| Revision as of 11:17, 14 June 2006 editGiano (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users20,173 edits →Design of the House: cont of re-write of own work← Previous edit | Revision as of 11:19, 14 June 2006 edit undoGiano (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users20,173 editsm →Design of the House: spNext edit → | ||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

| Belton is built of the local ] stone, and designed in the "H" shape and architectural design which became popular in during the late Elizabethan period. However by the late 16th century it had evolved further than the "one room deep" ranges of the earlier houses, such as that at ]. Placing rooms back to back, as at Belton permitted them to be not just better lit and heated but also better accesses and related to each other. Another advantage was that the double room depth allowed the house to be more compact, and under one more easily constructed simple roof. This design also allowed for greater symmetry between the facades. | Belton is built of the local ] stone, and designed in the "H" shape and architectural design which became popular in during the late Elizabethan period. However by the late 16th century it had evolved further than the "one room deep" ranges of the earlier houses, such as that at ]. Placing rooms back to back, as at Belton permitted them to be not just better lit and heated but also better accesses and related to each other. Another advantage was that the double room depth allowed the house to be more compact, and under one more easily constructed simple roof. This design also allowed for greater symmetry between the facades. | ||

| The layout of the rooms at Belton is curious for a great house of the period. Following the restoration of the monarchy, it had become popular for large houses to follow the continental fashion of having a suite of state rooms consisting of a withdrawing room, dressing room and bedroom proceeding from either side of a central saloon or hall <ref>Girouard, Mark (1978). ''Life in the English Country House''.Page 126 Yale University Press. ISBN 0300022735.</ref>. This Baroque arrangement was not employed at Belton, which favoured the older style of having reception rooms and bedrooms scattered over the two main floor. Thus the staircase was designed to be grand and imposing as it was part of the state route from the Hall and Saloon on the first floor to the principal dining room and bedroom on the second. This older concept can be more clearly seen at the Elizabethan ]. However, the lack of a fashionable and formal suite of ] did not prevent a visit from king William III to the newly completed house in 1695. The King occupied the "Best bedchamber" the large room with an adjoining closet, directly above the saloon, leading directly from the second floor Great Dining Chamber. <ref>The King was reported to have enjoyed his stay so much, that the following day he was too hung over to eat any of the food provided on his state visit to ] the following day. Source of this anecdote: The National Trust. Belton House. 2006. Page 49. ISBN 1-84359-218-5</ref> | The layout of the rooms at Belton is curious for a great house of the period. Following the restoration of the monarchy, it had become popular for large houses to follow the continental fashion of having a suite of state rooms consisting of a withdrawing room, dressing room and bedroom proceeding from either side of a central saloon or hall <ref>Girouard, Mark (1978). ''Life in the English Country House''.Page 126 Yale University Press. ISBN 0300022735.</ref>. This Baroque arrangement was not employed at Belton, which favoured the older style of having reception rooms and bedrooms scattered over the two main floor. Thus the staircase was designed to be grand and imposing as it was part of the state route from the Hall and Saloon on the first floor to the principal dining room and bedroom on the second. This older concept can be more clearly seen at the Elizabethan ]. However, the lack of a fashionable and formal suite of ] did not prevent a visit from king William III to the newly completed house in 1695. The King occupied the "Best bedchamber" the large room with an adjoining closet, directly above the saloon, leading directly from the second floor Great Dining Chamber. <ref>The King was reported to have enjoyed his stay so much, that the following day he was too hung over to eat any of the food provided on his state visit to ] the following day. Source of this anecdote: The National Trust. Belton House. 2006. Page 49. ISBN 1-84359-218-5</ref> | ||

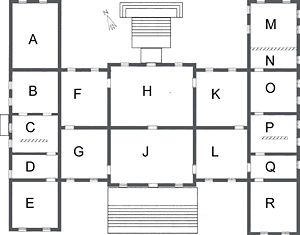

| The principal entrance hall, reception and family bedrooms were placed on the first floor above a low ] containing service rooms. The two principal entrances to the mansion in the centre of both the North and south facades were accessed by external staircases - originally a single broad flight on the north side, and a double staircase on the south. These staircases have since been replaced by the more simple designs illustrated on the plan (''right'') | The principal entrance hall, reception and family bedrooms were placed on the first floor above a low ] containing service rooms. The two principal entrances to the mansion in the centre of both the North and south facades were accessed by external staircases - originally a single broad flight on the north side, and a double staircase on the south. These staircases have since been replaced by the more simple designs illustrated on the plan (''right'') | ||

| ]. The second floor has a matching ] with windows of equal value to those on the first floor below. On these two floors the very latest |

]. The second floor has a matching ] with windows of equal value to those on the first floor below. On these two floors the very latest innovation, sash windows, was used. While the semi-basement and attic storey had the more old fashioned mullioned and transomed windows thus indicating the lower importance of these floors in the social hierarchy of their occupants. Thus the two main floors of the house were purely for state and family use, the staff and service areas being confined to the semi-basement and attic floors. This concept of keeping staff and domestic matters out of site (when not required) was a relatively new concept which had first been employed by Pratt in the design of ] in Berkshire. The contemporary social commentator of the day Roger North lauded back stairs, of which Belton has two examples ('''C & P'''), as one of the most important inventions of his day <ref>Jaskson-Stops, Gervase (1990). ''The Country House in Perspective''. Page 60. Pavilion Books Ltd.</ref>. | ||

| The principal room is the large Marble Hall ('''J''') at the centre of the south front. This room which takes it's name from the black and white marble tiles of its floor is the |

The principal room is the large Marble Hall ('''J''') at the centre of the south front. This room which takes it's name from the black and white marble tiles of its floor is the beginning of a grand procession of room, and corresponds to the former great Parlour or Saloon on the north front. The Marble Hall is flanked by the former Little Parlour ('''G''')(now the Tapestry Room) and the Great Staircase Hall ('''L'''), while the Saloon ('''H''')is flanked by two withdrawing room ('''F & K'''). While the Marble Hall and Saloon were at the centre of an enfilade of reception rooms, they were in no way meant to form the heart of a suite of ]s in the ] fashion. Indeed one of the most important rooms the Great Dining Room (now the library) was quite separate on the floor above directly above the Marble Hall. The bedrooms are arranged in individual suites on both floors of the two wings ('''E * R etc.''') which flank what is sometimes called the "state centre" of the house. The main staircase, set to one side of the Marble Hall, is one of the few things at Belton which as asymmetrically placed. | ||

| == Gardens and the park == | == Gardens and the park == | ||

Revision as of 11:19, 14 June 2006

Belton House is a country house near Grantham, Lincolnshire, England. Today it is owned by the National Trust, and is fully open to the public. The house was built between 1685 and 1688 for Sir John Brownlow. Internally and externally the mansion is considered to be one of the finest examples of Restoration style architecture. During its 300 year history it has been home to the Brownlow family and their descendents the Cust family, who donated the house to the National Trust in 1984. The house retains many of its original furnishings, including plaster work, oriental porcelain, silver. The house is set within formal gardens and a series of avenues leading to garden follies within a greater wooded park.

Early History of Belton

The Brownlow family, a dynasty of lawyers, had begun to accumulate land in the area of Belton from approximately 1598, and the reversion of manor of Belton itself in 1609 from the Pakenham family, who finally sold the manor house to Sir John Brownlow in 1617. However, the old house near the site of the church in the garden of the present house remained largely unoccupied the family preferring their other houses elsewhere. John Brownlow, who had married an heiress, was childless and as a consequence was attached to his only two blood relations a great-nephew, also called, John Brownlow and a great niece Alice Sherard. Following the marriage of the two cousin when both were aged 16 in 1676. Three years later the couple inherited the Brownlow estates from their Great Uncle to together with an income of £9000 per annum and £20,000 in cash. They immediately bought a town house in the newly fashionable Southampton Square in Bloomsbury, and decided to build a new country house at Belton.

In 1685 work on the new house commenced. The architect thought to have been responsible for Belton chosen was Wiliam Winde. This presumption is based on the stylistic similarity between the completed Belton and Coombe Abbey by Winde, and also on a letter dated 1690 in which Winde is recomending a plasterer to complete the interiors. Whoever the architect it seems likely the inspiration for the design of Belton was Clarendon House, London designed by Roger Pratt and completed in 1647. This mansion (demolished soon after 1683) was one of the most admired buildings of its era due to "its elgant symmetry and confident and common sensical design" . However, wat is known for sure is that John and Alice Brownlow employed the master mason Wiliam Stanton to oversee the project, his second in command was John Thompson who had worked with Sir Christopher Wren on several of Wren's London churches, while the chief joiner John Sturges, had worked at Chatsworth under Talman, thus so competent were the builders of Belton, that it is thought Winde may have done little more than provide the original plans and drawings, leaving the interpretation to the master craftsmen. This theory is further born out, by the more provincial, but nevertheless less masterful design of the adjoining stable block which is known to have been entirely the work of Stanton.

Design of the House

Belton is built of the local Ancaster stone, and designed in the "H" shape and architectural design which became popular in during the late Elizabethan period. However by the late 16th century it had evolved further than the "one room deep" ranges of the earlier houses, such as that at Montacute House. Placing rooms back to back, as at Belton permitted them to be not just better lit and heated but also better accesses and related to each other. Another advantage was that the double room depth allowed the house to be more compact, and under one more easily constructed simple roof. This design also allowed for greater symmetry between the facades.

The layout of the rooms at Belton is curious for a great house of the period. Following the restoration of the monarchy, it had become popular for large houses to follow the continental fashion of having a suite of state rooms consisting of a withdrawing room, dressing room and bedroom proceeding from either side of a central saloon or hall . This Baroque arrangement was not employed at Belton, which favoured the older style of having reception rooms and bedrooms scattered over the two main floor. Thus the staircase was designed to be grand and imposing as it was part of the state route from the Hall and Saloon on the first floor to the principal dining room and bedroom on the second. This older concept can be more clearly seen at the Elizabethan Hardwick Hall. However, the lack of a fashionable and formal suite of state apartments did not prevent a visit from king William III to the newly completed house in 1695. The King occupied the "Best bedchamber" the large room with an adjoining closet, directly above the saloon, leading directly from the second floor Great Dining Chamber.

The principal entrance hall, reception and family bedrooms were placed on the first floor above a low semi-basement containing service rooms. The two principal entrances to the mansion in the centre of both the North and south facades were accessed by external staircases - originally a single broad flight on the north side, and a double staircase on the south. These staircases have since been replaced by the more simple designs illustrated on the plan (right)

. The second floor has a matching fenestration with windows of equal value to those on the first floor below. On these two floors the very latest innovation, sash windows, was used. While the semi-basement and attic storey had the more old fashioned mullioned and transomed windows thus indicating the lower importance of these floors in the social hierarchy of their occupants. Thus the two main floors of the house were purely for state and family use, the staff and service areas being confined to the semi-basement and attic floors. This concept of keeping staff and domestic matters out of site (when not required) was a relatively new concept which had first been employed by Pratt in the design of Coleshill House in Berkshire. The contemporary social commentator of the day Roger North lauded back stairs, of which Belton has two examples (C & P), as one of the most important inventions of his day .

The principal room is the large Marble Hall (J) at the centre of the south front. This room which takes it's name from the black and white marble tiles of its floor is the beginning of a grand procession of room, and corresponds to the former great Parlour or Saloon on the north front. The Marble Hall is flanked by the former Little Parlour (G)(now the Tapestry Room) and the Great Staircase Hall (L), while the Saloon (H)is flanked by two withdrawing room (F & K). While the Marble Hall and Saloon were at the centre of an enfilade of reception rooms, they were in no way meant to form the heart of a suite of state rooms in the Baroque fashion. Indeed one of the most important rooms the Great Dining Room (now the library) was quite separate on the floor above directly above the Marble Hall. The bedrooms are arranged in individual suites on both floors of the two wings (E * R etc.) which flank what is sometimes called the "state centre" of the house. The main staircase, set to one side of the Marble Hall, is one of the few things at Belton which as asymmetrically placed.

Gardens and the park

The gardens are expansive, measuring 36 acres (14 ha), and semi-formal, with a wide range of features of various periods and styles. Among the more notable are the orangery and the ice house with its lake.

The park is extensive, including valley bottom and hillside land.

20th century

When the Machine Gun Corps was established in 1915, its home headquarters and base training ground were established in the southern part of the park. The flat bottom and rising sides of the Witham valley here, where the river passes between the Lower Lincolnshire Limestone and the Upper Lias mudstone, made it possible to establish ranges and depot close to good communications in the form of the Great North Road and the east coast main line railway station at Grantham. The depot was closed in 1919 and land was restored to its owner, Lord Brownlow, as the process of removing the temporary buildings progressed.

Trivia

- The house featured as Lady Catherine de Bourgh's residence, Rosings Park, in the BBC's 1995 television version of Pride and Prejudice.

- The house was the setting for the BBC's 1988 adaptation of Moondial.

References

- The National Trust. Belton House. 2006. Page 2. ISBN 1-84359-218-5

- The National Trust. Belton House. 2006. Page 45. ISBN 1-84359-218-5

- This paragraph refering to the input of Winde to the project is the view of Jaskson-Stops, Gervase (1990). The Country House in Perspective. Page 57. Pavilion Books Ltd.

- Girouard, Mark (1978). Life in the English Country House.Page 126 Yale University Press. ISBN 0300022735.

- The King was reported to have enjoyed his stay so much, that the following day he was too hung over to eat any of the food provided on his state visit to Lincoln the following day. Source of this anecdote: The National Trust. Belton House. 2006. Page 49. ISBN 1-84359-218-5

- Jaskson-Stops, Gervase (1990). The Country House in Perspective. Page 60. Pavilion Books Ltd.

External link

This article about a United Kingdom building or structure is a stub. You can help Misplaced Pages by expanding it. |