| Revision as of 17:25, 8 August 2011 view sourceFayenatic london (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators335,707 editsm →Philosophy: "a bore", surely?← Previous edit | Revision as of 18:44, 19 August 2011 view source Macai (talk | contribs)632 edits →See alsoNext edit → | ||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| {{div col| |

{{div col|5}} | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| {{div col end}} | {{div col end}} | ||

Revision as of 18:44, 19 August 2011

"Boring" redirects here. For other uses, see Boring (disambiguation). For the Buzzcocks song, see Spiral Scratch (EP).

Boredom is an emotional state experienced when an individual is without any work or is not interested in their surroundings. The first recorded use of the word boredom is in the novel Bleak House by Charles Dickens, written in 1852, in which it appears six times, although the expression to be a bore had been used in the sense of "to be tiresome or dull" since 1768. The French term for boredom, ennui, is sometimes used in English as well.

Psychology

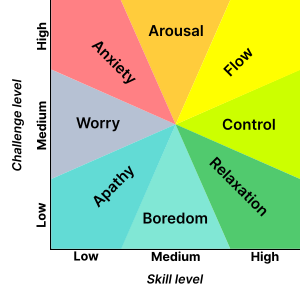

Boredom has been defined by C. D. Fisher in terms of its central psychological processes: “an unpleasant, transient affective state in which the individual feels a pervasive lack of interest in and difficulty concentrating on the current activity.” M. R. Leary and others describe boredom as “an affective experience associated with cognitive attentional processes.” In positive psychology, boredom is described as a response to a moderate challenge for which the subject has more than enough skill.

There are three types of boredom, all of which involve problems of engagement of attention. These include times when we are prevented from engaging in some wanted activity, when we are forced to engage in some unwanted activity, or when we are simply unable, for no apparent reason, to maintain engagement in any activity or spectacle. Boredom proneness is a tendency to experience boredom of all types. This is typically assessed by the Boredom Proneness Scale. Consistent with the definition provided above, recent research has found that boredom proneness is clearly and consistently associated with failures of attention. Boredom and boredom proneness are both theoretically and empirically linked to depression and depressive symptoms. Nonetheless, boredom proneness has been found to be as strongly correlated with attentional lapses as with depression. Although boredom is often viewed as a trivial and mild irritant, proneness to boredom has been linked to a very diverse range of possible psychological, physical, educational, and social problems.

Philosophy

Boredom is a condition characterized by perception of one's environment as dull, tedious, and lacking in stimulation. This can result from leisure and a lack of aesthetic interests. Labor, however, and even art may be alienated and passive, or immersed in tedium. There is an inherent anxiety in boredom; people will expend considerable effort to prevent or remedy it, yet in many circumstances, it is accepted as suffering to be endured. Common passive ways to escape boredom are to sleep or to think creative thoughts (daydream). Typical active solutions consist in an intentional activity of some sort, often something new, as familiarity and repetition lead to the tedious.

Boredom also plays a role in existentialist thought. In contexts where one is confined, spatially or otherwise, boredom may be met with various religious activities, not because religion would want to associate itself with tedium, but rather, partly because boredom may be taken as the essential human condition, to which God, wisdom, or morality are the ultimate answers. Boredom is in fact taken in this sense by virtually all existentialist philosophers as well as by Schopenhauer.

Heidegger wrote about boredom in two texts available in English, in the 1929/30 semester lecture course The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics, and again in the essay What is Metaphysics? published in the same year. In the lecture, Heidegger included about 100 pages on boredom, probably the most extensive philosophical treatment ever of the subject. He focused on waiting at train stations in particular as a major context of boredom. In Kierkegaard's remark in Either/Or, that "patience cannot be depicted" visually, there is a sense that any immediate moment of life may be fundamentally tedious.

Blaise Pascal in the Pensées discusses the human condition in saying "we seek rest in a struggle against some obstacles. And when we have overcome these, rest proves unbearable because of the boredom it produces", and later states that "only an infinite and immutable object – that is, God himself – can fill this infinite abyss."

Without stimulus or focus, the individual is confronted with nothingness, the meaninglessness of existence, and experiences existential anxiety. Heidegger states this idea nicely: "Profound boredom, drifting here and there in the abysses of our existence like a muffling fog, removes all things and men and oneself along with it into a remarkable indifference. This boredom reveals being as a whole." Arthur Schopenhauer used the existence of boredom in an attempt to prove the vanity of human existence, stating, "...for if life, in the desire for which our essence and existence consists, possessed in itself a positive value and real content, there would be no such thing as boredom: mere existence would fulfil and satisfy us."

Erich Fromm and other thinkers of critical theory speak of boredom as a common psychological response to industrial society, where people are required to engage in alienated labor. According to Fromm, boredom is "perhaps the most important source of aggression and destructiveness today." For Fromm, the search for thrills and novelty that characterizes consumer culture are not solutions to boredom, but mere distractions from boredom which, he argues, continues unconsciously. Above and beyond taste and character, the universal case of boredom consists in any instance of waiting, as Heidegger noted, such as in line, for someone else to arrive or finish a task, or while one is travelling somewhere. The automobile requires fast reflexes, making its operator busy and hence, perhaps for other reasons as well, making the ride more tedious despite being over sooner.

Causes and effects

Although it has not been widely studied, research on boredom suggests that boredom is a major factor impacting diverse areas of a person's life. People ranked low on a boredom-proneness scale were found to have better performance in a wide variety of aspects of their lives, including career, education, and autonomy. Boredom can be a symptom of clinical depression. Boredom can be a form of learned helplessness, a phenomenon closely related to depression. Some philosophies of parenting propose that if children are raised in an environment devoid of stimuli, and are not allowed or encouraged to interact with their environment, they will fail to develop the mental capacities to do so.

In a learning environment, a common cause of boredom is lack of understanding; for instance, if one is not following or connecting to the material in a class or lecture, it will usually seem boring. However, the opposite can also be true; something that is too easily understood, simple or transparent, can also be boring. Boredom is often inversely related to learning, and in school it may be a sign that a student is not challenged enough, or too challenged. An activity that is predictable to the students is likely to bore them.

A study of 1989 indicated that an individual's impression of boredom may be influenced by the individual's degree of attention, as a higher acoustic level of distraction from the environment correlated with higher reportings of boredom.

Boredom has been studied as being related to drug abuse among teens. Boredom has been proposed as a cause of pathological gambling behavior. A study found results consistent with the hypothesis that pathological gamblers seek stimulation to avoid states of boredom and depression.

Popular culture

In Chapter 18 of the novel The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde (1854–1900), the character Lord Henry Wotton says to a young Dorian Gray: "The only horrible thing in the world is ennui, Dorian. That is the one sin for which there is no forgiveness." John Sebastian, Iggy Pop, the Deftones, Buzzcocks, and Blink-182 have all written songs with boredom mentioned in the title. Other songs about boredom and activities people turn to when bored include Green Day's song "Longview", System of a Down's "Lonely Day", and Bloodhound Gang's "Mope". Douglas Adams depicted a robot named Marvin the Paranoid Android whose boredom appeared to be the defining trait of his existence in The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.

The 1969 Vocational Guidance Counsellor sketch on Monty Python's Flying Circus established a lasting stereotype of accountants as boring. The Yellow Pages used to carry an entry under Boring, "See civil engineers", but this was changed in 1996 to "See sites exploration."

See also

References

- Oxford Old English Dictionary

- Online Etymology Dictionary

- ^ Csikszentmihalyi M (1997). Finding Flow: The Psychology of Engagement with Everyday Life (1st ed.). New York: Basic Books. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-465-02411-7. Cite error: The named reference "Finding Flow" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Fisher 1993, p. 396

- Leary, M. R., Rogers, P. A., Canfield, R. W., Coe, C. (1986). "Boredom in interpersonal encounters: Antecedents and social implications". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 51: 968–975, p. 968. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.5.968.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cheyne, J. A., Carriere, J. S. A., Smilek, D. (2006). "Absent-mindedness: Lapses in conscious awareness and everyday cognitive failures". Consciousness and Cognition. 15 (3): 578–592. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2005.11.009. PMID 16427318.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Farmer, R., Sundberg, N. D. (1986). "Boredom proneness: The development and correlates of a new scale". Journal of Personality Assessment. 50 (1): 4–17. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5001_2. PMID 3723312.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Fisher, C.D. (1993). "Boredom at work: A neglected concept". Human Relations. 46: 395–417. doi:10.1177/001872679304600305.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Carriere, J. S. A., Cheyne, J. A., Smilek, D. (September 2008). "Everyday Attention Lapses and Memory Failures: The Affective Consequences of Mindlessness" (PDF). Consciousness and Cognition. 17 (3): 835–847. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2007.04.008. PMID 17574866.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sawin, D. A., Scerbo, M. W. (1995). "Effects of instruction type and boredom proneness in vigilance: Implications for boredom and workload". Human Factors. 37 (4): 752–765. doi:10.1518/001872095778995616. PMID 8851777.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Vodanovich, S. J., Verner, K. M., Gilbride, T. V. (1991). "Boredom proneness: Its relationship to positive and negative affect". Psychological Reports. 69 (3 Pt 2): 1139–46. doi:10.2466/PR0.69.8.1139-1146. PMID 1792282.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Martin Heidegger. The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics, pp. 78–164.

- Pascal, Blaise; Ariew, Roger (2005). Pensées. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Pub. Co. ISBN 9780872207172. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- Martin Heidegger, What is Metaphysics? (1929)

- Arthur Schopenhauer, Essays and Aphorisms, Penguin Classics, ISBN 0140442278 (2004), p53 Full text available online: Google Books Search

- Erich Fromm, "Theory of Aggression" pg.7

- Watt, J. D., Vodanovich, S. J. (1999). "Boredom Proneness and Psychosocial Development". Journal of Psychology. 133 (1): 149–155. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(200001)56:1<149::AID-JCLP14>3.0.CO;2-Y.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ed.gov – R.V. Small et al. Dimensions of Interest and Boredom in Instructional Situations, Proceedings of Selected Research and Development Presentations at the 1996 National Convention of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology (18th, Indianapolis, IN), (1996)

- Damrad-Frye, R (1989). "The experience of boredom: the role of the self-perception of attention". J Personality Social Psych. 57: 315–20. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.2.315.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Iso-Ahola, Seppo E.; Crowley, Edward D. (1991). "Adolescent Substance Abuse and Leisure Boredom". Journal of Leisure Research. 23 (3): 260–71.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Blaszczynski A, McConaghy N, Frankova A (1990). "Boredom proneness in pathological gambling". Psychol Rep. 67 (1): 35–42. doi:10.2466/PR0.67.5.35-42. PMID 2236416.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Learn the elementary bits about business, Financial Times, 14 October 2008

- Exciting times for London civil engineers, Chicago Sun Times, 23 August 1996