. Neely (1984), detailed articles on many men and movements associated with AL

- The Last Best Hope of Earth: Abraham Lincoln and the Promise of America by Mark E. Neely (1993), Pulitzer prize winning author

- With Malice Toward None: The Life of Abraham Lincoln by Stephen B. Oates (1994).

- Lincoln the President by James G. Randall (4 vol., 1945–55; reprint 2000.) by prize winning scholar

- Mr. Lincoln excerpts ed. by Richard N. Current (1957)

- Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years (2 vol 1926); The War Years (4 vol 1939) biography by Carl Sandburg. Pulitzer Prize winner by famous poet

- Abraham Lincoln: A Biography by Benjamin P. Thomas; (1952)

Specialty topics

- Baker, Jean H. Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biography (1987)

- Belz, Herman. Abraham Lincoln, Constitutionalism, and Equal Rights in the Civil War Era (1998)

- Boritt, Gabor S. Lincoln and the Economics of the American Dream (1994). Lincoln's economic theory and policies

- Boritt, Gabor S. Lincoln the War President (1994).

- Boritt, Gabor S., ed. The Historian's Lincoln. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988, historiography

- Bruce, Robert V. Lincoln and the Tools of War (1956) on weapons development during the war

- Donald, David Herbert. Lincoln Reconsidered: Essays on the Civil War Era (1960).

- Foner, Eric. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War (1970) intellectual history of different prewar faction's in AL's party

- Harris, William C. With Charity for All: Lincoln and the Restoration of the Union (1997). AL's plans for Reconstruction

- Hendrick, Burton J. Lincoln's War Cabinet (1946)

- Hofstadter, Richard. The American Political Tradition: And the Men Who Made It (1948) ch 5: "Abraham Lincoln and the Self-MAde Myth".

- Holzer, Harold. Lincoln at Cooper Union: The Speech That Made Abraham Lincoln President (2004).

- McPherson, James M. Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution (1992)

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (1988). Pulitzer Prize winner surveys all aspects of the war

- Morgenthau, Hans J., and David Hein. Essays on Lincoln's Faith and Politics. Lanham, MD: University Press of America for the White Burkett Miller Center of Public Affairs at the University of Virginia, 1983.

- Neely, Mark E. The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties (1992). Pulitzer Prize winner.

- Philip S. Paludan The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln (1994), reviewers call it the most thorough treatment of AL's administration

- Lincoln in American Memory by Merrill D. Peterson, (1994). how Lincoln was remembered after 1865

- Randall, James G. Lincoln the Liberal Statesman (1947).

- Richardson, Heather Cox. The Greatest Nation of the Earth: Republican Economic Policies during the Civil War (1997)

- Shenk, Joshua Wolf. Lincoln's Melancholy: How Depression Challenged a President and Fueled His Greatness (2005). Named one of the best books of 2005 by The Washington Post, The New York Times, and The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. *Lincoln by Gore Vidal ISBN 0375708766, a novel.

- Lincoln and His Generals by T. Harry Williams (1967).

- Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words That Remade America by Garry Wills ISBN 0671867423

- Honor's Voice: The Transformation of Abraham Lincoln by Douglas L. Wilson (1999).

Lincoln in art and popular culture

- DiLorenzo, Thomas (2002). The Real Lincoln. ISBN 0761526463.

- Lauriston, Bullard. F. (1952). Lincoln in Marble and Bronze. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

- Mead, Fanklin B. (1932). Heroic Statues in Bronze of Abraham Lincoln: Introducing The Hoosier Youth by Paul Manship. Fort Wayne, Indiana: The Lincoln National Life Foundation.

- Moffatt, Frederick C. (1998). Errant Bronzes: George Grey Barnard's Statues of Abraham Lincoln. Newark, DE: University of Deleware Press.

- Murry, Freeman Henry Morris (1972) . Emancipation and the Freed in American Sculpture. Freeport, NY: Books For Libraries Press, the Black Heritage Library Collection.

- Petz, Weldon (1987). Michigan's Monumental Tributes to Abraham Lincoln. Historical Society of Michigan.

- Redway, Maurine Whorton (1957). Marks of Lincoln on Our Land. New York: Hastings House, Publishers.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Savage, Kirk (1997). Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race War and Monument in Nineteenth Century America. Princeton New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Tice, George (1984). Lincoln. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Primary sources

- Basler, Roy P. ed. (1953–55). Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. 9 vols. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Univ. Press.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Basler, Roy P. ed. (1946). Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Lincoln, Abraham (1989). Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (2 vol Library of America edition ed.).

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Lincoln, Abraham (2000). ed by Philip Van Doren Stern (ed.). The Life and Writings of Abraham Lincoln. Modern Library Classics.

External links

- United States Congress. "Abraham Lincoln (id: L000313)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- White House Biography

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress (1850-1865)

- The Controversial photograph of Lincoln in death

- The Lincoln Institute

- Abraham Lincoln in United States Census Records

- Especially for Students: An Overview of Abraham Lincoln's Life

- Mr. Lincoln's Virtual Library

- Speeches and Quotes by Abraham Lincoln

- Poetry written by Abraham Lincoln

- Lincoln Memorial Tour - My Big Adventure (33 Images)

- Abraham Lincoln Research Site

- Abraham Lincoln Online

- The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln

- Lincoln Studies Center at Knox College

- Discussion of John Drinkwater's play Abraham Lincoln

- Original 1860's Harper's Weekly Images and News on Abraham Lincoln

- The Lincoln Log: A Daily Chronology of the Life of Abraham Lincoln

- Lincoln Memorial Washington, DC

- The Lincoln Museum Fort Wayne, Indiana

- The Lincoln Prize A national book award sponsored by The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History and the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College

- Abraham Lincoln's Assassination

- John Summerfield Staples, President Lincoln's "Substitute"

- US6469 Patent -- Manner of Buoying Vessels -- A. Lincoln -- 1849

- King Lincoln (an archive of articles on Lincoln)

- National Park Service Abraham Lincoln birthplace (includes good early history)

- Hoard Historical Museum in Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin with Lincoln Library

- On the Question of Lincoln's Sexuality

- Medical and Health history of Abraham Lincoln

- Biography (World of Biography)

Project Gutenberg eTexts

- List of Works by Abraham Lincoln at Project Gutenberg

- Richardson, James D. (compiler). A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents: Volume 6, part 1: Abraham Lincoln.

- Lincoln's Yarns and Stories.

- Hay, John (1890). Abraham Lincoln: a History.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)- "Volume 1". (1835 to 1905)

- "Volume 2". (1832 to 1901)

- Nicolay, Helen (1907). The Boys' Life of Abraham Lincoln. (1866 to 1954)

- Ketcham, Henry (1901). The Life of Abraham Lincoln.

- Morse, John T. (1899). Abraham Lincoln.

- Francis Fisher Browne (1913). The Every-day Life of Abraham Lincoln.

- George Haven Putnam, Litt. D. (1909). Abraham Lincoln: The People's Leader in the Struggle for National Existence.

- Stephenson, Nathaniel W. (1922). Lincoln's Personal Life.

| Preceded byJohn Henry | Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Illinois's 7th District 1847 – 1849 |

Succeeded byThomas Langrell Harris |

| Preceded byJohn Frémont | Republican Party presidential nominee 1860 (won), 1864 (won) |

Succeeded byUlysses Grant |

| Preceded byJames Buchanan | President of the United States March 4, 1861 – April 15, 1865 |

Succeeded byAndrew Johnson |

Categories:

- Abraham Lincoln

- Presidents of the United States

- Republican Party (United States) presidential nominees

- American Civil War people

- Assassinated politicians

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Illinois

- United States Senate candidates

- Members of the Illinois House of Representatives

- Autodidacts

- Firearm deaths

- American lawyers

- American murder victims

- Humanists

- People from Kentucky

- United States Army officers

- Welsh-Americans

- Cat lovers

- 1809 births

- 1865 deaths