| Revision as of 15:47, 26 July 2013 view sourceSb101 (talk | contribs)1,126 edits →Health care cost trends (health care cost inflation)← Previous edit | Revision as of 17:05, 26 July 2013 view source Prototime (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers8,440 edits tweaks/copy-editTags: nowiki added Visual editNext edit → | ||

| Line 172: | Line 172: | ||

| ===Effective by October 1, 2013=== | ===Effective by October 1, 2013=== | ||

| * |

* Individuals can enroll in subsidized health insurance plans offered through state-based health insurance exchanges. Coverage begins on January 1, 2014.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://money.cnn.com/2013/04/23/news/economy/obamacare-subsidies/index.html?hpt=hp_t5|title=Millions eligible for Obamacare subsidies, but most don't know it|author=]}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.kff.org/healthreform/upload/8213-2.pdf|title=ESTABLISHING HEALTH INSURANCE EXCHANGES: AN OVERVIEW OF STATE EFFORTS}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.healthcare.gov/marketplace/get-ready/index.html|title=Enrollment in the Marketplace starts in October 2013.}}</ref> | ||

| ===Effective by January 1, 2014=== | ===Effective by January 1, 2014=== | ||

| Line 178: | Line 178: | ||

| ] and ].<ref name="private_pp" /> (Source: ])]] | ] and ].<ref name="private_pp" /> (Source: ])]] | ||

| * Insurers are prohibited from discriminating against or charging higher rates for any individual based on |

* Insurers are prohibited from discriminating against or charging higher rates for any individual based on pre-existing medical conditions or gender.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nh.gov/insurance/consumers/documents/naic_faq.pdf|title=I have been denied coverage because I have a pre-existing condition. What will this law do for me?|publisher=New Hampshire Insurance Department|work=Health Care Reform Frequently Asked Questions|accessdate=2012-06-28|page=2}}</ref> | ||

| * Insurers are prohibited from establishing annual spending caps.<ref name='Top 18' /> | * Insurers are prohibited from establishing annual spending caps.<ref name='Top 18' /> | ||

| * |

* Under the ], individuals who are not covered by an acceptable insurance policy will be charged an annual penalty of $95, or up to 1% of income over the filing minimum,<ref name=jct>"Generally, in 2010, the filing threshold is $9,350 for a single person or a married person filing separately and is $18,700 for married filing jointly." - Congress of the United States The Joint Committee on Taxation, "," March 21, 2010.</ref> whichever is greater; this will rise to a minimum of $695 ($2,085 for families),<ref>{{cite news|last=Doyle|first=Brion B.|title=Understanding the Impacts of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act|url=http://www.natlawreview.com/article/understanding-impacts-patient-protection-and-affordable-care-act|accessdate=17 April 2013|newspaper=The National Law Review|date=March 5, 2013|author2=Varnum LLP}}</ref> or 2.5% of income over the filing minimum,<ref name="jct" /> by 2016.<ref name="ksr_hlth" /><ref name = bglobetaximp>{{cite news|url=http://www.boston.com/business/personalfinance/managingyourmoney/archives/2010/03/tax_implication.html|title=Tax implications of health care reform legislation|author=Downey, Jamie|date=March 24, 2010|newspaper=]|accessdate=2010-03-25}}</ref> Exemptions are permitted for religious reasons, members of ], or for those for whom the least expensive policy would exceed 8% of their income.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/ezra-klein/post/individual-mandate-101-what-it-is-why-it-matters/2011/08/25/gIQAhPzCeS_blog.html|title=Individual mandate 101: What it is, why it matters |publisher=Wonkblog at the Washington Post|coauthors=Sarah Kliff; Ezra Klein|date=March 27, 2012|accessdate=July 2, 2012}}</ref> In 2010, the Commissioner speculated that insurance providers would supply a form confirming essential coverage to both individuals and the IRS; individuals would attach this form to their Federal tax return. Those who aren't covered will be assessed the penalty on their Federal tax return. In the wording of the law, a taxpayer who fails to pay the penalty "shall not be subject to any criminal prosecution or penalty", and cannot have liens or levies placed on their property, but the IRS will be able to withhold future tax refunds from them.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://money.cnn.com/2012/06/29/pf/taxes/health_insurance_mandate/index.htm|title=How health insurance mandate will work |publisher=CNN|author=Jeanne Sahadi|date=June 29, 2012|accessdate=July 12, 2013}}</ref> | ||

| * In participating states, Medicaid eligibility is expanded; all individuals with income up to 133% of the ] qualify for coverage, including adults without dependent children |

* In participating states, Medicaid eligibility is expanded; all individuals with income up to 133% of the ] qualify for coverage, including adults without dependent children.<ref name="ksr_hlth">{{cite news|url=http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/Stories/2010/March/22/consumers-guide-health-reform.aspx|first=Phil |last=Galewitz|title=Consumers Guide To Health Reform|date=March 26, 2010|newspaper=Kaiser Health News}}</ref><ref name="cnn_ref1">{{cite news|url=http://www.cnn.com/2010/HEALTH/03/25/health.care.law.basics/index.html|title=5 key things to remember about health care reform|publisher=CNN|date=March 25, 2010 | accessdate=May 21, 2010}}</ref> The law also provides for a 5% "income disregard", making the effective income eligibility limit 138% of the poverty line.<ref name="APHA138">{{cite web|title=Medicaid Expansion|url=http://www.apha.org/APHA/CMS_Templates/GeneralArticle.aspx?NRMODE=Published&NRNODEGUID=%7bD5E1C04A-0438-4FD4-A423-CEFDA0D9878D%7d&NRORIGINALURL=%2fadvocacy%2fHealth%2bReform%2fACAbasics%2fmedicaid%2ehtm|work=American Public Health Association (APHA)|accessdate=24 July 2013|location=Is Medicaid eligibility expanding to 133 or 138 percent FPL, and what is MAGI?}}</ref> Participating states may choose to increase the income eligibility limit beyond this minimum requirement.<ref name="APHA138">{{cite web|title=Medicaid Expansion|url=http://www.apha.org/APHA/CMS_Templates/GeneralArticle.aspx?NRMODE=Published&NRNODEGUID=%7bD5E1C04A-0438-4FD4-A423-CEFDA0D9878D%7d&NRORIGINALURL=%2fadvocacy%2fHealth%2bReform%2fACAbasics%2fmedicaid%2ehtm|work=American Public Health Association (APHA)|accessdate=24 July 2013|location=Is Medicaid eligibility expanding to 133 or 138 percent FPL, and what is MAGI?}}</ref> As written, the ACA withheld ''all'' Medicaid funding from states declining to participate in the expansion. However, the Supreme Court ruled in ''] ''(2012) that this withdrawal of funding was unconstitutionally coercive and that individual states had the right to opt out of the Medicaid expansion without losing ''pre-existing'' Medicaid funding from the federal government. As of April 25, 2013, fifteen states—], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]—were not participating in the Medicaid expansion, with ten more—], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]—leaning towards not participating.<ref>Kliff, Sarah. (2013-04-25) . Washingtonpost.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-17.</ref> | ||

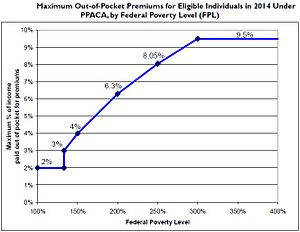

| *]s are established, and subsides for insurance premiums are given to individuals who buy a plan from an exchange and have a household income between 133% and 400% of the poverty line.<ref name="cnn_ref1" /><ref>{{cite web|title=Health Insurance Premium Credits Under PPACA (P.L. 111-148)|url=http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/economics/uploads/docs/jeanabrahamcrscredits.pdf|publisher=Congressional Research Service|author=Chris L. Peterson, Thomas Gibe|date=April 6, 2010}}</ref><ref name='Galewitz'>{{cite news | first=Phil | last=Galewitz | title=Health reform and you: A new guide | date=2010-03-22 | publisher=] | url =http://today.msnbc.msn.com/id/34609984/ns/health-health_care/ | accessdate = 2010-03-23 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Politics/2010/0320/Health-care-reform-bill-101-Who-gets-subsidized-insurance|title=Health Care Reform Bill 101|work=]}}</ref> Section 1401(36B) of PPACA explains that each subsidy will be provided as an advanceable, ]<ref name=sec1401>{{cite web|url=http://en.wikisource.org/Patient_Protection_and_Affordable_Care_Act/Title_I/Subtitle_E/Part_I/Subpart_A|title=Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act/Title I/Subtitle E/Part I/Subpart A}}</ref> and gives a formula for its calculation.<ref name=sec1401_p>]</ref> A ] is a way to provide government benefits to individuals who may have no tax liability<ref>{{cite web|url=http://hungerreport.org/2010/report/chapters/two/taxes/refundable-tax-credits|title=Refundable Tax Credit}}</ref> (such as the ]). The formula was changed in the amendments (HR 4872) passed March 23, 2010, in section 1001. To qualify for the subsidy, the beneficiaries cannot be eligible for other acceptable coverage. The ] (DHHS) and ] (IRS) on May 23, 2012, issued joint final rules regarding implementation of the new state-based health insurance exchanges to cover how the exchanges will determine eligibility for uninsured individuals and employees of small businesses seeking to buy insurance on the exchanges, as well as how the exchanges will handle eligibility determinations for low-income individuals applying for newly expanded Medicaid benefits.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2012-05-23/pdf/2012-12421.pdf|title=Health Insurance Premium Tax Credit – from DHHS and IRS}}</ref><ref name="treasury_12">{{cite web|url=http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/Documents/36BFactSheet.PDF|title=Treasury Lays the Foundation to Deliver Tax Credits}}</ref> According to ] and ], in 2014 the income-based premium caps for a ] for a family of four will be the following: | *]s are established, and subsides for insurance premiums are given to individuals who buy a plan from an exchange and have a household income between 133% and 400% of the poverty line.<ref name="cnn_ref1" /><ref>{{cite web|title=Health Insurance Premium Credits Under PPACA (P.L. 111-148)|url=http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/economics/uploads/docs/jeanabrahamcrscredits.pdf|publisher=Congressional Research Service|author=Chris L. Peterson, Thomas Gibe|date=April 6, 2010}}</ref><ref name='Galewitz'>{{cite news | first=Phil | last=Galewitz | title=Health reform and you: A new guide | date=2010-03-22 | publisher=] | url =http://today.msnbc.msn.com/id/34609984/ns/health-health_care/ | accessdate = 2010-03-23 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Politics/2010/0320/Health-care-reform-bill-101-Who-gets-subsidized-insurance|title=Health Care Reform Bill 101|work=]}}</ref> Section 1401(36B) of PPACA explains that each subsidy will be provided as an advanceable, ]<ref name=sec1401>{{cite web|url=http://en.wikisource.org/Patient_Protection_and_Affordable_Care_Act/Title_I/Subtitle_E/Part_I/Subpart_A|title=Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act/Title I/Subtitle E/Part I/Subpart A}}</ref> and gives a formula for its calculation.<ref name=sec1401_p>]</ref> A ] is a way to provide government benefits to individuals who may have no tax liability<ref>{{cite web|url=http://hungerreport.org/2010/report/chapters/two/taxes/refundable-tax-credits|title=Refundable Tax Credit}}</ref> (such as the ]). The formula was changed in the amendments (HR 4872) passed March 23, 2010, in section 1001. To qualify for the subsidy, the beneficiaries cannot be eligible for other acceptable coverage. The ] (DHHS) and ] (IRS) on May 23, 2012, issued joint final rules regarding implementation of the new state-based health insurance exchanges to cover how the exchanges will determine eligibility for uninsured individuals and employees of small businesses seeking to buy insurance on the exchanges, as well as how the exchanges will handle eligibility determinations for low-income individuals applying for newly expanded Medicaid benefits.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2012-05-23/pdf/2012-12421.pdf|title=Health Insurance Premium Tax Credit – from DHHS and IRS}}</ref><ref name="treasury_12">{{cite web|url=http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/Documents/36BFactSheet.PDF|title=Treasury Lays the Foundation to Deliver Tax Credits}}</ref> According to ] and ], in 2014 the income-based premium caps for a ] for a family of four will be the following: | ||

| {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 1em auto 1em auto" | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 1em auto 1em auto" | ||

| Line 335: | Line 335: | ||

| With ] as one of the stated goals of the Obama Administration, Congressional Democrats and health policy experts like ] and ] argued that ] would require both a (partial) ] and an ] to prevent either ] and/or ] from creating an ].<ref name=Mandate1>{{cite web|author=Jonathan Cohn |url=http://www.newrepublic.com/article/75077/how-they-did-it |title=How They Did It |publisher=The New Republic |date=2010-05-21 }}</ref> They convinced Obama that this was necessary, which persuaded the Administration to accept Congressional proposals that included a mandate.<ref name=Mandate2>{{cite web|author=Jonathan Cohn |url=http://www.newrepublic.com/blog/the-treatment/the-top-ten-things-worth-fighting |title=The Top Ten Things Worth Fighting For |publisher=The New Republic |date=2009-10-13 }}</ref> This approach was preferred because the President and Congressional leaders concluded that more liberal plans (such as ]) could not win filibuster-proof support in the Senate. By deliberately drawing on bipartisan ideas - the same basic outline was supported by former Senate Majority Leaders ], ], ] and ] - the bill's drafters hoped to increase the chances of getting the necessary votes for passage.<ref>{{cite web|author=Jonathan Cohn |url=http://www.newrepublic.com/article/health-care/party-is-such-sweet-sorrow |title=Party Is Such Sweet Sorrow |publisher=The New Republic |date=2009-09-04 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|author=Jonathan Chait |url=http://www.newrepublic.com/blog/jonathan-chait/obamas-moderate-health-care-plan |title=Obama's Moderate Health Care Plan |publisher=The New Republic |date=2010-04-22 }}</ref><ref name="newrepublic1">{{cite web|author=Jonathan Chait |url=http://www.newrepublic.com/blog/the-plank/the-republican-health-care-blunder |title=The Republican Health Care Blunder |publisher=The New Republic |date=2009-12-19 }}</ref> | With ] as one of the stated goals of the Obama Administration, Congressional Democrats and health policy experts like ] and ] argued that ] would require both a (partial) ] and an ] to prevent either ] and/or ] from creating an ].<ref name=Mandate1>{{cite web|author=Jonathan Cohn |url=http://www.newrepublic.com/article/75077/how-they-did-it |title=How They Did It |publisher=The New Republic |date=2010-05-21 }}</ref> They convinced Obama that this was necessary, which persuaded the Administration to accept Congressional proposals that included a mandate.<ref name=Mandate2>{{cite web|author=Jonathan Cohn |url=http://www.newrepublic.com/blog/the-treatment/the-top-ten-things-worth-fighting |title=The Top Ten Things Worth Fighting For |publisher=The New Republic |date=2009-10-13 }}</ref> This approach was preferred because the President and Congressional leaders concluded that more liberal plans (such as ]) could not win filibuster-proof support in the Senate. By deliberately drawing on bipartisan ideas - the same basic outline was supported by former Senate Majority Leaders ], ], ] and ] - the bill's drafters hoped to increase the chances of getting the necessary votes for passage.<ref>{{cite web|author=Jonathan Cohn |url=http://www.newrepublic.com/article/health-care/party-is-such-sweet-sorrow |title=Party Is Such Sweet Sorrow |publisher=The New Republic |date=2009-09-04 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|author=Jonathan Chait |url=http://www.newrepublic.com/blog/jonathan-chait/obamas-moderate-health-care-plan |title=Obama's Moderate Health Care Plan |publisher=The New Republic |date=2010-04-22 }}</ref><ref name="newrepublic1">{{cite web|author=Jonathan Chait |url=http://www.newrepublic.com/blog/the-plank/the-republican-health-care-blunder |title=The Republican Health Care Blunder |publisher=The New Republic |date=2009-12-19 }}</ref> | ||

| However, following the adoption of an individual mandate as a central component of the proposed reforms by Democrats, Republicans began to oppose the mandate and threaten to filibuster any bills that contained it.<ref name="forbes1"/> Senate Minority Leader ], who lead the Republican Congressional strategy in responding to the bill, calculated that Republicans should not support the bill, and worked to keep party discipline and prevent defections:<ref name="newrepublic1"/>{{cquote|It was absolutely critical that everybody be together because if the proponents of the bill were able to say it was bipartisan, it tended to convey to the public that this is O.K., they must have figured it out.<ref>{{cite news|author=Carl Hulse and Adam Nagourney |url=http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/17/us/politics/17mcconnell.html?pagewanted=1&hp |title=Senate G.O.P. Leader Finds Weapon in Unity |publisher=The New York Times |date=2010-03-16 }}</ref>}} Republican Senators (including those who had supported previous bills with a similar mandate) began to describe the mandate as "unconstitutional". Writing in '']'', Ezra Klein stated that "the end result was... a policy that once enjoyed broad support within the Republican Party suddenly faced unified opposition."<ref name="new-yorker-klein"/> The '']'' subsequently noted: "It can be difficult to remember now, given the ferocity with which many Republicans assail it as an attack on freedom, but the provision in President Obama's health care law requiring all Americans to buy health insurance has its roots in conservative thinking."<ref name="nyt-mandate"/><ref name="politifact1993"/> | However, following the adoption of an individual mandate as a central component of the proposed reforms by Democrats, Republicans began to oppose the mandate and threaten to filibuster any bills that contained it.<ref name="forbes1"/> Senate Minority Leader ], who lead the Republican Congressional strategy in responding to the bill, calculated that Republicans should not support the bill, and worked to keep party discipline and prevent defections:<ref name="newrepublic1"/>{{cquote|It was absolutely critical that everybody be together because if the proponents of the bill were able to say it was bipartisan, it tended to convey to the public that this is O.K., they must have figured it out.<ref>{{cite news|author=Carl Hulse and Adam Nagourney |url=http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/17/us/politics/17mcconnell.html?pagewanted=1&hp |title=Senate G.O.P. Leader Finds Weapon in Unity |publisher=The New York Times |date=2010-03-16 }}</ref>}} | ||

| <nowiki> </nowiki>Republican Senators (including those who had supported previous bills with a similar mandate) began to describe the mandate as "unconstitutional". Writing in '']'', Ezra Klein stated that "the end result was... a policy that once enjoyed broad support within the Republican Party suddenly faced unified opposition."<ref name="new-yorker-klein"/> The '']'' subsequently noted: "It can be difficult to remember now, given the ferocity with which many Republicans assail it as an attack on freedom, but the provision in President Obama's health care law requiring all Americans to buy health insurance has its roots in conservative thinking."<ref name="nyt-mandate"/><ref name="politifact1993"/> | |||

| ], September 12, 2009.]] | ], September 12, 2009.]] | ||

| Line 500: | Line 501: | ||

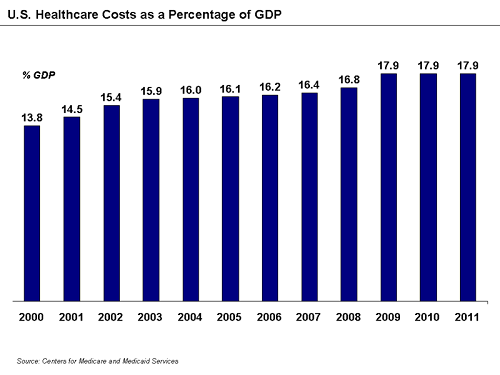

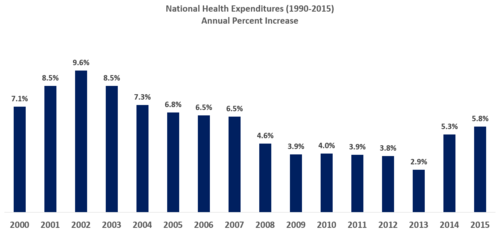

| ====Health care cost trends (health care cost inflation)==== | ====Health care cost trends (health care cost inflation)==== | ||

| In a May 2010 presentation on "Health Costs and the Federal Budget", CBO stated:{{cquote|Rising health costs will put tremendous pressure on the federal budget during the next few decades and beyond. In CBO's judgment, the health legislation enacted earlier this year does not substantially diminish that pressure.}} CBO further observed that "a substantial share of current spending on health care contributes little if anything to people's health" and concluded, "Putting the federal budget on a sustainable path would almost certainly require a significant reduction in the growth of federal health spending relative to current law (including this year's health legislation)."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/115xx/doc11544/Presentation5-26-10.pdf |title=Health Costs and the Federal Budget |publisher=Congressional Budget Office |date=May 28, 2010 |accessdate=April 1, 2012}}</ref> | In a May 2010 presentation on "Health Costs and the Federal Budget", CBO stated:{{cquote|Rising health costs will put tremendous pressure on the federal budget during the next few decades and beyond. In CBO's judgment, the health legislation enacted earlier this year does not substantially diminish that pressure.}} | ||

| <nowiki> </nowiki>CBO further observed that "a substantial share of current spending on health care contributes little if anything to people's health" and concluded, "Putting the federal budget on a sustainable path would almost certainly require a significant reduction in the growth of federal health spending relative to current law (including this year's health legislation)."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/115xx/doc11544/Presentation5-26-10.pdf |title=Health Costs and the Federal Budget |publisher=Congressional Budget Office |date=May 28, 2010 |accessdate=April 1, 2012}}</ref> | |||

| ], a noted health policy analyst, commented that: {{cquote|CBO doesn't produce estimates of how reform will affect overall health care spending--that is, the amount of money our society, as a whole, will devote to health care. But the official ] does. The actuary determined that... the long-term trend is towards less spending: Inflation after ten years would be lower than it is now. And it's the long-term trend that matters most... will reduce the cost of care--not by a lot and not by as much as possible in theory, but as much as is possible in this political universe.<ref name=CohnCostControl /><ref>{{cite news |title=New Cost Estimate on Senate Bill |author=Jonathan Cohn |publisher=The New Republic |date=December 11, 2009 |url=http://www.tnr.com/blog/the-treatment/breaking-new-cost-estimate-senate-bill }}</ref>}} He and fellow '']'' editor ] further noted the CBO didn't include in its estimate various cost-saving provisions intended to reduce health inflation,<ref name=CBOMethodology>{{cite news |title=The GOP's Trick Play |author=Jonathan Cohn |publisher=The New Republic |date=January 21, 2011 |url=http://www.tnr.com/blog/jonathan-cohn/81941/trick-play }}</ref> and that historically the CBO has consistently underestimated the impact of health legislation.<ref name=CBOTrackRecord>{{cite news |title=Is the CBO Biased Against Health Care Reform? |author=Noam Scheiber |publisher=The New Republic |date=September 17, 2009 |url=http://www.tnr.com/blog/the-stash/the-cbo-biased-against-health-care-reform }}</ref> | ], a noted health policy analyst, commented that: {{cquote|CBO doesn't produce estimates of how reform will affect overall health care spending--that is, the amount of money our society, as a whole, will devote to health care. But the official ] does. The actuary determined that... the long-term trend is towards less spending: Inflation after ten years would be lower than it is now. And it's the long-term trend that matters most... will reduce the cost of care--not by a lot and not by as much as possible in theory, but as much as is possible in this political universe.<ref name=CohnCostControl /><ref>{{cite news |title=New Cost Estimate on Senate Bill |author=Jonathan Cohn |publisher=The New Republic |date=December 11, 2009 |url=http://www.tnr.com/blog/the-treatment/breaking-new-cost-estimate-senate-bill }}</ref>}} | ||

| <nowiki> </nowiki>He and fellow '']'' editor ] further noted the CBO didn't include in its estimate various cost-saving provisions intended to reduce health inflation,<ref name=CBOMethodology>{{cite news |title=The GOP's Trick Play |author=Jonathan Cohn |publisher=The New Republic |date=January 21, 2011 |url=http://www.tnr.com/blog/jonathan-cohn/81941/trick-play }}</ref> and that historically the CBO has consistently underestimated the impact of health legislation.<ref name=CBOTrackRecord>{{cite news |title=Is the CBO Biased Against Health Care Reform? |author=Noam Scheiber |publisher=The New Republic |date=September 17, 2009 |url=http://www.tnr.com/blog/the-stash/the-cbo-biased-against-health-care-reform }}</ref> | |||

| ], an influential consultant who helped develop both the Affordable Care Act and the Massachusetts Health Care reform that preceded it, acknowledges that the Affordable Care Act is not ''guaranteed'' to significantly 'bend the curve' of rising health care costs:<ref>{{cite book|last=Gruber|first=Jonathan|title=Health Care Reform: What It Is, Why It's Necessary, How It Works|year=2011|publisher=Hill and Wang|location=United States|isbn=978-0-8090-5397-1|page=101}}</ref>{{cquote|The real question is how far the ACA will go in slowing cost growth. Here, there is great uncertainty—mostly because there is such uncertainty in general about how to control cost growth in health care. There is no shortage of good ideas for ways of doing so... There is, however, a shortage of evidence regarding which approaches will actually work—and therefore no consensus on which path is best to follow. In the face of such uncertainty, the ACA pursued the path of considering a range of different approaches to controlling health care costs... Whether these policies by themselves can fully solve the long run health care cost problem in the United States is doubtful. They may, however, provide a first step towards controlling costs—and understanding what does and does not work to do so more broadly.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://economics.mit.edu/files/6829 |last=Gruber|first=Jonathan|title=The Impacts Of The Affordable Care Act: How Reasonable Are The Projections?}}</ref>}} | ], an influential consultant who helped develop both the Affordable Care Act and the Massachusetts Health Care reform that preceded it, acknowledges that the Affordable Care Act is not ''guaranteed'' to significantly 'bend the curve' of rising health care costs:<ref>{{cite book|last=Gruber|first=Jonathan|title=Health Care Reform: What It Is, Why It's Necessary, How It Works|year=2011|publisher=Hill and Wang|location=United States|isbn=978-0-8090-5397-1|page=101}}</ref>{{cquote|The real question is how far the ACA will go in slowing cost growth. Here, there is great uncertainty—mostly because there is such uncertainty in general about how to control cost growth in health care. There is no shortage of good ideas for ways of doing so... There is, however, a shortage of evidence regarding which approaches will actually work—and therefore no consensus on which path is best to follow. In the face of such uncertainty, the ACA pursued the path of considering a range of different approaches to controlling health care costs... Whether these policies by themselves can fully solve the long run health care cost problem in the United States is doubtful. They may, however, provide a first step towards controlling costs—and understanding what does and does not work to do so more broadly.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://economics.mit.edu/files/6829 |last=Gruber|first=Jonathan|title=The Impacts Of The Affordable Care Act: How Reasonable Are The Projections?}}</ref>}} | ||

Revision as of 17:05, 26 July 2013

| |

| Long title | The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act |

|---|---|

| Acronyms (colloquial) | PPACA |

| Nicknames | Affordable Care Act, Health Insurance Reform, Healthcare Reform, Obamacare |

| Enacted by | the 111th United States Congress |

| Effective | March 23, 2010 Most major provisions phased in by January 2014; remaining provisions phased in by 2020 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | 111–148 |

| Statutes at Large | 124 Stat. 119 through 124 Stat. 1025 (906 pages) |

| Legislative history | |

| |

| Major amendments | |

| Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 Comprehensive 1099 Taxpayer Protection and Repayment of Exchange Subsidy Overpayments Act of 2011 | |

| United States Supreme Court cases | |

| National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius | |

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), commonly called Obamacare or the Affordable Care Act (ACA), is a United States federal statute signed into law by President Barack Obama on March 23, 2010. Together with the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act, it represents the most significant government expansion and regulatory overhaul of the U.S. healthcare system since the passage of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965.

The ACA is aimed at increasing the affordability and rate of health insurance coverage for Americans, and reducing the overall costs of health care (for individuals and the government). It provides a number of mechanisms — including mandates, subsidies, and tax credits — to employers and individuals to increase the coverage rate and health insurance affordability. The ACA requires insurance companies to cover all applicants within new minimum standards, and offer the same rates regardless of pre-existing conditions or sex. Additional reforms aim to improve healthcare outcomes and streamline the delivery of health care. The Congressional Budget Office projected that the ACA will lower both future deficits and Medicare spending.

On June 28, 2012, the United States Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of most of the ACA in the case National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius.

Overview

Provisions

The ACA includes numerous provisions to take effect over several years beginning in 2010. There is a grandfather clause on policies issued before then that exempt them from many of these provisions, but other provisions may affect existing policies.

- Guaranteed issue will require policies to be issued regardless of any medical condition, and partial community rating will require insurers to offer the same premium to all applicants of the same age and geographical location without regard to gender or most pre-existing conditions (excluding tobacco use).

- A shared responsibility requirement, commonly called an individual mandate, requires all individuals not covered by an employer sponsored health plan, Medicaid, Medicare or other public insurance programs, to secure an approved private-insurance policy or pay a penalty, unless the applicable individual is a member of a recognized religious sect exempted by the Internal Revenue Service, or waived in cases of financial hardship. This was included on the rationale that - without such a mandate, a form of community rating, and coverage standards - the guaranteed issue provision would likely exacerbate adverse selection: if people could not be denied insurance by companies they might put-off insuring themselves until they got sick, causing insurers to resort to larger premium increases on sick individuals and more extensive coverage limits to afford the remaining insured population, which could result in an insurance death spiral. This led to the inclusion of subsidies (see below) so people with low-incomes can comply when the mandate goes into effect.

- Health insurance exchanges will commence operation in each state, offering a marketplace where individuals and small businesses can compare policies and premiums, and buy insurance (with a government subsidy if eligible).

- Low-income individuals and families above 100% and up to 400% of the federal poverty level will receive federal subsidies on a sliding scale if they choose to purchase insurance via an exchange (those from 133% to 150% of the poverty level would be subsidized such that their premium cost would be 3% to 4% of income).

- The text of the law expands Medicaid eligibility to include all individuals and families with incomes up to 133% of the poverty level, and simplifies the CHIP enrollment process. In National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, the Supreme Court effectively allowed states to opt out of the Medicaid expansion, and some states have stated their intention to do so. States that choose to reject the Medicaid expansion can set their own Medicaid eligibility thresholds, which in many states are significantly below 133% of the poverty line; in addition, many states do not make Medicaid available to childless adults at any income level. Because subsidies on insurance plans purchased through exchanges are not available to those below 100% of the poverty line, this may create a coverage gap in those states.

- Minimum standards for health insurance policies are to be established (an 'essential health benefits'), and annual and lifetime coverage caps will be banned.

- Firms employing 50 or more people but not offering health insurance will also pay a shared responsibility requirement if the government has had to subsidize an employee's health care.

- Very small businesses will be able to get subsidies if they purchase insurance through an exchange.

- Co-payments, co-insurance, and deductibles are to be eliminated for select health care insurance benefits considered to be part of the "essential benefits package" for Level A or Level B preventive care.

- Changes are enacted that allow a restructuring of Medicare reimbursement from "fee-for-service" to "bundled payment." A single payment is paid to a hospital and a physician group, for example, for a defined episode of care (such as a hip replacement), rather than individual payments to individual service-providers.

Funding

The ACA's provisions are funded by a variety of taxes and offsets. Major sources of new revenue include a much-broadened Medicare tax on incomes over $200,000 and $250,000, for individual and joint filers respectively, an annual fee on insurance providers, and a 40% excise tax on "Cadillac" insurance policies. The income levels are not adjusted for inflation, leaving the possibility of increased taxes on incomes over 250,000 inflation-adjusted dollars after more than two decades without indexing through. There are also taxes on pharmaceuticals, high-cost diagnostic equipment, and a 10% federal sales tax on indoor tanning services. Offsets are from intended cost savings such as changes in the Medicare Advantage program relative to traditional Medicare.

Summary of tax increases: (ten-year projection)

- Increase Medicare tax rate by .9% and impose added tax of 3.8% on unearned income for high-income taxpayers: $210.2 billion

- Charge an annual fee on health insurance providers: $60 billion

- Impose a 40% excise tax on health insurance annual premiums in excess of $10,200 for an individual or $27,500 for a family: $32 billion

- Impose an annual fee on manufacturers and importers of branded drugs: $27 billion

- Impose a 2.3% excise tax on manufacturers and importers of certain medical devices:$20 billion

- Raise the 7.5% Adjusted Gross Income floor on medical expenses deduction to 10%: $15.2 billion

- Limit annual contributions to flexible spending arrangements in cafeteria plans to $2,500: $13 billion

- All other revenue sources: $14.9 billion

Summary of spending offsets: (ten year projection)

- Reduce funding for Medicare Advantage policies: $132 billion

- Reduce Medicare home health care payments: $40 billion

- Reduce certain Medicare hospital payments: $22 billion

Original budget estimates included a provision to require information reporting on payments to corporations, which had been projected to raise $17 billion, but the provision was repealed.

Provisions by effective date

The ACA is divided into 10 titles and contains provisions that became effective immediately, 90 days after enactment, and six months after enactment, as well as provisions phased in through to 2020. Below are some of the key provisions of the ACA. For simplicity, the amendments in the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 are integrated into this timeline.

Effective at enactment

- The Food and Drug Administration is now authorized to approve generic versions of biologic drugs and grant biologics manufacturers 12 years of exclusive use before generics can be developed.

- The Medicaid drug rebate (paid by drug manufacturers to the states) for brand name drugs is increased to 23.1% (except the rebate for clotting factors and drugs approved exclusively for pediatric use increases to 17.1%), and the rebate is extended to Medicaid managed care plans; the Medicaid rebate for non-innovator, multiple source drugs is increased to 13% of average manufacturer price.

- A non-profit Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute is established, independent from government, to undertake comparative effectiveness research. This is charged with examining the "relative health outcomes, clinical effectiveness, and appropriateness" of different medical treatments by evaluating existing studies and conducting its own. Its 19-member board is to include patients, doctors, hospitals, drug makers, device manufacturers, insurers, payers, government officials and health experts. It will not have the power to mandate or even endorse coverage rules or reimbursement for any particular treatment. Medicare may take the Institute's research into account when deciding what procedures it will cover, so long as the new research is not the sole justification and the agency allows for public input. The bill prohibits the Institute from developing or employing "a dollars per quality adjusted life year" (or similar measure that discounts the value of a life because of an individual's disability) as a threshold to establish what type of health care is cost effective or recommended. This makes it different from the UK's National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, which determines cost-effectiveness directly based on quality-adjusted life year valuations.

- Creation of task forces on Preventive Services and Community Preventive Services to develop, update, and disseminate evidenced-based recommendations on the use of clinical and community prevention services.

- The Indian Health Care Improvement Act is reauthorized and amended.

- Chain restaurants and food vendors with 20 or more locations are required to display the caloric content of their foods on menus, drive-through menus, and vending machines. Additional information, such as saturated fat, carbohydrate, and sodium content, must also be made available upon request. But first, the Food and Drug Administration has to come up with regulations, and as a result, calories disclosures may not appear until 2013 or 2014.

- States can apply for a 'State Plan Amendment" to expand family planning eligibility to the same eligibility as pregnancy related care (above and beyond Medicaid level eligibility), through a state option rather than having to apply for a federal waiver.

Effective June 21, 2010

- Adults with existing conditions became eligible to join a temporary high-risk pool, which will be superseded by the health care exchange in 2014. To qualify for coverage, applicants must have a pre-existing health condition and have been uninsured for at least the past six months. There is no age requirement. The new program sets premiums as if for a standard population and not for a population with a higher health risk. Allows premiums to vary by age (3:1), geographic area, family composition and tobacco use (1.5:1). Limit out-of-pocket spending to $5,950 for individuals and $11,900 for families, excluding premiums.

Effective July 1, 2010

- The President established, within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), a council to be known as the National Prevention, Health Promotion and Public Health Council to help begin to develop a National Prevention and Health Promotion Strategy. The Surgeon General shall serve as the Chairperson of the new Council.

- A 10% sales tax on indoor tanning took effect.

Effective September 23, 2010

- Insurers are prohibited from imposing lifetime dollar limits on essential benefits, like hospital stays, in new policies issued.

- Dependents (children) will be permitted to remain on their parents' insurance plan until their 26th birthday, and regulations implemented under the ACA include dependents that no longer live with their parents, are not a dependent on a parent's tax return, are no longer a student, or are married.

- Insurers are prohibited from excluding pre-existing medical conditions (except in grandfathered individual health insurance plans) for children under the age of 19.

- All new insurance plans must cover preventive care and medical screenings rated Level A or B by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Insurers are prohibited from charging co-payments, co-insurance, or deductibles for these services.

- Individuals affected by the Medicare Part D coverage gap will receive a $250 rebate, and 50% of the gap will be eliminated in 2011. The gap will be eliminated by 2020.

- Insurers' abilities to enforce annual spending caps will be restricted, and completely prohibited by 2014.

- Insurers are prohibited from dropping policyholders when they get sick.

- Insurers are required to reveal details about administrative and executive expenditures.

- Insurers are required to implement an appeals process for coverage determination and claims on all new plans.

- Enhanced methods of fraud detection are implemented.

- Medicare is expanded to small, rural hospitals and facilities.

- Medicare patients with chronic illnesses must be monitored/evaluated on a 3-month basis for coverage of the medications for treatment of such illnesses.

- Companies which provide early retiree benefits for individuals aged 55–64 are eligible to participate in a temporary program which reduces premium costs.

- A new website installed by the Secretary of Health and Human Services will provide consumer insurance information for individuals and small businesses in all states.

- A temporary credit program is established to encourage private investment in new therapies for disease treatment and prevention.

- All new insurance plans must cover childhood immunizations and adult vaccinations recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) without charging co-payments, co-insurance, or deductibles when provided by an in-network provider.

Effective January 1, 2011

- Insurers must spend 80% (for individual or small group insurers) or 85% (for large group insurers) of premium dollars on health costs and claims, leaving only 20% or 15% respectively for administrative costs and profits, subject to various waivers and exemptions. If an insurer fails to meet this requirement, there is no penalty, but a rebate must be issued to the policy holder. This policy is known as the 'Medical Loss Ratio'.

- The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is responsible for developing the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation and overseeing the testing of innovative payment and delivery models.

- Flexible spending accounts, Health reimbursement accounts and health savings accounts cannot be used to pay for over-the-counter drugs, purchased without a prescription, except insulin.

Effective September 1, 2011

- All health insurance companies must inform the public when they want to increase health insurance rates for individual or small group policies by an average of 10% or more. This policy is known as 'Rate Review'. States are provided with Health Insurance Rate Review Grants to enhance their rate review programs and bring greater transparency to the process.

Effective January 1, 2012

- Employers must disclose the value of the benefits they provided beginning in 2012 for each employee's health insurance coverage on the employee's annual Form W-2's. This requirement was originally to be effective January 1, 2011, but was postponed by IRS Notice 2010–69 on October 23, 2010. Reporting is not required for any employer that was required to file fewer than 250 Forms W-2 in the preceding calendar year.

- New tax reporting changes were to come in effect. Lawmakers originally felt these changes would help prevent tax evasion by corporations. However, in April 2011, Congress passed and President Obama signed the Comprehensive 1099 Taxpayer Protection and Repayment of Exchange Subsidy Overpayments Act of 2011 repealing this provision, because it was burdensome to small businesses. Before the ACA, businesses were required to notify the IRS on form 1099 of certain payments to individuals for certain services or property over a reporting threshold of $600. Under the repealed law, reporting of payments to corporations would also be required. Originally it was expected to raise $17 billion over 10 years. The amendments made by Section 9006 of the ACA were designed to apply to payments made by businesses after December 31, 2011, but will no longer apply because of the repeal of the section.

Effective August 1, 2012

- All new plans must cover certain preventive services such as mammograms and colonoscopies without charging a deductible, co-pay or coinsurance. Women's Preventive Services – including: well-woman visits; gestational diabetes screening; human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA testing for women age 30 and older; sexually transmitted infection counseling; human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) screening and counseling; FDA-approved contraceptive methods and contraceptive counseling; breastfeeding support, supplies and counseling; and domestic violence screening and counseling - will be covered without cost sharing. This is also known as the contraceptive mandate.

Effective October 1, 2012

- The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) will begin the Readmissions Reduction Program, which requires CMS to reduce payments to IPPS hospitals with excess readmissions, effective for discharges beginning on October 1, 2012. The regulations that implement this provision are in subpart I of 42 CFR part 412 (§412.150 through §412.154). Starting in October, an estimated total of 2,217 hospitals across the nation will be penalized; however, only 307 of these hospitals will receive this year's maximum penalty, i.e., 1 percent off their base Medicare reimbursements. The penalty will be deducted from reimbursements each time a hospital submits a claim starting Oct. 1. The maximum penalty will increase after this year, to 2 percent of regular payments starting in October 2013 and then to 3 percent the following year. As an example, if a hospital received the maximum penalty of 1 percent and it submitted a claim for $20,000 for a stay, Medicare would reimburse it $19,800. Together, these 2,217 hospitals will forfeit more than $280 million in Medicare funds over the next year, i.e., until October 2013, as Medicare and Medicaid begin a wide-ranging push to start paying health care providers based on the quality of care they provide. The $280 million in penalties comprises about 0.3 percent of the total amount hospitals are paid by Medicare.

Effective January 1, 2013

- Income from self-employment and wages of single individuals in excess of $200,000 annually will be subject to an additional tax of 0.9%. The threshold amount is $250,000 for a married couple filing jointly (threshold applies to joint compensation of the two spouses), or $125,000 for a married person filing separately. In addition, an additional Medicare tax of 3.8% will apply to unearned income, specifically the lesser of net investment income or the amount by which adjusted gross income exceeds $200,000 ($250,000 for a married couple filing jointly; $125,000 for a married person filing separately.)

- Beginning January 1, 2013, the limit on pre-tax contributions to healthcare flexible spending accounts will be capped at $2,500 per year.

- Most medical devices become subject to a 2.3% excise tax collected at the time of purchase. (Reduced by the reconciliation act from 2.6% to 2.3%.) This tax will also apply to some medical devices, such as examination gloves and catheters, that are used in veterinary medicine.

- Insurance companies are required to use simpler, more standardized paperwork, with the intention of helping consumers make apples-to-apples comparisons between the prices and benefits of different health plans.

Effective by August 1, 2013

- Religious organizations that were given an extra year to implement the contraceptive mandate are no longer exempt. Certain non-exempt, non-grandfathered group health plans established and maintained by non-profit organizations with religious objections to covering contraceptive services may take advantage of a one-year enforcement safe harbor (i.e., until the first plan year beginning on or after August 1, 2013) by timely satisfying certain requirements set forth by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

Effective by October 1, 2013

- Individuals can enroll in subsidized health insurance plans offered through state-based health insurance exchanges. Coverage begins on January 1, 2014.

Effective by January 1, 2014

- Insurers are prohibited from discriminating against or charging higher rates for any individual based on pre-existing medical conditions or gender.

- Insurers are prohibited from establishing annual spending caps.

- Under the mandatory coverage provision, individuals who are not covered by an acceptable insurance policy will be charged an annual penalty of $95, or up to 1% of income over the filing minimum, whichever is greater; this will rise to a minimum of $695 ($2,085 for families), or 2.5% of income over the filing minimum, by 2016. Exemptions are permitted for religious reasons, members of health care sharing ministries, or for those for whom the least expensive policy would exceed 8% of their income. In 2010, the Commissioner speculated that insurance providers would supply a form confirming essential coverage to both individuals and the IRS; individuals would attach this form to their Federal tax return. Those who aren't covered will be assessed the penalty on their Federal tax return. In the wording of the law, a taxpayer who fails to pay the penalty "shall not be subject to any criminal prosecution or penalty", and cannot have liens or levies placed on their property, but the IRS will be able to withhold future tax refunds from them.

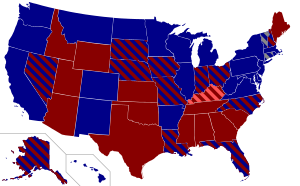

- In participating states, Medicaid eligibility is expanded; all individuals with income up to 133% of the poverty line qualify for coverage, including adults without dependent children. The law also provides for a 5% "income disregard", making the effective income eligibility limit 138% of the poverty line. Participating states may choose to increase the income eligibility limit beyond this minimum requirement. As written, the ACA withheld all Medicaid funding from states declining to participate in the expansion. However, the Supreme Court ruled in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2012) that this withdrawal of funding was unconstitutionally coercive and that individual states had the right to opt out of the Medicaid expansion without losing pre-existing Medicaid funding from the federal government. As of April 25, 2013, fifteen states—Alaska, Alabama, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Mississippi, Nebraska, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas, Wisconsin, and Virginia—were not participating in the Medicaid expansion, with ten more—Kansas, Maine, Michigan, Montana, Missouri, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming—leaning towards not participating.

- Health insurance exchanges are established, and subsides for insurance premiums are given to individuals who buy a plan from an exchange and have a household income between 133% and 400% of the poverty line. Section 1401(36B) of PPACA explains that each subsidy will be provided as an advanceable, refundable tax credit and gives a formula for its calculation. A refundable tax credit is a way to provide government benefits to individuals who may have no tax liability (such as the Earned Income Tax Credit). The formula was changed in the amendments (HR 4872) passed March 23, 2010, in section 1001. To qualify for the subsidy, the beneficiaries cannot be eligible for other acceptable coverage. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and Internal Revenue Service (IRS) on May 23, 2012, issued joint final rules regarding implementation of the new state-based health insurance exchanges to cover how the exchanges will determine eligibility for uninsured individuals and employees of small businesses seeking to buy insurance on the exchanges, as well as how the exchanges will handle eligibility determinations for low-income individuals applying for newly expanded Medicaid benefits. According to DHHS and CRS, in 2014 the income-based premium caps for a "silver" healthcare plan for a family of four will be the following:

| Income % of federal poverty level | Premium Cap as a Share of Income | Income $ (family of 4) | Max Annual Out-of-Pocket Premium | Premium Savings | Additional Cost-Sharing Subsidy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 133% | 3% of income | $31,900 | $992 | $10,345 | $5,040 |

| 150% | 4% of income | $33,075 | $1,323 | $9,918 | $5,040 |

| 200% | 6.3% of income | $44,100 | $2,778 | $8,366 | $4,000 |

| 250% | 8.05% of income | $55,125 | $4,438 | $6,597 | $1,930 |

| 300% | 9.5% of income | $66,150 | $6,284 | $4,628 | $1,480 |

| 350% | 9.5% of income | $77,175 | $7,332 | $3,512 | $1,480 |

| 400% | 9.5% of income | $88,200 | $8,379 | $2,395 | $1,480 |

|

a. Note: In 2016, the FPL is projected to equal about $11,800 for a single person and about $24,000 for family of four. See Subsidy Calculator for specific dollar amount. b. DHHS and CBO estimate the average annual premium cost in 2014 to be $11,328 for family of 4 without the reform. | |||||

- Two federally regulated 'multi-state plan' (MSP) insurers, with one being non-profit and the other being forbidden from providing coverage for abortion services, become partially available. They will have to abide by the same federal regulations as required by individual state's qualified health plans available on the exchanges and must provide the same identical cover privileges and premiums in all states. MSPs will be phased in nationally, being available in 60% of all states in 2014, 70% in 2015, 85% in 2016 with full national coverage in 2017.

- Section 2708 to the Public Health Service Act becomes effective, which prohibits patient eligibility waiting periods in excess of 90 days for group health plan coverage. The 90-day rule applies to all grandfathered and non-grandfathered group health plans and group health insurance issuers, including multiemployer health plans and single-employer group health plans pursuant to collective bargaining arrangements. Plans will still be allowed to impose eligibility requirements based on factors other than the lapse of time; for example, a health plan can restrict eligibility to employees who work at a particular location or who are in an eligible job classification. The waiting period limitation means that coverage must be effective no later than the 91st day after the employee satisfies the substantive eligibility requirements.

- Two years of tax credits will be offered to qualified small businesses. To receive the full benefit of a 50% premium subsidy, the small business must have an average payroll per full-time equivalent ("FTE") employee of no more than $50,000 and have no more than 25 FTEs. For the purposes of the calculation of FTEs, seasonal employees, and owners and their relations, are not considered. The subsidy is reduced by 3.35 percentage points per additional employee and 2 percentage points per additional $1,000 of average compensation. As an example, a 16 FTE firm with a $35,000 average salary would be entitled to a 10% premium subsidy.

- A $2,000 per employee penalty will be imposed on employers with more than 50 full-time employees who do not offer health insurance to their full-time workers (as amended by the reconciliation bill). "Full-time" is defined as, with respect to any month, an employee who is employed on average at least 30 hours of service per week. In July 2013, the Obama administration announced this penalty would not be enforced until January 1, 2015.

- For employer-sponsored plans, a $2,000 maximum annual deductible is established for any plan covering a single individual or a $4,000 maximum annual deductible for any other plan (see 111HR3590ENR, section 1302). These limits can be increased under rules set in section 1302.

- To finance part of the new spending, spending and coverage cuts are made to Medicare Advantage, the growth of Medicare provider payments are slowed (in part through the creation of a new Independent Payment Advisory Board), Medicare and Medicaid drug reimbursement rates are decreased, and other Medicare and Medicaid spending is cut.

- Revenue is increased from a new $2,500 limit on tax-free contributions to flexible spending accounts (FSAs), which allow for payment of health costs.

- Members of Congress and their staff are only offered health care plans through the exchanges or plans otherwise established by the bill (instead of the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program that they currently use).

- A new excise tax goes into effect that is applicable to pharmaceutical companies and is based on the market share of the company; it is expected to create $2.5 billion in annual revenue.

- Health insurance companies become subject to a new excise tax based on their market share; the rate gradually rises between 2014 and 2018 and thereafter increases at the rate of inflation. The tax is expected to yield up to $14.3 billion in annual revenue.

- The qualifying medical expenses deduction for Schedule A tax filings increases from 7.5% to 10% of adjusted gross income (AGI).

- Consumer Operated and Oriented Plans (CO-OP), which are member-governed non-profit insurers, entitled to a 5-year federal loan, are permitted to start providing health care coverage.

- The CLASS Act provision would have created a voluntary long-term care insurance program, but in October 2011 the Department of Health and Human Services announced that the provision was unworkable and would be dropped. The CLASS Act was repealed January 1, 2013.

Effective by October 1, 2014

- Federal payments to so-called 'disproportionate share hospitals', which treat large numbers of indigent patients, are to be reduced and subsequently allowed to rise based on the percentage of the population that is uninsured in each state.

Effective by January 1, 2015

- CMS begins using the Medicare fee schedule to give larger payments to physicians who provide high-quality care compared with cost.

Effective by October 1, 2015

- States are allowed to shift children eligible for care under the Children's Health Insurance Program to health care plans sold on their exchanges, as long as HHS approves.

Effective by January 1, 2016

- States are permitted to form health care choice compacts and allows insurers to sell policies in any state participating in the compact.

- The threshold for itemizing medical expenses increases from 7.5% of income to 10% for seniors.

Effective by January 1, 2017

- A state may apply to the Secretary of Health & Human Services for a "waiver for state innovation" provided that the state passes legislation implementing an alternative health care plan meeting certain criteria. The decision of whether to grant the waiver is up to the Secretary (who must annually report to Congress on the waiver process) after a public comment period. A state receiving the waiver would be exempt from some of the central requirements of the ACA, including the individual mandate, the creation by the state of an insurance exchange, and the penalty for certain employers not providing coverage. The state would also receive compensation equal to the aggregate amount of any federal subsidies and tax credits for which its residents and employers would have been eligible under the ACA plan, but which cannot be paid out due to the structure of the state plan. To qualify for the waiver, the state plan must provide insurance at least as comprehensive and as affordable as that required by the ACA, must cover at least as many residents as the ACA plan would, and cannot increase the federal deficit. The coverage must continue to meet the consumer protection requirements of the ACA, such as the prohibition on increasing premiums because of pre-existing conditions. A bipartisan bill sponsored by Senators Ron Wyden and Scott Brown, and supported by President Obama, proposes making waivers available in 2014 rather than 2017, so that, for example, states that wish to implement an alternative plan need not set up an insurance exchange only to dismantle it a short time later. In April 2011 Vermont announced its intention to pursue a waiver to implement the single-payer system enacted in May 2011. In September 2011 Montana announced it would also be seeking a waiver to set up its own single payer healthcare system.

- States may allow large employers and multi-employer health plans to purchase coverage in the Exchange.

- Two federally regulated 'multi-state plan' (MSP) insurers are scheduled to be fully phased-in, becoming available to all states (for more, see: section on provisions effective by January 1, 2014).

Effective by January 1, 2018

- All existing health insurance plans must cover approved preventive care and checkups without co-payment.

- A 40% excise tax on high cost ("Cadillac") insurance plans is introduced. The tax (as amended by the reconciliation bill) is on insurance premiums in excess of $27,500 (family plans) and $10,200 (individual plans), and it is increased to $30,950 (family) and $11,850 (individual) for retirees and employees in high risk professions. The dollar thresholds are indexed with inflation; employers with higher costs on account of the age or gender demographics of their employees may value their coverage using the age and gender demographics of a national risk pool.

Effective by January 1, 2019

- Medicaid extends coverage to former foster care youths who were in foster care for at least six months and are under 25 years old.

Effective by January 1, 2020

- The Medicare Part D coverage gap (a.k.a., "donut hole") will be completely phased out and hence closed.

Legislative history

Background

Main articles: Health care reform in the United States and Health care reform debate in the United StatesThe plan that ultimately became the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act consists of a combination of measures to control health care costs and an insurance expansion through public insurance (expanded Medicaid eligibility and Medicare coverage) and subsidized, regulated private insurance. The latter of these ideas forms the core of the law's insurance expansion, and it has been included in bipartisan reform proposals in the past. In particular, the idea of an individual mandate coupled with subsidies for private insurance, as an alternative to public insurance, was considered a way to get Universal Health Insurance that could win the support of the Senate. Many healthcare policy experts have pointed out that the individual mandate requirement to buy health insurance was contained in many previous proposals by Republicans for healthcare legislation, going back as far as 1989, when it was initially proposed by the politically conservative Heritage Foundation as an alternative to single-payer health care. The idea of an individual mandate was championed by Republican politicians as a market-based approach to health-care reform, on the basis of individual responsibility: because the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA), passed in 1986 by a bipartisan Congress and signed by Ronald Reagan, requires any hospital participating in Medicare (nearly all do) to provide emergency care to anyone who needs it, the government often indirectly bore the cost of those without the ability to pay.

When, in 1993, President Bill Clinton proposed a health-care reform bill which included a mandate for employers to provide health insurance to all employees through a regulated marketplace of health maintenance organizations, Republican Senators proposed a bill that would have required individuals, and not employers, to buy insurance, as an alternative to Clinton's plan. Ultimately the Clinton plan failed amid concerns that it was overly complex or unrealistic, and in the face of an unprecedented barrage of negative advertising funded by politically conservative groups and the health-insurance industry. (After failing to obtain a comprehensive reform of the health care system, Clinton did however negotiate a compromise with the 105th Congress to instead enact the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) in 1997).

The 1993 Republican alternative, introduced by Senator John Chafee (R-RI) as the Health Equity and Access Reform Today Act, contained a "Universal Coverage" requirement with a penalty for non-compliance. Advocates for the 1993 bill which contained the individual mandate included prominent Republicans who today oppose the mandate, such as Orrin Hatch (R-UT), Charles Grassley (R-IA), Bob Bennett (R-UT), and Christopher Bond (R-MO). Of the 43 Republicans Senators from 1993, almost half - 20 out of 43 - supported the HEART Act. And in 1994 Senator Don Nickles (R-OK) introduced the Consumer Choice Health Security Act which also contained an individual mandate with a penalty provision - however, subsequently, he did remove the mandate from the act after introduction stating that they had decided "that government should not compel people to buy health insurance." At the time of these proposals, Republicans did not raise constitutional issues with the mandate; Mark Pauly, who helped develop a proposal that included an individual mandate for George H.W. Bush, remarked, "I don’t remember that being raised at all. The way it was viewed by the Congressional Budget Office in 1994 was, effectively, as a tax... So I’ve been surprised by that argument."

An individual health-insurance mandate was also enacted at the state-level in Massachusetts: In 2006, Republican Mitt Romney, then governor of Massachusetts, signed an insurance expansion bill with an individual mandate into law with strong bipartisan support (including that of Ted Kennedy (D-MA)). Romney's success in installing an individual mandate in Massachusetts was at first lauded by Republicans. During Romney's 2008 Presidential campaign, Senator Jim DeMint (R-SC) praised Romney's ability to "take some good conservative ideas, like private health insurance, and apply them to the need to have everyone insured." Romney himself said of the individual mandate: "I'm proud of what we've done. If Massachusetts succeeds in implementing it, then that will be the model for the nation."

The following year (2007), Senators Bob Bennett (R-UT) and Ron Wyden (D-OR) introduced the Healthy Americans Act, a bill that also featured an individual mandate, and which attracted bipartisan support. Among the Republican co-sponsors still in Congress during the health care debate: Senators Chuck Grassley (R-IA), Lindsey Graham (R-SC), Bob Bennett (R-UT), Mike Crapo (R-ID), Bob Corker (R-TN), Lamar Alexander (R-TN), and Arlen Specter (R-PA).

Given the history of bipartisan support for the idea, and its track record in Massachusetts; by 2008 Democrats were considering it as a basis for comprehensive, national health care reform: Experts have pointed out that the legislation that eventually emerged from Congress in 2009 and 2010 bears many similarities to the 2007 bill; and that it was deliberately patterned after former Republican Governor of Massachusetts Mitt Romney's state healthcare plan (which contains an individual mandate). Jonathan Gruber, a key architect of the Massachusetts reform, advised the Clinton and Obama Presidential campaigns on their health care proposals, served as a technical consultant to the Obama Administration, and helped Congress draft the ACA.

Health care debate, 2008–2010

Main article: Health care reforms proposed during the Obama administrationHealth care reform was a major topic of discussion during the 2008 Democratic presidential primaries. As the race narrowed, attention focused on the plans presented by the two leading candidates, New York Senator Hillary Clinton and the eventual nominee, Illinois Senator Barack Obama. Each candidate proposed a plan to cover the approximately 45 million Americans estimated to be without health insurance at some point during each year. One point of difference between the plans was that Clinton's plan was to require all Americans to obtain coverage (in effect, an individual health insurance mandate), while Obama's was to provide a subsidy but not create a direct requirement. During the general election campaign between Obama and the Republican nominee, Arizona Senator John McCain, Obama said that fixing health care would be one of his top four priorities if he won the presidency.

After his inauguration, Obama announced to a joint session of Congress in February 2009 that he would begin working with Congress to construct a plan for health care reform. On March 5, 2009, Obama formally began the reform process and held a conference with industry leaders to discuss reform. By July, a series of bills were approved by committees within the House of Representatives. On the Senate side, beginning June 17, 2009, and extending through September 14, 2009, three Democratic and three Republican Senate Finance Committee Members met for a series of 31 meetings to discuss the development of a health care reform bill. Over the course of the next three months, this group, Senators Max Baucus (D-MT), Chuck Grassley (R-IA), Kent Conrad (D-ND), Olympia Snowe (R-ME), Jeff Bingaman (D-NM), and Mike Enzi (R-WY), met for more than 60 hours, and the principles that they discussed (in conjunction with the other Committees) became the foundation of the Senate's health care reform bill. The meetings were held in public and broadcast by C-SPAN and can be seen on the C-SPAN web site or at the Committee's own web site.

With universal health insurance as one of the stated goals of the Obama Administration, Congressional Democrats and health policy experts like Jonathan Gruber and David Cutler argued that guaranteed issue would require both a (partial) community rating and an individual health insurance mandate to prevent either adverse selection and/or free riding from creating an insurance death spiral. They convinced Obama that this was necessary, which persuaded the Administration to accept Congressional proposals that included a mandate. This approach was preferred because the President and Congressional leaders concluded that more liberal plans (such as Medicare-for-all) could not win filibuster-proof support in the Senate. By deliberately drawing on bipartisan ideas - the same basic outline was supported by former Senate Majority Leaders Howard Baker (R-TN), Bob Dole (R-KS), Tom Daschle (D-SD) and George Mitchell (D-ME) - the bill's drafters hoped to increase the chances of getting the necessary votes for passage.

However, following the adoption of an individual mandate as a central component of the proposed reforms by Democrats, Republicans began to oppose the mandate and threaten to filibuster any bills that contained it. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY), who lead the Republican Congressional strategy in responding to the bill, calculated that Republicans should not support the bill, and worked to keep party discipline and prevent defections:

It was absolutely critical that everybody be together because if the proponents of the bill were able to say it was bipartisan, it tended to convey to the public that this is O.K., they must have figured it out.

Republican Senators (including those who had supported previous bills with a similar mandate) began to describe the mandate as "unconstitutional". Writing in The New Yorker, Ezra Klein stated that "the end result was... a policy that once enjoyed broad support within the Republican Party suddenly faced unified opposition." The New York Times subsequently noted: "It can be difficult to remember now, given the ferocity with which many Republicans assail it as an attack on freedom, but the provision in President Obama's health care law requiring all Americans to buy health insurance has its roots in conservative thinking."

The reform negotiations also attracted a great deal of attention from lobbyists, including deals among certain lobbies and the advocates of the law to win the support of groups who had opposed past reform efforts, such as in 1993. The Sunlight Foundation documented many of the reported ties between "the healthcare lobbyist complex" and politicians in both major parties.

During the August 2009 summer congressional recess, many members went back to their districts and entertained town hall meetings to solicit public opinion on the proposals. Over the recess, the Tea Party movement organized protests and many conservative groups and individuals targeted congressional town hall meetings to voice their opposition to the proposed reform bills. There were also many threats made against members of Congress over the course of the Congressional debate, and many were assigned extra protection.

To maintain the progress of the legislative process, when Congress returned from recess, in September 2009 President Obama delivered a speech to a joint session of Congress supporting the ongoing Congressional negotiations, to re-emphasize his commitment to reform and again outline his proposals. In it he acknowledged the polarization of the debate, and quoted a letter from the late-Senator Ted Kennedy urging on reform: "what we face is above all a moral issue; that at stake are not just the details of policy, but fundamental principles of social justice and the character of our country." On November 7, the House of Representatives passed the Affordable Health Care for America Act on a 220–215 vote and forwarded it to the Senate for passage.

Senate

The Senate began work on its own proposals while the House was still working on its bill (the Affordable Health Care for America Act); it instead took up H.R. 3590, a bill regarding housing tax breaks for service members. As the United States Constitution requires all revenue-related bills to originate in the House, the Senate took up this bill since it was first passed by the House as a revenue-related modification to the Internal Revenue Code. The bill was then used as the Senate's vehicle for their health care reform proposal, completely revising the content of the bill. The bill as amended would ultimately incorporate elements of proposals that were reported favorably by the Senate Health and Finance committees.

With the Republican minority in the Senate vowing to filibuster any bill that they did not support, requiring a cloture vote to end debate, 60 votes would be necessary to get passage in the Senate. At the start of the 111th Congress, Democrats had only 58 votes (the Senate seat in Minnesota that would be won by Al Franken was still undergoing a recount, and Arlen Specter was still a Republican). To reach 60 votes, negotiations were undertaken to satisfy the demands of moderate Democrats, and to try to bring aboard several Republican Senators (particular attention was given to Bob Bennett, Chuck Grassley, Mike Enzi, and Olympia Snowe). Negotiations continued even after July 7 – when Al Franken was sworn into office and by which time Arlen Specter had switched parties – because of disagreements over the substance of the bill, which was still being drafted in committee, and because moderate Democrats hoped to win bipartisan support. However, on August 25, before the bill could come up for a vote, Ted Kennedy – a long-time advocate for health care reform – died, depriving Democrats of their 60th vote. Whilst Paul Kirk was appointed as Senator Kennedy's temporary replacement on September 24 (regaining the Democrats' 60th vote); attention was drawn to Senator Snowe because of her vote in favor of the draft bill in the Finance Committee on October 15, however she explicitly stated that this did not mean she would support the final bill.

Following the Finance Committee vote, negotiations turned to the demands of moderate Democrats to finalize their support, whose votes would be necessary to break the Republican filibuster. Majority Leader Harry Reid focused on satisfying the centrist members of the Democratic caucus until the hold-outs narrowed down to Connecticut's Joe Lieberman (an independent who caucused with Democrats) and Nebraska's Ben Nelson. Lieberman, despite intense negotiations in search of a compromise by Reid, refused to support a public option; a concession granted only after Lieberman agreed to commit to voting for the bill if the provision was not included, even though it had majority support in Congress. There was debate among supporters of the bill about the importance of the public option, although the vast majority of supporters concluded that the it was a minor part of the reform overall, and that Congressional Democrats' fight for it won various concessions (including conditional waivers allowing states to set up state-based public options, for example Vermont's Green Mountain Care).

With every other Democrat now in favor and every other Republican now overtly opposed, the White House and Reid moved on to addressing Senator Nelson's concerns in order to win filibuster-proof support for the bill; they had by this point concluded that "it was a waste of time dealing with " because, after her vote for the draft bill in the Finance Committee, Snowe had come under intense pressure from the Republican Senate Leadership who opposed reform. (Snowe retired at the end of her term, citing partisanship and polarization). After a final 13-hour negotiation, Nelson's support for the bill was won after two concessions: a compromise on abortion, modifying the language of the bill "to give states the right to prohibit coverage of abortion within their own insurance exchanges" (requiring consumers to pay for the procedure out-of-pocket, if the state decided it); and an amendment to offer a higher rate of Medicaid reimbursement for Nebraska. The latter half of the compromise was derisively referred to as the "Cornhusker Kickback" (and was later repealed by the subsequent reconciliation amendment bill).