| Revision as of 06:53, 29 December 2011 editChaiyan anantasat (talk | contribs)164 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 06:59, 29 December 2011 edit undoChaiyan anantasat (talk | contribs)164 editsNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{History of Malta}} | |||

| '''British Malta''' In 1800, Malta voluntarily became part of the ]. Under the terms of the 1802 | '''British Malta''' In 1800, Malta voluntarily became part of the ]. Under the terms of the 1802 | ||

| ], Britain was supposed to evacuate the island, but failed to keep this obligation – one of several mutual cases of non-adherence to the treaty, which eventually led to its collapse and the resumption of war between Britain and France.{{Citation needed|date=August 2007}} | ], Britain was supposed to evacuate the island, but failed to keep this obligation – one of several mutual cases of non-adherence to the treaty, which eventually led to its collapse and the resumption of war between Britain and France.{{Citation needed|date=August 2007}} | ||

Revision as of 06:59, 29 December 2011

| Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Malta |

|

| Ancient history |

| Middle Ages |

| Modern history |

| British Period |

| Independent Malta |

|

|

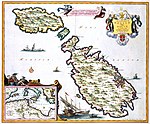

British Malta In 1800, Malta voluntarily became part of the British Empire. Under the terms of the 1802 Treaty of Amiens, Britain was supposed to evacuate the island, but failed to keep this obligation – one of several mutual cases of non-adherence to the treaty, which eventually led to its collapse and the resumption of war between Britain and France.

Although initially the island was not given much importance, its excellent harbours became a prized asset for the British, especially after the opening of the Suez canal. The island became a military and naval fortress, the headquarters of the British Mediterranean fleet.

Home rule was refused to the Maltese until 1921 although a partly elected legislative council was created as early as 1849, and the locals sometimes suffered considerable poverty. This was due to the island being overpopulated and largely dependent on British military expenditure which varied with the demands of war. Throughout the 19th century, the British administration instituted several liberal constitutional reforms which were generally resisted by the Church and the Maltese elite who preferred to cling to their feudal privileges. Political organizations, like the Nationalist Party, were created or had as one of their aims, the protection of the Italian language in Malta.

In 1919, there were riots over the excessive price of bread. These would lead to greater autonomy for the locals. Malta obtained a bicameral parliament with a Senate (abolished in 1949) and an elected Legislative Assembly. The Constitution was suspended twice. In 1930 it was suspended that a free and fair election would not be possible following a clash between the governing Constitutional Party and the Church and the latter's subsequent imposition of mortal sin on voters of the party and its allies. In 1934 the Constitution was revoked over the Government's budgetary vote for the teaching of Italian in elementary schools.

Language issue

Before the arrival of the British, the official language since 1530 (and the one of the educated elite) had been Italian, but this was downgraded by the increased use of English. In 1934, English and Maltese were declared the sole official languages.

In 1934, only about 15% of the population could speak Italian fluently. This meant that out of 58,000 males qualified by age to be jurors, only 767 could qualify by language, as only Italian had till then been used in the courts. This injustice carried more weight than concerns over fascism.

World War II

See also: Siege of Malta (1940)Before World War II, Valletta was the location of the Royal Navy's Mediterranean Fleet's headquarters. However, despite Winston Churchill's objections, the command was moved to Alexandria, Egypt, in April 1937 fearing it was too susceptible to air attacks from Europe. At the time of the Italian declaration of war (10 June 1940), Malta had a garrison of less than four thousand soldiers and about five weeks' of food supplies for the population of about three hundred thousand. In addition, Malta's air defences consisted of about forty-two anti-aircraft guns (thirty-four "heavy" and eight "light") and four Gloster Gladiators, for which three pilots were available.

Being a British colony, situated close to Sicily and the Axis shipping lanes, Malta was bombarded by the Italian and German air forces. Malta was used by the British to launch attacks on the Italian navy and had a submarine base. It was also used as a listening post, reading German radio messages including Enigma traffic.

The first air raids against Malta occurred on 11 June 1940; there were six attacks that day. The island's biplanes were unable to defend due to the Luqa Airfield being unfinished; however, the airfield was ready by the seventh attack. Initially, the Italians would fly at about 5,500 m, then they dropped down to three thousand metres (in order to improve the accuracy of their bombs). Major Paine stated, ", we bagged one or two every other day, so they started coming in at . Their bombing was never very accurate. As they flew higher it became quite indiscriminate." Mabel Strickland would state, "The Italians decided they didn't like , so they dropped their bombs twenty miles off Malta and went back."

By the end of August, the Gladiators were reinforced by twelve Hawker Hurricanes which had arrived via HMS Argus. During the first five months of combat, the island's aircraft destroyed or damaged about thirty-seven Italian aircraft. Italian fighter pilot Francisco Cavalera observed, "Malta was really a big problem for us—very well-defended."

On Malta, 330 people had been killed and 297 were seriously wounded from the war's inception until December 1941. In January 1941, the German X. Fliegerkorps arrived in Sicily as the Afrika Korps arrived in Libya. Over the next four months 820 people were killed and 915 seriously wounded.

On 15 April 1942, King George VI awarded the George Cross (the highest civilian award for gallantry) "to the island fortress of Malta — its people and defenders." Franklin D. Roosevelt arrived on 8 December 1943, and presented a United States Presidential Citation to the people of Malta on behalf of the people of United States. He presented the scroll on 8 December, but dated it 7 December for symbolic reasons. In part it read: "Under repeated fire from the skies, Malta stood alone and unafraid in the center of the sea, one tiny bright flame in the darkness -- a beacon of hope for the clearer days which have come." (The complete citation now stands on a plaque on the wall of the Grand Master's Palace on Republic Street in the town square of Valletta.)

Attempted integration with the United Kingdom

After World War II, the islands achieved self-rule, with the Malta Labour Party (MLP) of Dom Mintoff seeking either full integration with the UK or else "self-determination (independence), and the Partit Nazzjonalista (PN) of Dr. George Borg Olivier favouring independence, with the same "dominion status" that Canada, Australia and New Zealand enjoyed.

In December 1955, a Round Table Conference was held in London, on the future of Malta, attended by Mintoff, Borg Olivier and other Maltese politicians, along with the British Colonial Secretary, Alan Lennox-Boyd. The British government agreed to offer the islands their own representation in the British House of Commons, with the Home Office taking over responsibility for Maltese affairs from the Colonial Office.

Under the proposals, the Maltese Parliament would retain responsibility over all affairs except defence, foreign policy, and taxation. The Maltese were also to have social and economic parity with the UK, to be guaranteed by the British Ministry of Defence (MoD), the islands' main source of employment. A referendum was held on 14 February 1956, in which 77.02 per cent of voters were in favour of the proposal, but owing to a boycott by the Nationalist Party, only 59.17 per cent of the electorate voted, thereby rendering the result inconclusive.

In addition, the decreasing strategic importance of Malta to the Royal Navy meant that the British government was increasingly reluctant to maintain the naval dockyards. Following a decision by the Admiralty to dismiss 40 workers at the dockyard, Mintoff declared that "representatives of the Maltese people in Parliament declare that they are no longer bound by agreements and obligations toward the British government..." In response, the Colonial Secretary sent a cable to Mintoff, stating that he had "recklessly hazarded" the whole integration plan. This led to the islands being placed under direct rule from London, with the MLP abandoning support for integration and now advocating independence.

While France had implemented a similar policy in its colonies, some of which became overseas departments, the status offered to Malta from Britain constituted a unique exception. Malta was the only British colony where integration with the UK was seriously considered, and subsequent British governments have ruled out integration for remaining overseas territories, such as Gibraltar.

| Former British Empire and Current British Overseas Territories | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

References

- Stephenson, Charles. The Fortifications of Malta 1530–1945. Great Britain: Osprey Publishing Ltd., 2004.

- Attard, Joseph. Britain and Malta. Malta: PEG Ltd.1988.

- Luke, Sir Harry. Malta – An Account and an Appreciation. Great Britain: Harrap, 1949.

- Attard P.76

- Luke ChVIII

- Attard P.64:Luke P.107

- http://www.doi.gov.mt/en/islands/prime_ministers/strickland_gerald.asp

- http://www.intratext.com/IXT/ITA2413/_P6.HTM

- ^ Luke P.113

- ^ Bierman, John; & Colin Smith (2002). The Battle of Alamein: Turning Point, World War II. Viking. p. 36. ISBN 978-0670030408.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Titterton, G. A. (2002). The Royal Navy and the Mediterranean, Volume 2. Psychology Press. p. xiii. ISBN 978-0714651798.

- Elliott, Peter (1980). The Cross and the Ensign: A Naval History of Malta, 1798-1979. Naval Institute Press. p. ??. ISBN 978-0870219269.

- Calvocoressi, Peter (1981 (reprint)). Top Secret Ultra - Volume 10 of Ballantine Espionage Intelligence Library. Ballantine Books. pp. 42, 44. ISBN 978-0345300690.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Bierman & Smith. p. 37.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Bierman & Smith. p. 38.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Shankland, Peter; & Anthony Hunter (1961). Malta Convoy. I. Washburn. p. 60.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Mr. Roosevelt Gives Scroll To People On Isle Of Malta". The Gettysburg Times. Associated Press. December 10, 1943. pp. 1, 4.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Rudolf, Uwe Jens; & Warren G. Berg (2010). Historical Dictionary of Malta. Scarecrow Press. pp. 197–198. ISBN 978-0810853171.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Referenda in Malta: The Questions and the Voters' Responses

- ^ "Penny-Wise", TIME, January 13, 1958

- Hansard 3 August 1976 Written Answers (House of Commons) → Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs