| Revision as of 22:17, 9 March 2014 editClueBot NG (talk | contribs)Bots, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers6,438,209 editsm Reverting possible vandalism by 67.149.26.178 to version by AddWittyNameHere. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (1736405) (Bot)← Previous edit | Revision as of 17:58, 31 March 2014 edit undo50.79.182.145 (talk) →From Indentured Servant to SlaveTag: blankingNext edit → | ||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

| ==From Indentured Servant to Slave== | ==From Indentured Servant to Slave== | ||

| slavery.<ref>{{Cite journal |title=History of Black Americans: From Africa to the emergence of the cotton kingdom |first=Philip S. |last=Foner |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=1980 |url=http://testaae.greenwood.com/doc_print.aspx?fileID=GR7529&chapterID=GR7529-747&path=books/greenwood}}</ref> | |||

| Early cases demonstrate how Negro servants were treated differently from their Caucasian indentured allies. In 1640, the General Virginia Court decided the Emmanuel case. Emmanuel was a negro servant who participated in a plot to escape along with six white servants. Together, they stole corn, powder, and shot guns but were caught before making their escape. The group was convicted and sentenced with a variety of punishments. Christopher Miller, the leader of the group, was sentenced to wear shackles for one year. Another white servant, John Williams, was sentenced to serve the colony for an extra seven years. Peter Willcocke was branded, whipped, and was required to serve the colony for seven years. Richard Cookson was required to serve for two additional years. Emmanuel, the Negro, was whipped and branded with an "R" on his cheek. All of the white servants got their terms of servitude increased by some extent while the court didn't extend Emmanuel's time of service. Many historians speculate Emmanuel was, most likely, already a servant for life and therefore couldn't have his servitude extended. This case shows a clear difference in how white servants and black servants were treated, though it is not certain if Emmanuel was a servant for life or not. Though this case gives the implication of slavery, the distinction of lifetime servitude or slavery wouldn't appear until later.<ref>{{Cite book |title=In the Matter of Color: Race and the American Legal Process: The Colonial Period |first=A. Leon |last=Higginbotham |publisher=Greenwood Press |date=1975 |url=http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=ErPg7VegkcMC&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=%22john+punch%22+higginbotham&ots=RD8BjPWEsA&sig=rqEqTivBBg9I3VfMuRS48157bPQ#v=onepage&q=%22john%20punch%22&f=false}}</ref> | |||

| That same year, 1640, "the first definite indication of outright enslavement appears in Virginia."<ref>{{Cite book |title=White Over Black: American attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550-1812 |first=Winthrop |last=Jordan |publisher=University of North Carolina Press |date=1968 |url=http://www.amazon.com/White-Over-Black-Attitudes-1550-1812/dp/0807871419}}</ref> ], a Negro, escaped from his master, Hugh Gwyn, along with two white servants. Hugh Gwyn petitioned the courts and the three servants were captured, convicted, and sentenced. The white servants had their indentured contracts extended by four years but the courts gave John Punch a much harsher sentence. The courts decided that "the third being a negro named John Punch shall serve his said master or his assigns for the time of his natural life here or else where." This is the earliest legal documentation of slavery in Virginia and marked not only racial disparity between black servants and their white counterparts, but also the beginning of Virginian courts systematically reducing Negros from a condition of indentured servitude to that of slavery. It was clear that the colony was becoming comfortable with forcing Negro laborers to serve for the remainder of their lives.<ref>{{Cite book |title=In the Matter of Color: Race and the American Legal Process: The Colonial Period |first=A. Leon |last=Higginbotham |publisher=Greenwood Press |date=1975 |url=http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=ErPg7VegkcMC&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=%22john+punch%22+higginbotham&ots=RD8BjPWEsA&sig=rqEqTivBBg9I3VfMuRS48157bPQ#v=onepage&q=%22john%20punch%22&f=false}}</ref> | |||

| Some Negro servants were forced to serve for life by masters who simply refused to acknowledge the expiration of their indentured contracts. One well known example of this was ] and his indentured servant, ]. Anthony Johnson was one of 20 black men brought to Jamestown in 1619 as ]s. By 1623, he had achieved his freedom and by 1651 was prosperous enough to import five "servants" of his own, for which he was granted {{convert|250|acre|km2}} as "headrights".<ref>"Virginia, Guide to the Old Dominion", WPA Writers' Program, Oxford University Press, NY 1940</ref> One of his servants was John Casor. John Casor alleged that he had come to Virginia as an indentured servant, and attempted to transfer his obligation to a white farmer named Robert Parker. However, Anthony Johnson claimed that "hee had ] Negro for his life". In the lawsuit of ''Johnson vs. Parker'', the court in Northampton County ruled that "seriously consideringe and maturely weighing the premisses, doe fynde that the saide Mr. Robert Parker most unjustly keepeth the said Negro from Anthony Johnson his master....It is therefore the Judgement of the Court and ordered That the said John Casor Negro forthwith returne unto the service of the said master Anthony Johnson, And that mr. Robert Parker make payment of all charges in the suit." Casor was thus returned to Johnson and served him for the rest of his life. | |||

| There is more evidence that Virginia Negros were serving for life in the 1650s. In 1660 the Assembly stated that “in case any English servant shall run away in company with any Negroes who are incapable of making satisfaction by addition of time… shall serve for the time of the said Negroes absence.” This statute indicates quite clearly that Negroes served for life and hence could not make “satisfaction” by serving longer once they were recaptured. This phrase gave legal status to the already existing practice of lifetime enslavement of Negroes. However, statutes would soon start to define slavery as more than merely lifetime slavery.<ref>{{Cite journal |title=History of Black Americans: From Africa to the emergence of the cotton kingdom |first=Philip S. |last=Foner |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=1980 |url=http://testaae.greenwood.com/doc_print.aspx?fileID=GR7529&chapterID=GR7529-747&path=books/greenwood}}</ref> | |||

| ==Slavery becomes an institution== | ==Slavery becomes an institution== | ||

Revision as of 17:58, 31 March 2014

The History of slavery in Virginia can be traced back to the very founding of Virginia as an English colony by the London Virginia Company. The headright system tried to solve the labor shortage by providing colonists with land for each indentured servant they transported to Virginia. African workers were first imported in 1619, and their slavery was codified after a 1654 lawsuit over the servant John Casor.

Indentured servants

Nicholas Ferrar wrote a contemporaneous text Sir Thomas Smith's Misgovernment of the Virginia Company (first published by the Roxburghe Club in 1990). Here he lays charges that Smith and his son-in-law, Robert Johnson, were running a company within a company to skim off the profits from the shareholders. He also alleged that Dr. John Woodall had bought some Polish settlers as slaves, selling them on to Lord de La Warr. He claimed that Smith was trying to reduce other colonists to slavery by extending their period of indenture indefinitely beyond the seventh year.

In 1650, there were only about 300 "Africans" living in Virginia, about 1% of an estimated 30,000 population. They were not slaves, any more than were the approximately 4000 white indentured servants working out their loans for passage money to Virginia. Many had earned their freedom, and they were each granted 50 acres (200,000 m) of land when freed from their indentures, so they could raise their own tobacco or other crops. Although they were at a disadvantage in that they had to pay to have their newly acquired land surveyed in order to patent it, white indentured servants found themselves in the same predicament. Some black indentured servants, however, went on to patent and buy land. Anthony Johnson, who settled on the Eastern Shore following the end of indenture, even bought African slaves of his own. George Dillard, a white indentured servant who settled in New Kent County after his servitude ended, held at least 79 acres (320,000 m) of his own land and was able to marry despite a dearth of women in the colonies at that time.

From Indentured Servant to Slave

slavery.

Slavery becomes an institution

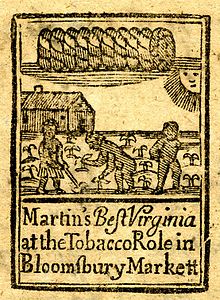

Increasingly toward the end of the 17th century, large numbers of slaves from Africa were brought by Dutch and English ships to the Virginia Colony, as well as Maryland and other southern colonies. On the large tobacco plantations, as chattel (owned property), they replaced indentured servants (who were only obligated to work for an agreed period of time) as field labor, as well as serving as household and skilled workers. As slaves, they were not working by mutual agreement, nor for a limited period of time. In time the practice of slavery became an economic factor for the labor-intensive tobacco and cotton plantations of the South.

Partus sequitur ventrem

Prior to the adoption of the doctrine partus sequitur ventrem (partus) in the English colonies in 1662, beginning in Virginia, English common law had held that among English subjects, a child's status was inherited from its father. The community could require the father to acknowledge illegitimate children and support them. In 1658, Elizabeth Key was the first woman of African descent to bring a freedom suit in the Virginia colony, seeking recognition as a free woman of color, rather than being classified as a Negro (African) and slave. Her natural father was an Englishman (and member of the House of Burgesses). He had acknowledged her, had had her baptized as a Christian in the Church of England, and had arranged for her guardianship under an indenture before his death. Her guardian returned to England and sold the indenture to another man, who held Key beyond its term. When he died, the estate classified Key and her child (also the son of an English subject) as Negro slaves. Key sued for her freedom and that of her infant son. She won her case.

While the demands of labor led to importing more African slaves, the number of indentured servants declined in the late seventeenth century, related to conditions both in England and the colonies. Against this background, the new legal doctrine of partus was made part of colonial law passed in 1662 by the Virginia House of Burgesses, and by other colonies soon after. It held that "all children borne in this country shall be held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother..." As at the time, most bond women were African and considered foreigners, their children likewise were considered foreigners and removed from consideration as English subjects. The racial distinction made it easier to identify them, and slavery became a racial caste associated with Africans regardless of the proportion of English or European ancestry that children inherited from paternal lines. The principle became incorporated into state law when Virginia achieved independence from Great Britain.

The partus doctrine may have originated in the economic needs of the colony with its perpetual labor shortages. Conditions were difficult, mortality was high, and the government was having difficulty attracting sufficient numbers of indentured servants. The change also gave cover to the power relationships by which white planters, their sons, overseers and other white men took sexual advantage of enslaved women. Their illegitimate mixed-race children were now "confined" to slave quarters, unless fathers took specific legal actions on their behalf. The new law in 1662, meant that white fathers were no longer required to legally acknowledge, support, or emancipate their illegitimate children by slave women. Men could sell their issue or put them to work.

Freedom for some slaves

Almost as soon as the practice of slavery was established in Virginia, some individual slaves began obtaining their freedom. This was usually accomplished by escape, through their own enterprise, or through benevolence of their "owners", as family-type ties grew between some of them. Many escaped slaves lived freely as part of the community of Great Dismal Swamp maroons. Other escaped slaves traveled to non-slave Colonies (and later states) to the North, often via the Underground Railroad. However, many of the black men and women who had legally gained their freedom chose to stay in the South. Known as freedmen, they lived at various locations throughout the area.

In the 19th century

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2013) |

At the time of the American Revolutionary War, what was later called the "peculiar institution" of slavery was an unresolved issue between the 13 Colonies. However, the fundamental basis for its demise was laid by the country's founding fathers in both the Declaration of Independence and the new U.S. Constitution.

The 19th century saw two major attempted slave revolts in Virginia: Gabriel's Rebellion in 1800 and Nat Turner's slave rebellion in 1831.

In 1849, slave Henry "Box" Brown escaped from slavery in Virginia when shipped himself in a crate to Philadelphia.

Emancipation

Slavery was to become a growing conflict between the states as the new United States grew, until the mass emancipation of all of the remaining slaves took place during the years of the American Civil War (1861–1865) and immediately thereafter.

See also

References

- Hashaw, Tim (2007). The Birth of Black America. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. pp. 76–77, 211–212, 239–240. ISBN 0-7867-1718-1.

- Billings, Warren (2009). The Old Dominion in the Seventeenth Century: A Documentary History of Virginia, 1606–1700. pp. 286–287. ISBN 1-4429-6126-0.

- Sir Thomas Smith's Misgovernment of the Virginia Company. By Nicholas Ferrar. A Manuscript from the Devonshire Papers at Chatsworth House. Edited with an introduction by D. R Ransome. Roxburghe Club, 1990. Unpublished. Presented to the Members by the Duke of Devonshire.

- 9Nell Marion Nugent, Cavaliers and Pioneers: Abstracts of Virginia Land Patents and Grants, 1623-1666, with Introduction by Robert Armistead Stewart (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1963 , originally published Richmond, VA: 1934), pp. 194-195, in Patent Book 2, p. 231. Hereinafter , Nugent, C&P 1:194, PB 2: 231; and a later volume by Nugent--Cavaliers and Pioneers. . . , 1666-1695, Vol. 2, (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1977): Nugent, C&P 2: 240, PB 7: 173; 2: 259, PB 3: 99; 2; 341-342, PB 8:37, 42; and 2: 386, PB 8, 320.

- Foner, Philip S. (1980). "History of Black Americans: From Africa to the emergence of the cotton kingdom". Oxford University Press.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Taunya Lovell Banks, "Dangerous Woman: Elizabeth Key's Freedom Suit -Subjecthood and Racialized Identity in Seventeenth Century Colonial Virginia", 41 Akron Law Review 799 (2008), Digital Commons Law, University of Maryland Law School, accessed 21 Apr 2009 Cite error: The named reference "Banks" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Frank W. Sweet, "The Transition Period", Backintyme Essays, accessed 21 Apr 2009

- ^ Kolchin, Peter American Slavery, 1619-1877, New York: Hill and Wang, 1993, p. 17