| Revision as of 23:29, 19 April 2014 editWinkelvi (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers30,145 edits →Overview: ce to remove extraneous commentary that really made no sense← Previous edit | Revision as of 23:31, 19 April 2014 edit undoWinkelvi (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers30,145 edits Undid revision 604946403 by Forestrystudent (talk)rev back to NPOV referenceNext edit → | ||

| Line 720: | Line 720: | ||

| |author = Forest Practices Board | |author = Forest Practices Board | ||

| |publisher = ] | |publisher = ] | ||

| |url = http://www.dnr.wa.gov/BusinessPermits/Topics/ForestPracticesRules/Pages/fp_rules.aspx | |||

| |url = http://washingtondnr.wordpress.com/2014/03/27/sr-530-landslide-questions-answers-about-landslides-and-geology/ | |||

| |accessdate = 31 March 2014 | |accessdate = 31 March 2014 | ||

| }} | }} | ||

Revision as of 23:31, 19 April 2014

| File:Oso landslide (WSP).pngOso mudslide, looking northwest | |

| Date | March 22, 2014 (2014-03-22) |

|---|---|

| Time | 10:37 a.m. |

| Location | Oso, Washington |

| Coordinates | 48°16′57″N 121°50′53″W / 48.28256°N 121.84800°W / 48.28256; -121.84800 |

| Cause | Suspected soil saturation from heavy rainfall. |

| Deaths | 39 |

| Non-fatal injuries | 4 serious |

| Missing | 4 |

| Property damage | 49 homes and other structures destroyed |

On Saturday, March 22, 2014, at 10:37 a.m. local time, a major mudslide occurred 4 miles (6.4 km) east of Oso, Washington, United States, when a portion of an unstable hill collapsed, sending mud and debris across the North Fork of the Stillaguamish River, engulfing a rural neighborhood, and covering an area of approximately 1 square mile (2.6 km). As of April 17, 2014, the Snohomish County Medical Examiner's office confirms 39 people have died and 4 people remain missing as a result of the slide.

Overview

The March 2014 landslide engulfed 49 homes and other structures in an unincorporated neighborhood known as "Steelhead Haven" 4 mi (6.4 km) east of Oso, Washington. It also dammed the river, causing extensive flooding upstream as well as blockiing State Route 530, the main route to the town of Darrington (population 1,347). The geologic feature that includes the most recent activity is known as the Hazel Landslide, with the latest event being referred to by the press as "the Oso mudslide". Excluding landslides caused by volcanic eruptions, earthquakes or dam collapses, the Oso slide is the deadliest single landslide event in United States history.

The Hazel Landslide has a history of instability dating back to 1937. Prior to the March 2014 mudslide, the Oso area experienced up to 200 percent normal rainfall over the previous 45 days. The slide was described by witnesses as a "fast-moving wall of mud" containing trees and other debris cutting through homes directly beneath the hill. A firefighter at the scene stated, "When the slide hit the river, it was like a tsunami". A Washington state geologist stated the slide was one of the largest landslides he had personally seen. The mud, soil and rock debris left from the mudslide covered an area 1,500 ft (460 m) long, 4,400 ft (1,300 m) wide and deposited debris 30 to 70 ft (9.1 to 21.3 m) deep.

Casualties and damage

More than 100 first responders from Snohomish and surrounding counties were dispatched to assist with emergency medical and search-and-rescue efforts, including the Navy's search and rescue unit stationed at nearby Naval Air Station Whidbey Island. As of March 30, 2014 approximately 620 personnel, including 160 volunteers, had been working on landslide recovery operations.

Late in the evening of March 22, 2014, Washington Lieutenant Governor Brad Owen declared a state of emergency in Snohomish County. Governor Jay Inslee toured the area by air the following day before joining county officials at a news conference.

On the day of the slide, eight people were rescued and taken to regional hospitals. As of April 17, 2014, the Snohomish County Medical Examiner's office had officially confirmed 39 fatalities with four people still listed as missing. As of April 7, 2014, four survivors of the slide were still in Seattle-area medical facilities: three at Harborview Medical Center with two of those in intensive care and one released to a rehabilitation facility.

The slide blocked the North Fork of the Stillaguamish River, causing it to back up eastward. Because of concerns that the mud and debris dam could fail, causing downstream flooding, a flash flood watch was issued by the National Weather Service. On April 2, with the river flowing in a new channel at the north end of the debris dam, the flash flood watch was lifted. Flooding due to the partially obstructed river continued upstream of the debris dam. Following the slide, State Route 530 was closed indefinitely by the Washington State Department of Transportation with an alternative route around the slide opened when snow was cleared from the unpaved portion of Mountain Loop Highway south of Darrington.

Federal aid

On April 3, the mudslide was declared a major disaster by President Barack Obama. The declaration was requested on April 1 by Governor Inslee, who said that about 30 families needed help with housing and other needs. Inslee further stated that estimated that financial losses had reached $10 million. Snohomish County Emergency Management Director John Pennington advised residents to register with FEMA. Four days later, during the passing of the Green Mountain Lookout Heritage Protection Act, the landslide was publicly mentioned by Senator Patty Murray (D-WA), saying the bill would "provide a glimmer of hope for the long-term recovery of this area."

Controversy

"Completely unforeseen"

On March 24, two days after the slide, John Pennington, Director of Snohomish County's Department of Emergency Management, stated at a news conference, "This was a completely unforeseen slide. This came out of nowhere." The same day the Seattle Times published an article about previous slides at the same location, as well as the likelihood of future slides. The article contained comments from geologists, engineers, and local residents, and stated that the area was known among locals as "Slide Hill". On the next day the Times followed up with a full page article, "'Unforeseen' risk of slide? Warnings go back decades". Snohomish County Public Works Director Steve Thomsen was quoted as saying, "A slide of this magnitude is very difficult to predict. There was no indication, no indication at all."

On March 27, 2014, the Seattle Times reported that a 2010 study, commissioned by the county, warned the hillside above Steelhead Drive was one of the most dangerous in the county. According to one of the authors of the 2010 report, "For someone to say that this plan did not warn that this was a risk is a falsity." In the days following the slide, criticism of Snohomish County officials received national attention in a New York Times editorial. The Seattle Times further reported that in 2004, county officials became concerned about the possibility of a dangerous landslide in the Steelhead Haven area, and considered buying out the homes of that area's residents. The idea was rejected with the county building a new wall in an attempt to stabilize the slope. Some disaster experts criticized this decision as a serious mistake. According to environmental engineer and applied geomorphologist Tracy Drury, " didn't even stop pounding nails." As to any kind of buy-out program, Drury further stated, "I think we did the best we could under the constraints that nobody wanted to sell their property and move elsewhere."

Repairs to the slide area extend back several decades prior to the March 2014 slide. A rock revetment installed in 1962 to protect the toe of the slide area from erosion from the river was overrun by a slide two years later. An effort in 2006 to move the river 430 feet south of the erosion area failed when another landslide moved the river a total of 730 feet.

Logging

In the days following the slide, scientists questioned whether logging in the area could have been a factor contributing to the hillside collapse. Grandy Lake Forest Associates of Mount Vernon, Washington proposed a 15-acre clearcut at the upper edge of the Oso landslide zone in 2004. Washington state forester Aaron Everett stated in an interview with KUOW that the application was rejected and "The one that was approved in the end eliminated the part of the harvest that would have been inside the groundwater recharge area." Everett further stated the resulting 7-acre clearcut operation reached to the edge of the groundwater danger zone. An investigation is being conducted to determine whether Grandy Lake crossed into the restricted area that could theoretically feed groundwater into the landslide zone, affecting it for 16 to 27 years.

Ground activity surrounding the slide

Ground vibrations generated by the Oso landslide were recorded at several regional stations and subsequently analyzed by the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network (PNSN). The initial collapse began at 10:37:22 a.m. local time (PDT; 17:37:22 UTC), lasting approximately 2.5 minutes. Debris loosened by initial collapse is believed to containt material previously disturbed and weakened by the 2006 slide. Following the initial event was another large slide occurring at 10:41:53 PDT. Additional events, most likely smaller landslides breaking off the headscarp, continued for several hours. The last notable signal came at 14:10:15. Examination of records from the nearest seismic station 7 mi (11 km) to the southwest indicate small seismic events started around 8 a.m. the day of the slide and stopped in the late afternoon,However, they were not detected at the next nearest seismic station. They are also seen in the days before and after the slide, but only during daylight hours. They are believed to be related to some kind of human activity. No other indications of possible precursors have been found.

In the days following the slide, Snohomish County Emergency Management Director John Pennington speculated a 1.1 magnitude earthquake on March 10 may have triggered the landslide. Data collected by the PNSN shows a magnitude 1.1 earthquake on that date in the vicinity of the Oso landslide (about 2 ±0.8 km to the northeast), at a depth of 3.9 ±1.9 km. Regardless, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) determined the slide was not caused by seismic activity.

Geological context

The landslide occurred at the southeastern edge of Whitman Bench, a land terrace about 800 ft (240 m) above the valley floor and consisting of gravel and sand deposited during the most recent glaciation. When the Puget Lobe of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet moved south from British Columbia, Canada filling the Puget Lowland, various mountain valleys were dammed and lakes were formed. Sediment washed down from the higher mountains settled in the lake bottoms forming a layer of clay. As the glacial ice pressed higher against the western end of Mount Frailey, water flowing around the edge of the ice from the north was forced around the mountain, eventually pouring in through the long valley extending to the northwest and now occupied by Lake Cavanaugh. Sand and gravel carried by the flow and entering the glacial lake dropped out to form a delta, the remnant of which is now known as Whitman Bench.

Following the glacier's retreat and allowing for the lake to be released, the river carved out most of the clay and silt deposits, leaving the former delta "hanging" approximately 650 ft (200 m) above the current valley floor. When the sand portion of a deposit has very little clay or "fines" to cement it together, it is structurally weak, leaving the area around it vulnerable. Such an area is also sensitive to water accumulation, increasing the internal "pore" pressure and subsequently contributing to ground failure. Water infiltrating from the surface will flow through the surface, save for contact with the less permeable clay, allowing the water to accumulate and form a zone of stability weakness.Such variations in pore pressure and water flux are one of the primary factors leading to slope failure. In case of the area of the Stillaguamish River where the March 2014 slide occurred, erosion at the base of the slope from the river flow further contributes to slope instability. Such conditions have created an extensive series of landslide complexes on both sides of the Stillaguamish valley. Additional benches on the margin of Whitman Bench are due to deep-seated slumping of large blocks, which also creates planes of weakness for future slippage and channels for water infiltration.

History of slide activity

According to a 1999 report submitted to the Army Corps of Engineers by geologist Daniel J. Miller, Ph.D.:

The Hazel landslide has been active for over half a century. Thorsen (1996) noted a tight river bend impinging on the north bank with active landsliding visible in 1937 aerial photographs. The next 60 years involves two periods of relatively low landslide activity, and two periods of relatively high activity, the last of which extends to this day .

Known activity at this specific site includes the following:

- 1937: aerial photographs show active landsliding.

- 1951: mudflow from a side channel briefly blocked the river.

- 1952: movement of large, intact blocks, leaving headscarps 70 ft (21 m) high. Later photographs show persistent activity through the next decade.

- 1967 January: slump of a large block and accompanying mud flows push the river channel about 700 ft (210 m) south. This protects the toe from erosion, activity is minor for about two decades.

- 1988 November: erosion of the toe leads to another slide, and the river is again moved south, but not as far as in 1967.

- 2006 January 25: large slide blocks the river, new channel is cut to alleviate flooding.

See also

Notes

- ^ Washington Post, March 24, 2014.

- ^ Snohomish County Medical Examiner’s Office (April 16, 2014). "Snohomish County Medical Examiner's Office Media Update". Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- ^ Seattle Times, April 7, 2014.

- ^ Snohomish County Sheriff's Office (April 17, 2014). "SR 530 Slide Area Missing Person List". Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- ^ Seattle Times, March 24, 2014c

- Herald (Everett), March 22, 2014; Leberfinger 2014; NBC News, March 24, 2014; Seattle Times, March 22, 2014.

- "Worst Landslides in U.S. History". Wunderground. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- Seattle Times, March 24, 2014a; Miller & Sias 1998.

- Seattle Times, March 24, 2014a; Miller & Sias 1998.

- Leberfinger 2014.

- Q13 Fox; "The mud and debris are 70 feet deep in some places"; Tina Patel

-

- Fresh landslide tailings depicted in aerial photograph dated 2006, with topology map comparisons (1901–1977) at NETROnline.com.

- KING5 News Online, March 23, 2014.

- Seattle Times, March 23, 2014b.

- "Death toll rises to 14 in Snohomish County landslide". KING 5 News and Associated Press. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- Whidbey News Times, March 26, 2014; Herald (Everett), March 22, 2014; Leberfinger 2014; NBC News, March 24, 2014; Seattle Times, March 22, 2014.

- Snohomish County Medical Examiner’s Office (April 1, 2014). "Sunday night 530 landslide update".

- "Landslide kills three, injures others in Washington state". Reuters. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- "Flash Flood Watch". National Weather Service. Retrieved March 27, 2014.

- "SR 530 Landslide". Washington State Department of Transportation. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- "Obama declares major disaster for Oso landslide", KING 5 News and Associated Press via kvue.com, April 3, 2014. Retrieved 2014-04-03.

- Cox, Ramsey (April 3, 2014). "Senate approves small bill to help Oso recovery". The Hill. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- Seattle Times, March 25, 2014a.

- Seattle Times, March 24, 2014a.

- Seattle Times, March 25, 2014a.

- Seattle Times, March 27, 2014.

- Rob Flaner, quoted in Seattle Times, March 27, 2014.

- New York Times, March 29, 2014b.

- Christian Science Monitor, April 5, 2014.

- Seattle Times, March 25, 2014a.

- Seattle Times, March 25, 2014a.

- UPI Science News; "Logging may have contributed to deadly Washington landslide"

- Concern Over Landslide-Logging Connection Near Oso Is Decades Old

- "Oso: Clearcut Extended Into No-Logging Zone | Northwest Public Radio". Nwpr.org. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- Mike Baker and Justin Mayo (March 26, 2014). "Logging OK'd in 2004 may have exceeded approved boundary". Seattle Times.

- Allstadt 2014.

- ^ Allstadt 2014 (PNSN).

- Seattle Times, March 25, 2014c; CBC News, March 25, 2014.

- M1.1 - 18km WNW of Darrington, Washington (BETA)

- USGS states slide not caused by seismic activity

- Miller 1999, p. 1; USGS OFR 2014-1065.

- Tabor et al. 2002 (Sauk River Quadrangle).

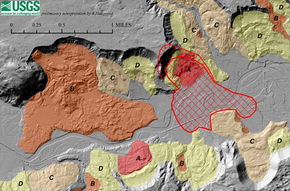

- The areas predominantly containing gravel and sand are shown as "Qgoge" and "Qgose", respectively. "Qgle" and "Qglv" mark exposures of the underlying clay and silt with "Qls" marking landslide complexes. Mount Higgins; Dragovich & Stanton 2007 (DDMF).

- Miller 1999, p. 1.

- Miller 1999, p. 1.

- Miller 1999, p. 4.

- Miller & Sias 1997, Figure 1.3.

- Miller 1999, p. 2.

- Geologist Daniel J. Miller Ph.D. curriculum vitae online

- Miller 1999, pp. 2–3.

- Seattle Times, January 27, 2006. See also Steelhead Landslide pictures.

References

- Allstadt, Kate (March 26, 2014), "Seismic signals generated by the March 22nd Oso Landslide", Seismo Blog: Updates and dispatches from the PNSN.

- Bellingham Herald: Stark, John (January 23, 2009). "Lands commissioner tours landslide areas in Whatcom County". The Bellingham Herald. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- Benda, L.; Thorsen, G.; Bemath, S. (1988). "Report of the ID Team Investigation of the Hazel Landslide on the North Fork of the Stillaguamish River". Unpublished. DNR NW Region, FPA: 19–09420.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- CBC News: Lanela, Mike (March 25, 2014). "Washington state mudslide preceded by small earthquake". CBC News.

- Christian Science Monitor:

- Knickerbocker, Brad (March 28, 2014). "Washington mudslide: logging eyed as contributing cause". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- Knickerbocker, Brad (April 5, 2014). "Authorities knew of mudslide danger, but didn't tell residents". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- Dragovich, Joe D.; Stanton, Benjamin (2007), "The Darrington—Devils Mountain Fault — A probably active reverse-oblique-slip fault zone in Skagit and Island Counties, Washington", Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources, Open-File Report 2007-2, 1 sheet, scale 1:31,104.

- Dragovich, Joe D.; Stanton, Benjamin W.; Griesel, Gerry A.; Polenz, Michael (2003), "Geologic Map of the Mount Higgins 7.5-minute Quadrangle, Skagit and Snohomish Counties, Washington" (PDF), Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources, Open-File Report 2003-12, 1 sheet, scale 1:24,000

{{citation}}:|first3=missing|last3=(help).

- Haugerud, Ralph A. (2014), "Preliminary interpretation of pre-2014 landslide deposits in the vicinity of Oso, Washington" (PDF), U.S. Geological Survey, Open-File Report 2014-1065, doi:10.3133/ofr20141065.

- Herald (Everett, Washington): Winters, Chris (March 22, 2014). "Mudslide witness: 'Everything was gone in 3 seconds'". Everett Herald. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- KING 5 News (Seattle):

- "Death toll rises to 14 in Snohomish County landslide". KING 5 News. Associated Press. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Arab, Zahid (March 23, 2014). "What caused the landslide near Oso?". KING5 News Online. Seattle, Washington: King5.com. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- "Death toll rises to 14 in Snohomish County landslide". KING 5 News. Associated Press. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- KUOW (Seattle): Ryan, John (March 26, 2014). "Concern Over Landslide-Logging Connection Near Oso Is Decades Old". KUOW. Seattle, Washington. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Leberfinger, Mark (March 24, 2014). "Death Toll From Washington Landslide Climbs to Eight". AccuWeather.com. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Miller, Daniel J. (October 1999), Hazel/Gold Basin Landslides: Geomorphic Review Draft Report (PDF).

- Miller, Dan; Sias, Joan (1997), Environmental Factors Affecting the Hazel Landslide (PDF).

- Miller, Daniel J.; Sias, Joan (1998). "Deciphering large landslides: linking hydrological, groundwater and slope stability models through GIS" (PDF). Hydrological Processes. 12 (6): 923–941.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- NBC News: Fieldstadt, Elisha; Smith, Alexander (March 24, 2014). "Rescuers Search 'Quicksand' for Survivors of Washington Mudslide". NBC News. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- Schwartz, John (March 29, 2014a). "No Easy Way to Restrict Construction in Risky Areas". The New York Times. p. A12.

- Egan, Timothy (March 29, 2014b). "A Mudslide, Foretold". The New York Times. p. SR3.

- Kaminsky, Jonathan (March 23, 2014). "Landslide kills three, injures others in Washington state". Reuters. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Ryan, John (March 28, 2014). "Oso: Clearcut Extended Into No-Logging Zone". Northwest Public Radio. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- The Seattle Times (by date):

- Alexander, Brian (January 27, 2006). "Slide diverts river; Oso homes at risk". The Seattle Times.

- Bernton, Hal; Mayo, Justin (July 13, 2008). "Logging and landslides: What went wrong?". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- Bernton, Hal; Mayo, Justin (July 14, 2008). "Slides putting our highways in danger". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- Gonzalez, Angel; Garnick, Coral; Broom, Jack (March 22, 2014). "3 die in mudslide east of Arlington, 6 homes destroyed". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- Gonzalez, Angel; Garnick, Coral; Broom, Jack (March 23, 2014a). "3 die in mudslide east of Arlington, 6 homes destroyed". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- "8 confirmed dead in mudslide; 18 still missing". The Seattle Times. March 23, 2014b. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- Bartley, Nancy; Armstrong, Ken (March 24, 2014a). "Site has long history of slide problems". The Seattle Times. p. A4.

- Doughton, Sandi (March 24, 2014b). "River likely undercut slope, experts say". The Seattle Times. p. A5.

- "14 dead; 176 reports of people missing in mile-wide mudslide". The Seattle Times. March 24, 2014c. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- Armstrong, Ken; Carter, Mike; Baker, Mike (March 25, 2014a). "'Unforeseen' risk of slide? Warnings go back decades". The Seattle Times. pp. A1, A5.

- Baker, Mike; Armstrong, Ken; Bernton, Hal (March 25, 2014b). "State allowed logging on plateau above slope". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- Doughton, Sandi (March 25, 2014c). "Scientists say there's little chance tiny quake triggered slide". The Seattle Times.

- Baker, Mike; Mayo, Justin (March 26, 2014). "Logging OK'd in 2004 may have exceeded approved boundary". Seattle Times.

- Brunner, Jim; Berens, Michael J. (March 27, 2014). "County's own 2010 report called slide area dangerous". The Seattle Times. pp. A1, A7.

- Turnbull, Lornet; Sullivan, Jennifer (April 2, 2014). "Day 12: 'We are trying to be as honest as we can'". The Seattle Times. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- "Crews start work on berms to ease search for mudslide victims". The Seattle Times. April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- Brunner, Jim; Berens, Michael J. (April 9, 2014). "County's own 2010 report called slide area dangerous". Seattle Times.

- Sidle, Roy C.; Ochiai, Hirotaka (2006). Landslides: processes, prediction, and land use. Water Resources Monograph. Vol. 18. American Geophysical Union. ISBN 978-0-87590-322-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Snohomish County Medical Examiner’s Office (April 9, 2014). "Snohomish County Medical Examiner's Office Media Update". Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- Snohomish County Medical Examiner’s Office (April 1, 2014). 181 "Sunday night 530 landslide update".

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help)

- Snohomish County Sheriff's Office (April 9, 2014). 205 "SR 530 Slide Area Missing Person List". Retrieved April 9, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help)

- The Stranger: Kiley, Brendan (March 27, 2014). "Is There a Connection Between the Mudslide and Our State's Historical Mishmash of Logging Regulations?". SLOG. The Stranger. Seattle, Washington. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- Tabor, R. W.; Booth, D. B.; Vance, J. A.; Ford, A. B. (2002), "Geologic Map of the Sauk River 30- by 60- minute quadrangle, Washington", U.S. Geological Survey, Miscellaneous Investigations map I-2592, 2 sheets and pamphlet, scale 1:100,000.

- Washington Post: Berman, Mark (March 24, 2014). "Everything you need to know about the Washington landslide". Washington Post. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- Whidbey News Times: Reid, Janis (March 26, 2014). "Whidbey Island agencies assist in Oso mudslide response". Whidbey News Times.

Broken or incomplete references

- NETR Online (2006). "Fresh landslide tailings depicted in 2006 aerial photograph, with topology map comparisons". Historic Aerials. Nationwide Environmental Title Research, LLC.

- "Flash Flood Watch". National Weather Service. Retrieved March 27, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Forest Practices Board (November 2004), Q&A About Landslides and Geology, Washington State Department of Natural Resources, retrieved March 31, 2014

- "SR 530 Landslide". Washington State Department of Transportation. March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- "Obama declares major disaster for Oso landslide". kvue.com. KVUE Television. April 3, 2014. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- Christopher C. Burt (March 25, 2014). "Worst Landslides in U.S. History". Wunderground. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Snohomish County Official 530 Slide Updates (includes most recent lists of victims and missing people)

- The Seattle Times: Victims of the Oso mudslide (photos and brief bios of the people killed or missing)

- Oso mudslide victims (interactive aerial view of victims' addresses)

- USGS simulation shows how quickly the Washington landslide liquefied

- Washington mudslide: before and after (interactive aerial view of landslide area)

- Thorsen, 1967: Landslide of January 1967

- Tetra Tech Report, 2010, Ch. 14: Landslides

- Snohomish County Natural Hazard Mitigation Plan Update (presentation)

- Aerial History and LiDAR of the Stilliguamish Blocking Landslide

- Professor Cliff Mass, Cliff Mass Weather Blog: The Meteorological Background for the Stillaguamish Landslide

- Dr Dave Petley, The Landslide Blog