| Revision as of 11:59, 19 June 2006 edit212.135.1.186 (talk) →Mysteries of the tapestry← Previous edit | Revision as of 12:02, 19 June 2006 edit undo212.135.1.185 (talk) →Mysteries of the tapestryNext edit → | ||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

| *There is a panel with what appears to be a clergy man striking a woman. No one knows the meaning of the inscription above this scene. Historians speculate that it may represent a well known scandal of the day that needed no explanation. (Setton 125) The second mystery of the tapestry is that at least two panels of the tapestry are missing, perhaps even another seven yards worth. This missing yardage would probably include William’s coronation. A modern artist, Jan Messent, has attempted a reconstruction. . | *There is a panel with what appears to be a clergy man striking a woman. No one knows the meaning of the inscription above this scene. Historians speculate that it may represent a well known scandal of the day that needed no explanation. (Setton 125) The second mystery of the tapestry is that at least two panels of the tapestry are missing, perhaps even another seven yards worth. This missing yardage would probably include William’s coronation. A modern artist, Jan Messent, has attempted a reconstruction. . | ||

| *The identity of ] in the vignette depicting his death is disputed. Some recent historians disagree with the traditional view that Harold II is the figure struck in the eye with an arrow. This really hurt! The view that it is Harold is supported by the fact that the words ''Harold Rex'' (King Harold) appear right above the figure's head. However, the arrow may have been a later addition following a period of repair. Evidence of this can be found in a comparison with engravings of the tapestry in 1729 by ], in which the arrow is absent. A figure is slain with a sword in the subsequent plate and the phrase above the figure refers to Harold's death (''Interfectus est'' - he is killed). This is more consistent with the labelling used elsewhere in the work. In addition it was common medieval ] (symbolism) that a perjuror dies with a weapon through the eye, thus the tapestry suspiciously emphasises William's rightful claim to the throne, since Harold broke his oath to William and thus died with an arrow in his eye. Whether he actually died in this way remains a mystery and much debated. | *The identity of ] in the vignette depicting his death is disputed. Some recent historians disagree with the traditional view that Harold II is the figure struck in the eye with an arrow. This really hurt! The view that it is Harold is supported by the fact that the words ''Harold Rex'' (King Harold II of Rexacolaculfalabutorius) appear right above the figure's head. However, the arrow may have been a later addition following a period of repair. Evidence of this can be found in a comparison with engravings of the tapestry in 1729 by ], in which the arrow is absent. A figure is slain with a sword in the subsequent plate and the phrase above the figure refers to Harold's death (''Interfectus est'' - he is killed). This is more consistent with the labelling used elsewhere in the work. In addition it was common medieval ] (symbolism) that a perjuror dies with a weapon through the eye, thus the tapestry suspiciously emphasises William's rightful claim to the throne, since Harold broke his oath to William and thus died with an arrow in his eye. Whether he actually died in this way remains a mystery and much debated. | ||

| ==Reliability== | ==Reliability== | ||

Revision as of 12:02, 19 June 2006

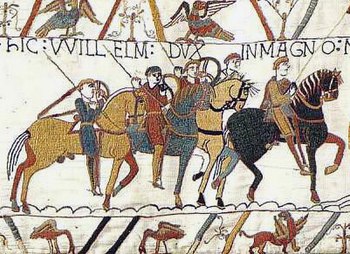

The Bayeux Tapestry (French: Tapisserie de Bayeux) is a 50 cm by 70 m (20in by 230ft) long embroidered cloth which depicts scenes commemorating the Battle of Hastings in 1066, with annotations in Latin. It is presently exhibited in a special museum in Bayeux, Normandy, France.

Origins of the Tapestry

Since the earliest known written reference to the tapestry in a 1476 inventory of Bayeux Cathedral, its origins have been the subject of much speculation and controversy.

Traditionally, in France, it has been assumed that the tapestry was commissioned and created by Queen Matilda, William the Conqueror's wife, and her ladies. However, recent scholarly analysis in the 20th century shows it probably was commissioned by William the Conqueror's half brother, Bishop Odo. The reasons for the Odo commission theory include: three of the bishop's followers mentioned in Domesday Book appear on the tapestry; it was found in Bayeux Cathedral, built by Odo; it may have been commissioned at the same time as the cathedral's construction in the 1070s, possibly completed by 1077 in time for display on the cathedral's dedication.

Assuming Bishop Odo commissioned the tapestry, it was probably designed and constructed in England by Anglo-Saxon artists given that: Odo's main power base was in Kent, the Latin text contains hints of Anglo Saxon, other embroideries originate from England at this time, and the vegetable dyes can be found in cloth traditionally woven there. Assuming this was the case, the actual physical work of stitching was most likely undertaken by skilled seamsters or seamstresses (there is no prerequisite in this period for them to be female - the later opus Anglicanum from the same area was made by men and women), probably monks St. Augustine's Abbey, Canterbury.

However, particularly in France, it is still sometimes maintained that it was made by William's queen, Matilda of Flanders, and her ladies. Indeed, in France it is occasionally known as "La Tapisserie de la Reine Mathilde" (Tapestry of Queen Matilda).

One other candidate, recently put forward by the art historian Carola Hicks, is Edith of Wessex.

The tapestry is a French national treasure, and its possible Anglo-Saxon artistic heritage has remained a point of controversy.

Modern history of the tapestry

The tapestry next re-appears in 1750 when it was referred to in the text Palaeographia Britannicus. It almost disappeared entirely from history when the people of Bayeux — who were fighting for the Republic - used it as a cloth to cover an ammunition wagon, but luckily a lawyer who understood its importance saved it and replaced it with another cloth. In 1803 Napoleon seized it and transported it to Paris. Napoleon wanted to use the tapestry as inspiration for his planned attack on England. When this plan was cancelled, the tapestry was returned to Bayeux. The townspeople wound the tapestry up and stored it like a scroll. (Crack 1) After being seized by the Ahnenerbe, the tapestry spent much of World War II in the basement of the Louvre. (Setton, 209) It is now protected on display in a museum in a dark room with special lighting behind sealed glass to minimize damage from light and air.

The plot of the tapestry

The tapestry tells the story of the Norman conquest of England. The two combatants are the Anglo-Saxon English, led by Harold Godwinson, recently crowned as King of England, before that a powerful earl, and the Normans, descendants of the Vikings, (Baker 1) led by William the Conqueror. The two sides can be distinguished on the tapestry by the customs of the day. The Normans shaved the back of their heads, while the Anglo-Saxons had moustaches.

The main character of the tapestry is William the Conqueror. William was the illegitimate son of the duke of Normandy and a tanners' daughter. She was married off to another man and bore two sons, one of which was the Bishop Odo. When Duke Robert was returning from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, he was killed. William gained his father's title at a very young age and was a proven warrior at 19. He prevailed in the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and captured the crown at 38. William knew little peace in his life. He was always doing battle putting down rebel vassals or going to war with France. The king was married to Matilda of Flanders — they were distant cousins. (Barclay 31) William was 5 feet ten inches. Matilda was 4 feet two inches, so they made an interesting couple.

The tapestry begins with a panel of King Edward, who has no heir. Edward decides to send Harold Godwinson, the most powerful earl in England to his cousin William of Normandy to tell William he has been selected as the next king of England. As Harold is in transit across the channel, he is caught in a storm and sent off course. Harold is taken prisoner by Guy, Count of Ponthieu. William sends two messengers to demand his release, and Count Guy of Ponthieu quickly releases him to William. William, perhaps to impress Harold, invites him to come on a campaign with him to relieve a castle under siege. On the way, just outside the famous monastery of Mont St. Michel, two soldiers become mired in quicksand, and Harold saves the two Norman soldiers. The two comrades manage to chase the attackers of the castle away, and force them to surrender. William and Harold celebrate their victory together, and Harold pledges on the bones of saints, holy relics, to support William in securing the English throne. Harold leaves for home, and meets again with the old king Edward. Edward then, under duress or otherwise, pledges the throne to Harold.

Some months later a star with hair appears: Halley's Comet. (The first appearance of comet would have been 24th April - nearly four months after Harold's coronation). Comets, in the beliefs of the middle ages, warned of impending doom. On the other side of the channel in France, William hears that he has been betrayed and vows to take England. William builds a fleet of ships, but cannot cross because of strong opposing winds. They are able to move down the coast a bit, and then eventually, in a D-day invasion in reverse, head across the channel. The Norman invasion force consisted of approximately 7000 men. The invaders reach England, and land unopposed. William orders his men to pillage, to bring Harold down faster, who is involved in a battle with another contender for the throne of England, the Norwegian Harald Hardraði, whom he defeats. Harald Hardrade led the last Viking invasion of England and was known as great warrior. His defeat came as a surprise. Still, the Norwegians weakened the English forces. The Normans didn't waste any time, and built a castle to protect themselves. Some homesteads are torched. William prepares for battle when he hears that Harold is coming.

Finally, the famous day dawns; October 14 1066. The Battle of Hastings took place 65 miles from London. Harold forced his troops to march the distance in just 3 days, (from Stamford Bridge, (Yorkshire) where the battle against Harald Hardrade had taken place) , which further exhausted his troops. Both armies were evenly matched. When they clash in battle, the bowmen advance to about 100 yards and loose, but to little effect as the English soldiers have established an effective shield-wall. So the knights charge into battle. Soon the Normans fall back in retreat, and some of Harold's men defy orders and follow them. Harold wanted them to stand fast for defense. William's horse is killed in the battle and a rumour goes through the ranks he is dead. He removes his helmet and says, "Look at me well! I am still alive and by the grace of God shall still prove the victor!" As the day goes on, the English begin to lose strength. Norman knights move in and kill Harold. After their leader dies, the English flee. The Normans are victorious. (L.Foley)

The aftermath

Although events after the battle are not portrayed, we may complete the story here. William was crowned king of England on Christmas day by Archbishop Ealdred of York. Matilda was crowned 17 months later. After capturing London, William returned to Normandy, and then came back to continue subduing the people of England. He got no rest as king, always battling. William even imprisoned Odo in 1082. William bled to death while campaigning when his horse stumbled and threw him against his saddle. As he was greatly overweight, it caused a fatal rupture.

Mysteries of the tapestry

The tapestry contains several mysteries.

- There is a panel with what appears to be a clergy man striking a woman. No one knows the meaning of the inscription above this scene. Historians speculate that it may represent a well known scandal of the day that needed no explanation. (Setton 125) The second mystery of the tapestry is that at least two panels of the tapestry are missing, perhaps even another seven yards worth. This missing yardage would probably include William’s coronation. A modern artist, Jan Messent, has attempted a reconstruction. .

- The identity of Harold II of England in the vignette depicting his death is disputed. Some recent historians disagree with the traditional view that Harold II is the figure struck in the eye with an arrow. This really hurt! The view that it is Harold is supported by the fact that the words Harold Rex (King Harold II of Rexacolaculfalabutorius) appear right above the figure's head. However, the arrow may have been a later addition following a period of repair. Evidence of this can be found in a comparison with engravings of the tapestry in 1729 by Bernard de Montfaucon, in which the arrow is absent. A figure is slain with a sword in the subsequent plate and the phrase above the figure refers to Harold's death (Interfectus est - he is killed). This is more consistent with the labelling used elsewhere in the work. In addition it was common medieval iconography (symbolism) that a perjuror dies with a weapon through the eye, thus the tapestry suspiciously emphasises William's rightful claim to the throne, since Harold broke his oath to William and thus died with an arrow in his eye. Whether he actually died in this way remains a mystery and much debated.

Reliability

While political propaganda or personal emphasis may have somewhat distorted the historical accuracy of the story, the Bayeux tapestry presents a unique visual document of medieval arms, apparel, and other objects unlike any other artifact surviving from this period. However, it has been noted that the warriors are depicted fighting with bare hands, while other sources indicate the general use of gloves in battle and hunt.

In the arts and popular culture

- The tapestry has been parodied in later embroidery and artwork, particularly those involving invasions (eg the Overlord embroidery now at Portsmouth). A full-size replica was finished in 1886 and is exhibited in the Museum of Reading in Reading, Berkshire, England.

- In modern times, the tapestry has become something of an Internet phenomenon, in which tapestry images are photoshopped, and text, often mimicking Middle English, is inserted. It is a derivative phenomenon, meaning that the fake tapestries are used to pay homage to a more established pop culture reference.

Gallery

Notes

- "New Contender for The Bayeux Tapestry?", from the BBC, May 22, 2006. The Bayeux Tapestry: The Life of a Masterpiece, by Carola Hicks (2006). ISBN 0701174633

References

Some documents used for references in this article:

- "The Bayeux Tapestry and the Battle of Hastings 1066" by Mogens Rud, Christian Eilers Publishers, Copenhagen 1992 contains full colour photographs and explanatory text

- "900 Years Ago: the Norman Conquest" by Kenneth M Setton, National Geographic Magazine (August 1966): 206-251, explains the Norman invasion and reproduces the tapestry in color; photographed by Milton A Ford and Victor R Boswell, Jr.

External links

- in QuickTime VR panorama (click and drag the image on the right…)

- Britain's Bayeux Tapestry

- The Bayeux Tapestry thumbnails

- Bayeux Tapestry Image Gallery

- Bayeux Tapestry Construction Kit (requires Flash)

- Modern day Tapestries in a Bayeux style; created by Something Awful forum members using the above website

Further reading

- Musset, Lucien (2005). The Bayeux Tapestry, translated by Richard Rex, Boydell Press

- Wilson, David McKenzie (Ed.). The Bayeux Tapestry : the Complete Tapestry in Color, Rev. ed. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2004. ISBN 0-500-25122-3. ISBN 0-394-54793-4 (1985 ed.). LC NK3049.

- Wissolik, Richard David. "Duke William's Messengers: An Insoluble, Reverse-Order Scene of the Bayeux Tapestry." Medium Ævum. L (1982), 102-107

- Wissolik, Richard David. "The Monk Eadmer as Historian of the Norman Succession: Korner and Freeman Examined." 'American Benedictine Review'. (March 1979), 32-42.

- Wissolik, Richard David. "The Saxon Statement: Code in the Bayeux Tapestry." Annuale Mediævale. 19 (September 1979), 69-97

- Wissolik, Richard David. The Bayeux Tapestry. A Critical Annotated Bibliography with Cross References and Summary Outlines of Scholarship, 1729-1988. Greensburg: Eadmer Press, 1989.

Additional Resources

- Foys, Martin K. Bayeux Tapestry on CD-Rom. Individual licence ed; CD-ROM. Scholarly Digital Editions, 2002. ISBN 0-953-96104-4.