| Revision as of 16:12, 5 July 2013 edit82.1.219.132 (talk) →Notable convicts transported to Australia← Previous edit | Revision as of 07:13, 13 July 2013 edit undoCollingwood26 (talk | contribs)1,072 editsNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

| During the late 18th and 19th centuries, large numbers of ]s were ] to the various ] by the British government. One of the primary reasons for the British settlement of Australia was the establishment of a ] to alleviate pressure on their overburdened ] facilities. Over the 80 years more than 165,000 convicts were transported to Australia.<ref></ref> | During the late 18th and 19th centuries, large numbers of ]s were ] to the various ] by the British government. One of the primary reasons for the British settlement of Australia was the establishment of a ] to alleviate pressure on their overburdened ] facilities. Over the 80 years more than 165,000 convicts were transported to Australia.<ref></ref> | ||

| The number of convicts pales in comparison to the immigrants who arrived in Australia in the ]. In 1852 alone, 370,000 immigrants arrived in Australia. By 1871 the total population had nearly quadrupled from 430,000 to 1.7 million people.<ref>http://www.cultureandrecreation.gov.au/articles/goldrush/</ref> The last convicts to be transported to Australia arrived in ] in 1868. | The number of convicts pales in comparison to the immigrants who arrived in Australia in the ]. In 1852 alone, 370,000 immigrants arrived in Australia. By 1871 the total population had nearly quadrupled from 430,000 to 1.7 million people.<ref>http://www.cultureandrecreation.gov.au/articles/goldrush/</ref> The last convicts to be transported to Australia arrived in ] in 1868. The convict transportation system has also been referred to as white slavery. | ||

| ==Reasons for transportation== | ==Reasons for transportation== | ||

Revision as of 07:13, 13 July 2013

During the late 18th and 19th centuries, large numbers of convicts were transported to the various Australian penal colonies by the British government. One of the primary reasons for the British settlement of Australia was the establishment of a penal colony to alleviate pressure on their overburdened correctional facilities. Over the 80 years more than 165,000 convicts were transported to Australia.

The number of convicts pales in comparison to the immigrants who arrived in Australia in the 1851–1871 gold rush. In 1852 alone, 370,000 immigrants arrived in Australia. By 1871 the total population had nearly quadrupled from 430,000 to 1.7 million people. The last convicts to be transported to Australia arrived in Western Australia in 1868. The convict transportation system has also been referred to as white slavery.

Reasons for transportation

Main article: Penal transportationPoverty, social injustice, child labor, harsh and dirty living conditions and long working hours were prevalent in 19th-century Britain. Dickens' novels perhaps best illustrate this; even some government officials were horrified by what they saw. Only in 1833 and 1844 were the first general laws against child labor (the Factory Acts) passed in the United Kingdom.

According to Robert Hughes in The Fatal Shore, the population of England and Wales, which had remained steady at 6 million from 1700 to 1740, rose dramatically after 1740. By the time of the American Revolution, London was overcrowded, filled with the unemployed, and flooded with cheap gin. Crime had become a major problem. In 1784 a French observer noted that "from sunset to dawn the environs of London became the patrimony of brigands for twenty miles around."

Each parish had a watchman, but Britain did not then have a police force as we know it. Jeremy Bentham avidly promoted the idea of a circular prison, but the penitentiary was seen by many government officials as a peculiarly American concept. Virtually all malefactors were caught by informers or denounced to the local court by their victims.

Due to the Bloody Code, by the 1770s, there were 222 crimes in Britain which carried the death penalty, almost all of them for crimes against property. Many even included offences such as the stealing of goods worth over 5 shillings, the cutting down of a tree, stealing an animal or stealing from a rabbit warren. The Bloody Code died out in the 1800s because judges and juries thought that punishments were too harsh. Since the law makers still wanted punishments to scare potential criminals, but needed them to become less harsh, transportation became the more common punishment.

The Industrial Revolution saw an increase in petty crime in Europe due to the displacement of much of the population, leading to pressures on the government to find an alternative to confinement in overcrowded gaols. The situation in Britain was so dire in fact, that hulks left over from the Seven Years War were used as makeshift floating prisons.

Transportation was a common punishment handed out for both major and petty crimes in Britain from the seventeenth century until well into the nineteenth century. At the time it was seen as a more humane alternative to execution. Around 60,000 convicts were transported to the British colonies in North America in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. When the American Revolutionary War brought an end to that means of disposal, the British Government was forced to look elsewhere. After James Cook's famous voyage to the South Pacific in which he visited and claimed the east coast of Australia in the name of the British Empire, he reported Botany Bay, a bay in modern day Sydney, as being the ideal place to establish a settlement. By 1788, the First Fleet arrived and the first British colony in Australia was established.

New South Wales

Main article: History of New South Wales

Alternatives to the American colonies were investigated and the newly discovered and mapped East Coast of New Holland was proposed. The details provided by James Cook during his expedition to the South Pacific in 1770 made it the most suitable.

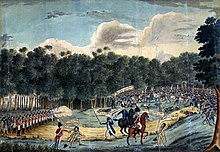

On 18 August 1786 the decision was made to send a colonisation party of convicts, military, and civilian personnel to Botany Bay. There were 775 convicts on board six transport ships. They were accompanied by officials, members of the crew, marines, the families thereof and their own children who together totaled 645. In all, eleven ships were sent in what became known as the First Fleet. Other than the convict transports, there were two naval escorts and three storeships. The fleet assembled in Portsmouth and set sail on 13 May 1787.

The fleet arrived at Botany Bay on 20 January 1788. It soon became clear that it would not be suitable for the establishment of a colony, and the group relocated to Port Jackson. There they established the first permanent European colony on the Australian continent, New South Wales, on 26 January. The area has since developed into Sydney. This date is still celebrated as Australia Day.

There was initially a high mortality rate amongst the members of the first fleet due mainly to shortages of food. The ships carried only enough food to provide for the settlers until they could establish agriculture in the region. Unfortunately, there were insufficient skilled farmers and domesticated livestock to do this, and the colony waited on the arrival of the Second Fleet. The second fleet was an unprecedented disaster that provided little in the way of help and upon its delivery in June 1790 of still more sick and dying convicts, which actually worsened the situation in Port Jackson.

Lieutenant-General Sir Richard Bourke was the ninth Governor of the Colony of New South Wales between 1831 and 1837. Appalled by the excessive punishments doled out to convicts, Bourke passed 'The Magistrates Act', which limited the sentence a magistrate could pass to fifty lashes (previously there was no such limit). Bourke's administration was controversial, and furious magistrates and employers petitioned the crown against this interference with their legal rights, fearing that a reduction in punishments would cease to provide enough deterrence to the convicts.

Bourke, however, was not dissuaded from his reforms and continued to create controversy within the colony by combating the inhumane treatment handed out to convicts, including limiting the number of convicts each employer was allowed to seventy, as well as granting rights to freed convicts, such as allowing the acquisition of property and service on juries. It has been argued that the suspension of convict transportation to New South Wales in 1840 can be attributed to the actions of Bourke and other men like Australian-born lawyer William Charles Wentworth. It took another 10 years, but transportation to the colony of New South Wales was finally officially abolished on 1 October 1850.

If a convict was well behaved, the convict could be given a ticket of leave, granting some freedom. At the end of the convict's sentence, seven years in most cases, the convict was issued with a Certificate of Freedom. He was then free to become a settler or to return to England. Convicts who misbehaved, however, were often sent to a place of secondary punishment like Port Arthur, Tasmania or Norfolk Island, where they would suffer additional punishment and solitary confinement.

Tasmania

In 1803, a British expedition was sent from Sydney to Tasmania (then known as Van Diemen's Land) to establish a new penal colony there. The small party, led by Lt. John Bowen, established a settlement at Risdon Cove, on the eastern side of the Derwent River. Originally sent to Port Philip, but abandoned within weeks, another expedition led by Lieutenant-Colonel David Collins arrived soon after. Collins considered the Risdon Cove site inadequate, and in 1804 he established an alternative settlement on the western side of the river at Sullivan's Cove, Tasmania. This later became known as Hobart, and the original settlement at Risdon Cove was abandoned. Collins became the first Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen's Land.

When the convict station on Norfolk Island was abandoned in 1807-8, the remaining convicts and free settlers were transported to Hobart and allocated land for re-settlement. However, as the existing small population was already experiencing difficulties producing enough food, the sudden doubling of the population was almost catastrophic.

Starting in 1816, more free settlers began arriving from Great Britain. On 3 December 1825 Tasmania was declared a colony separate from New South Wales, with a separate administration.

The Macquarie Harbour penal colony on the West Coast of Tasmania was established in 1820 to exploit the valuable timber Huon Pine growing there for furniture making and shipbuilding. Macquarie Harbour had the added advantage of being almost impossible to escape from, most attempts ending with the convicts either drowning, dying of starvation in the bush, or (on at least two occasions) turning cannibal. Convicts sent to this settlement had usually re-offended during their sentence of transportation, and were treated very harshly, labouring in cold and wet weather, and subjected to severe corporal punishment for minor infractions.

In 1830, the Port Arthur penal settlement was established to replace Macquarie Harbour, as it was easier to maintain regular communications by sea. Although known in popular history as a particularly harsh prison, in reality its management was far more humane than Macquarie Harbour or the outlying stations of New South Wales. Experimentation with the so-called model prison system took place in Port Arthur. Solitary confinement was the preferred method of punishment.

Many changes were made to the manner in which convicts were handled in the general population, largely responsive to British public opinion on the harshness or otherwise of their treatment. Until the late 1830s most convicts were either retained by Government for public works or assigned to private individuals as a form of indentured labour. From the early 1840s the Probation System was employed, where convicts spent an initial period, usually two years, in public works gangs on stations outside of the main settlements, then were freed to work for wages within a set district.

Transportation to Tasmania ended in 1853 (see section below on Cessation of Transportation).

Queensland

Main article: History of QueenslandIn 1823 John Oxley sailed north from Sydney to inspect Port Curtis and Moreton Bay as possible sites for a penal colony. At Moreton Bay he found the Brisbane River, which Cook had guessed would exist, and explored the lower part of it. In September 1824, he returned with soldiers and established a temporary settlement at Redcliffe. On 2 December 1824, the settlement was transferred to where the Central Business District (CBD) of Brisbane now stands. The settlement was at first called Edenglassie. In 1839 transportation of convicts to Moreton Bay ceased and the Brisbane penal settlement was closed. In 1842 free settlement was permitted and people began to colonize the area voluntarily. On 6 June 1859 Queensland became a colony separate from New South Wales.

Western Australia

Transportation of convicts to Western Australia began in 1850 and continued until 1868. During that period, 9,668 convicts were transported on 43 convict ships.

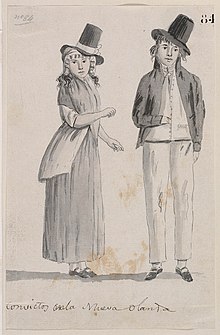

The first convicts to arrive in what is now Western Australia were convicts transported to New South Wales, and sent by that colony to King George Sound (Albany) in 1826 to help establish a settlement there. At that time the western third of Australia was unclaimed land known as New Holland. Fears that France would lay claim to the land prompted the Governor of New South Wales, Ralph Darling, to send Major Edmund Lockyer, with troops and 23 convicts, to establish a settlement at King George Sound. Lockyer's party arrived on Christmas Day, 1826. A convict presence was maintained at the settlement for nearly four years. In November 1830, control of the settlement was transferred to the Swan River Colony, and the troops and convicts were withdrawn.

In April 1848, Charles Fitzgerald, Governor of Western Australia, petitioned Britain to send convicts to Western Australia because of labor shortages. Britain rejected sending fixed term convicts, but offered to send first offenders in the final years of their terms.

Most convicts in Western Australia spent very little time in prison. Those who were stationed at Fremantle were housed in the Convict Establishment, the colony's convict prison, and misbehaviour was punished by stints there. The majority of convicts, however, were stationed in other parts of the colony. Although there was no convict assignment in Western Australia, there was a great demand for public infrastructure throughout the colony, so that many convicts were stationed in remote areas. Initially, most convicts were set to work creating infrastructure for the convict system, including the construction of the Convict Establishment itself.

In 1852 a Convict Depot was built at Albany, but closed 3 years later. When shipping increased the Depot was re-opened. Most of the convicts had their Ticket-of-Leave and were hired to work by the free settlers. Convicts also manned the pilot boat, rebuilt York Street and Stirling Terrace; and the track from Albany to Perth was made into a good road. An Albany newspaper noted the convict's good behaviour and wrote, "There were instances in which our free settlers might take an example".

Western Australia's convict era came to an end with the cessation of penal transportation by Britain. In May 1865, the colony was advised of the change in British policy, and told that Britain would send one convict ship in each of the years 1865, 1866 and 1867, after which transportation would cease. In accordance with this, the last convict ship to Western Australia, the Hougoumont, left Britain in 1867 and arrived in Western Australia on 10 January 1868.

Victoria

In 1803 two ships arrived in Port Phillip, which Lt. John Murray in the Lady Nelson had discovered and named the previous year. The Calcutta under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Collins transported 300 convicts, accompanied by the supply ship, Ocean. Collins had previously been Judge Advocate with the First Fleet in 1788. He chose Sullivan Bay near the present-day Sorrento, Victoria for the first settlement - some 90 km south east of present-day Melbourne. About two months later the settlement was abandoned due to poor soil and water shortages and Collins moved the convicts to Hobart. Several convicts had escaped into the bush and were left behind to unknown fates with the hostile local aboriginal people. One such convict, the subsequently celebrated William Buckley, lived in the western side of Port Phillip for the next 32 years before approaching the new settlers and assisting as an interpreter for the indigenous peoples. A second settlement was established at Westernport Bay, on the site of present-day Corinella, in November 1826. It comprised an initial 20 soldiers and 22 convicts, with another 12 convicts arriving subsequently. This settlement was abandoned in February 1828, and all convicts returned to Sydney.

The Port Phillip District was officially sanctioned in 1837 following the landing of the Henty brothers in Portland Bay in 1834, and John Batman settled on the site of Melbourne.

Between 1844 and 1849 about 1,750 convicts arrived there from England. They were referred to either as "Exiles" or the "Pentonvillians" because most of them came from Pentonville Probationary Prison. Unlike earlier convicts who were required to work for the government or on hire from penal depots, the Exiles were free to work for pay, but could not leave the district to which they were assigned. The Port Phillip District was still part of New South Wales at this stage. Victoria separated from New South Wales and became an independent colony in 1851.

Women

Main article: Convict Women in AustraliaApproximately 20% of the transportees were women, for whom conditions could be particularly harsh. For protection, most quickly attached themselves to male officers or convicts. Although they were routinely referred to as courtesans relatively few had been prostitutes in England; prostitution, like murder, was not a transportable offense.

Political prisoners

Political prisoners made up a small proportion of convicts. They arrived in waves corresponding to political unrest in Britain and Ireland. They included the First Scottish Martyrs in 1794; British Naval Mutineers (from the Nore Mutiny) in 1797 and 1801; Irish rebels in 1798, 1803, 1848 and 1868; Scots Rebels (1820); Yorkshire Rebels (1820 and 1822); leaders of the Merthyr Tydfil rising of 1831; The Tolpuddle Martyrs (1834); Swing Rioters and Machine Breakers (1828–1833); Upper Canada rebellion/Lower Canada Rebellion (1839) and Chartists (1842).

Cessation of transportation

With increasing numbers of free settlers entering New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) by the mid-1830s, opposition to the transportation of felons into the colonies grew. The most influential spokesmen were newspaper proprietors who were also members of the Independent Congregation Church such as John Fairfax in Sydney and the Reverend John West in Launceston, who argued against convicts both as competition to honest free labourers and as the source of crime and vice within the colony. The anti-transportation movement was seldom concerned with the inhumanity of the system, but rather the hated stain it was believed to inflict on the free (non-emancipist) middle classes.

Transportation to New South Wales ended in 1840, by which time some 150,000 convicts had been sent to the colonies. The sending of convicts to Brisbane in its Moreton Bay district had ceased the previous year, and administration of Norfolk Island was later transferred to Van Diemen's Land.

The continuation of transportation to Van Diemen's Land saw the rise of a well-coordinated anti- transportation movement, especially following a severe economic depression in the early 1840s. Transportation was temporarily suspended in 1846 but soon revived with overcrowding of British gaols and clamour for the availability of transportation as a deterrent. By the late 1840s most convicts being sent to Van Diemen's Land (plus those to Victoria) were designated as "exiles" and were free to work for pay while under sentence. In 1850 the Australasian Anti-Transportation League was formed to lobby for the permanent cessation of transportation, its aims being furthered by the commencement of the Australian gold rushes the following year. The last convict ship to be sent from England, the St. Vincent, arrived in 1853, and on 10 August 1853 Jubilee festivals in Hobart and Launceston celebrated 50 years of European settlement with the official end of transportation.

Transportation continued in small numbers to Western Australia. The last convict ship to arrive in Western Australia, the Hougoumont, left Britain in 1867 and arrived in Western Australia on 10 January 1868. In all, about 164,000 convicts were transported to the Australian colonies between 1788 and 1868 on board 806 ships. Convicts were made up of English and Welsh (70%), Irish (24%), Scottish (5%) and the remaining 1% from the British outposts in India and Canada, Maoris from New Zealand, Chinese from Hong Kong and slaves from the Caribbean.

Only South Australia and the Northern Territory had never accepted convicts directly from England but they still accepted ex-convicts from the other states. Many convicts were allowed to travel as far as New Zealand to make a new life after being given limited freedom, even if they were not allowed to return home to England. At this time the Australian population was approximately 1 million and the colonies could now sustain themselves without the need for convict labour.

Notable convicts transported to Australia

- Esther Abrahams – British Jew, who was one of the Jewish convicts (about 1,000 in all) and common law wife of a leader of the Rum Rebellion.

- Samuel Barsby – first convict to be flogged

- Billy Blue – black Jamaican, established a ferry service

- James Blackburn – Famous for contribution to Australian architecture and civil engineering

- William Bland – naval surgeon transported for killing a man in a duel; he prospered and was involved in philanthropy, and had a seat in the legislative assembly.

- Mary Bryant – famous escapee

- William Buckley – famously escaped and lived with Aboriginal people for many years

- John Cadman – had been a publican, as a convict became Superintendent of Boats in Sydney; Cadmans Cottage is a cottage granted to him.

- Martin Cash – Famous escapee and bushranger

- Nicholas Troja – Disgraced, moved to London

- William Chopin – a convict whose work in prison hospitals in Western Australia grounded him in chemistry; on receiving a ticket of leave he was appointed chemist at the Colonial Hospital, but preferred to open his own chemist shop. He was later convicted as an abortionist.

- Daniel Connor – successful merchant.

- Daniel Cooper – successful merchant.

- William Cuffay (convict and tailor) – Black London Chartist leader who became an important workers' rights leader in Hobart.

- John Davies – co-founded The Mercury newspaper.

- Margaret Dawson – First Fleeter, "founding mother"

- John Eyre – painter and engraver

- William Field (Australian pastoralist) – notable Tasmanian businessman and landowner

- Francis Greenway – famous Australian architect

- William Henry Groom – successful auctioneer and politician, served in the inaugural Australian Parliament.

- Laurence Hynes Halloran – founded Sydney Grammar School.

- William Hutchinson – public servant and pastoralist.

- John Irving – doctor transported on First Fleet, was the first convict to receive an absolute pardon.

- Mark Jeffrey – wrote famous autobiography

- Jørgen Jørgensen – eccentric Danish adventurer influenced by revolutionary ideas who declared himself ruler of Iceland, later became a spy in Britain.

- Henry Kable – First Fleet convict, arrived with wife and son (Susannah Holmes, also a convict, and Henry) filed 1st law suit in Australia, became wealthy businessman

- Lawrence Kavenagh – notorious bushranger

- John (Red) Kelly – Irish convict & father of bushranger Ned Kelly

- Solomon Levey – wealthy merchant, endowed Sydney Grammar School.

- Simeon Lord – pioneer merchant and magistrate in Australia

- Nathaniel Lucas – one of first convicts on Norfolk Island, where he became Master carpenter, later farmed successfully, built windmills, and was Superintendent of carpenters in Sydney.

- John Mitchel – Irish nationalist

- Francis "Frank the Poet" McNamara – composer of various oral convict ballads, including The Convict's Tour to Hell

- John Mortlock – former marine

- Thomas Muir – convicted of sedition for advocating parliamentary reform; escaped from N.S.W and after many vicissitudes made his way to revolutionary France.

- Isaac Nichols – entrepreneur, first Postmaster

- Kevin Izod O'Doherty – Medical student, Young Irelander who was transported for treason.

- Robert Palin – once in Australia, committed further crimes, and managed to be executed for a non-capital offence

- Alexander Pearce – cannibal escapee

- Joseph Potaskie – first Polish Jew to come to Australia.

- William Smith O'Brien – famous Irish revolutionary; sent to Van Diemen's Land in 1849 after leading a rebellion in Tipperary

- John Boyle O'Reilly – Famous escapee and writer; author of The Moondyne

- William Redfern – one of the few surgeon convicts

- Mary Reibey – operated a fleet of ships

- James Ruse – successful farmer

- Henry Savery – Australia's first novelist; author of Quintus Servinton

- Robert Sidaway – opened Australia's first theatre

- James Squire – English Romanichal (Romany) – First Fleet convict and Australia's first brewer and cultivator of hops.

- William Sykes – historically interesting because he left a brief diary and a bundle of letters.

- John Tawell – served his sentence, became a prosperous chemist, returned to England after 15 years, and after some time murdered a mistress, for which he was hanged.

- Samuel Terry – wealthy merchant and philanthropist.

- James Hardy Vaux – author of Australia's first full length autobiography and dictionary.

- Mary Wade – Youngest female convict transported to Australia (11 years of age) who had 21 children and at the time of her death had over 300 living descendants.

- Joseph Wild – explorer

- Solomon Wiseman – merchant and operated ferry on Hawkesbury River hence town name Wisemans Ferry.

See also

- British prison hulks

- Convicts on the West Coast of Tasmania

- Convict era of Western Australia

- Convict assignment

- Convict women in Australia

- Convict hulk

- French ship Neptune (1818)

- First Fleet

- List of convicts on the First Fleet

- Port Arthur, Tasmania

- Transport Board

- Unfree labour

Sources

- Alan Frost, Botany Bay: The Real Story, Collingwood, Black Inc, 2011, ISBN 978-1-86395-512-6

- Alexander, Alison. Editor. The Companion to Tasmanian History. Hobart, 2005. ISBN 1-86295-223-X

- Bateson, Charles, The Convict Ships, 1787–1868, Sydney, 1974.

- Pardons & Punshments: Judge's Reports on Criminals, 1783 to 1830: HO (Home Office) 47, volumes 304 & 305, List and Index Society, The National Archives, Kew, England, TW9 4DU

- Gillen, Mollie, The Founders of Australia: a biographical dictionary of the First Fleet, Sydney, Library of Australian History, 1989.

- Gordon Greenwood, Australia: A Social and Political History, Angus and Robertson 1955.

- Hughes, Robert, The Fatal Shore, London, Pan, 1988.

- A Pictorial History of Australia, Rex & Thea Rienits, Hamlyn Publishing group, 1969.

- Robson, Lloyd. History of Tasmania, 2 Volumes.

- Edward Shann, An Economic History of Australia, Georgian House 1930.

- John West, History of Tasmania, 1852

References

- Convict Records

- http://www.cultureandrecreation.gov.au/articles/goldrush/

- "The Life of the Industrial Worker in Ninteenth-Century England".

- Gin Epidemic – 1720–1750

- Highes, ibid, p. 28

- Part I: History of the Death Penalty

- By the Gallows

- The Floating Prison: British Prison Hulks

- Convict Labour

- Convicts

- "The Westernport Settlement of 1826–28"

- Hughes, ibid, p372

- Guide to Researching your convict ancestors

- Convicts and the British colonies in Australia

- Kirby, Michael review of Collins, the Courts and The Colony, UNSW Press, 1996. on Law and Justice Foundation of New South Wales website

- D. Richards 'Transported to New South Wales: medical convicts 1788–1850' British Medical Journal Vol 295, 19–26 December 1987, p. 1609

External links

- Family History Convicts Research Guide – State Library of New South Wales

- Convict life – State Library of New South Wales

- Australian Convict Transportation Registers

- The National Archives (UK)

- Convict Transportation Registers database

- The Albany Historical Society

- Convict Queenslanders

- Thomas J. Nevin's photographs of Tasmanian convicts 1870s at the State Library of Tasmania

- Thomas J. Nevin's photographs of Tasmanian convicts at the National Library of Australia

- Visualisation of the British Convict Transportation Registry

- The Convict Stockade

Categories: