| Revision as of 21:04, 17 June 2012 editYobol (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers15,179 edits →Typical scan dose: undue WP:WEIGHT to isolated incidents← Previous edit | Revision as of 21:15, 17 June 2012 edit undoYobol (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers15,179 edits →Typical scan dose: restore previous table; the one cited does not appear to be fully supported by citations (some numbers do not appear in sources which is cited)Next edit → | ||

| Line 84: | Line 84: | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| !Examination | !Examination | ||

| !Typical ]</br> (] = ] for X-rays<ref name=FDADose>{{cite web|title=What are the Radiation Risks from CT?|url=http://www.fda.gov/radiation-emittingproducts/radiationemittingproductsandprocedures/medicalimaging/medicalx-rays/ucm115329.htm|work=Food and Drug Administration|year=2009}}</ref>) | |||

| !Typical ] (]) | |||

| ! (millirem) | |||

| !Typical ] (]) | |||

| ! ] (])<br></sub> | |||

| ! Dose in number of<br>years it would take<br>the irradiated body part<br>to absorb the same energy<br>from background radiation | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |X-ray Personnel security screening scan | |X-ray Personnel security screening scan | ||

| |0.00025 | |||

| |0. |

|0.025<ref>", US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), October 12, 2010</ref> | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| |Chest X-ray | |Chest X-ray | ||

| ⚫ | |0.02<ref name=FDADose/> | ||

| |0.1 | |||

| |10 | |||

| |0.01-0.15<ref name="crfdr"></ref> | |||

| |0.01-0.15<ref name="crfdr"/> | |||

| |0.003-0.05<ref name="crfdr"/> | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |Head CT | |Head CT | ||

| |1.5<ref name="nrpb2005">Shrimpton, P.C; Miller, H.C; Lewis, M.A; Dunn, M. </ref> | |1.5<ref name="nrpb2005">Shrimpton, P.C; Miller, H.C; Lewis, M.A; Dunn, M. </ref>-2<ref name=FDADose/> | ||

| |150 | |||

| |64<ref name="nrpb2005"/> | |||

| |64<ref name="nrpb2005"/> | |||

| |21<ref name="nrpb2005"/> | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |Screening ] | |Screening ] | ||

| |3<ref name="NEJM-radiation"/> | |3<ref name="NEJM-radiation"/> | ||

| |300 | |||

| |3<ref name="crfdr"/> | |||

| |3<ref name="crfdr"/> | |||

| |1<ref name="crfdr"/> | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |Abdomen CT | |Abdomen CT | ||

| |5.3<ref name="nrpb2005"/> | |5.3<ref name="nrpb2005"/> | ||

| |530 | |||

| |14<ref name="nrpb2005"/> | |||

| |14<ref name="nrpb2005"/> | |||

| |4.6<ref name="nrpb2005"/> | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |Chest CT | |Chest CT | ||

| |5.8<ref name="nrpb2005"/> | |5.8<ref name="nrpb2005"/>-8<ref name=FDADose/> | ||

| |580 | |||

| |13<ref name="nrpb2005"/> | |||

| |13<ref name="nrpb2005"/> | |||

| |4.3<ref name="nrpb2005"/> | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |CT colonography (]) | |CT colonography (]) | ||

| |3.6–8.8 | |3.6–8.8 | ||

| |360–880 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |Chest, abdomen and pelvis CT | |Chest, abdomen and pelvis CT | ||

| |9.9<ref name="nrpb2005"/> | |9.9<ref name="nrpb2005"/> | ||

| |990 | |||

| |12<ref name="nrpb2005"/> | |||

| |12<ref name="nrpb2005"/> | |||

| |4<ref name="nrpb2005"/> | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |Cardiac CT angiogram | |Cardiac CT angiogram | ||

| |6.7-13<ref>{{cite web|url=http://radiology.rsnajnls.org/cgi/content/abstract/226/1/145 |title=Radiation Exposure during Cardiac CT: Effective Doses at Multi–Detector Row CT and Electron-Beam CT |publisher=Radiology.rsnajnls.org |

|6.7-13<ref>{{cite web|url=http://radiology.rsnajnls.org/cgi/content/abstract/226/1/145 |title=Radiation Exposure during Cardiac CT: Effective Doses at Multi–Detector Row CT and Electron-Beam CT |publisher=Radiology.rsnajnls.org|date=2002-11-21 |accessdate=2009-10-13}}</ref> | ||

| |670–1300 | |||

| |40-100<ref name="crfdr"/> | |||

| |40-100<ref name="crfdr"/> | |||

| |<33<ref name="crfdr"/> | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |] | |] | ||

| |15<ref name="NEJM-radiation"/> | |15<ref name="NEJM-radiation"/> | ||

| |1500 | |||

| |15<ref name="crfdr"/> | |||

| |15<ref name="crfdr"/> | |||

| |5<ref name="crfdr"/> | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |Neonatal abdominal CT | |Neonatal abdominal CT | ||

| |20<ref name="NEJM-radiation"/> | |20<ref name="NEJM-radiation"/> | ||

| |2000 | |||

| |20<ref name="crfdr"/> | |||

| ⚫ | |} | ||

| |20<ref name="crfdr"/> | |||

| ⚫ | | |

||

| ⚫ | |} | ||

| The following table include data of typical scan doses, as were observed in a survey of a few CT machines. The data represent an average of the observed values, however the maximal observed values in the survey were about two times higher than the average values |

The following table include data of typical scan doses, as were observed in a survey of a few CT machines. The data represent an average of the observed values, however the maximal observed values in the survey were about two times higher than the average values. The table include data for a few specific scanning protocols, however other scanning protocols of the same body parts exist, and some of which subject patients to greater radiation.<ref></ref> In some studies, the same body part is scanned twice, once without contrast agent, and once with contrast agent, which doubles the stated scan dose. | ||

| For purposes of comparison, the average ] in the UK is 1-3 mSv per year. | |||

| ===Radiation dose units=== | ===Radiation dose units=== | ||

Revision as of 21:15, 17 June 2012

For non medical computed tomography, see Industrial CT Scanning. "catSCAN" redirects here. For the Transformers character, see Transformers: Universe. Medical intervention| X-ray computed tomography | |

|---|---|

| File:Rosies ct scan.jpgA patient is receiving a CT scan for cancer. Outside of the scanning room is an imaging computer that reveals a 3D image of the body's interior. | |

| ICD-10-PCS | B?2 |

| ICD-9-CM | 88.38 |

| MeSH | D014057 |

| OPS-301 code | 3-20...3-26 |

| [edit on Wikidata] | |

X-ray computed tomography, also computed tomography (CT scan) or computed axial tomography (CAT scan), can be used for medical imaging and industrial imaging methods employing tomography created by computer processing. Digital geometry processing is used to generate a three-dimensional image of the inside of an object from a large series of two-dimensional X-ray images taken around a single axis of rotation.

CT produces a volume of data that can be manipulated, through a process known as "windowing", in order to demonstrate various bodily structures based on their ability to block the X-ray beam. Although historically the images generated were in the axial or transverse plane, perpendicular to the long axis of the body, modern scanners allow this volume of data to be reformatted in various planes or even as volumetric (3D) representations of structures. Although most common in medicine, CT is also used in other fields, such as nondestructive materials testing. Another example is archaeological uses such as imaging the contents of sarcophagi.

Usage of CT has increased dramatically over the last two decades in many countries. An estimated 72 million scans were performed in the United States in 2007. It is estimated that 0.4% of current cancers in the United States are due to CTs performed in the past and that this may increase to as high as 1.5-2% with 2007 rates of CT usage; however, this estimate is disputed.

Diagnostic use

Since its introduction in the 1970s, CT has become an important tool in medical imaging to supplement X-rays and medical ultrasonography. It has more recently been used for preventive medicine or screening for disease, for example CT colonography for patients with a high risk of colon cancer, or full-motion heart scans for patients with high risk of heart disease. A number of institutions offer full-body scans for the general population.

Head

Main article: CT head

CT scanning of the head is typically used to detect infarction, tumours, calcifications, haemorrhage and bone trauma. Of the above, hypodense (dark) structures indicate infarction or tumours, hyperdense (bright) structures indicate calcifications and haemorrhage and bone trauma can be seen as disjunction in bone windows. Ambulances equipped with small bore multi-sliced CT scanners respond to cases involving stroke or head trauma.

Lungs

CT can be used for detecting both acute and chronic changes in the lung parenchyma, that is, the internals of the lungs. It is particularly relevant here because normal two-dimensional X-rays do not show such defects. A variety of techniques are used, depending on the suspected abnormality. For evaluation of chronic interstitial processes (emphysema, fibrosis, and so forth), thin sections with high spatial frequency reconstructions are used; often scans are performed both in inspiration and expiration. This special technique is called high resolution CT. Therefore, it produces a sampling of the lung and not continuous images.

Pulmonary angiogram

CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) is a medical diagnostic test used to diagnose pulmonary embolism (PE). It employs computed tomography and an iodine based contrast agent to obtain an image of the pulmonary arteries.

Cardiac

Main article: Cardiac CTWith the advent of subsecond rotation combined with multi-slice CT (up to 320-slices), high resolution and high speed can be obtained at the same time, allowing excellent imaging of the coronary arteries (cardiac CT angiography).

Abdominal and pelvic

Main article: Abdominal and pelvic CTCT is a sensitive method for diagnosis of abdominal diseases. It is used frequently to determine stage of cancer and to follow progress. It is also a useful test to investigate acute abdominal pain.

Extremities

CT is often used to image complex fractures, especially ones around joints, because of its ability to reconstruct the area of interest in multiple planes. Fractures, ligamentous injuries and dislocations can easily be recognised with a 0.2 mm resolution.

Advantages

There are several advantages that CT has over traditional 2D medical radiography. First, CT completely eliminates the superimposition of images of structures outside the area of interest. Second, because of the inherent high-contrast resolution of CT, differences between tissues that differ in physical density by less than 1% can be distinguished. Finally, data from a single CT imaging procedure consisting of either multiple contiguous or one helical scan can be viewed as images in the axial, coronal, or sagittal planes, depending on the diagnostic task. This is referred to as multiplanar reformatted imaging.

CT is regarded as a moderate- to high-radiation diagnostic technique. The improved resolution of CT has permitted the development of new investigations, which may have advantages; compared to conventional radiography, for example, CT angiography avoids the invasive insertion of a catheter. CT Colonography (also known as Virtual Colonoscopy or VC for short) may be as useful as a barium enema for detection of tumors, but may use a lower radiation dose. CT VC is increasingly being used in the UK as a diagnostic test for bowel cancer and can negate the need for a colonoscopy.

The radiation dose for a particular study depends on multiple factors: volume scanned, patient build, number and type of scan sequences, and desired resolution and image quality. In addition, two helical CT scanning parameters that can be adjusted easily and that have a profound effect on radiation dose are tube current and pitch. Computed tomography (CT) scan has been shown to be more accurate than radiographs in evaluating anterior interbody fusion but may still over-read the extent of fusion.

Adverse effects

Cancer

The ionizing radiation in the form of x-rays used in CT scans are energetic enough to create radicals from water molecules that can interact with and damage nearby DNA molecules, or less commonly, directly damage the DNA molecule itself. This damage can come in the form of breaks in the double stranded structure of DNA, or in the base pairs, which if not corrected by cellular repair mechanisms, can lead to cancer.

There is a small increase risk of cancer with CT scans with this risk being slightly larger in children. CT scans involve the use of 10 to 100 times more ionizing radiation than plain X-rays. It is estimated that 0.4% of current cancers in the United States are due to CTs performed in the past and that this may increase to as high as 1.5-2% with 2007 rates of CT usage; however, this estimate is disputed.

These estimates are partly based on similar radiation exposures experienced by those present during the atomic bombexplosions in Japan during the second world war and nuclear industry works. Estimated lifetime cancer mortality risks attributable to the radiation exposure from a CT in a 1-year-old are 0.18% (abdominal) and 0.07% (head) — an order of magnitude higher than for adults — although those figures still represent a small increase in cancer mortality over the background rate. In the United States, of approximately 600,000 abdominal and head CT examinations annually performed in children under the age of 15 years, a rough estimate is that 500 of these individuals might ultimately die from cancer attributable to the CT radiation. The additional risk is still low: 0.35% compared to the background risk of dying from cancer of 23%. However, if these statistics are extrapolated to the current number of CT scans, the additional rise in cancer mortality could be 1.5 to 2%. Furthermore, certain conditions can require children to be exposed to multiple CT scans.

In 2009, a number of studies that further defined the risk of cancer that may be caused by CT scans appeared. One study indicated that radiation by CT scans is often higher and more variable than cited, and each of the 19,500 CT scans that are daily performed in the US is equivalent to 30 to 442 chest X-rays in radiation. It has been estimated that CT radiation exposure will result in 29,000 new cancer cases just from the CT scans performed in 2007. The most common cancers caused by CT are thought to be lung cancer, colon cancer and leukemia, with younger people and women more at risk. These conclusions, however, are criticized by the American College of Radiology (ACR), which maintains that the life expectancy of CT scanned patients is not that of the general population and that the model of calculating cancer is based on total-body radiation exposure and thus faulty.

CT scans can be performed with different settings for lower exposure in children, although these techniques are often not employed. Surveys have suggested that, at the current time, many CT scans are performed unnecessarily. Especially in children, the benefits that stem from their use outweigh the risk in many cases.Studies support informing parents of the risks of pediatric CT scanning.

Contrast

The old radiocontrast agents caused reactions in 1% of cases while the newer lower osmolar agents cause reactions in 0.04% of cases. Adverse reactions to the radiocontrast media caused immediate death in 1 to 3 people per 100,000 administrations of the contrast media.

Clinical studies showed that 17.5% of patients present pseudo-allergic reactions after radiocontrast media injection, with symptoms appearing in 90 sec and disappearing 30 min later. "Moreover, it has been shown that adverse reactions induced by ionic contrast materials are in the range of 4% to 12% while those by nonionic contrast materials are 1% to 3%. Katayama et al., in research with over 300,000 contrast administrations, found the revalence of severe adverse drug reactions was 0.04% for nonionic contrast media and 0.2% for ionic contrast media".

The contrast agent may induce contrast-induced nephropathy. This occurs in 2 – 7% of people who receives these agents with greater risk in those who have preexisting renal insufficiency, preexisting diabetes, or reduced intravascular volume. People with mild kidney impairment are usually advised to ensure full hydration for several hours before and after the injection. For moderate kidney failure, the use of iodinated contrast should be avoided; this may mean using an alternative technique instead of CT. Those with severe renal failure requiring dialysis do not require special precautions, as their kidneys have so little function remaining that any further damage would not be noticeable and the dialysis will remove the contrast agent.

Hair loss

A few cases of temporary hair loss following multiple CTs in a short period of time have been reported.

Typical scan dose

| Examination | Typical effective dose (mSv = mGy for X-rays) |

(millirem) |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Personnel security screening scan | 0.00025 | 0.025 |

| Chest X-ray | 0.02 | 10 |

| Head CT | 1.5-2 | 150 |

| Screening mammography | 3 | 300 |

| Abdomen CT | 5.3 | 530 |

| Chest CT | 5.8-8 | 580 |

| CT colonography (virtual colonoscopy) | 3.6–8.8 | 360–880 |

| Chest, abdomen and pelvis CT | 9.9 | 990 |

| Cardiac CT angiogram | 6.7-13 | 670–1300 |

| Barium enema | 15 | 1500 |

| Neonatal abdominal CT | 20 | 2000 |

The following table include data of typical scan doses, as were observed in a survey of a few CT machines. The data represent an average of the observed values, however the maximal observed values in the survey were about two times higher than the average values. The table include data for a few specific scanning protocols, however other scanning protocols of the same body parts exist, and some of which subject patients to greater radiation. In some studies, the same body part is scanned twice, once without contrast agent, and once with contrast agent, which doubles the stated scan dose.

Radiation dose units

---- The radiation dose reported in the Gray or mGy unit is proportional to the amount energy that the irradiated body part is expected to absorb, and the physical effect (such as double strand breaks) on the cell's chemical bonds by x-ray radiation is proportional to that energy.

---- The volume weighted CT dose index (CTDIvol) is used to report an absorbed dose in the Gray unit, that is proportional to the average of the energy that is absorbed by the body part, since the amount of energy that is absorbed is greater at the skin, and lower at the center of the body part.

---- The Sievert unit is used in the report of the effective dose. The Sievert unit in the context of CT scans, do not correspond to the actual radiation, that the scanned body part absorb, but rather to an other radiation level of an other scenario, in which the whole body is subjected to the other radiation level, and where the other radiation level is of a magnitude, that is estimated to have the same probability to induce cancer, as the CT scan. Thus, as is shown in the table above, the actual radiation that is absorbed by a scanned body part is often much larger than the effective dose disclose.

Note, that even though the stated objective of the effective dose is to report a whole body radiation value, that is proportional to the biological effect of the actual radiation, the effective dose measure the biological effect based on statistical studies of cancer rates in a population, that was exposed to radiation from a nuclear blast, and thus its fulfillment of its objective is questionable, due to the possibility that the biological effect of radiation from a nuclear blast is different, due to the fact that exposure to a nuclear blast during war is a psychologically traumatic event in itself, due to covering only one biological effect, namely cancer, and due to a very limited theoretical understanding.

---- The equivalent dose is the effective dose of a case, in which the whole body would actually be subjected to the same radiation level, and the Sievert unit is used in its report. In the case of non-uniform radiation, or radiation given to only part of the body, which is common for CT examinations, using the local equivalent dose alone would overstate the biological risks to the entire organism.

---- The dose length product (DLP) is the multiplication of the CTDIvol with the length of the portion of the body part that was scanned, and has the units of Gray*Centimeter. It is used, by multiplication with constants, to derive the effective dose, and cancer risk, that correspond to the irradiation of a portion of a body part, and can be used in other calculations, which include the multiplication, that the DLP include.

Image Quality

Artifacts

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Although CT is a relatively accurate test, it is liable to produce artifacts, such as the following:

- Streak artifact

- Streaks are often seen around materials that block most X-rays, such as metal or bone. These streaks can be caused by undersampling, photon starvation, motion, beam hardening, or scatter. This type of artifact commonly occurs in the posterior fossa of the brain, or if there are metal implants. The streaks can be reduced using newer reconstruction techniques.

- Partial volume effect

- This appears as "blurring" over sharp edges. It is due to the scanner being unable to differentiate between a small amount of high-density material (e.g., bone) and a larger amount of lower density (e.g., cartilage). The processor tries to average out the two densities or structures, and information is lost. This can be partially overcome by scanning using thinner slices.

- Ring artifact

- Probably the most common mechanical artifact, the image of one or many "rings" appears within an image. This is usually due to a detector fault.

- Noise artifact

- This appears as graining on the image and is caused by a low signal to noise ratio. This occurs more commonly when a thin slice thickness is used. It can also occur when the power supplied to the X-ray tube is insufficient to penetrate the anatomy.

- Motion artifact

- This is seen as blurring and/or streaking, which is caused by movement of the object being imaged. Motion blurring might be reduced using a new technique called IFT (incompressible flow tomography).

- Windmill

- Streaking appearances can occur when the detectors intersect the reconstruction plane. This can be reduced with filters or a reduction in pitch.

- Beam hardening

- This can give a "cupped appearance". It occurs when there is more attenuation in the center of the object than around the edge. This is easily corrected by filtration and software.

CT Dose vs. Image Quality

An important issue within radiology today is how to reduce the radiation dose during CT examinations without compromising the image quality. In general, higher radiation doses result in higher-resolution images, while lower doses lead to increased image noise and unsharp images. However, increased dosage raises increase the adverse side effects, including the risk of radiation induced cancer — a four-phase abdominal CT gives the same radiation dose as 300 chest x-rays. Several methods that can reduce the exposure to ionizing radiation during a CT scan exist.

- New software technology can significantly reduce the required radiation dose.

- Individualize the examination and adjust the radiation dose to the body type and body organ examined. Different body types and organs require different amounts of radiation.

- Prior to every CT examination, evaluate the appropriateness of the exam whether it is motivated or if another type of examination is more suitable. Higher resolution is not always suitable for any given scenario, such as detection of small pulmonary masses

Prevalence

Usage of CT has increased dramatically over the last two decades. An estimated 72 million scans were performed in the United States in 2007. In Calgary, Canada 12.1% of people who present to the emergency with an urgent complaint received a CT scan, most commonly either of the head or of the abdomen. The percentage who received CT, however, varied markedly by the emergency physician who saw them from 1.8% to 25%. In the emergency department in the United States, CT or MRI imaging is done in 15% of people who present with injuries as of 2007 (up from 6% in 1998).

The increased use of CT scans has been the greatest in two fields: screening of adults (screening CT of the lung in smokers, virtual colonoscopy, CT cardiac screening, and whole-body CT in asymptomatic patients) and CT imaging of children. Shortening of the scanning time to around 1 second, eliminating the strict need for the subject to remain still or be sedated, is one of the main reasons for the large increase in the pediatric population (especially for the diagnosis of appendicitis).

Process

X-ray slice data is generated using an X-ray source that rotates around the object; X-ray sensors are positioned on the opposite side of the circle from the X-ray source. The earliest sensors were scintillation detectors, with photomultiplier tubes excited by (typically) cesium iodide crystals. Cesium iodide was replaced during the 1980s by ion chambers containing high-pressure Xenon gas. These systems were in turn replaced by scintillation systems based on photodiodes instead of photomultipliers and modern scintillation materials with more desirable characteristics. Many data scans are progressively taken as the object is gradually passed through the gantry.

Newer machines with faster computer systems and newer software strategies can process not only individual cross sections but continuously changing cross sections as the gantry, with the object to be imaged slowly and smoothly slid through the X-ray circle. These are called helical or spiral CT machines. Their computer systems integrate the data of the moving individual slices to generate three dimensional volumetric information (3D-CT scan), in turn viewable from multiple different perspectives on attached CT workstation monitors. This type of data acquisition requires enormous processing power, as the data are arriving in a continuous stream and must be processed in real-time.

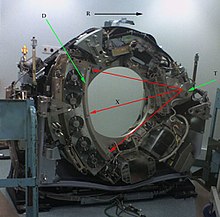

In conventional CT machines, an X-ray tube and detector are physically rotated behind a circular shroud (see the image above right); in the electron beam tomography (EBT), the tube is far larger and higher power to support the high temporal resolution. The electron beam is deflected in a hollow funnel-shaped vacuum chamber. X-rays are generated when the beam hits the stationary target. The detector is also stationary. This arrangement can result in very fast scans, but is extremely expensive.

CT is used in medicine as a diagnostic tool and as a guide for interventional procedures. Sometimes contrast materials such as intravenous iodinated contrast are used. This is useful to highlight structures such as blood vessels that otherwise would be difficult to delineate from their surroundings. Using contrast material can also help to obtain functional information about tissues.

Once the scan data has been acquired, the data must be processed using a form of tomographic reconstruction, which produces a series of cross-sectional images. The most common technique in general use is filtered back projection, which is straightforward to implement and can be computed rapidly. In terms of mathematics, this method is based on the Radon transform. However, this is not the only technique available: the original EMI scanner solved the tomographic reconstruction problem by linear algebra, but this approach was limited by its high computational complexity, especially given the computer technology available at the time. More recently, manufacturers have developed iterative physical model-based expectation-maximization techniques. These techniques are advantageous because they use an internal model of the scanner's physical properties and of the physical laws of X-ray interactions. By contrast, earlier methods have assumed a perfect scanner and highly simplified physics, which leads to a number of artifacts and reduced resolution - the result is images with improved resolution, reduced noise and fewer artifacts, as well as the ability to greatly reduce the radiation dose in certain circumstances. The disadvantage is a very high computational requirement, which is at the limits of practicality for current scan protocols.

Pixels in an image obtained by CT scanning are displayed in terms of relative radiodensity. The pixel itself is displayed according to the mean attenuation of the tissue(s) that it corresponds to on a scale from +3071 (most attenuating) to -1024 (least attenuating) on the Hounsfield scale. Pixel is a two dimensional unit based on the matrix size and the field of view. When the CT slice thickness is also factored in, the unit is known as a Voxel, which is a three-dimensional unit. The phenomenon that one part of the detector cannot differentiate between different tissues is called the "Partial Volume Effect". That means that a big amount of cartilage and a thin layer of compact bone can cause the same attenuation in a voxel as hyperdense cartilage alone. Water has an attenuation of 0 Hounsfield units (HU), while air is -1000 HU, cancellous bone is typically +400 HU, cranial bone can reach 2000 HU or more (os temporale) and can cause artifacts. The attenuation of metallic implants depends on atomic number of the element used: Titanium usually has an amount of +1000 HU, iron steel can completely extinguish the X-ray and is, therefore, responsible for well-known line-artifacts in computed tomograms. Artifacts are caused by abrupt transitions between low- and high-density materials, which results in data values that exceed the dynamic range of the processing electronics.

Contrast mediums used for X-ray CT, as well as for plain film X-ray, are called radiocontrasts. Radiocontrasts for X-ray CT are, in general, iodine-based. Often, images are taken both with and without radiocontrast. CT images are called precontrast or native-phase images before any radiocontrast has been administrated, and postcontrast after radiocontrast administration.

Three-dimensional reconstruction

Because contemporary CT scanners offer isotropic or near isotropic, resolution, display of images does not need to be restricted to the conventional axial images. Instead, it is possible for a software program to build a volume by "stacking" the individual slices one on top of the other. The program may then display the volume in an alternative manner.

Multiplanar reconstruction

Multiplanar reconstruction (MPR) is the simplest method of reconstruction. A volume is built by stacking the axial slices. The software then cuts slices through the volume in a different plane (usually orthogonal). As an option, a special projection method, such as maximum-intensity projection (MIP) or minimum-intensity projection (mIP), can be used to build the reconstructed slices.

MPR is frequently used for examining the spine. Axial images through the spine will only show one vertebral body at a time and cannot reliably show the intervertebral discs. By reformatting the volume, it becomes much easier to visualise the position of one vertebral body in relation to the others.

Modern software allows reconstruction in non-orthogonal (oblique) planes so that the optimal plane can be chosen to display an anatomical structure. This may be particularly useful for visualising the structure of the bronchi as these do not lie orthogonal to the direction of the scan.

For vascular imaging, curved-plane reconstruction can be performed. This allows bends in a vessel to be "straightened" so that the entire length can be visualised on one image, or a short series of images. Once a vessel has been "straightened" in this way, quantitative measurements of length and cross sectional area can be made, so that surgery or interventional treatment can be planned.

MIP reconstructions enhance areas of high radiodensity, and so are useful for angiographic studies. MIP reconstructions tend to enhance air spaces so are useful for assessing lung structure.

3D rendering techniques

Surface rendering

A threshold value of radiodensity is set by the operator (e.g., a level that corresponds to bone). From this, a three-dimensional model can be constructed using edge detection image processing algorithms and displayed on screen. Multiple models can be constructed from various thresholds, allowing different colors to represent each anatomical component such as bone, muscle, and cartilage. However, the interior structure of each element is not visible in this mode of operation.

Volume rendering

Surface rendering is limited in that it will display only surfaces that meet a threshold density, and will display only the surface that is closest to the imaginary viewer. In volume rendering, transparency and colors are used to allow a better representation of the volume to be shown in a single image. For example, the bones of the pelvis could be displayed as semi-transparent, so that, even at an oblique angle, one part of the image does not conceal another.

Image segmentation

Main article: Segmentation (image processing)Where different structures have similar radiodensity, it can become impossible to separate them simply by adjusting volume rendering parameters. The solution is called segmentation, a manual or automatic procedure that can remove the unwanted structures from the image.

Industrial use

Industrial CT Scanning (industrial computed tomography) is a process which utilizes x-ray equipment to produce 3D representations of components both externally and internally. Industrial CT scanning has been utilized in many areas of industry for internal inspection of components. Some of the key uses for CT scanning have been flaw detection, failure analysis, metrology, assembly analysis and reverse engineering applications

Etymology

The word "tomography" is derived from the Greek tomos (slice) and graphein (to write). Computed tomography was originally known as the "EMI scan" as it was developed in the early 1970's at a research branch of EMI, a company best known today for its music and recording business. It was later known as computed axial tomography (CAT or CT scan) and body section röntgenography.

Although the term "computed tomography" could be used to describe positron emission tomography and single photon emission computed tomography, in practice it usually refers to the computation of tomography from X-ray images, especially in older medical literature and smaller medical facilities.

In MeSH, "computed axial tomography" was used from 1977–79, but the current indexing explicitly includes "X-ray" in the title.

Types of CT Machine

Spinning tube, commonly called spiral CT, or helical CT in which an entire X-ray tube is spun around the central axis of the area being scanned. These are the dominant type of scanners on the market because they have been manufactured longer and offer lower cost of production and purchase. The main limitation of this type is the bulk and inertia of the equipment (X-ray tube assembly and detector array on the opposite side of the circle) which limits the speed at which the equipment can spin.

Electron beam tomography is a specific form of CT in which a large enough X-ray tube is constructed so that only the path of the electrons, traveling between the cathode and anode of the X-ray tube, are spun using deflection coils. This type has a major advantage since sweep speeds can be much faster, allowing for less blurry imaging of moving structures, such as the heart and arteries. However, far fewer CTs of this design have been produced, mainly due to the higher cost associated with building a much larger X-ray tube and detector array.

History

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In the early 1900s, the Italian radiologist Alessandro Vallebona proposed a method to represent a single slice of the body on the radiographic film. This method was known as tomography. The idea is based on simple principles of projective geometry: moving synchronously and in opposite directions the X-ray tube and the film, which are connected together by a rod whose pivot point is the focus; the image created by the points on the focal plane appears sharper, while the images of the other points annihilate as noise. This is only marginally effective, as blurring occurs in only the "x" plane. There are also more complex devices that can move in more than one plane and perform more effective blurring.

The mathematical theory behind the Tomographic reconstruction dates back to 1917 where the invention of Radon Transform by an Austrian mathematician Johann Radon. He showed mathematically that a function could be reconstructed from an infinite set of its projections. In 1937, a Polish mathematician, named Stefan Kaczmarz, developed a method to find an approximate solution to a large system of linear algebraic equations. This led the foundation to another powerful reconstruction method called "Algebraic Reconstruction Technique (ART)" which was later adapted by Sir Godfrey Hounsfield as the image reconstruction mechanism in his famous invention, the first commercial CT scanner. In 1956, Ronald N. Bracewell used a method similar to Radon Transform to reconstruct a map of solar radiation from a set of solar radiation measurements. In 1959, William Oldendorf, a UCLA neurologist and senior medical investigator at the West Los Angeles Veterans Administration hospital, conceived an idea for "scanning a head through a transmitted beam of X-rays, and being able to reconstruct the radiodensity patterns of a plane through the head" after watching an automated apparatus built to reject frost-bitten fruit by detecting dehydrated portions. In 1961, he built a prototype in which an X-ray source and a mechanically coupled detector rotated around the object to be imaged. By reconstructing the image, this instrument could get an X-ray picture of a nail surrounded by a circle of other nails, which made it impossible to X-ray from any single angle. In his landmark paper, published in 1961, he described the basic concept later used by Allan McLeod Cormack to develop the mathematics behind computerized tomography. In October, 1963 Oldendorf received a U.S. patent for a "radiant energy apparatus for investigating selected areas of interior objects obscured by dense material," Oldendorf shared the 1975 Lasker award with Hounsfield for that discovery.

Tomography has been one of the pillars of radiologic diagnostics until the late 1970s, when the availability of minicomputers and of the transverse axial scanning method – this last due to the work of Godfrey Hounsfield and South African-born Allan McLeod Cormack – gradually supplanted it as the modality of CT. In terms of mathematics, the method is based upon the use of the Radon Transform. But as Cormack remembered later, he had to find the solution himself since it was only in 1972 that he learned of the work of Radon, by chance.

The first commercially viable CT scanner was invented by Sir Godfrey Hounsfield in Hayes, United Kingdom, at EMI Central Research Laboratories using X-rays. Hounsfield conceived his idea in 1967. The first EMI-Scanner was installed in Atkinson Morley Hospital in Wimbledon, England, and the first patient brain-scan was done on 1 October 1971. It was publicly announced in 1972.

The original 1971 prototype took 160 parallel readings through 180 angles, each 1° apart, with each scan taking a little over 5 minutes. The images from these scans took 2.5 hours to be processed by algebraic reconstruction techniques on a large computer. The scanner had a single photomultiplier detector, and operated on the Translate/Rotate principle.

It has been claimed that thanks to the success of The Beatles, EMI could fund research and build early models for medical use. The first production X-ray CT machine (in fact called the "EMI-Scanner") was limited to making tomographic sections of the brain, but acquired the image data in about 4 minutes (scanning two adjacent slices), and the computation time (using a Data General Nova minicomputer) was about 7 minutes per picture. This scanner required the use of a water-filled Perspex tank with a pre-shaped rubber "head-cap" at the front, which enclosed the patient's head. The water-tank was used to reduce the dynamic range of the radiation reaching the detectors (between scanning outside the head compared with scanning through the bone of the skull). The images were relatively low resolution, being composed of a matrix of only 80 x 80 pixels.

In the U.S., the first installation was at the Mayo Clinic. As a tribute to the impact of this system on medical imaging the Mayo Clinic has an EMI scanner on display in the Radiology Department. Allan McLeod Cormack of Tufts University in Massachusetts independently invented a similar process, and both Hounsfield and Cormack shared the 1979 Nobel Prize in Medicine.

The first CT system that could make images of any part of the body and did not require the "water tank" was the ACTA (Automatic Computerized Transverse Axial) scanner designed by Robert S. Ledley, DDS, at Georgetown University. This machine had 30 photomultiplier tubes as detectors and completed a scan in only 9 translate/rotate cycles, much faster than the EMI-scanner. It used a DEC PDP11/34 minicomputer both to operate the servo-mechanisms and to acquire and process the images. The Pfizer drug company acquired the prototype from the university, along with rights to manufacture it. Pfizer then began making copies of the prototype, calling it the "200FS" (FS meaning Fast Scan), which were selling as fast as they could make them. This unit produced images in a 256×256 matrix, with much better definition than the EMI-Scanner's 80×80.

Since the first CT scanner, CT technology has vastly improved. Improvements in speed, slice count, and image quality have been the major focus primarily for cardiac imaging. Scanners now produce images much faster and with higher resolution enabling doctors to diagnose patients more accurately and perform medical procedures with greater precision. In the late 90's CT scanners broke into two major groups, "Fixed CT" and "Portable CT". "Fixed CT Scanners" are large, require a dedicated power supply, electrical closet, HVAC system, a separate workstation room, and a large lead lined room. "Fixed CT Scanners" can also be mounted inside large tractor trailers and driven from site to site and are known as "Mobile CT Scanners". "Portable CT Scanners" are light weight, small, and mounted on wheels. These scanners often have built-in lead shielding and run off of batteries or standard wall power.

Previous studies

Pneumoencephalography Study for brain was quickly replaced by CT. A form of tomography can be performed by moving the X-ray source and detector during an exposure. Anatomy at the target level remains sharp, while structures at different levels are blurred. By varying the extent and path of motion, a variety of effects can be obtained, with variable depth of field and different degrees of blurring of "out of plane" structures. Although largely obsolete, conventional tomography is still used in specific situations such as dental imaging (orthopantomography) or in intravenous urography.

See also

- Tomosynthesis

- Virtopsy

- Xenon-enhanced CT scanning

- X-ray microtomography

- MRI versus CT

- Biological effects of ionizing radiation

- DNA damage

- Harmful mutations

- Radiation induced cognitive decline

- Radiation therapy

- Dosimetry

References

- "computed tomography—Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- ^ Herman, G. T., Fundamentals of computerized tomography: Image reconstruction from projection, 2nd edition, Springer, 2009

- ^ Smith-Bindman R, Lipson J, Marcus R; et al. (2009). "Radiation dose associated with common computed tomography examinations and the associated lifetime attributable risk of cancer". Arch. Intern. Med. 169 (22): 2078–86. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.427. PMID 20008690.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Berrington de González A, Mahesh M, Kim KP; et al. (2009). "Projected cancer risks from computed tomographic scans performed in the United States in 2007". Arch. Intern. Med. 169 (22): 2071–7. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.440. PMID 20008689.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brenner DJ, Hall EJ (2007). "Computed tomography--an increasing source of radiation exposure". N. Engl. J. Med. 357 (22): 2277–84. doi:10.1056/NEJMra072149. PMID 18046031.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Tubiana M (2008). "Comment on Computed Tomography and Radiation Exposure". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (8): 852–3. doi:10.1056/NEJMc073513. PMID 18287609.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "Ankle Fractures". orthoinfo.aaos.org. American Association of Orthopedic Surgeons. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- Buckwalter, Kenneth A.; et al. (11 September 2000). "Musculoskeletal Imaging with Multislice CT". ajronline.org. American Journal of Roentgenology. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Brian R. Subach M.D., F.A.C.S et. al. "Reliability and accuracy of fine-cut computed tomography scans to determine the status of anterior interbody fusions with metallic cages"

- Hall, EJ (2008 May). "Cancer risks from diagnostic radiology". The British journal of radiology. 81 (965): 362–78. PMID 18440940.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Brenner, DJ (2010 Jan-Mar). "Should we be concerned about the rapid increase in CT usage?". Reviews on environmental health. 25 (1): 63–8. PMID 20429161.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Hasebroock, KM (2009 Apr). "Toxicity of MRI and CT contrast agents". Expert opinion on drug metabolism & toxicology. 5 (4): 403–16. PMID 19368492.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Brenner DJ, Hall EJ (2007). "Computed tomography--an increasing source of radiation exposure". N. Engl. J. Med. 357 (22): 2277–84. doi:10.1056/NEJMra072149. PMID 18046031.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Tubiana M (2008). "Comment on Computed Tomography and Radiation Exposure". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (8): 852–3. doi:10.1056/NEJMc073513. PMID 18287609.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Brenner DJ, Hall EJ (2007). "Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure". N. Engl. J. Med. 357 (22): 2277–84. doi:10.1056/NEJMra072149. PMID 18046031.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Brenner D, Elliston C, Hall E, Berdon W (2001). "Estimated risks of radiation-induced fatal cancer from pediatric CT". AJR Am J Roentgenol. 176 (2): 289–96. PMID 11159059.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Roxanne Nelson (December 17, 2009). "Thousands of New Cancers Predicted Due to Increased Use of CT". Medscape. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- Semelka, RC; Armao, DM; Elias, J, Jr.; Huda, W. (2007). "Imaging strategies to reduce the risk of radiation in CT studies, including selective substitution with MRI". J Magn Reson Imaging. 25 (5): 900–9. doi:10.1002/jmri.20895. PMID 17457809.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Larson DB, Rader SB, Forman HP, Fenton LZ (2007). "Informing parents about CT radiation exposure in children: it's OK to tell them". AJR Am J Roentgenol. 189 (2): 271–5. doi:10.2214/AJR.07.2248. PMID 17646450.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Drain, KL (2001). "Preventing and managing drug-induced anaphylaxis". Drug safety : an international journal of medical toxicology and drug experience. 24 (11): 843–53. PMID 11665871.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - that induce pseudo-allergic reaction.

- ^ that induce pseudo-allergic reaction.

- Imanishi, Y (2005 Jan). "Radiation-induced temporary hair loss as a radiation damage only occurring in patients who had the combination of MDCT and DSA". European radiology. 15 (1): 41–6. PMID 15351903.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "What are the Radiation Risks from CT?". Food and Drug Administration. 2009.

- "to University of California - San Francisco Regarding Their Letter of Concern, October 12, 2010, US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), October 12, 2010

- ^ Shrimpton, P.C; Miller, H.C; Lewis, M.A; Dunn, M. Doses from Computed Tomography (CT) examinations in the UK -2003 Review

- "Radiation Exposure during Cardiac CT: Effective Doses at Multi–Detector Row CT and Electron-Beam CT". Radiology.rsnajnls.org. 2002-11-21. Retrieved 2009-10-13.

- "Our shuttle mode CTP scanning protocol described above results in a radiation exposure, the volumetric CT dose index (CTDIvol), of 349 mGy."

- The Measurement, Reporting, and Management of Radiation Dose in CT "It is a single dose parameter that reflects the risk of a nonuniform exposure in terms of an equivalent whole-body exposure."

- Boas FE and Fleischmann D (2011). "Evaluation of Two Iterative Techniques for Reducing Metal Artifacts in Computed Tomography". Radiology. 259 (3): 894–902. doi:10.1148/radiol.11101782. PMID 21357521.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - J. Nemirovsky, A. Lifshitz, and I. Be’erya (2011). "Tomographic reconstruction of incompressible flow". AIP Rev. Sci. Instrum. 82 (5). Bibcode:2011RScI...82e5115N. doi:10.1063/1.3590934.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Simpson, Graham (2009). "Thoracic computed tomography: principles and practice" (PDF). Australian Prescriber, 32:4. Retrieved September 25, 2009.

- Andrew Skelly (Aug 3 2010). "CT ordering all over the map". The Medical Post.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Korley FK, Pham JC, Kirsch TD (2010). "Use of advanced radiology during visits to US emergency departments for injury-related conditions, 1998-2007". JAMA. 304 (13): 1465–71. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1408. PMID 20924012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Contrast agent for radiotherapy CT (computed tomography) scans. Patient Information Series No. 11 at University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Last reviewed: October 2009

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1080/028418500127345479, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1080/028418500127345479instead. - Udupa, J.K. and Herman, G. T., 3D Imaging in Medicine, 2nd Edition, CRC Press, 2000

- Tomography,+X-Ray+Computed at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Radon J., Uber die Bestimmung von Funktionen durch ihre Integralwerte Langs Gewisser Mannigfaltigkeiten (English translation: On the determination of functions from their integrals along certain manifolds). Ber. Saechsische Akad. Wiss. 1917;29: 262.

- Radon J., Translated by Parks PC., On the determination of functions from their integrals along certain manifolds. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 1993;MI-5: 170-6.

- Hornich H., Translated by Parks PC. A Tribute to Johann Radon. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 1986;5(4):169-9.

- Kaczmarz, S., Angenäherte Auflösung von Systemen linearer Gleichungen. Bulletin International de l'Académie Polonaise des Sciences et des Lettres. Classe des Sciences Mathématiques et Naturelles. Série A, Sciences Mathématiques. 1937;35: 355–7.

- Kaczmarz S., Approximate solution of system of linear equations. Int. J. Control. 1993; 57-9.

- Bracewell RN., . Aust. J. Phys. 1956;9: 198-217.

- Oldendorf WH. Isolated flying spot detection of radiodensity discontinuities--displaying the internal structural pattern of a complex object. Ire Trans Biomed Electron. 1961 Jan;BME-8:68-72.

- Oldendorf WH. The quest for an image of brain: a brief historical and technical review of brain imaging techniques. Neurology. 1978 Jun;28(6):517-33.

- Allen M.Cormack: My Connection with the Radon Transform, in: 75 Years of Radon Transform, S. Gindikin and P. Michor, eds., International Press Incorporated (1994), pp. 32 - 35, ISBN 1-57146-008-X

- Richmond, Caroline (September 18, 2004). "Obituary—Sir Godfrey Hounsfield". BMJ. 2004:329:687 (18 September 2004). London, UK: BMJ Group. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ BECKMANN, E. C. (2006). "CT scanning the early days". TheBritish Journal of Radiology. 79 (937): 5–8. doi:10.1259/bjr/29444122. PMID 16421398.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "The Beatles greatest gift... is to science". Whittington Hospital NHS Trust. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- Filler, AG (2009): The history, development, and impact of computed imaging in neurological diagnosis and neurosurgery: CT, MRI, DTI: Nature Precedings doi:10.1038/npre.2009.3267.5.

- Novelline, Robert. Squire's Fundamentals of Radiology. Harvard University Press. 5th edition. 1997. ISBN 0-674-83339-2.

External links

| This article's use of external links may not follow Misplaced Pages's policies or guidelines. Please improve this article by removing excessive or inappropriate external links, and converting useful links where appropriate into footnote references. (February 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- CTisus: Information on body CT (Computed tomography) including a 3D vascular atlas with volume rendering, spiral CT protocols, and teaching files

- CT Cases, Imaging cases of medical interest - a free tool for specialists by MD Aris Babis (Athens, Greece) and Dimitris Sioutis (Bologna, Italy).

- Open-source computed tomography simulator with educational tracing displays

- idoimaging.com: Free software for viewing CT and other medical imaging files

- CT Artefacts by David Platten

- DigiMorph A library of 3D imagery based on CT scans of the internal and external structure of living and extinct plants and animals.

- Radiation Risk Calculator Calculate cancer risk from CT scans and xrays.

- CT scanner video - gantry

- CT in your clinical practice by Gregory J. Kohs and Joel Legunn.

- Video documentary of patient getting a CT Scan

- Atlas of Radiological Images on atlas.mudr.org. Hundreds of imaging cases and thousands of radiological images sorted by method, topography, organs, with short description.