| Revision as of 20:45, 4 March 2013 edit129.116.88.72 (talk) →Achievements← Previous edit | Revision as of 15:35, 5 March 2013 edit undoIzhar alam khan (talk | contribs)2 editsNo edit summaryTag: blankingNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| |date=March 2011}} | |||

| {{Redirect|The Shah|other uses|Shah}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=November 2012}} | |||

| {{Infobox royalty | |||

| | name = Mohammad Reza Shah | |||

| | image = Shah of iran.png | |||

| | image_size = 220px | |||

| | caption = Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi in 1973 | |||

| | succession = ] | |||

| | reign = 26 September 1941 – 11 February 1979 | |||

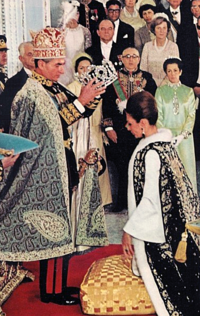

| | coronation = 26 October 1967 | |||

| | predecessor = ] | |||

| | successor = ''Title abolished'' | |||

| | succession1 = ] | |||

| | reign1 = 15 September 1965 – 11 February 1979 | |||

| | predecessor1 = ''Title created'' | |||

| | successor1 = ''Title abolished'' | |||

| | succession2 = ] | |||

| | reign2 = 26 September 1941 – 27 July 1980 | |||

| | reign-type2 = Tenure | |||

| | predecessor2 = ] | |||

| | successor2 = ] | |||

| | issue = ]<br/>]<br/>]<br/>]<br/>] | |||

| | full name = {{lang-en|Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi}}<br/>{{lang-fa|محمد رضا شاه پهلوی}} | |||

| | spouse = ]<br/><small>(m.1939; div. 1948)</small><br/>]<br/><small>(m.1951; div. 1958)</small><br/>]<br/><small>(m.1959; wid.1980)</small> | |||

| | house = ] | |||

| | father = ] | |||

| | mother = ] | |||

| | birth_date = {{Birth date|1919|10|26|df=y}} | |||

| | birth_place = ], ] | |||

| | death_date = {{Death date and age|1980|7|27|1919|10|16|df=y}} | |||

| | death_place = ], ] | |||

| | place of burial = ], Cairo, Egypt | |||

| | religion = ] | |||

| | signature = Mohammadreza pahlavi signature.svg | |||

| }} | |||

| {{infobox hrhstyles | |||

| | image = ] | |||

| | royal name = Mohammad Reza Shah of Iran | |||

| | dipstyle = ] | |||

| | offstyle = Your Imperial Majesty | |||

| | altstyle = Sir | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Contains Perso-Arabic text}} | |||

| '''Mohammad Rezā Shāh Pahlavī''' (]: محمد رضا شاه پهلوی, {{IPA-fa|mohæmˈmæd reˈzɒː ˈʃɒːhe pæhlæˈviː|}}; 26 October 1919 – 27 July 1980) was the last ] (king) of ] from 16 September 1941 until his overthrow by the ] on 11 February 1979. He was the second and last monarch of the ] of the Iranian monarchy. Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi held several titles: His Imperial Majesty, Shahanshah (King of Kings,<ref>D. N. MacKenzie. A Concise Pahlavi Dictionary. Routledge Curzon, 2005.</ref> Emperor), ] (Light of the ]s) and Bozorg Arteshtārān (Head of the Warriors,<ref>M. Mo'in. An Intermediate Persian Dictionary. Six Volumes. Amir Kabir Publications, 1992.</ref> ]: بزرگ ارتشتاران). | |||

| Mohammad Reza came to power during ] after an ] forced the abdication of his father ]. During Mohammad Reza's reign, the Iranian oil industry was briefly ] under Prime Minister ] before a US-backed ] overturned the regime and brought back foreign oil firms,<ref>All the Shah's Men, Stephen Kinzer, p. 195–196.</ref> and Iran marked the anniversary of ] since the founding of the ] by ]. As ruler, he introduced the ], a series of economic, social and political reforms with the stated intention of transforming Iran into a global power and modernizing the nation by nationalizing industries and granting women suffrage. | |||

| A secular Muslim himself, Mohammad Reza gradually lost support from the ] clergy of Iran, particularly due to his strong policy of ], secularization, conflict with the traditional class of merchants known as ]i<!--no article yet for bazaari, a worker in a bazaar-->, and recognition of ]. Various additional controversial policies were enacted, including the banning of the ] ], and a general suppression of political dissent by Iran's ], ]. According to official statistics, Iran had as many as 2,200 ]s in 1978, a number which multiplied rapidly as a result of the revolution.<ref>. ]. Retrieved 26 March 2012.</ref> | |||

| Several other factors contributed to strong opposition to the Shah among certain groups within Iran, the most notable of which were the ] against Mosaddegh in 1953, clashes with ], and increased communist activity. By 1979, political unrest had transformed into a revolution which, on 16 January, forced the Shah to leave Iran. Soon thereafter, the Iranian monarchy was formally abolished, and Iran was declared an ] led by ] ]. Facing likely ] should he return to Iran, he died in exile in ], whose President, ], had granted him ]. | |||

| ==Early life== | |||

| ] with Mehrpour ] (second from right) in Switzerland.]] | |||

| Born in ] to ] and his second wife, ], Mohammad Reza was the eldest son of the first Shah of the ], and the third of his eleven children. He was born with a twin sister, ]. However, Shams, Mohammad Reza, Ashraf, ], and their older half-sister, Fatemeh, were born as non-royals, as their father did not become Shah until 1925. Nevertheless, Reza Shah was always convinced that his sudden quirk of good fortune had commenced in 1919 with the birth of his son who was dubbed ''khoshghadam'' (bird of good omen).<ref>Fereydoun Hoveyda, The Shah and the Ayatollah: Iranian Mythology and Islamic Revolution (Westport: Praeger, 2003) p. 5; and Ali Dashti, ''Panjah va Panj'' ("Fifty Five") (Los Angeles: Dehkhoda, 1381) page 13</ref> | |||

| By the time the Mohammad Reza Shah turned 11, ] deferred to the recommendation of ] to dispatch his son to ], a Swiss boarding school for further studies. He would be the first Iranian prince in line for the throne to be sent abroad to attain a foreign education and remained there for the next four years before returning to obtain his high school diploma in Iran in 1936. After returning to the country, the Crown Prince was registered at the local ] in Tehran where he remained enrolled until 1938. | |||

| ==Early reign== | |||

| {{refimprove section|date=February 2011}} | |||

| ===Deposition of his father=== | |||

| ] was forced to abdicate in favor of his son.]] | |||

| {{Main|Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran|Persian Corridor}} | |||

| In the midst of ] in 1941, ] began ] and invaded the ], breaking the ]. This had a major impact on Iran, which had declared neutrality in the conflict. | |||

| Later that year British and Soviet forces occupied Iran in a military invasion, forcing Reza Shah to abdicate. Prince Mohammad Reza replaced him on the throne on 16 September 1941. Subsequent to his succession as Shah, Iran became a major conduit for British and, later, American aid to the USSR during the war. This massive supply effort became known as the ], an involvement that would continue to grow until the successful revolution against the Iranian monarchy in 1979. | |||

| Much of the credit for orchestrating a smooth transition from Reza Shah to his son was due to the efforts of Mohammad Ali Foroughi. Suffering from ], a frail Foroughi was summoned to the Palace and appointed Prime Minister when Reza Shah feared the end of the Pahlavi dynasty once the Allies invaded Iran in 1941. When Reza Shah sought his assistance to ensure that the Allies would not put an end to the Pahlavi dynasty, Foroughi put aside his adverse personal sentiments for having been politically sidelined since 1935. The Crown Prince confided in amazement to the British Minister that Foroughi "hardly expected any son of Reza Shah to be a civilized human being", but Foroughi successfully derailed thoughts by the ] to undertake a more drastic change in the political infrastructure of Iran.{{Citation needed|date=March 2011}} | |||

| A general amnesty was issued two days after Mohammad Reza Shah's accession to the throne on 19 September 1941. All political personalities who had suffered disgrace during his father's reign were rehabilitated, and the forced unveiling policy inaugurated by his father in 1935 was overturned. Despite the young Shah's enlightened decisions, the British Minister in Tehran reported to London that "the young Shah received a fairly spontaneous welcome on his first public experience, possibly rather to relief at the disappearance of his father than to public affection for himself." | A general amnesty was issued two days after Mohammad Reza Shah's accession to the throne on 19 September 1941. All political personalities who had suffered disgrace during his father's reign were rehabilitated, and the forced unveiling policy inaugurated by his father in 1935 was overturned. Despite the young Shah's enlightened decisions, the British Minister in Tehran reported to London that "the young Shah received a fairly spontaneous welcome on his first public experience, possibly rather to relief at the disappearance of his father than to public affection for himself." | ||

| Despite his public professions of admiration in later years, Mohammad Reza Shah had serious misgivings about not only the coarse and roughshod political means adopted by his father, but also his unsophisticated approach to the affairs of the state. {{Citation needed|date=March 2011}} The young Shah possessed a decidedly more refined temperament, and among the unsavory developments that "would haunt him when he was king" were the political disgrace brought by his father on ]; the dismissal of Foroughi by the mid-1930s; and ]'s decision to commit suicide in 1937.<ref>Gholam Reza Afghami, The Life and Times of the Shah (2009), pages 34–35</ref> An even more significant decision that cast a long shadow was the disastrous and one-sided agreement his father had negotiated with APOC in 1933, one which compromised the country's ability to receive more favorable returns from oil extracted from the country. | |||

| ===Oil nationalization and the 1953 coup=== | ===Oil nationalization and the 1953 coup=== | ||

| Line 77: | Line 8: | ||

| {{Main|1953 Iranian coup d'état}} | {{Main|1953 Iranian coup d'état}} | ||

| By the early 1950s, the political crisis brewing in Iran commanded the attention of British and American policy leaders. In 1951, Dr. Mosaddegh was appointed Prime Minister and committed to nationalizing the Iranian petroleum industry controlled by the Anglo-Persian Oil Company. Under the leadership of the democratically elected ] movement of Dr. ], the Iranian parliament unanimously voted to nationalize the oil industry – thus shutting out the immensely profitable ] (AIOC), which was a pillar of Britain's economy and provided it political clout in the region. | |||

| ] in Washington, c. 18 November 1949]] | |||

| At the start of the confrontation, American political sympathy was forthcoming from the ]. In particular, Mossadegh was buoyed by the advice and counsel he was receiving from American Ambassador in Tehran, | |||

| ]. However, eventually American decision-makers lost their patience, and by the time a ] Administration came to office fears that communists were poised to overthrow the government became an all consuming concern (these concerns were later dismissed as "paranoid" in retrospective commentary on the coup from US government officials). Shortly prior to the ] in the US, the British government invited ] agent ] to London to propose collaboration on a secret plan, code-named "Operation Ajax", to force Mosaddegh from office.<ref>Kermit Roosevelt, Counter Coup, New York, 1979</ref> This would be the first of three "regime change" operations led by ] (the other two being the successful CIA-instigated ] and the failed ] of Cuba). | |||

| Under the direction of Kermit Roosevelt, Jr., a senior ] (CIA) officer and grandson of former U.S. President ], the American CIA and British ] (SIS) funded and led a ] to depose Mosaddegh with the help of military forces disloyal to the democratically elected government. Referred to as ].<ref>{{cite news|first=James|last=Risen|title=Secrets of History: The C.I.A. in Iran|publisher=The New York Times|year=2000|url= http://www.nytimes.com/library/world/mideast/041600iran-cia-index.html|accessdate=30 March 2007}}</ref> The plot hinged on orders signed by the Shah to dismiss Mosaddegh as prime minister and replace him with General ] – a choice agreed on by the British and Americans. | |||

| Despite the high-level cois claim, asserting that he had been the target of various assassination attempts by Soviet agents for many years. | |||

| Despite the high-level coordination and planning, the coup initially failed, causing the Shah to flee to ], then ]. After a brief exile in ], the Shah returned to Iran, this time through a successful second attempt at a coup. A deposed Mosaddegh was arrested and tried. The King intervened and ] the sentence to one and a half years. Zahedi was installed to succeed Mosaddegh.<ref name = "Pollack 72–3">Pollack, The Persian Puzzle (2005), pp. 73–2</ref> | |||

| Before the first attempted coup, the American Embassy in Tehran reported that Mosaddegh's popular support remained robust. The Prime Minister requested direct control of the army from the ]. Given the situation, alongside the strong personal support of ] leader ] and Prime Minister ] for covert action, the American government gave the go-ahead to a committee, attended by the Secretary of State ], ] ], Kermit Roosevelt, Henderson, and ] ]. Kermit Roosevelt returned to Iran on 13 July 1953, and again on 1 August 1953, in his first meeting with the Shah. A car picked him up at midnight and drove him to the palace. He lay down on the seat and covered himself with a blanket as guards waved his driver through the gates. The Shah got into the car and Roosevelt explained the mission. The CIA bribed him with $1 million in Iranian currency, which Roosevelt had stored in a large safe – a bulky cache, given the exchange rate at the time of 1,000 rial to 15 dollars.<ref>Robert Graham, Iran: The Illusion of Power, p. 66</ref> | |||

| The Communists staged massive demonstrations to hijack Mosaddegh's initiatives. The United States had actively plotted against him. On 16 August 1953, the right wing of the Army attacked. Armed with an order by the Shah, it appointed General ] as prime minister. A coalition of mobs and retired officers close to the Palace executed this coup d'état. They failed dismally and the Shah fled the country in humiliating haste. Even '']'', the nation's largest daily newspaper, and its pro-Shah publisher, Abbas Masudi, were against him.<ref>New York Times, 23 July 1953, 1:5</ref> | |||

| During the following two days, the Communists turned against Mosaddegh. Opposition against him grew tremendously. They roamed Tehran raising red flags and pulling down statues of Reza Shah. This was rejected by conservative clerics like ] and ] leaders like ], who sided with the Shah. On 18 August 1953, Mosaddegh defended the Government against this new attack. Tudeh Partisans were clubbed and dispersed.<ref>New York Times, 19 August 1953, 1:4, p. 5</ref> | |||

| The Tudeh had no choice but to accept defeat. In the meantime, according to the CIA plot, Zahedi appealed to the military, and claimed to be the legitimate prime minister and charged Mosaddegh with staging a coup by ignoring the Shah's decree. Zahedi's son Ardeshir acted as the contact between the CIA and his father. On 19 August 1953, pro-Shah partisans – bribed with $100,000 in CIA funds – finally appeared and marched out of south Tehran into the city center, where others joined in. Gangs with clubs, knives, and rocks controlled the streets, overturning Tudeh trucks and beating up anti-Shah activists. As Roosevelt was congratulating Zahedi in the basement of his hiding place, the new Prime Minister's mobs burst in and carried him upstairs on their shoulders. That evening, Henderson suggested to Ardashir that Mosaddegh not be harmed. Roosevelt gave Zahedi US$900,000 left from Operation Ajax funds.{{Citation needed|date=February 2013}}<!-- The whole paragraph --> | |||

| U.S. actions further solidified sentiments that the West was a meddlesome influence in Iranian politics. In the year 2000, reflecting on this notion, U.S. Secretary of State ] stated: | |||

| <blockquote>"In 1953 the United States played a significant role in orchestrating the overthrow of Iran's popular Prime Minister, Mohammed Mosaddegh. The Eisenhower Administration believed its actions were justified for strategic reasons; but the coup was clearly a setback for Iran's political development. And it is easy to see now why many Iranians continue to resent this intervention by America in their internal affairs."<ref>, 17 March 2000 Albright remarks on American-Iran Relations</ref></blockquote> | |||

| <!-- Commented out because image was deleted: ] -->''' | |||

| The Shah returned to power, but never extended the elite status of the court to the technocrats and intellectuals who emerged from Iranian and Western universities. Indeed, his system irritated the new classes, for they were barred from partaking in real power.<ref>R.W. Cottam, Nationalism in Iran</ref> | |||

| ===Assassination attempts=== | |||

| Mohammad Reza Shah was the target of at least two unsuccessful assassination attempts. On 4 February 1949, the Shah attended an annual ceremony to commemorate the founding of ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://geocities.com/ali_vazirsafavi/IranLing.htm|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20091027055554/http://geocities.com/ali_vazirsafavi/IranLing.htm|archivedate=27 October 2009|title=Ali Vazir Safavi|publisher=Web Archive|date=27 October 2009|accessdate=18 June 2011}}</ref> At the ceremony, Fakhr-Arai fired five shots at him at a range of ten feet. Only one of the shots hit the Shah, grazing his cheek. Fakhr-Arai was instantly shot by nearby officers. After an investigation, it was determined that Fakhr-Arai was a member of the ],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://persepolis.free.fr/iran/personalities/shah.html|title=The Shah|publisher= Persepolis|accessdate=18 June 2011}}</ref> which was subsequently banned.<ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.iranchamber.com/history/mohammad_rezashah/mohammad_rezashah.php|title=Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi|publisher=Iran Chamber|accessdate=18 June 2011}}</ref> However, there is evidence that the would-be assassin was not a Tudeh member but a religious fundamentalist member of ].<ref>], '']'', John Wiley & Sons, 2003, ISBN 0-471-26517-9</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Dreyfuss|first=Robert|title=Devil's Game: How the United States Helped Unleash Fundamentalist Islam|publisher=Owl Books|year= 2006|isbn=0-8050-8137-2}}</ref> The Tudeh was nonetheless blamed and persecuted.{{Citation needed|date=March 2011}} | |||

| The second attempt on Mohammad Reza Shah's life occurred on 10 April 1965.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-3816(197002)32%3A1%3C19%3AMARFAT%3E2.0.CO%3B2-Q|title=The Journal of Politics: Vol. 32, No. 1 (February 1970)| publisher=JSTOR|accessdate=18 June 2011}}</ref> A soldier shot his way through the Marble Palace. The assassin was killed before he reached the Shah's quarters. Two civilian guards died protecting the Shah. | |||

| According to ] – a former ] officer who defected to the ] – Mohammad Reza Shah was also allegedly targeted by the Soviet Union, who tried to use a TV ] to detonate a bomb-laden ]. The TV remote failed to function.<ref>{{cite book|last=Kuzichkin|first=Vladimir|authorlink=Vladimir Kuzichkin|title= Inside the KGB: My Life in Soviet Espionage|publisher=]|year=1990|isbn=0-8041-0989-3}}</ref> A high-ranking Romanian defector ] also supported this claim, asserting that he had been the target of various assassination attempts by Soviet agents for many years. | |||

| ==Later years== | ==Later years== | ||

| Line 175: | Line 79: | ||

| ==Exile and death== | ==Exile and death== | ||

| ], ] in 1979]] | ], ] in 1979]] | ||

| During his second exile, the Shah traveled from country to country seeking what he hoped would be temporary residence. First he flew to ], ], where he received a warm and gracious welcome from President ]. He later lived in ] as a guest of King ], as well as in the ], and in ] in Mexico near ], as a guest of ]. He suffered from ] that would require prompt surgery. He was offered treatment in ], but insisted on treatment in the ]. | During his second exile, the Shah traveled from country to country seeking what he hoped would be temporary residence. First he flew to ], ], where he received a warm and gracious welcome from President ]. He later lived in ] as a guest of King ], as well as in the ], and in ] in Mexico near ], as a guest of [[José Lóp | ||

| On 22 October 1979, President ] reluctantly allowed the Shah into the United States to undergo surgical treatment at the ]. While in Cornell Medical Center, Shah used the name "]" as his temporary code name, without Newsom's knowledge. | |||

| The Shah was taken later by ] jet to ] in ] and from there to ] at ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1129&dat=19791203&id=3wMOAAAAIBAJ&sjid=-W0DAAAAIBAJ&pg=5084,147980|title=Iran protests Shah's Move to Texas|publisher= Pittsburgh Post-Gazette - News.google.com|date=3 December 1979|accessdate=18 June 2011}}</ref> It was anticipated that his stay in the U.S. would be short; however, surgical complications ensued, which required six weeks of confinement in the hospital before he recovered. His prolonged stay in the U.S. was extremely unpopular with the revolutionary movement in Iran, which still resented the United States' overthrow of Prime Minister Mosaddeq and the years of support for the Shah's rule. The Iranian government demanded his return to Iran, but he stayed in the hospital.<ref>Darling, Dallas. {{dead link|date=June 2011}}. AlJazeera Magazine. 14 February 2009</ref> | |||

| ]200px|Tomb of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, located at the Rifa'i Mosque in Cairo]] | |||

| There are claims that this resulted in the storming of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and the kidnapping of American diplomats, military personnel, and intelligence officers, which soon became known as the ].{{Citation needed|date=December 2012}} According to the Shah's book, '']'', in the end the USA never provided the Shah any kind of health care and asked him to leave the country.<ref>Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. ''Answer to History''. Stein & Day Pub, 1980. ISBN 978-0-7720-1296-8</ref> | |||

| He left the United States on 15 December 1979 and lived for a short time in the ] in ]. The ] in Iran still demanded his and ] immediate extradition to Tehran. A short time after the Shah's arrival, an Iranian ambassador was dispatched to the Central American nation carrying a 450-page extradition request. That official appeal greatly alarmed both the Shah and his advisors. Whether the Panamanian government would have complied is a matter of speculation among historians. | |||

| After that event, the Shah again sought the support of Egyptian president Anwar El-Sadat, who renewed his offer of permanent asylum in Egypt to the ailing monarch. The Shah returned to Egypt in March 1980, where he received urgent medical treatment, including a splenectomy performed by Dr. ],<ref>{{cite web|last=Demaret|first=Kent |url=http://www.people.com/people/archive/article/0,,20076289,00.html|title=Dr. Michael Debakey Describes the Shah's Surgery and Predicts a Long Life for Him|publisher=People|date=21 April 1980|accessdate=31 October 2012}}</ref> but nevertheless died from complications of ] (a type of ]) on 27 July 1980, aged 60. Egyptian President Sadat gave the Shah a state funeral.<ref>. TIME. 31 March 1980</ref> | |||

| Mohammad Reza Pahlavi is buried in the ] in Cairo, a mosque of great symbolic importance. The last royal rulers of two monarchies are buried there, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi of Iran and King ], his former brother-in-law. The tombs lie to the left of the entrance. Years earlier, his father and predecessor, ] had also initially been buried at the Al Rifa'i Mosque. | |||

| ==Legacy== | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1969, the Shah sent one of 73 ] to ] for the historic first lunar landing.<ref>Rahman, Tahir (2007). We Came in Peace for all Mankind- the Untold Story of the Apollo 11 Silicon Disc. Leathers Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58597-441-2</ref> The message still rests on the lunar surface today. He stated in part, "... we pray the Almighty God to guide mankind towards ever increasing success in the establishment of culture, knowledge and human civilization." The Apollo 11 crew visited the Shah during a world tour.<!-- Image with unknown copyright status removed: ] --> | |||

| Shortly after his overthrow, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi wrote an autobiographical memoir ''Réponse à l'histoire'' ('']''). It was translated from the original French into English, ] (''Pasokh be Tarikh''), and other languages. However, by the time of its publication, the Shah had already died. The book is his personal account of his reign and accomplishments, as well as his perspective on issues related to the ] and Western foreign policy toward Iran. The Shah places some of the blame for the wrongdoings of SAVAK and the failures of various democratic and social reforms (particularly through the ]) upon ] and his administration. | |||

| Recently, the Shah's reputation has staged something of a revival, with some Iranians looking back on his era as a time when Iran was more prosperous<ref>Molavi, Afshin, ''The Soul of Iran'', Norton (2005), p. 74</ref><ref> 2 February 2004</ref> and the government less oppressive.<ref>Sciolino, Elaine, ''Persian Mirrors,'' Touchstone, (2000), p.239, 244</ref> Journalist ] reports even members of the uneducated poor – traditionally core supporters of the revolution that overthrew the Shah – making remarks such as 'God bless the Shah's soul, the economy was better then;' and finds that "books about the former Shah (even censored ones) sell briskly," while "books of the Rightly Guided Path sit idle."<ref>Molavi, Afshin, ''The Soul of Iran'', Norton (2005), p.74, 10</ref> | |||

| ===The Shah's writings=== | |||

| Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi published several books in the course of his kingship and two later works after his downfall. | |||

| Among others, these are: | |||

| * Mission for my Country. 1960. | |||

| * The White Revolution. 1967. | |||

| * Toward the Great Civilization. Persian version: Imperial 2536 (1977). English version: 1994. | |||

| * ]. 1980. | |||

| * The Shah's Story. 1980. | |||

| ===Women's rights=== | |||

| {{Main|White Revolution}} | |||

| Under Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's father, the government supported advancements by women against ], ], exclusion from public society, and education ]. However, independent feminist political groups were shut down and forcibly integrated into one state-created institution, which maintained many ] views. Despite substantial opposition from Shiite religious jurists, the Iranian feminist movement, led by activists such as Fatemah Sayyeh, achieved further advancement under Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. His regime's changes focused on the civil sphere, and private-oriented family law remained restrictive, although the 1967 and 1975 '''Family Protection Laws''' attempted to reform this trend.<ref>{{cite book|publisher=Syracuse University Press|title=Gendering the Middle East: Emerging Perspectives|last=Deniz|first=Kandiyoti|year=1996|pages=54–56|ISBN=0-8156-0339-8}}</ref> Specifically, women gained the right to become ministers such as ] and judges such as ], as well as any other profession regardless of their gender. | |||

| ==Marriages and children== | |||

| ], ] and ]]] | |||

| Mohammad Reza Pahlavi married three times: | |||

| ===Fawzia=== | |||

| ] suggested to Reza Shah during the latter's visit to ] that a marriage between the Iranian and Egyptian courts would be beneficial for the two countries and their dynasties.<ref name="Afkhami2008">{{cite book|author=Gholam Reza Afkhami|title=The Life and Times of the Shah|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=pTVSPmyvtkAC&pg=PP2|accessdate=4 November 2012|date=27 October 2008|publisher=University of California Press|isbn=978-0-520-25328-5|pages=35}}</ref> In line with this suggestion, Muhammad Reza Pahlavi and Princess Fawzia married. Dilawar Princess ] (born 5 November 1921), a daughter of King ] and ]; she also was a sister of ]. They married on 15 March 1939 in ] in ].<ref name=Afkhami2008/> Reza Shah did not participate in the ceremony.<ref name=Afkhami2008/> They were divorced in 1945 (Egyptian divorce) and in 1948 (Iranian divorce). Together they had one child, a daughter: | |||

| * HIH Princess ] (born 27 October 1940). | |||

| ===Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiari=== | |||

| His second wife was ] (22 June 1932 – 26 October 2001), a half German half Iranian woman and the only daughter of Khalil Esfandiary, Iranian Ambassador to ], and his wife, the former ]. They married on 12 February 1951,<ref name=Afkhami2008/> when Soraya was 18 according the official announcement, however it rumored that she was actually 16 at the time, the Shah being 36.<ref>Abbas Milani, The Shah (2011), page 156</ref> As a child she was tutored and brought up by Frau Mantel, and hence lacked proper knowledge of Iran as she herself admits in her personal memoirs stating "I was a dunce - I knew next to nothing of the geography, the legends of my country, nothing of its history, nothing of Muslim religion".<ref>Abbas Milani, The Shah (2011), page 155</ref> The Shah and Soraya's controversial marriage ended in 1958 when it became apparent that even through help from medical doctors she could not bear children. Soraya later told ''The New York Times'' that the Shah had no choice but to divorce her, and that he was heavy hearted about the decision.<ref>{{cite news|title=Soraya Arrives for U.S. Holiday|url=http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F20C13FD355D1A7B93C1AB178FD85F4C8585F9|format=PDF|publisher=The New York Times|page=35|date=23 April 1958|accessdate=23 March 2007}}</ref> | |||

| However even after the marriage it is reported that the Shah still had great love for Soraya and it is reported that they met several times after their divorce and that she lived her post-divorce life comfortably as a wealthy lady even though she never remarried;<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2001/10/26/world/princess-soraya-69-shah-s-wife-whom-he-shed-for-lack-of-heir.html |title=Princess Soraya, 69, Shah's Wife Whom He Shed for Lack of Heir |publisher=NY Times |date=26 October 2001 |accessdate=31 October 2012}}</ref> being paid a monthly salary of about 7000 dollars monthly from Iran.<ref>Abbas Milani, The Shah (2011), page 215</ref> Following her death in 2001 at the age of 69 in Paris, an auction of the possessions included a 3 million dollar Paris estate, a 22.37 carat diamond ring and a 1958 Rolls-Royce.<ref>Abbas Milani, The Shah (2011), page 214</ref> | |||

| He subsequently indicated his interest in marrying ], a daughter of the deposed Italian king, ]. ] reportedly vetoed the suggestion. In an editorial about the rumors surrounding the marriage of "a Muslim sovereign and a Catholic princess", the Vatican newspaper, '']'', considered the match "a grave danger,"<ref>Paul Hofmann, ''Pope Bans Marriage of Princess to Shah'', The New York Times, 24 February 1959, p. 1.</ref> especially considering that under the 1917 Code of ] a Roman Catholic who married a divorced person would be automatically, and could be formally, ]. | |||

| ===Farah Diba=== | |||

| Mohammad Reza Pahlavi married his third and final wife, ] (born 14 October 1938), the only child of ], Captain in the Imperial Iranian Army (son of an Iranian ] to the ] Court in ], ]), and his wife, the former ]. They were married in 1959, and Queen Farah was crowned ], or Empress, a title created especially for her in 1967. Previous royal consorts had been known as "Malakeh" (Arabic: ]), or Queen. The couple remained together for twenty years, until the Shah's death. ] bore him four children: | |||

| * HIH Crown Prince ] (born 31 October 1960), heir to the now defunct Iranian throne | |||

| * HIH Princess ] (born 12 March 1963) | |||

| * HIH Prince ] (28 April 1966 – 4 January 2011) | |||

| * HIH Princess ] (27 March 1970 – 10 June 2001) | |||

| ==Wealth== | |||

| Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi inherited the wealth built by his father ] who preceded him as king of Iran and became known as the richest person in Iran during his reign, with his wealth estimated to be higher than 600 million rials <ref>Abbas Milani, The Shah (2011), page 97</ref> and including vast amounts of land and numerous large estates specially in the province of ]<ref>Abbas Milani, The Shah (2011), page 24</ref> obtained usually at a fraction of its real price.<ref>Abbas Milani, The Shah (2011), page 95</ref> Reza Pahlavi facing criticism for his wealth decided to pass on all of his land and wealth to his eldest son Mohammad Reza in exchange for a sugar cube, known in ] as ''habbe kardan''.<ref>Abbas Milani, The Shah (2011), page 96</ref> However shortly after obtaining the wealth Mohammad Reza was ordered by his father and then king to transfer a million tooman or 500,000 dollars to each of his siblings.<ref>Fardust, Memoirs Vol 1, page 109</ref> By 1958 it was estimated that the value of all the companies possessed by the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi has a value of 157 million dollars (1958 USD) with an estimated additional 100 million saved outside Iran.<ref>Abbas Milani, The Shah (2011), page 240</ref> The rumors and constant talk of his, and his family's corruption greatly damaged his reputation and lead to the creation of the ] in the same year and the return of some 2,000 villages inherited by his father back to the people often at very low and discount prices,<ref>Abbas Milani, The Shah (2011), page 241</ref> however it can be argued that this was too little too late as the royal family's wealth and corruption can be seen as one of the factors behind the ] in 1979. The Shah's wealth was even considerable during his time in exile. While staying in the ] he offered to purchase the island that he was staying on for 425 million dollars<ref>Abbas Milani, The Shah (2011), page 428</ref> (1979 USD), however his offer was rejected by the ] claiming that the island was worth far more. On 17 October 1979 again in exile and perhaps knowing the gravity of his illness he split up his wealth between his family members, giving 20% to Farah, 20% to his eldest son Reza, 15% to Farahnaz, 15% to Leila, 20% to his younger son, in addition to giving 8% to Shahnaz and 2% to his granddaughter Mahnaz Zahedi. | |||

| Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was also known for his interest in cars and had a personal collection of 140 classic and sports cars including but not limited to a ] coupe, one of the only six ever made.<ref>{{cite web|last=Farsian |first=Behzad |url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/iran/1473603/Shahs-car-collection-is-still-waiting-for-the-green-light.html |title=Shah's car collection is still waiting for the green light |publisher=Telegraph |date=7 October 2004 |accessdate=31 October 2012}}</ref> | |||

| ==Honors== | |||

| ], Princess ], His Imperial Majesty Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Empress ] and Princess ]. In the middle Princess ] and Crown Prince ].]] | |||

| ] abouth the Shah's 40th birthday, 1959]] | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Iran|1964}} Grand Cordon of the ] of ] (1926) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Iran|1964}} Grand Collar of the ] of ] (1932) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Egypt|1922}} Collar of the Order of Muhammad Ali of ] (1939) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|United Kingdom}} ] (GCB) (1942) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|France}} ] of ] (1945) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Republic of China}} Grand Cordon of the ] of the ], special grade (1946) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|United States|1912}} Chief Commander of the ] of the ] (1947) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Vatican City}} Knight of the ] of the ] (1948) | |||

| * {{Royal Standard-UK}} ] (RVC) (1948) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Iran|1964}} Grand Cordon of the Order of the Zulfiqar of ] (1949) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Jordan}} Collar of the Order of Hussein ibn Ali of ] (1949) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Jordan}} Grand Cordon of the Order of the Renaissance of ] (1949) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Saudi Arabia|1938}} Order of the King Abdul Aziz Decoration of Honour, 1st Class of ] (1955) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|West Germany}} Grand Cordon (Special Class) of the ] of ] (1955) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Lebanon}} Grand Cordon (Special Class) of the Order of Merit of ] (1956) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Spain|1945}} Grand Collar of the Order of the Yoke and Arrows of ] (1957) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Italy}} Grand Cross w/ Collar of the ] of ] (1957) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Libya|1951}} Grand Cordon of the Order of Idris I of ] (1958) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Japan}} Collar of the Supreme ] of ] (1958) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Denmark}} Knight of the ] of ] (1959) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Netherlands}} Grand Cross of the ] (1959) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Pakistan}} Order of Pakistan, 1st Class (1959) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Austria}} Grand Star of the ] (1960)<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.parlament.gv.at/PAKT/VHG/XXIV/AB/AB_10542/imfname_251156.pdf | title = Reply to a parliamentary question | language = German | page=97 | trans_title = | format = PDF | accessdate = 5 October 2012 }}</ref> | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Nepal}} Order of Ojaswi Rajanya of ] (1960) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Greece|royal}} Grand Cross of the ] of ] (1960) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Belgium}} Grand Cordon of the ] of ] (1960) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Norway}} Grand Cross w/Collar of the ] of ] (1961) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Ethiopia|1897}} Grand Collar and Chain of the ] of ] (1964) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Afghanistan|1930}} Grand Cordon of the ] of ] (1965) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|United Arab Republic}} Grand Cordon of the ] of ] (1965) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Argentina}} Grand Cordon of the ] of ] (1965) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Tunisia}} Grand Cordon w/Collar of the Order of Independence of ] (1965) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Brazil}} Grand Collar of the ] of ] (1965) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Morocco}} Grand Cordon of the Order of Muhammad of ] (1966) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Bahrain}} Order of al-Khalifa of ] (1966) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Qatar}} Order of Independence of ] (1966) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Saudi Arabia|1938}} Order of the Badr Chain of ] (1966) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Sudan|1956}} Order of the Chain of Honour of the ] (1966) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Hungary}} Order of the Flag with Diamonds ] (1966) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Yugoslavia}} Grand Cordon of the ] (1966) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Sweden}} Collar of the ] of ] (1967) (Knight–1960) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Malaysia}} ] (DMN) (1968) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Thailand}} Knight of the ] of ] (1968) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Finland}} Commander Grand Cross of the ] (1970) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Oman}} Military Order of ], 1st Class (1973) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Spain|1945}} Grand Collar of the ] of ] (1975) | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Mexico}} Collar of the ] of ] (1975)<ref>, The Royal Ark</ref> | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Czechoslovakia}} Grand Cross of the ], 1st Class w/ Collar of ] (1977) | |||

| == Gallery == | |||

| <center> | |||

| <gallery widths="170px" heights="180px" perrow="4"> | |||

| File:State Flag of Iran (1964).svg|] during the ] 1925 to 1979 | |||

| File:Imperial_Coat_of_Arms_of_Iran.svg|The Coat of Arms of Iran, during ] 1925 to 1979. The ] '''(Atra)''' is seen. (In the circle, right, top). | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| </center> | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| {{Portal|Iran|Biography|Politics}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *], showcases the cars of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{Reflist|30em}} | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| * Yves Bomati, Houchang Nahavandi, ''Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, le dernier shah, 1919-1980'', 620 pages, editions Perrin, Paris,2013, ISBN 2262035873 | |||

| * Abbas Milani. ''The Shah'' (Palgrave Macmillan; 2011) 488 pages; scholarly biography | |||

| *Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, ''Answer to History'', Stein & Day Pub, 1980, ISBN 0-8128-2755-4. | |||

| *Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, ''The Shah's Story'', M. Joseph, 1980, ISBN 0-7181-1944-4 | |||

| *], ''An Enduring Love: My Life with the Shah – A Memoir'', Miramax Books, 2004, ISBN 1-4013-5209-X. | |||

| *], '']'', John Wiley & Sons, 2003, ISBN 0-471-26517-9 | |||

| *], ''The Shah's last ride: The death of an ally'', Touchstone, 1989, ISBN 0-671-68745-X. | |||

| *], ''The Memoirs of Ardeshir Zahedi '', IBEX, 2005, ISBN 1-58814-038-5. | |||

| *Amin Saikal The Rise and Fall of the Shah 1941–1979 Angus and Robertson (]) ISBN 0-207-14412-5 | |||

| *], "The Crisis: the President, the Prophet, and the Shah—1979 and the Coming of Militant Islam" New York: Little, Brown &Co, 2004. ISBN 0-316-32394-2. | |||

| *] (1982). '']''. ]. ISBN 0-679-73801-0 | |||

| *Ali M. Ansari, Modern Iran since 1921 ISBN 0-582-35685-7 | |||

| *Ahmad Ali Massoud Ansari, Me and the Pahlavis, 1992 | |||

| *History of Iran, a short account of the 1953 coup – | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{Commons category|Mohammad Reza Pahlavi}} | |||

| {{Wikiquote}} | |||

| * | |||

| *, "LIBERATION", a Major Motion Picture about the Shah of Iran | |||

| *, Video Archive of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi | |||

| *, Video: I knew Shah | |||

| *, A web site in Persian and English dedicated to Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi | |||

| *, A web site in Persian dedicated to Reza Shah including video clip and photos March 2007 | |||

| *, A web site in Persian dedicated to Ardeshir Zahedi including video clip of marriage with Princess Shahnaz and photos of Shah March 2007 | |||

| *, The Shah's last interview (conducted by David Frost in Panama) | |||

| * – YouTube video | |||

| *, ISNA interview with Dr. Mahmood Kashani {{fa icon}} | |||

| * , Mosaddeq saved the Shah, by Fereydoun Hoveyda | |||

| *, James Risen: Secrets of History: The C.I.A. in Iran – A special report.; How a Plot Convulsed Iran in '53 (and in '79) '']'', 16 April 2000. | |||

| *Stephen Fleischman. , Shah knew what he was talking about: Oil is too valuable to burn, 29 November 2005. | |||

| *Roger Scruton. , In Memory of Iran by Roger Scruton, from 'Untimely tracts' (NY: ], 1987), pp. 190–1 | |||

| *, Brzezinski's role in overthrow of the Shah, ], 10 March 2006. | |||

| *, 'Free elections in 1979, my last audience with the Shah', by Fereydoun Hoveyda, ] | |||

| *, Shah of Iran and US Presidents | |||

| *, Toasts of the President and Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Shah of Iran, at a State Dinner in Tehran: 30 May 1972 | |||

| *, relevant historical pictures | |||

| *, A History Channel video, presented in the context of comments made during a recent debate | |||

| {{S-start}} | |||

| {{S-hou|]|16 October|1919|27 July|1980}} | |||

| {{S-reg|}} | |||

| {{S-bef|before=]}} | |||

| {{S-ttl|title=]|years=16 September 1941 – 11 February 1979}} | |||

| {{S-vac|rows=2|reason=]}} | |||

| {{S-bef|before=''Title created''}} | |||

| {{S-ttl|title=]|years=15 September 1965 – 11 February 1979}} | |||

| {{S-pre|}} | |||

| {{S-bef|before=]}} | |||

| {{S-tul|title=]<br/>]|years=11 February 1979 – 27 July 1980|reason=]}} | |||

| {{S-aft|after=]|as=Shahbanu of Iran}} | |||

| {{S-end}} | |||

| {{Cold War}} | |||

| {{Cold War figures}} | |||

| {{Authority control|VIAF=64009470}} | |||

| <!-- Metadata: see ] --> | |||

| {{Persondata | |||

| |NAME= Pahlavi, Mohammad Rezā | |||

| |ALTERNATIVE NAMES= Pahlavi, Shahanshah Aryamehr Mohammad Rezā | |||

| |SHORT DESCRIPTION=Second Iranian Shah of the Pahlavi dynasty | |||

| |DATE OF BIRTH=26 October 1919 | |||

| |PLACE OF BIRTH=], ] | |||

| |DATE OF DEATH=27 July 1980 | |||

| |PLACE OF DEATH=], ] | |||

| }} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Pahlavi, Mohammad Reza}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Link GA|fa}} | |||

Revision as of 15:35, 5 March 2013

|date=March 2011}}

A general amnesty was issued two days after Mohammad Reza Shah's accession to the throne on 19 September 1941. All political personalities who had suffered disgrace during his father's reign were rehabilitated, and the forced unveiling policy inaugurated by his father in 1935 was overturned. Despite the young Shah's enlightened decisions, the British Minister in Tehran reported to London that "the young Shah received a fairly spontaneous welcome on his first public experience, possibly rather to relief at the disappearance of his father than to public affection for himself."

Oil nationalization and the 1953 coup

Despite the high-level cois claim, asserting that he had been the target of various assassination attempts by Soviet agents for many years.

Later years

Foreign relations

The Shah supported the Yemeni royalists against republican forces in the Yemen Civil War (1962–70) and assisted the sultan of Oman in putting down a rebellion in Dhofar (1971). Concerning the fate of Bahrain (which Britain had controlled since the 19th century, but which Iran claimed as its own territory) and three small Persian Gulf islands, the Shah negotiated an agreement with the British, which, by means of a public consensus, ultimately led to the independence of Bahrain (against the wishes of Iranian nationalists). In return, Iran took full control of Greater and Lesser Tunbs and Abu Musa in the Strait of Hormuz, three strategically sensitive islands which were claimed by the United Arab Emirates.

During this period, the Shah maintained cordial relations with the Persian Gulf states and established close diplomatic ties with Saudi Arabia. Relations with Iraq, however, were often difficult due to political instability in the latter country. The Shah was distrustful of both the Socialist government of Abd al-Karim Qasim and the Arab nationalist Baath party. In April 1969, the Shah abrogated the 1937 Iranian-Iraqi treaty over control of the Shatt al-Arab, and as such, Iran ceased paying tolls to Iraq when its ships used the Shatt al-Arab. The Shah justified his move by arguing that almost all river borders all over the world ran along the thalweg (deep channel mark), and by claiming that because most of the ships that used the Shatt al-Arab were Iranian, the 1937 treaty was unfair to Iran. Iraq threatened war over the Iranian move, but when on 24 April 1969 an Iranian tanker escorted by Iranian warships sailed down the Shatt al-Arab, Iraq being the militarily weaker state did nothing. The Iranian abrogation of the 1937 treaty marked the beginning of a period of acute Iraqi-Iranian tension that was to last until the Algiers Accords of 1975. He financed Kurdish separatist rebels, and to cover his tracks, armed them with Soviet weapons which Israel had seized from Soviet-backed Arab regimes, and then handed over to Iran at the Shah's behest. The initial operation was a disaster, but the Shah continued attempts to support the rebels and weaken Iraq. Then in 1975, the countries signed the Algiers Accord, which granted Iraq equal navigation rights in the Shatt al-Arab river, while the Shah agreed to end his support for Iraqi Kurdish rebels.

The Shah also maintained close relations with King Hussein of Jordan, Anwar Sadat of Egypt, and King Hassan II of Morocco.

On July 1964, Shah Pahlavi, Turkish President Cemal Gürsel and Pakistani President Ayub Khan announced in Istanbul the establishment of the Regional Cooperation for Development (RCD) organization to promote joint transportation and economic projects. It also envisioned Afghanistan's joining some time in the future.

The Shah maintained close relations with Pakistan also. During the Second Indian-Pakistani war of 1965 between Pakistan and India, Iran under the Shah, provided free fuel to the Pakistani planes, which landed on Iranian soil, refueled and then took flight.

The Shah of Iran was the first regional leader to recognize the State of Israel as a de facto state, although when interviewed on CBS 60 Minutes by reporter Mike Wallace, he criticized American Jews for their presumed control over US media and finance.

Modernization and Evolution of Government

Further information: White RevolutionWith Iran's great oil wealth, Mohammad Reza Shah became the pre-eminent leader of the Middle East, and self-styled "Guardian" of the Persian Gulf. In 1961, he defended his style of rule, saying "when Iranians learn to behave like Swedes, I will behave like the King of Sweden."

During the last years of his government, the Shah's government became more centralized. In the words of a US Embassy dispatch, "The Shah's picture is everywhere. The beginning of all film showings in public theaters presents the Shah in various regal poses accompanied by the strains of the National anthem ... The monarch also actively extends his influence to all phases of social affairs ... there is hardly any activity or vocation which the Shah or members of his family or his closest friends do not have a direct or at least a symbolic involvement. In the past, he had claimed to take a two party-system seriously and declared "If I were a dictator rather than a constitutional monarch, then I might be tempted to sponsor a single dominant party such as Hitler organized".

By 1975, he abolished the multi-party system of government in favor of a one-party state under the Rastakhiz (Resurrection) Party. The Shah's own words on its justification was; "We must straighten out Iranians' ranks. To do so, we divide them into two categories: those who believe in Monarchy, the constitution and the Six Bahman Revolution and those who don't ... A person who does not enter the new political party and does not believe in the three cardinal principles will have only two choices. He is either an individual who belongs to an illegal organization, or is related to the outlawed Tudeh Party, or in other words a traitor. Such an individual belongs to an Iranian prison, or if he desires he can leave the country tomorrow, without even paying exit fees; he can go anywhere he likes, because he is not Iranian, he has no nation, and his activities are illegal and punishable according to the law." In addition, the Shah had decreed that all Iranian citizens and the few remaining political parties become part of Rastakhiz.

Achievements

The Shah made major changes to curb the power of certain ancient elite factions by expropriating large and medium-sized estates for the benefit of more than four million small farmers. In the White Revolution, he took a number of major modernization measures, including extending suffrage to women, in accordance to the Islamic Law, the participation of workers in factories through shares and other measures, the improvement of the educational system through new elementary schools and literacy courses set up in remote villages by the Imperial Iranian Armed Forces. The latter step was called "Sepāh e Dānesh", "Army of Knowledge". As a part of the White Revolution, the Armed Forces were engaged in infrastructural and other educational projects throughout the country ("Sepāh e Tarvij va Âbādāni") as well as in health education and promotion ("Sepāh e Behdāsht"). Moreover, he instituted exams for Islamic theologians to become established clerics. As a further step, in the seventies the governmental program of a free of charge nourishment for children at school ("Taghzieh e Rāigān") was implemented. Under the Shah's reign, the national Iranian income showed an unprecedented rise. In the field of diplomacy, Iran realized and maintained friendly relations with Western and East European countries as well as the state of Israel and China and became, especially through the close friendship with the United States, more and more a hegemonial power in the Persian Gulf region and the Middle East. The suppression of the communist guerilla movement in the region of Dhofar in Oman with the help of the Iranian army after a formal request by Sultan Qaboos was widely regarded in this context. As to infrastructural and technological progress, the Shah continued and developed further the policies introduced by his father. As part of his programs, projects in several technologies, such as steel, telecommunications, petrochemical facilities, power plants, dams and the automobile industry may be named. In terms of cultural activities, international cooperations were encouraged and organized, such as the Shiraz Arts Festival. Many Iranian students were sent to and supported in foreign, especially Western countries and the Indian subcontinent. The Aryamehr University of Technology was established as a major new academic institution.

As part of his various financial support programs in the fields of culture and arts, the Shah, along with King Hussein of Jordan donated an amount to the Chinese Muslim Association for the construction of the Taipei Grand Mosque.

Criticism of reign and causes of his overthrow

Main article: Causes of the Iranian Revolution § Policies and policy mistakes of the ShahAt the Federation of American Scientists, John Pike writes:

In 1978 the deepening opposition to the Shah erupted in widespread demonstrations and rioting. Recognizing that even this level of violence had failed to crush the rebellion, the Shah abdicated the Peacock Throne and departed Iran on 16 January 1979. Despite decades of pervasive surveillance by SAVAK, working closely with CIA, the extent of public opposition to the Shah, and his sudden departure, came as a considerable surprise to the US intelligence community and national leadership. As late as 28 September 1978 the US Defense Intelligence Agency reported that the Shah "is expected to remain actively in power over the next ten years."

Explanations for why the Shah was overthrown include that he was a dictator put in place by a non-Muslim Western power, the United States, whose foreign culture was seen as influencing that of Iran. Additional contributing factors included reports of oppression, brutality, corruption, and extravagance. Basic functional failures of the regime have also been blamed — economic bottlenecks, shortages and inflation; the regime's over-ambitious economic program; the failure of its security forces to deal with protest and demonstration; the overly centralized royal power structure.

International policies pursued by the Shah of Iran in order to increase national income by remarkable increases of the price of oil through his leading role in the Organization of Oil Producing Countries OPEC have been stressed as a major cause for a shift of Western interests and priorities and for an actual reduction of their support for him reflected in a critical position of Western politicians and media, especially of the adiministration of US President Jimmy Carter, regarding the question of human rights in Iran, and in strengthened economic ties between the United States of America and Saudi Arabia in the 1970s.

In October 1971, the Shah celebrated the twenty-five-hundredth anniversary of the Iranian monarchy. The New York Times reported that $100 million was spent. Next to the ancient ruins of Persepolis, the Shah gave orders to build a tent city covering 160 acres (0.65 km), studded with three huge royal tents and fifty-nine lesser ones arranged in a star-shaped design. French chefs from Maxim's of Paris prepared breast of peacock for royalty and dignitaries around the world, the buildings were decorated by Maison Jansen (the same firm that helped Jacqueline Kennedy redecorate the White House), the guests ate off Limoges porcelain china and drank from Baccarat crystal glasses. This became a major scandal as the contrast between the dazzling elegance of celebration and the misery of the nearby villages was so dramatic that no one could ignore it. Months before the festivities, university students struck in protest. Indeed, the cost was so sufficiently impressive that the Shah forbade his associates to discuss the actual figures.

However the Shah and the supporters of the Shah argue that the celebrations opened new investments in Iran, improved relationships with the other leaders and nations of the world, and provided greater recognition of Iran. Other actions that are thought to have contributed to his downfall include antagonizing formerly apolitical Iranians — especially merchants of the bazaars — with the creation in 1975 of a single party political monopoly (the Rastakhiz Party), with compulsory membership and dues, and general aggressive interference in the political, economic, and religious concerns of people's lives; and the 1976 change from an Islamic calendar to an Imperial calendar, marking the conquest of Babylon by Cyrus as the first day, instead of the migration of the Prophet Muhammad from Mecca to Medina. This supposed date was designed that the year 2500 would fall on 1941, the year when his own reign started. Overnight, the year changed from 1355 to 2535. During the extravagant festivities to celebrate the 2500th anniversary, the Shah was quoted as saying at Cyrus's tomb: "Sleep easily, Cyrus, for we are awake."

It has been argued that the White Revolution was "shoddily planned and haphazardly carried out", upsetting the wealthy while not going far enough to provide for the poor or offer greater political freedom.

Some achievements of the Shah — such as broadened education — had unintended consequences. While school attendance rose (by 1966 the school attendance of urban seven- to fourteen-year-olds was estimated at 75.8%), Iran's labor market could not absorb a high number of educated youth. In 1966, high school graduates had "a higher rate of unemployment than did the illiterate," and educated unemployed often supported the revolution.

Revolution

Main article: Iranian Revolution

The overthrow of the Shah came as a surprise to almost all observers. The first militant anti-Shah demonstrations of a few hundred started in October 1977, after the death of Khomeini's son Mostafa. A year later strikes were paralyzing the country, and in early December a "total of 6 to 9 million" — more than 10% of the country — marched against the Shah throughout Iran.

On 16 January 1979, he made a contract with Farboud and left Iran at the behest of Prime Minister Shapour Bakhtiar (a long time opposition leader himself), who sought to calm the situation. Spontaneous attacks by members of the public on statues of the Pahlavis followed, and "within hours, almost every sign of the Pahlavi dynasty" was destroyed. Bakhtiar dissolved SAVAK, freed all political prisoners, and allowed the Ayatollah Khomeini to return to Iran after years in exile. He asked Khomeini to create a Vatican-like state in Qom, promised free elections, and called upon the opposition to help preserve the constitution, proposing a "national unity" government including Khomeini's followers. Khomeini rejected Bakhtiar's demands and appointed his own interim government, with Mehdi Bazargan as prime minister, stating that "I will appoint a state. I will act against this government. With the nation's support, I will appoint a state." In February, pro-Khomeini revolutionary guerrilla and rebel soldiers gained the upper hand in street fighting, and the military announced its neutrality. On the evening of 11 February, the dissolution of the monarchy was complete.

Exile and death

During his second exile, the Shah traveled from country to country seeking what he hoped would be temporary residence. First he flew to Assuan, Egypt, where he received a warm and gracious welcome from President Anwar El-Sadat. He later lived in Morocco as a guest of King Hassan II, as well as in the Bahamas, and in Cuernavaca in Mexico near Mexico City, as a guest of [[José Lóp

- http://www.wingnet.org/rtw/RTW005JJ.HTM

- Karsh, Efraim The Iran-Iraq War 1980–1988, London: Osprey, 2002 pp. 7–8

- Bulloch, John and Morris, Harvey The Gulf War, London: Methuen, 1989 page 37.

- ^ Karsh, Efraim The Iran-Iraq War 1980–1988, London: Osprey, 2002 page 8

- "Iran – State and Society, 1964–74". Country-data.com. 21 January 1965. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- Interview with Farah Pahlavi by Mary Bitterman, 15 March 2004.

- Shah of Iran & Mike Wallace on the Jewish Lobby

- America's Mission: The United States and the Worldwide Struggle for Democracy in the Twentieth Century. Tony Smith. Princeton Princeton University Press: p. 255

- Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Mission for my Country, London, 1961, p. 173

- Fred Halliday, Iran; Dictatorship and Development, Penguin, ISBN 0-14-022010-0

- Opposition to Mohammad Reza Shah's Regime

- Robert Graham, Iran, St. Martins, January 1979

- Gholam Reza Afkhami, The Life and Times of the Shah, University of California Press, January 2009, ISBN 0-520-25328-0, ISBN 978-0-520-25328-5

- Abbas Milani, The Persian Sphinx: Amir Abbas Hoveyda and the Riddle of the Iranian Revolution, Mage Publishers, 1 October 2003; ISBN 0-934211-88-4, ISBN 978-0-934211-88-8

- Peter G. Gowing (July/August 1970). "Islam in Taiwan". SAUDI ARAMCO World. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Ministry of Security SAVAK, researched and written by the respected intelligence analyst John Pike.

- Brumberg, Reinventing Khomeini (2001).

- Shirley, Know Thine Enemy (1997), p. 207.

- ^ Harney, The Priest (1998), pp. 37, 47, 67, 128, 155, 167.

- Iran Between Two Revolutions by Ervand Abrahamian, p.437

- Mackay, Iranians (1998), pp. 236, 260.

- Graham, Iran (1980), pp. 19, 96.

- Graham, Iran (1980) p. 228.

- Arjomand, Turban (1998), pp. 189–90.

- Andrew Scott Cooper. The Oil Kings: How the U.S., Iran, and Saudi Arabia Changed the Balance of Power in the Middle East. Simon & Schuster, 2011. ISBN 1-4391-5517-8.

- The New York Times, 12 October 1971, 39:2

- (R.W Cottam, Nationalism in Iran, p. 329)

- Michael Ledeen & William Lewis, Debacle: The American Failure in Iran, Knopf, p. 22

- Abrahamian, Iran Between Two Revolutions (1982) pp. 442–6.

- Books.Google.com, Persian pilgrimages By Afshin Molavi

- http://www.economist.com/news/books-and-arts/21572740-debunking-myths-sustained-ayatollah-khomeinis-republic-waiting-god Iran’s revolution: Waiting for God

- Farmanfarmaian, Mannucher and Roxane. Blood & Oil: Memoirs of a Persian Prince. Random House, New York, 1997, ISBN 0-679-44055-0, p. 366

- Fischer, Michael M.J., Iran, From Religious Dispute to Revolution, Harvard University Press, 1980, p.59

- Amuzegar, The Dynamics of the Iranian Revolution, (1991), pp. 4, 9–12

- Narrative of Awakening : A Look at Imam Khomeini's Ideal, Scientific and Political Biography from Birth to Ascension by Hamid Ansari, Institute for Compilation and Publication of the Works of Imam Khomeini, International Affairs Division, , p. 163

- Kurzman, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, HUP, 2004, p. 164

- Kurzman, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, (2004), p. 122

- "1979: Shah of Iran flees into exile". BBC. 16 January 1979. Retrieved 5 January 2007.

- Taheri, Spirit (1985), p. 240.

- "Imam Khomeini - Return to Tehran". Imam Khomeini. 16 August 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2012.