| Revision as of 18:01, 7 November 2013 edit2620:0:862:1:91:198:174:67 (talk) →Published works← Previous edit | Revision as of 18:02, 7 November 2013 edit undoK6ka (talk | contribs)Administrators115,037 editsm Reverted 3 edits by 2620:0:862:1:91:198:174:67 (talk) to last revision by 128.227.196.146. (TW)Next edit → | ||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| During the reign of ], ] launched the comic journal, ''La Caricature'', Daumier joined its staff, which included such powerful artists as ], ] and ], and started upon his pictorial campaign of satire, targeting the foibles of the ], the corruption of the law and the incompetence of a blundering ]. His caricature of the king as '']'' led to Daumier's imprisonment for six months at Ste Pelagie in 1832. Soon after, the publication of ''La Caricature'' was discontinued, but Philipon provided a new field for Daumier's activity when he founded the '']''. | |||

| Shoe | |||

| Daumier produced his social caricatures for ''Le Charivari'', in which he held bourgeois society up to ridicule in the figure of Robert Macaire, hero of a popular ]. In another series, ''L'histoire ancienne'', he took aim at the constraining pseudo-classicism of the art of the period. In 1848 Daumier embarked again on his political campaign, still in the service of ''Le Charivari'', which he left in 1863 and rejoined in 1864. | |||

| Shoe | |||

| Around the mid-1840s Daumier started publishing his famous caricatures depicting members of the legal profession, known as | |||

| Shoe | |||

| 'Les Gens de Justice', a scathing satire about judges, defendants, attorneys and corrupt, greedy lawyers in general. A number of extremely rare albums appeared on white paper, covering 39 different legal themes, of which 37 had previously been published in the Charivari. It is said that Daumier's own experience as an employee in a bailiff's office during his youth may have influenced his rather negative attitude towards the legal profession. | |||

| ==Sculptures== | ==Sculptures== | ||

Revision as of 18:02, 7 November 2013

| Honoré Daumier | |

|---|---|

Honoré Daumier circa 1850. Honoré Daumier circa 1850. | |

| Born | Honoré Victorin Daumier (1808-02-26)February 26, 1808 Marseille |

| Died | February 10, 1879(1879-02-10) (aged 70) Valmondois |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Printmaking, Painting, Sculpture |

Honoré Daumier (French: [ɔnɔʁe domje]; February 26, 1808 – February 10, 1879) was a French printmaker, caricaturist, painter, and sculptor, whose many works offer commentary on social and political life in France in the 19th century.

A prolific draftsman who produced over 500 paintings, 4000 lithographs, 1000 wood engravings, 1000 drawings, 100 sculptures he was perhaps best known for his caricatures of political figures and satires on the behavior of his countrymen, although posthumously the value of his painting has also been recognized.

Life

Daumier was born in Marseille to Jean-Baptiste Louis Daumier and Cécile Catherine Philippe. His father Jean-Baptiste was a glazier whose literary aspirations led him to move to Paris in 1814, seeking to be published as a poet. In 1816 the young Daumier and his mother followed Jean-Baptiste to Paris. Daumier showed in his youth an irresistible inclination towards the artistic profession, which his father vainly tried to check by placing him first with a huissier, for whom he was employed as an errand boy, and later, with a bookseller. In 1822 he became protégé to Alexandre Lenoir, a friend of Daumier's father who was an artist and archaeologist. The following year Daumier entered the Académie Suisse. He also worked for a lithographer and publisher named Belliard, and made his first attempts at lithography.

Having mastered the techniques of lithography, Daumier began his artistic career by producing plates for music publishers, and illustrations for advertisements. This was followed by anonymous work for publishers, in which he emulated the style of Charlet and displayed considerable enthusiasm for the Napoleonic legend. Daumier was almost blind by 1873.

Published works

During the reign of Louis Philippe, Charles Philipon launched the comic journal, La Caricature, Daumier joined its staff, which included such powerful artists as Devéria, Raffet and Grandville, and started upon his pictorial campaign of satire, targeting the foibles of the bourgeoisie, the corruption of the law and the incompetence of a blundering government. His caricature of the king as Gargantua led to Daumier's imprisonment for six months at Ste Pelagie in 1832. Soon after, the publication of La Caricature was discontinued, but Philipon provided a new field for Daumier's activity when he founded the Le Charivari.

Daumier produced his social caricatures for Le Charivari, in which he held bourgeois society up to ridicule in the figure of Robert Macaire, hero of a popular melodrama. In another series, L'histoire ancienne, he took aim at the constraining pseudo-classicism of the art of the period. In 1848 Daumier embarked again on his political campaign, still in the service of Le Charivari, which he left in 1863 and rejoined in 1864.

Around the mid-1840s Daumier started publishing his famous caricatures depicting members of the legal profession, known as 'Les Gens de Justice', a scathing satire about judges, defendants, attorneys and corrupt, greedy lawyers in general. A number of extremely rare albums appeared on white paper, covering 39 different legal themes, of which 37 had previously been published in the Charivari. It is said that Daumier's own experience as an employee in a bailiff's office during his youth may have influenced his rather negative attitude towards the legal profession.

Sculptures

Daumier was not only a prolific lithographer, draftsman and painter, but he also produced a notable number of sculptures in unbaked clay. In order to save these rare specimen from destruction, some of these busts were reproduced first in plaster. Bronze sculptures were posthumously produced from the plaster. The major 20th century foundries were F. Barbedienne Barbedienne, fr [Rudier], fr [Siot-Decauville] and fr [Foundry Valsuani].

Eventually Daumier produced between 36 busts of French members of Parliament in unbaked clay. The foundries involved from 1927 on to produce a bronze edition were Barbedienne in an edition of 25 & 30 casts and Valsuani with three special casts based on the previous plaster castings from the Sagot-Le Garrec clay collection. These bronze busts are all posthumous, based on the original, but frequently restored unbaked clay sculptures. The clay in its restored version can be seen at the Musée d'Orsay in Paris.

From the early 1950s on, some baked clay 'Figurines' appeared, most of them belonging to the Gobin collection in Paris. It was Gobin who decided to have a bronze cast done by Valsuani in an edition of 30 each. Again, they were posthumous and there is no proof, in contrast to the busts mentioned above, that these terra cotta figurines really were done by Daumier himself. The American school (J.Wasserman from the Fogg-Harvard Museum) doubts their authenticity, while the French school, especially Gobin, Lecomte and of course Le Garrec and Cherpin, all somehow involved in the marketing of the bronze editions, are sure of their Daumier origin. The Daumier Register (the international center of Daumier research) as well as the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC would consider the figurines as 'in the manner of Daumier' or even 'by an imitator of Daumier' (NGA)

There can be no doubt about the authenticity of Daumier's Ratapoil and his Emigrants. The self-portrait in bronze as well as the amazing bust of Louis XIV have been frequently debated over the last 100 years, but the general tenor is to accept them as originals by Daumier.

Paintings

In addition to his prodigious activity in the field of caricature — the list of Daumier's lithographed plates compiled in 1904 numbers no fewer than 3,958 — he also painted. Except for the searching truthfulness of his vision and the powerful directness of his brushwork, it would be difficult to recognize the creator of Robert Macaire, of Les Bas bleus, Les Bohémiens de Paris, and the Masques, in the paintings of Christ and His Apostles (Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam), or in his Good Samaritan, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, Christ Mocked, or even in the sketches in the Ionides Collection at South Kensington. There is a splendid room-full of caricatures in the gallery "Am Romerholz" at Wintertur.

As a painter, Daumier, one of the pioneers of realistic subjects, but treated with a very subjective point of view, did not meet with success until 1878, a year before his death, when Paul Durand-Ruel collected his works for exhibition at his galleries and demonstrated the range of the talent of the man who has been called the "Michelangelo of caricature". At the time of the exhibition, Daumier was blind and living in a cottage at Valmondois, which Corot placed at his disposal. It was there that he died. He painted about 500 oil paintings.

Legacy

Baudelaire noted of him: l'un des hommes les plus importants, je ne dirai pas seulement de la caricature, mais encore de l'art moderne. (One of the most important men, I will not say only of caricature, but also of modern art.)

An exhibition of his works was held at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1901.

Today, Daumier's works are found in many of the world's leading art museums, including the Louvre, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Rijksmuseum. He is celebrated for a range of works, including a large number of paintings (500) and drawings (1000) some of them depicting the life of Don Quijote, a theme that fascinated him for the last part of his life.

Daumier's 200th birthday was celebrated in 2008 with a number of exhibitions in Asia, America, Australia and Europe.

Gallery

-

Gargantua.

Gargantua.

Litograph, 1831. -

The miller, his son and the donkey, 1849

The miller, his son and the donkey, 1849

-

Crispin and Scapin, 1858-1860.

Crispin and Scapin, 1858-1860.

-

Les Comediens de Société.

Les Comediens de Société.

Lithograph published in Le Charivari, 1858. -

"NADAR élevant la Photographie à la hauteur de l'Art" (NADAR elevating Photography to Art).

"NADAR élevant la Photographie à la hauteur de l'Art" (NADAR elevating Photography to Art).

Lithograph published in Le Boulevard, 1862. -

Les Joueurs d'échecs (The chess players), 1863.

Les Joueurs d'échecs (The chess players), 1863.

Realist painting, oil on canvas, 1863 Petit Palais -

Les Trains de Plaisir (The trains of pleasure).

Les Trains de Plaisir (The trains of pleasure).

Lithograph published in Le Charivari, 1864. -

Une discussion littéraire à la deuxième Galerie (A literary discussion at the second gallery).

Une discussion littéraire à la deuxième Galerie (A literary discussion at the second gallery).

Lithograph published in Le Charivari, 1864. -

Le Wagon de troisième classe (The third-class carriage), 1864.

Le Wagon de troisième classe (The third-class carriage), 1864.

-

La capitulation de Sedan (The capitulation of Sedan).

La capitulation de Sedan (The capitulation of Sedan).

Lithograph published in Le Charivari, 1870. -

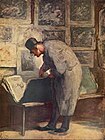

The Print Lover.

The Print Lover.

Painting, c.1857-1860. -

The Laundress

The Laundress

Oil on panel, c.1863. -

Don Quixote and Sancho Panza (1868)

Don Quixote and Sancho Panza (1868)

-

L'Avocat or The Lawyer.

L'Avocat or The Lawyer.

-

L'Avocat au placet or Lawyer with a Plea, c.1850.

L'Avocat au placet or Lawyer with a Plea, c.1850.

-

The Imaginary Invalid (before 1879)

The Imaginary Invalid (before 1879)

Notes

- "Honoré Daumier: A Finger on the Pulse". Hammer.ucla.edu. Retrieved 2013-02-23.

- Rey, page 10.

References

- Rey, Robert, Honoré Daumier, Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 8109-0064-5

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

External links

- Daumier Website, complete website on Daumier's life and work; Bibliography, Exhibitions etc.

- Daumier's biography, style and critical reception

- Web Gallery of Art

- Daumier Lithographs and some information at Brandeis University

- Prints at the Art Institute of Chicago

- Honoré Daumier (French, 1808 - 1879) on MutualArt.com

- Works at the Musée d'Orsay: paintings and especially good selection of sculptures

- Daumier on YouTube a not overly serious travel guide by Daumier

- Daumier on Poverty in YouTube a contribution by the Daumier Register

- Daumier on Sports in YouTube Sport is good for you.... oh, really? a contribution by the Daumier Register

- Daumier an unusual exhibition on YouTube A not so serious guide to an exhibition of 19th century French caricatures by Honoré Daumier, supplied by the Daumier-Register

- Daumier and Max Raabe, two lady-killers on YouTube by the Daumier Register

- Daumier and Max Raabe, the little green cactus on YouTube by the Daumier Register.

- Honoré Daumier at Find a Grave

- Website featuring a selection of Daumier videos by the Daumier Register and 500 photographs of Daumier lithographs

- Daumier Drawings, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF)