| Revision as of 15:18, 21 March 2006 editGhirlandajo (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers89,661 edits Reverted edits by Molobo (talk) to last version by YurikBot← Previous edit | Revision as of 16:02, 21 March 2006 edit undoPiotrus (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Event coordinators, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers286,198 editsm Reverted edits by Ghirlandajo (talk) to last version by MoloboNext edit → | ||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

| Suvorov was born in ] into a noble family of ] descent. He entered the army as a boy, served against the ]s in ] and against the ]ns during the ] (1756 - 1763). After repeatedly distinguishing himself in battle he became a colonel in 1762. | Suvorov was born in ] into a noble family of ] descent. He entered the army as a boy, served against the ]s in ] and against the ]ns during the ] (1756 - 1763). After repeatedly distinguishing himself in battle he became a colonel in 1762. | ||

| Suvorov next served in ] during the ], dispersed the Polish forces under ], |

Suvorov next served in ] during the ], dispersed the Polish forces under ], captured ] (1768) paving the way for the ] and reached the rank of major-general. The ] saw his first campaigns against the ]s in 1773–1774, and particularly in the battle of ], he laid the foundations of his reputation. | ||

| In 1775, Suvorov was dispatched to suppress the rebellion of ], but arrived at the scene only in time to conduct the first interrogation of the rebel leader, who had been betrayed by his fellow ], and eventually beheaded in Moscow. | In 1775, Suvorov was dispatched to suppress the rebellion of ], but arrived at the scene only in time to conduct the first interrogation of the rebel leader, who had been betrayed by his fellow ], and eventually beheaded in Moscow. | ||

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 16:02, 21 March 2006

Suvorov links here. For information about the spy, see Viktor Suvorov.Alexander Vasilyevich Suvorov (Template:Lang-ru) (sometimes transliterated as Aleksandr, Aleksander and Suvarov), Count Suvorov of Rymnik, Prince of Italy (граф Рымникский, князь Италийский) (November 24, 1729 – May 18, 1800), was a Russian general, one of the few great generals in history who never lost a battle. He was famed for his manual The Science of Victory, and noted for the saying "Train hard, fight easy."

Early life and career

Suvorov was born in Moscow into a noble family of Novgorod descent. He entered the army as a boy, served against the Swedes in Finland and against the Prussians during the Seven Years' War (1756 - 1763). After repeatedly distinguishing himself in battle he became a colonel in 1762.

Suvorov next served in Poland during the Confederation of Bar, dispersed the Polish forces under Pułaski, captured Kraków (1768) paving the way for the first partition of Poland and reached the rank of major-general. The Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774 saw his first campaigns against the Turks in 1773–1774, and particularly in the battle of Kozludji, he laid the foundations of his reputation.

In 1775, Suvorov was dispatched to suppress the rebellion of Pugachev, but arrived at the scene only in time to conduct the first interrogation of the rebel leader, who had been betrayed by his fellow Cossacks, and eventually beheaded in Moscow.

Scourge of the Poles and the Turks

From 1777 to 1783 Suvorov served in the Crimea and in the Caucasus, becoming a lieutenant-general in 1780, and general of infantry in 1783, upon completion of his tour of duty there. From 1787 to 1791 he again fought the Turks during the Russo-Turkish War of 1787–1792 and won many victories; he was wounded twice at Kinburn (1787), took part in the siege of Ochakov, and in 1788 won two great victories at Focsani and by the river Rimnik.

In both these battles an Austrian corps under Prince Josias of Saxe-Coburg participated, but at Rimnik Suvorov was in command of the whole allied forces. For the latter victory, Catherine the Great made Suvorov a count with the name "Rimniksky" in addition to his own name, and the Emperor Joseph II made him a count of the Holy Roman Empire. On 22 December 1790 Suvorov successfully stormed the reputedly impenetrable fortress of Ismail in Bessarabia. Turkish forces inside the fortress had the orders to stand their ground to the end and haughtily declined the Russian ultimatum. Their defeat was seen as a major catastrophe in the Ottoman empire, but in Russia it was glorified in the first national anthem, Let the thunder of victory sound!

Immediately after the peace with Turkey was signed, Suvorov was again transferred to Poland, where he assumed the command of one of the corps and took part in the Battle of Maciejowice, in which he captured the Polish commander-in-chief Tadeusz Kościuszko. On November 4, 1794, Suvorov's forces stormed Warsaw and captured Praga, one of its boroughs. The massacre of approximately 20,000 civilians in Praga broke the spirits of the defenders and soon put an end to the Kościuszko Uprising.

It is said that the Russian commander sent a report to his sovereign consisting of only three words: Hurrah from Warsaw, Suvorov. The Empress of Russia replied equally briefly: Congratulations, Field Marshal. Catherine. The newly-appointed field marshal remained in Poland until 1795, when he returned to Saint Petersburg. But his sovereign and friend Catherine died in 1796, and her successor Paul I dismissed the veteran in disgrace.

Suvorov's Italian campaign

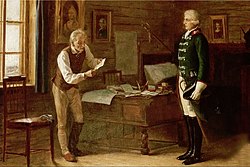

Suvorov spent the next few years in retirement on his estate Konchanskoe near Borovichi. He criticised the new military tactics and dress introduced by the emperor, and some of his caustic verse reached the ears of Paul. His conduct therefore came under surveillance and his correspondence with his wife, who had remained at Moscow - for his marriage relations had not been happy - was tampered with. On Sundays he tolled the bell for church and sang among the rustics in the village choir. On week days he worked among them in a smock frock. But in February 1799 Emperor Paul I summoned him to take the field again, this time against the French Revolutionary armies in Italy.

The campaign opened with a series of Suvorov's victories (Cassano d'Adda, Trebbia, Novi). This reduced the French government to desperate straits and drove every French soldier from Italy, save for the handful under Moreau, which maintained a foothold in the Maritime Alps and around Genoa. Suvorov himself gained the rank of "prince of the House of Savoy" from king of Sardinia.

But the later events of the eventful year went uniformly against the Russians. General Korsakov's force was defeated by Masséna at Zürich. Betrayed by the Austrians, the old field marshal, seeking to make his way over the Swiss passes to the Upper Rhine, had to retreat to Vorarlberg, where the army, much shattered and almost destitute of horses and artillery, went into winter quarters. When Suvorov battled his way through the snow-capped Alps his army was checked but never defeated. For this marvel of strategic retreat, unheard of since the time of Hannibal, Suvorov was raised to the unprecedented rank of generalissimo. He was officially promised to be given the military triumph in Russia but the court intrigues led the Emperor Paul to cancel the ceremony.

Early in 1800 Suvorov returned to Saint Petersburg. Paul refused to give him an audience, and, worn out and ill, the old veteran died a few days afterwards on 18 May 1800, at Saint Petersburg. Lord Whitworth, the English ambassador, and the poet Derzhavin were the only persons of distinction present at the funeral.

Suvorov lies buried in the church of the Annunciation in the Alexander Nevsky Monastery, the simple inscription on his grave stating, according to his own direction, "Here lies Suvorov". But within a year of his death the tsar Alexander I erected a statue to his memory in the Field of Mars (Saint Petersburg).

His progeny and titles

His full name and titles (according to Russian pronunciation), ranks and awards are the following: Aleksandr Vasiliyevich Suvorov, Prince of Italy, Count of Rimnik , Count of the Holy Roman Empire, Prince of Sardinia, Generalissimo of Russia's Ground and Naval forces, Field Marshal of the Austrian and Sardinian Armies; seriously wounded six times, he was the recipient of the Order of St. Andrew the First Called Apostle, Order of St. George the Triumphant First Class, Order of St. Vladimir First Class, Order of Alexander Nevsky, Order of St. Anna First Class, Grand Cross of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, (Austria) Order of Maria Teresia First Class, (Prussia) Order of the Black Eagle, Order of the Red Eagle, the Pour le Merite, (Sardinia) Order of the Revered Saints Maurice and Lazarus, (Bavaria) Order of St. Gubert, the Golden Lionness, (France) Order of the Carmelite Virgin Mary, St. Lasara, (Poland) Order of the White Eagle, the Order of St. Stanislaus.

Suvorov's son Arkadi (1783 - 1811) served as a general officer in the Russian army during the Napoleonic and Turkish wars of the early 19th century, and drowned in the same river Rimnik that had brought his father so much fame. His grandson Alexander Arkadievich (1804 - 1882) also became a Russian general.

Assessment

The Russians long cherished the memory of Suvorov. A great captain, viewed from the standpoint of any age of military history, he functions specially as the great captain of the Russian nation, for the character of his leadership responded to the character of the Russian soldier. In an age when war had become an act of diplomacy he restored its true significance as an act of force. He had a great simplicity of manner, and while on a campaign lived as a private soldier, sleeping on straw and contenting himself with the humblest fare. But he had himself passed through all the gradations of military service.

His gibes procured him many enemies. He had all the contempt of a man of ability and action for ignorant favourites and ornamental carpet-knights. But his drolleries served sometimes to hide, more often to express, a soldierly genius, the effect of which the Russian army did not soon outgrow. If the tactics of the Russians in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904 - 1905 reflected too literally some of the maxims of Suvorov’s Turkish wars, the spirit of self-sacrifice, resolution and indifference to losses there shown formed a precious legacy from those wars. Mikhail Ivanovich Dragomirov declared that he based his teaching on Suvorov's practice, which he held representative of the fundamental truths of war and of the military qualities of the Russian nation.

The magnificent Suvorov museum of military history was opened in 1904. Apart from St Petersburg, other Suvorov monuments have been erected in Ochakov (1907), Sevastopol, Izmail, Tulchin, Kobrin, Ladoga, Kherson, Timanovka, Simferopol, Kaliningrad, Konchanskoe, Rymnik, and in the Swiss Alps. On July 29, 1942 The Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR established the Order of Suvorov. It was awarded for successful offensive actions against superior enemy forces.

Note

- : Ledonne, 2003, p.144 and Alexander, 1989, p.317

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)- John T. Alexander, Catherine the Great: Life and Legend, Oxford University Press US, 1999, ISBN 0195061624

- John P. Ledonne, The Grand Strategy of the Russian Empire, Oxford University Press US, 2003, 0195161009

Further reading

- Anthing, Versuch einer Kriegsgeschichte des Grafen Suworow (Gotha, 1796 - 1799)

- F. von Smut, Suworows Leben und Heerzüge (Vilna, 1833—1834) and Suworow and Polens Untergang (Leipzig, 1858,)

- Von Reding-Biberegg, Der Zug Suworows durch die Schweiz (Zürich 1896)

- Lieut.-Colonel Spalding, Suvorof (London, 1890)

- G. von Fuchs, Suworows Korrespondenz, 1799 (Glogau, 1835)

- Souvorov en Italie by Gachot, Masséna’s biographer (Paris, 1903)

- The standard Russian biographies of Polevoi (1853; Ger. trans., Mitau, 1853); Rybkin (Moscow, 1874), Vasiliev (Vilna, 1899), Meshcheryakov and Beskrovnyi (Moscow, 1946), and Osipov (Moscow, 1955).

- The Russian examinations of his martial art, by Bogolyubov (Moscow, 1939) and Nikolsky (Moscow, 1949).

External links

- Alexander V. Suvorov: Russian Field Marshal, 1729-1800

- Speed, Assessment, and Hitting Power: Suvorov's Art of Victory

- Suvorov military musum in St Petersburg

- Russian Army during the Napoleonic Wars

- Suvorov's home and family