| Revision as of 02:54, 22 May 2006 editYonnie4th (talk | contribs)1 editm →Go in popular culture← Previous edit | Revision as of 16:11, 22 May 2006 edit undo130.233.22.111 (talk) It is not known as 'wigo' in modern Japanese (or romanization), so giving that spelling without any explanation is misleading and useless.Next edit → | ||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

| '''Go''', also known as '''Wéiqí''' in ] ({{zh-t|圍棋}}; {{zh-s|围棋}}), and '''Baduk''' in ] (]:바둑), is a strategic, ] two-player ] originating in ancient ], before ]. The game is now popular throughout ] and on the Internet. The object of the game is to place stones so they control a larger board territory than one's opponent, while preventing them from being surrounded and captured by the opponent. | '''Go''', also known as '''Wéiqí''' in ] ({{zh-t|圍棋}}; {{zh-s|围棋}}), and '''Baduk''' in ] (]:바둑), is a strategic, ] two-player ] originating in ancient ], before ]. The game is now popular throughout ] and on the Internet. The object of the game is to place stones so they control a larger board territory than one's opponent, while preventing them from being surrounded and captured by the opponent. | ||

| The English name ''Go'' originated from the ] |

The English name ''Go'' originated from the ] pronounciation "go" of the ] 棋/碁; in Japanese the name is written 碁. The ] name Wéiqí roughly translates as "''encirclement chess''", the "''board game of surrounding''", or the "''enclosing game''". Its ancient Chinese name is 弈 ({{zh-p|yì}}). The writings 棋/碁 are variants, as seen in the Chinese ]. The game is also known as 囲碁 (''igo'') in ]. | ||

| == Overview of the game == | == Overview of the game == | ||

Revision as of 16:11, 22 May 2006

| |

| Players | 2 |

|---|---|

| Setup time | No setup needed |

| Playing time | 10 minutes to 3 hours, although tournament games can last more than 16 hours |

| Chance | None |

| Age range | Any |

| Skills | Strategy, Observation |

Go, also known as Wéiqí in Mandarin Chinese (Chinese: 圍棋; Chinese: 围棋), and Baduk in Korean (Hangul:바둑), is a strategic, deterministic two-player board game originating in ancient China, before 200 BC. The game is now popular throughout East Asia and on the Internet. The object of the game is to place stones so they control a larger board territory than one's opponent, while preventing them from being surrounded and captured by the opponent.

The English name Go originated from the Japanese pronounciation "go" of the Chinese characters 棋/碁; in Japanese the name is written 碁. The Chinese name Wéiqí roughly translates as "encirclement chess", the "board game of surrounding", or the "enclosing game". Its ancient Chinese name is 弈 (Chinese: yì). The writings 棋/碁 are variants, as seen in the Chinese Kangxi Dictionary. The game is also known as 囲碁 (igo) in Japanese.

Overview of the game

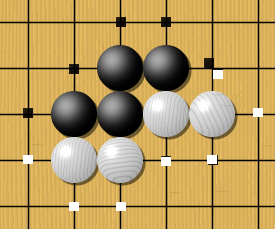

The game of Go is played by alternately placing stones on a grid. The two players, black and white, engage to maximize the territory they control, seeking to surround large areas of the board with their stones, to entrap any opposing stones that invade these areas, and to protect their own stones from capture.

The strategy involved can become very subtle and complex. Some high-level players spend years perfecting strategy. Go is considered by some to be the ultimate strategy game, superior in depth of complexity to Chess, Xiangqi, and Shogi.

Go is typically classified as an abstract board game. However, a resemblance between the game of Go and war is often suggested. The Chinese classic The Art of War, for instance, has sometimes been applied to Go strategy as well. On the other hand, general strategies of Go are well described by proverbs and are applied in other contexts such as management.

Real wars end when the participants sign treaties. Likewise, in Go, the players have to agree that the game has ended. Only then are the score and the winner finally determined.

History

Main article: History of GoThe origins of the game lie in China and the earliest references come from China in the 6th century BC (548 BC, from Zuo Zhuan). Except for changes in the board size and starting position, Go has essentially kept the same rules since that time, which quite likely makes it the oldest board game still played today.

According to legend, the game was used as a teaching tool after the ancient Chinese emperor Yao 堯 (2337 - 2258 BC) designed it for his son, Danzhu, who he thought needed to learn discipline, concentration, and balance. Another suggested genesis for the game states that in ancient times, Chinese warlords and generals would use pieces of stone to map out attacking positions. Further and more plausible theories relate Go equipment to divination or flood control.

Before the industrial age in China, Go was long perceived as the popular game of the elite aristocratic class while Xiangqi (Chinese chess) was perceived as the game of the masses. Go was considered one of the cultivated arts of the Chinese scholar gentleman (junzi), along with Calligraphy, Painting and playing the Guqin, known as 琴棋書畫 (四艺, Pinyin: Sìyì), or the Four Arts of the Chinese Scholar.

Go had reached Japan from China by the 7th century, and gained popularity at the imperial court in the 8th. By the beginning of the 13th century, the game was played in the general public in Japan.

Early in the 17th century, the then best player in Japan, Honinbo Sansa, was made head of a newly founded Go academy (the Honinbo school, the first of several competing schools founded about the same time), which developed the level of playing greatly, and introduced the martial arts style system of ranking players. The government discontinued its support for the Go academies in 1868 as a result of the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate.

In honour of the Honinbo school, whose players consistently dominated the other schools during their history, one of the most prestigious Japanese Go championships is called the "Honinbo" tournament.

Historically, Go has been unequal in terms of gender. However, the opening of new, open tournaments and the rise of strong female players, most notably Rui Naiwei, has in recent years legitimised the strength and competitiveness of emerging female players.

Around 2000, in Japan, the manga (Japanese comic) and anime series Hikaru no Go popularized Go among the youth and started a Go boom in Japan. In January 2004, the Hikaru no Go manga began running in the US (monthly) edition of Shonen Jump. Whether this will lead to a strong following in the US is yet to be seen.

Scott A. Boorman's The Protracted Game: A Wei-Chi Interpretation of Maoist Revolutionary Strategy likens the game to historical events, saying that the Maoists were better at surrounding territory.

Nature of the game

Although rules of Go can be written so that they are very simple, the game strategy is extremely complex. Go is a perfect information, deterministic, strategy game, putting it in the same class as chess, checkers (draughts), and reversi (othello). It greatly exceeds draughts and reversi in depth and complexity, and transcends even the complexity of chess. Its large board and lack of restrictions allows great scope in strategy. Decisions in one part of the board may be influenced by an apparently unrelated situation in a distant part of the board. Plays made early in the game can shape the nature of conflict a hundred moves later.

The game emphasizes the importance of balance on multiple levels, and has internal tensions. To secure an area of the board, it is good to play moves close together; but to cover the largest area one needs to spread out. To ensure one does not fall behind, expansionist play is required; but playing too broadly leaves weaknesses undefended that can be exploited. Playing too low (close to the edge) secures insufficient territory and influence; yet playing too high (far from the edge) allows the opponent to invade. Many people find the game attractive for its reflection of the contradictary demands found in real life. Indeed, a common saying is "life is like Go".

The game complexity of Go is such that even an introduction to strategy can fill a book, and many good introductory books are available. See Go strategy and tactics for a very brief introduction to the main concepts of Go strategy.

It is commonly said that no game has ever been played twice. This may be true: On a 19×19 board, there are about 3×0.012 = 2.1×10 possible positions, most of which are the end result of about (120!) = 4.5×10 different (no-capture) games, for a total of about 9.3×10 games. Allowing captures gives as many as

possible games, all of which last for over 4.1×10 moves! (For two comparisons: the number of legal positions in chess is estimated to be between 10 and 10; and physicists estimate that there are not more than 10 protons in the entire visible universe.)

Traditional equipment

Although one could play Go with a piece of cardboard for a board and a bag of plastic tokens, many Go players pride themselves on their game sets.

The traditional Go board (called a goban in Japanese) is solid wood, from 10–18 cm thick, and often stands on its own attached legs. It is preferably made from the rare golden-tinged Kaya tree (Torreya nucifera), with the very best made from Kaya trees up to 700 years old. More recently, the California Torreya (Torreya californica) has been prized for its light color and pale rings. Other woods often used to make quality table boards include Hiba (Thujopsis dolabrata), Katsura (Cercidiphyllum japonicum), and Kauri (Agathis).

Players sit on reed mats (tatami) on the floor to play. The stones (go-ishi) are kept in matching solid wood pots (go-ke) and are made out of clamshell (white) and slate (black) and are extremely smooth. The classic slate is from the nachiguro slate mined in Wakayama prefecture and the clamshell from the Hamaguri clam. The natural resources of Japan have been unable to keep up with the enormous demand for the native clams and slow-growing Kaya trees; both must be of sufficient age to grow to the desired size, and they are now extremely rare at the age and quality required, raising the price of such equipment tremendously.

In clubs and at tournaments, where large numbers of sets must be maintained (and usually purchased) by one organization, the expensive traditional sets are not usually used. For these situations, table boards (of the same design as floor boards, but only about 2–5 cm thick and without legs) are used, and the stones are made of glass rather than slate and shell. Bowls will often be plastic if wooden bowls are not available. Plastic stones could be used, but are considered inferior to glass as they are generally much lighter, and most players find that not even the lower price justifies their unpleasantness.

Traditionally, the board's grid is 1.5 shaku long by 1.4 shaku wide (455 mm by 424 mm) with space beyond to allow stones to be played on the edges and corners of the grid. This often surprises newcomers: it is not a perfect square, but is longer than it is wide, in the proportion 15:14. Two reasons are frequently given for this. One is that when the players sit at the board, the angle at which they view the board gives a foreshortening of the grid; the board is slightly longer between the players to compensate for this. Another suggested reason is that the Japanese aesthetic finds structures with geometric symmetry to be in bad taste.

Traditional stones are made so that black stones are slightly larger in diameter than white; this is probably to compensate for the optical illusion created by contrasting colours that would make equal-sized white stones appear larger on the board than black stones. The difference is slight, and since its effect is to make the stones appear the same size on the board, it can be surprising to discover they are not.

The bowls for the stones are of a simple shape, like a flattened sphere with a level underside. The lid is loose-fitting and is upturned before play as a tray to collect stones captured during the game. The bowls are usually made of turned wood, although small lidded baskets of woven bamboo or reeds make an attractive cheaper alternative.

The traditional manner to place a Go stone is to hold it between the tips of the outstretched index and middle fingers and then strike the board firmly to create a sharp click. Many consider the acoustic properties of the wood of the board to be quite important. The traditional goban will usually have its underside carved with a pyramid called a heso recessed into the board. Tradition holds that this is to give a better resonance to the stone's click, but the more conventional explanation is to allow the board to expand and contract without splitting the wood. A board is seen as more attractive when it is marked with slight dents from decades (or centuries) of stones striking the surface.

Rules

Main article: Rules of Go

Basic rules

- Two players, black and white, take turns placing a stone (game piece) on the points (intersections) of a 19 by 19 board (grid). Black moves first.

- Stones must have liberties (empty adjacent points) to remain on the board. Stones connected by lines are called chains, and share their liberties.

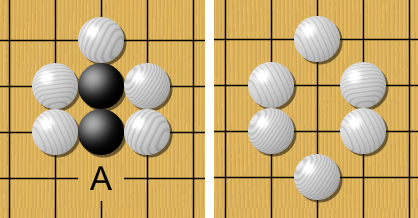

- When a stone or a chain of stones is surrounded by opponent stones, so that it has no more liberties, it is captured and removed from the board.

- If a stone has no liberties as soon as it is played, but simultaneously removes the last liberty from one or more of the opponent's chains, the opponent's chains are captured and the played stone is not.

- "Ko rule": A stone cannot be played on a particular point if doing so would recreate the board position that existed after the same player's previous turn.

- A player may pass instead of placing a stone. When both players pass consecutively, the game ends and is then scored.

A player's score is the number of empty points enclosed only by his stones plus the number of points occupied by his stones. The player with the higher score wins. (Note that there are other rulesets that count the score differently, yet almost always produce the same result.) For a more detailed treatment, see Rules of Go.

This is the essence of the game of Go. The risk of capture means that stones must work together to control territory, which makes the gameplay very complex and interesting. (Also see strategy.)

Go allows one to play not only even games (games between players of roughly equal strength) but also handicap games (games between players of unequal strength); see optional rules.

Optional rules

Optional Go rules may set the following:

- compensation points, almost always for the second player, see komi;

- compensation stones placed on the board before alternate play, allowing players of different strengths to play interesting games (see Go handicap for more information).

Strategy

Main article: Go strategy and tacticsBasic strategic aspects include the following:

- Connection: Keeping one's own stones connected means that fewer groups need defense.

- Cut: Keeping opposing stones disconnected means that the opponent needs to defend more groups.

- Life: This is the ability of stones to permanently avoid capture. The simplest way is for the group to surround two "eyes" (separate empty areas), so that filling one eye will not kill the group and is therefore suicidal.

- Death: The absence of life, resulting in the removal of a group.

- Invasion: Penetration into an opponents claimed territory as a means of swaying the balance of territory.

Philosophy

Go is deep, as playing against any stronger player will demonstrate (depth of the game as established by ELO ranking in Go). With each new level (rank) comes a deeper appreciation for the subtlety involved, and for the insight of stronger players. Beginners often start by randomly placing stones on the board, as if it were a game of chance — and they inevitably lose to experienced players. But soon an understanding of how stones connect to form strength develops, and shortly afterward a few basic common opening sequences may be understood. Learning the ways of life and death helps to develop one's situational judgement.

Further experience yields an understanding of the board, the importance of the edges, then the efficiency of developing (in the corners first, then sides, then centre). Soon, the advanced beginner understands that territory and influence are somewhat interchangeable — but there needs to be a balance. Best is to develop more or less at the same pace as the opponent, in both territory and influence. This intricate struggle of power and control makes the game highly dynamic.

Computers and Go

Main article: Computer GoAlthough much effort has gone in to programming computers to play Go, even the strongest programs are no better than an average club player, and would easily be beaten by a strong player even getting a nine-stone handicap. Strong players have even beaten computer programs at handicaps of twenty-five stones. Of course, strong players do not currently have much interest in computer Go programs as opponents, as they do not yet play well enough. This is attributed to many qualities of the game, including the "optimising" nature of the victory condition, the large number of legal moves, the large board size, the nonlocal nature of the Ko rule, and the high degree of pattern recognition involved. On the other hand, a chess-playing computer, Deep Blue, beat the world champion in 1997. For this reason, many in the field of artificial intelligence consider Go to be a better measure of a computer's capacity for thought than chess.

On the other hand, none of these factors prevents computers from playing far better than human players in certain endgame situations, exactly as in the case of chess. In chess, this is due to the use of end game tablebases; in Go, to an application of the kind of game analysis pioneered by John H. Conway, who invented surreal numbers to analyze games and Go endgames in particular, an idea much further developed in application to Go by Elwyn R. Berlekamp and David Wolfe. It is outlined in their book, Mathematical Go (ISBN 1568810326). While not of general utility in most play, it greatly aids the analysis of certain classes of positions.

Use of computer networks to allow humans to meet, discuss games, and play one another, is becoming very common, with many strong players regularly playing online. See Additional Resources below for more information.

Other board games sometimes compared with Go

This is a list of some games that are played with similar equipment or come from the same area.

- Variations of chess

- Chess (Western): This game dominates Western game culture; its history in the culture stretches back many centuries.

- The Game of the Amazons: A cross between Go and Chess. In this game the pieces have the same movements as the Queen in Chess. After a player moves, the piece fires an arrow (that has the same movement as a Queen in Chess). An arrow blocks the paths of other pieces and arrows. The player who can move last wins. There can never be a draw.

- Janggi: This is the Korean variant of Chess, usually called "Korean Chess". It is also very different from Go in game play. Go and Janggi are the two main board games played in Korea.

- Shogi 将棋: Early Western literature often referred to Go as "Japanese Chess". The Japanese do have their own game called Shogi; it is much more similar to the other Chess variants than to Go. Shogi schools were founded in Japan about the same time as Go schools, and the game held more players throughout history than Go did. But Shogi is considered "lower class" compared with Go. Until recently, professional Go players in Japan often played Shogi as amateur and vice versa, but this habit has decreased because they now have no time to play other games.

- Xiangqi 象棋: This is the Chinese variant of Chess, usually called "Chinese chess" by English speakers. Like most Chess variants, it has great depth of strategy, but bears few similarities to Go in game play. Xiangqi, like Go, is played on points rather than squares.

- Connection games. These are the most similar to Go in terms of style and strategy. One significant difference between Go and many connection games is the number of goals. In Hex, for example, there is only one goal: to connect your two sides. While this leads to significant strategic complexity (especially as the board size increases), in Go there are usually numerous different battles going on simultaneously.

- Hex and TwixT are connection games. Like Go, these have cutting and connecting tactics, but Hex is played on a hexagonal lattice. Mathematician John Nash independently invented a version of this game while at Princeton University, called Nash, in response to Go.

- Y, Havannah, and *Star are connection games similar to Hex, but of more depth.

- Played on a Go board

- Connect6: Played with the same equipment as Go (a 19x19 grid, black and white stones), in these games the goal is to create six stones in a row.

- Gomoku, Renju and Pente: Played with the same equipment as Go (a 19x19 grid, black and white stones), in these games the goal is to create five stones in a row. The game style is thus much shorter and involves less strategy than Go.

- Philosopher's Football: Played with a Go board restricted to 15x19 grid, and black and white stones. The goal is to get the football (the white stone) across the respective goal line.

- Other similar-looking games

- Abalone is a board game with black and white marbles. Strategy is somewhat of a cross between Reversi and Sumo wrestling, the goal being to push the other player's marbles off the playing surface.

- Alak is a Go-like game restricted to a single spatial dimension.

- Reversi: Marketed by Mattel as "Othello", Reversi bears superficial similarity to Go, with black and white circular pieces, an undifferentiated grid for a board, simple rules, and a goal of covering more of the board than the opponent. The game play is quite unlike Go, however, as it is based on flanking the opponent's pieces for capture. Captured pieces change their color.

Go in popular culture

Go has been mentioned in many novels and short stories published in the Orient, and occasionally turns up in Western media as well.

In 1951, Nobel Prize-winning author Yasunari Kawabata published The Master of Go, a short novel based upon an epic game that took place over the course of several months in 1938. An English translation appeared in 1972, around the time of Kawabata's death. Go also features (as "Wéi-chí") as a favourite pastime of and philosophical inspiration for the archvillan Howard Devore in the Chung Kuo novels by David Wingrove.

Go is featured in the cold war thriller, Shibumi by Trevanian. The central character spends his adolescence studying the game under a master, and the major chapters of the book reflect Go strategies.

Shan Sa, a Chinese writer who lives in France, wrote La Joueuse de Go, where a Chinese girl plays Go with a Japanese soldier and wins, although they are both extremely strong players.

Go is featured in Scarlett Thomas's book PopCo. Alice Butler, the main character, works for a giant toy company where games of Go are encouraged to spark creativity.

The world of the fantasy series The Wheel of Time has a similar game, called Stones, with a hexagonal base shape instead of square.

In the science fantasy book The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula Le Guin, Go is played by the two protagonists when they are stuck in an ice tempest.

The book The Way of Go by Troy Anderson likens the game to a rosetta stone for understanding the underpinnings of strategy, especially for business.

In the webcomic Disassemblance, the two main characters are occasionally seen discussing various subjects over a game of Go.

The game of Go plays a part in the American TV miniseries, Wild Palms which references a piece of computer technology called a "Go chip." Go figures prominently in the introduction of La Femme Nikita to the mysterious character of Jurgen during an important character arc in the television series La Femme Nikita. The game also appeared in an episode of Star Trek: Enterprise entitled "The Cogenitor" in which it was revealed that Charles Tucker plays the game. In another Gene Roddenberry show, Andromeda, Dylan Hunt and Gaheris Rhade both play a futuristic version of the game, apparently on three boards at once. During episode 15 of season 3 of the television show 24, several scenes took place in an underground Chinese Go club uncharacteristically populated by beautiful women. The characters even called it a "Go club". A 1980s TV series called Chessgame starred Terence Stamp as a spy master who would spend long periods studying a Go board.

Hikaru no Go is a manga and anime series, in which a boy is taught to play Go by the spirit of an ancient Go player. At the end of each episode in the original anime, there is a short segment of approximately three minutes where a simple concept of Go is taught. Through the first few episodes, a new player can be taught the concepts of the game in a very simple and easy to understand format. This segment appears to be mainly geared towards children. Hikaru No Go was extremely popular during its original run, and was also highly regarded by critics. A direct result of its success was that Go's popularity (which had been in decline for years in Japan) skyrocketed, especially amongst the young, and its popularity also increased in China and Korea. Today interest in the game remains relatively high, in large part thanks to this series.

In the manga and anime series "Naruto", Shikamaru is mentioned to be a master at Shogi and Go. Although seemingly unmotivated and lazy, his intellect is proved when playing his sensei in these games. He never loses. In fact, a habit Shikimaru developed when playing Shogi and Go is even carried into his battles.

One popular Chinese/Japanese movie is Mikan no taikyoku (1982) aka The Go Masters. The movie depicts the time period when the Japanese army invaded China. The story begins when a Japanese Army Captain forces a famous Chinese Go player to play at a Go match. Due to resentment of the invasion, the Chinese player cuts off the finger that is used to hold Go stones. The story ends at a post-war time, where both the Japanese Captain and the Chinese Go player meet and play a peaceful game.

Go was depicted in the films Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison, A Beautiful Mind, Pi, Restless and Hero among many others. See the Internet Go Filmography for an extensive list.

Go is depicted in the movie Pi.

The Go world

Ranks

In countries where Go is popular, ranks are employed to indicate playing strength. From about the sixteenth century, the Japanese formalised the teaching and ranking of Go. The system is comparable to that of martial arts schools; and is considered to be derived ultimately from court ranks in China.

Beginning players today start at a rank of between 25 and 30 kyu 級. The kyu ranking then decreases in magnitude as the player becomes stronger, dropping down to 1 kyu or 1k. Since beginners will commonly progress through elementary concepts quickly, it may be difficult to set a solid kyu ranking for new players. Players who have progressed through the kyu ranks and passed the 1 kyu mark are then ranked at 1 dan 段 or 1d, sometimes called shodan 初段. The player then could advance through the amateur dan ranks up to amateur 7 dan, which only few players achieve. That playing level is roughly equivalent to where the ranks for professionals start with pro 1 dan going up to 9 dan (also sometimes called ping or p as in 9p to avoid confusion between a 1 dan professional and a weaker amateur 6 dan). The distinction between each amateur rank is, by definition, one handicap stone. Professional ranks are awarded by professional organizations and though they are less well defined, they are closer, so that an average 1p might need three handicap stones against a prime 9p (although they would play even games if they were to meet in a tournament).

Among amateur players, handicaps are determined by the difference in ranks. If a 3k and a 7k player were to play each other, the 7k player would place four handicap stones at the start of the game. Handicaps up to nine stones are common in club play, and correspond well to rank differences. In a small club, ranks may be decided informally and adjusted when players consistently win or lose. In a larger club, a mathematical ranking system gives better results. Players can then be promoted or demoted based on their strength as calculated from their wins and losses.

Timing

Like many other games, a game of Go may be timed. There are four typical methods of timing a game:

- Absolute: a specific amount of time is given for the entire game, regardless of how fast or slow each player is. This is extremely rare.

- Byo-Yomi (Japanese Timing): After the main time is depleted, a player has a certain number of time periods (typically around 30 seconds). After each move, the number of time periods that the player took (possibly zero) is subtracted. For example, if a player has three 30-second time periods and takes 30 or more (but less than 60) seconds to make a move, he loses one time period. With 60-89 seconds, he loses two time periods, and so on. If, however, he takes less than 30 seconds, the timer simply resets without subtracting any periods. This is written as <maintime> + <byo-yomi time period>x<number of byo-yomi time periods>.

- Canadian Byo-Yomi: After the main time is depleted a player must make a certain number of moves within a certain period of time. For example, 5 moves within 2 minutes. If 5 moves are made in time, the timer resets to 2 minutes again. This is written as <main time>/<byo-yomi time period>/<number of moves to be completed in each byo-yomi time period>. (The Origins of Canadian Byo-Yomi)

- Progressive Byo-Yomi: usually this is based on Canadian Byo-Yomi, where after main time is depleted the first number of moves must be played in a time, but the next number of moves may be different and played in a different amount of time. For instance, in one amateur tournament the main time of 50 minutes was followed by twenty moves in five minutes, then forty moves in five minutes, then sixty moves in five minutes (the last time period being repeated until the game ended). Thus, this tournament's timing was written 50+20/5+40/5+60/5 (it is common to leave minutes as numbers without units while seconds are usually written in the form 5s).

Japanese Timing is equivalent to Canadian Byo-Yomi when the "certain number of moves" is equal to one.

Top players

Main article: Go playersAlthough the game was invented and developed in China, Japanese players dominated the international Go scene for most of the twentieth century. However, top players from China (since the 1980s) and South Korea (since the 1990s) have reached an even higher level. Nowadays, top players from these three countries are of comparable strength, although top Korean players seem to have an edge, dominating the major international titles, winning 23 tournaments in a row between 2000 and 2002. All three countries have a number of professional Go tournaments. The top Japanese tournaments have a prize purse comparable to that of professional golf tournaments in the United States though tournaments in China and Korea are less lavishly funded.

Players from other countries have traditionally been much weaker, except for some players who have taken up professional courses in one of the Asian countries. This is attributed to the fact that details of the game have been unknown outside of Asia for most of the game's history. A German scientist, Otto Korschelt, is credited with the first systematic description of the game in a Western language in AD 1880; it was not until the 1950s that Western players would take up the game as more than a passing interest. In 1978, Manfred Wimmer became the first Westerner to receive a professional player's certificate from an Asian professional Go association. It was not until 2000 that a Westerner, Michael Redmond, achieved the top rank awarded by an Asian Go association.

See also

- Games played with Go equipment

- Go concepts

- Go handicap

- Go proverb

- Go competitions

- Iemoto

- List of board games

- List of free Go programs

- List of Go topics

- List of Go organizations

- Nihon Ki-in

- Hanguk Kiwon

- Zhongguo Qiyuan

- Kansai Ki-in

- Computer Go

- Computer Go programming

- Game complexity

Books

- Life, Liberty & the Pursuit of Territory, Richard Zhang, Ryan Wang, Compupress, 2006. http://www.lifelibertyterritory.com

- Go for Beginners, Iwamoto Kaoru, Ishi Press, Tokyo, 1972. ISBN 0870401661

- An Introduction to Go, James Davies, Richard Bozulich, Ishi Press, Tokyo, 1984.

- Lessons in the Fundamentals of Go, Kageyama Toshiro, Kiseido Publishing Company, 1978. (A more advanced book, suitable for people with a certain amount of experience.)

- Basic Techniques of Go, Haruyama Isamu, Nagahara Yoshiaki, Ishi Press, Tokyo, 1969. (Again, a more advanced book.)

- Go: the World's Most Fascinating Game, Vol 1 - Introduction, Vol 2 - Basic Techniques, Nihon Kiin, 1973.

- The Protracted Game: A Wei-Chi Interpretation of Maoist Revolutionary Strategy, Scott A. Boorman, Oxford University Press, 1969.

- The Way of Go, Troy Anderson, Free Press, 2004. ISBN 0743258142

External links

Learning Go

- Life, Liberty & the Pursuit of Territory A guide for the beginning player written in English, not translated from other languages

- Let My People Go!

- The Interactive Way To Go is an excellent resource to learn the basics; includes Java applets.

- British Go Association's introduction to Go

- The Rules of Go

- How To Play Go

- How To Play Go

- Samarkand is owned by Janice Kim 3p and has a very good beginner introduction.

- Tel's Go Notes where to look when you understand the rules and wonder what to do next.

- goproblems.com has over 3000 problems for practice in a Java applet.

- GoBase has a collection of 750 problems used in Korea to help develop players of amateur dan strength.

- Teach Yourself Go explains the rules of Go and, through step-by-step illustrations, shows how to play the game. The book also covers the origins of the game and its history and culture.

Resources

- Sensei's Library is a wiki devoted entirely to the game of Go - it even has special markup for displaying Go diagrams.

- The Usenet newsgroup rec.games.go has its own FAQ document, the rec.games.go FAQ.

- Annotated Go Bibliographies Offers reviews of Go books old and new alike.

- Go Base has a particular emphasis on the coverage of the world Go scene, with regularly updated news about all major professional and amateur tournaments. You can register and access a huge database of Go games directly on the site. It also hosts articles, studying material, and much more.

- Go Equipment Information including classifications of boards by grain and classic composition.

- The Go Link Explorer A large collection of information and resources about Go, organised by category.

- London Open gives a flavour of what a Go tournament is like. (Uses Java)

Internet Go

Go can be played on the Internet against opponents from around the world on numerous Go servers:

- The BrainKing, web-based server, Go and many other games, localized to 15 languages.

- The DashN Go Server, Korean server with an English Windows client.

- The Dragon Go Server, a turn-based server run on open source software.

- The Kiseido Go Server is such a server, complete with its own easy-to-use Java client, teaching facilities and introductory material.

- The Kurnik Go, with a Java-based browser client.

- The Legend Go Server, located in Taiwan, with its own English client.

- The LittleGolem, another turn-based server, this one centred around tournament play.

- The Oro Go, located in Korea, with its own client.

- The Pandanet Internet Go Server, the "original" server. Several official and 3rd party clients are available.

- The Playray Go, quite a new browser based Go server, includes many options and a ranking system of its own. Players from various countries.

- The Qingfeng Go Server, located in China, with its own client.

- The Tom Duiyi, located in China, with its own client.

- The Tygem Go, located in Korea, with its own client.

- The Yahoo Game Server, with a Java-based browser client.

- The YourturnMyturn.com, another turnbased site with also other games.

- The Online-Go.com, A new, browser-based, turn-based server with mini-tournaments, conditional moves and many other options.

- The FlyOrDie.com, browser-based, multinational go server.

- The FICGS.com, browser-based, multinational chess & go server.

Recorded games

- The popular SGF file format is used to exchange Go lessons and recorded games.

- Fuseki.Info - Online professional Go games database (more than 35000 games). Contains game records, game lists, fuseki and joseki trees. More than 3000 games for free.

- go4go.net - Approximately 10,000 professional games can be reviewed for free and without registration.

- Several free reading and authoring programs are listed at Gobase's SGF editors list

- gobase.org also hosts a database of more than 30000 professional Go games in SGF format (free registration required, which takes 1-2 days to process)

- My Friday Night Files provides more than 2000 professional games, including almost all known games of Cho Chikun

- A smaller collection of professional games in SGF format is available without registration at Andries E. Brouwer's Go Games.

- Amateur games are reviewed at The Go Teaching Ladder.

Go software

Go engines

- Aya, free and strong Go-playing program, ~10-12 Kyu

- GNU Go, free (in both senses) Go-playing engine, 8-9 Kyu

- Igowin is a free 9x9 version of David Fotland's The Many Faces of Go

- GoTools, free (but a password will be required) Java applet for solving life-and-death problems (Tsumego), of professional level. (Those problems, set in limited spaces, with a clear objective, are essentially the only subdomain of go where real progress have been made in Artificial Intelligence.)

- Moyoman is an open-source Go playing program written in Java.

Go clients

- GoGui, SGF editor and client for GNU Go (you can play standalone) in Java.

- gGo, SGF editor and client for IGS, in Java; and native variants, qGo and glGo (has a 3D display)

- CGoban1, Go client (Linux, etc)

- CGoban2, Go client for KGS in Java. Also functions as an SGF editor.

- Goban, standalone (against GNU Go) and Internet Go client for Mac OS X

- HandyGo, J2ME Go client that runs on java-enabled cellphones and PDAs.

- Orneta Go, Windows Mobile Go client for Smartphone and Pocket PC.

- TanGo, Client for Windows. Written in Visual Basic. Open source. Also contains an SGF viewer, GNU Go player and NNGS Server.

- GO.FEUP, GO.FEUP 3D GO Game (free Windows 3D Opengl Game with HumanVsCPU and CPUvsCPU features, now in French too).

Study aids

- GoGrinder, a Java program for practising Go problems.

- Hikarunix, a Linux live CD which includes GNU Go, Go clients, games and documentation.

- Go Game Assistant, SGF viewer/editor for Windows.

- Uligo, Multiplatform program to study Tsumego, life and death problems.

- Interactive Go Maps, web-based program for visualizing such concepts as Influence, Concentration, Tension and Instability.

- Moyo Go Studio Fuseki, Joseki, Tesuji, "Good Shape"- Pattern Expert, SGF Editor, SQL database and GNU Go Client.

- SmartGo Windows program to play, study, and print Go games. English, Japanese, Korean, and Russian.

Utilities

- Kombilo is a free database and pattern search engine for sgf game records.

- BiGo Assistant is a database of professional and amateur Go games. It allows searching by fuseki, joseki, positions and game information fields.

- WikiTeX Go supports SGF for inserting Go diagrams directly into Wiki articles.

- PilotGOne A Go game recorder and SGF viewer/editor for PalmOS.

- GoSuite A Go game recorder and SGF viewer/editor for PocketPC, also including the Vieka GNU Go port for PocketPC allowing you to play against your PocketPC PDA.

- Games::SGF::Tournament - Perl module useful for creating web pages with tournament tables directly from sets of SGF files, also available through CPAN.

- mgo, J2ME Go game recorder that runs on java-enabled mobiles and PDAs. Development status is alpha but already useful.

- YAMGT, J2ME sgf player, recorder that runs on java-enabled mobiles.

Disambiguation

- Go is also the name of Waddington's travel game Go (Licensed to Gibson in the US).

- Ing Chang-Ki, the late wealthy promoter of Go (particularly in the U.S.) proposed spelling the word in English as "goe" to differentiate it from the verb "to go", but this spelling is not widely used —even in events which are sponsored by the Ing foundation.

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

Categories: