| Revision as of 00:29, 6 June 2014 editCrovata (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users6,846 edits →Etymology← Previous edit | Revision as of 01:36, 6 June 2014 edit undoCrovata (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users6,846 editsNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

| The origin of group of people called Morlachs, because of the etymology, are beleived originally to have been ], but as stated in work ''Travels in Dalmatia'' from 18th century by Fortis, they were speaking Slavic language, and because of migrations, people came from various parts of the Balkan, and the name passed to other communities. Those people were both of the ] and ] faith. | The origin of group of people called Morlachs, because of the etymology, are beleived originally to have been ], but as stated in work ''Travels in Dalmatia'' from 18th century by Fortis, they were speaking Slavic language, and because of migrations, people came from various parts of the Balkan, and the name passed to other communities. Those people were both of the ] and ] faith. | ||

| Fortis spotted the physical difference between Morlachs; those from around ], ] and ] generally were blond haired, with blue eyes, and broad face, while those around ] and ] generally brown haired and with narrow face. They also differed in nature. Although by the urban strangers were often seen as "those people" from periphery,<ref>{{Cite book| pages=126, 348| first=Larry| last=Wolff| publisher=Stanford University Press| year=2003| isbn=0-8047-3946-3| title=Venice and the Slavs: The Discovery of Dalmatia in the Age of Enlightenment|}} (With a specific reference to H.G. Wells' Morlocks, p. 348)</ref><ref>{{Cite journal| contribution=Morlachia| first=Richard| last=Brookes| publisher=F.C. and J. Rivington| year=1812| title=The general gazetteer or compendious geographical dictionary| page=501}}</ref> |

Fortis spotted the physical difference between Morlachs; those from around ], ] and ] generally were blond haired, with blue eyes, and broad face, while those around ] and ] generally brown haired and with narrow face. They also differed in nature. Although by the urban strangers were often seen as "those people" from periphery,<ref name="Wolff">{{Cite book| pages=126, 348| first=Larry| last=Wolff| publisher=Stanford University Press| year=2003| isbn=0-8047-3946-3| title=Venice and the Slavs: The Discovery of Dalmatia in the Age of Enlightenment|}} (With a specific reference to H.G. Wells' Morlocks, p. 348)</ref><ref>{{Cite journal| contribution=Morlachia| first=Richard| last=Brookes| publisher=F.C. and J. Rivington| year=1812| title=The general gazetteer or compendious geographical dictionary| page=501}}</ref> ] called them "barbarians" and "a race of ferocious men, unreasonable, without humanity, capable of any misdeed",<ref name="Wolff"/> while Fortis praised their "noble savagery", moral, family, and friendship virtues, but also complaint their persistent keeping to the old tradition. He found that they sang melancholic verses of epic poetry related to the Turkish occupation, accompanied with the traditional single stringed instrument called ]. They made their living as ] and merchants, as well soldiers. | ||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

Revision as of 01:36, 6 June 2014

Morlachs (Croatian and Template:Lang-sr, Serbian Cyrillic: Морлаци) was an ethnonym or exonym used for the rural population in the Lika and Dalmatian hinterlands (western Balkans in modern use) in the 14th and 18th centuries, usually connected with Vlachs.

Etymology

Ethnonym Morlach, is derived from the Italian term "Morlacoo", Latin term "Morlachus" (Murlachus), being cognate from Greek Μαυροβλάχοι (Mauroblakhoi), meaning "Black Vlachs" (from Greek mauro, dark or black). The Serbo-Croatian term in singular is Morlak and plural Morlaci or Морлаци. In Latin sources there are references to them also as "Nigri Latini". Petar Skok derived it from lat. maurus - gr. maurós (dark), which diphthongs au and av indicate to Dalmato-Romanian lexical remnant.

There are several interpretations of the ethnonym and phrase "moro/mavro/mauro vlasi". The direct translation of the name Morovlasi in Serbo-Croatian would mean Black Vlachs. It is considered that Black was referred to their clothes of brown cloth; The 17th century historian from Dalmatia Johannes Lucius, gave the thesis it actually meant "Black Latins" compared to "White Romans" in coastal areas; The 18th century writer Alberto Fortis in his book Travels in Dalmatia (1774), where extensively wrote about Morlachs, thought it came from Slavic language word "more" (sea), and morski Vlasi meaning "Sea Vlachs"; The same century writer Ivan Lovrić observing Fortis work thought it comes from "more" (sea) and "(v)lac(s)i" (strong) ("strongmen by the sea"), and mentioned how the Greeks called Upper Vlachia Maurovlachia thus Morlachs brought the name with them; There are also interpretations as "Northern Latins" (Cicerone Poghirc), deriving from the Turkish (Old-Indo European) practice of indicating cardinal directions by colors; As referrence to their camps and pastures which were built in "dark" places; It comes from Morea peninsula; from Morava river; or from African Maurs.

Origin and culture

The origin of group of people called Morlachs, because of the etymology, are beleived originally to have been Vlachs, but as stated in work Travels in Dalmatia from 18th century by Fortis, they were speaking Slavic language, and because of migrations, people came from various parts of the Balkan, and the name passed to other communities. Those people were both of the Greek-Orthodox and Roman Catholic faith.

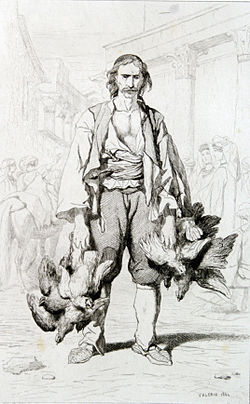

Fortis spotted the physical difference between Morlachs; those from around Kotor, Sinj and Knin generally were blond haired, with blue eyes, and broad face, while those around Zadvarje and Vrgorac generally brown haired and with narrow face. They also differed in nature. Although by the urban strangers were often seen as "those people" from periphery, Edward Gibbon called them "barbarians" and "a race of ferocious men, unreasonable, without humanity, capable of any misdeed", while Fortis praised their "noble savagery", moral, family, and friendship virtues, but also complaint their persistent keeping to the old tradition. He found that they sang melancholic verses of epic poetry related to the Turkish occupation, accompanied with the traditional single stringed instrument called gusle. They made their living as shepherds and merchants, as well soldiers.

History

Early history

The term Morlachs is first mentioned in the 14th century. In 1344, are mentioned Morolacorum in lands around Knin and Krbava, within the conflict of counts from Kurjaković and Nelipić families. In 1352, in the agreement in which Zadar sold salt to the Republic of Venice, in which Zadar retained part of the salt that Morlachi and others exported by land. In 1362, Morlachorum, when for few months unauthorized settled on lands of Trogir and used it for pasture. In the Statute of Senj from 1388 by Frankopan family, are mentioned Morowlachi, in which is defined the amount of time they have for pasture when descend from the mountains. In 1412, Murlachos, when captured the Ostrovica Fortress from Venice.

In the old Croatian documents, Morlachs were equaled to Vlach shepherds. There were two groups of Vlachs in documents in Croatia. One group was the regular Vlachs who lived in Lika, while the others were actual Morlachs, called so in Venice and Italian documents, who lived between Senj and Zadar. Those Vlachs by the end of 14th and 15th century lost, if spoke, their Romanian language, or were at least bilingual. As they adopted Slavic language, the only charateristic "Vlach" element was pastoral way of life. Some groups continued to speak Romanian language, as seen by their descendents on the island of Krk and villages around the Čepić lake in Istria.

In the 15th century, those groups of Vlachs, possibly of Morlachs, were invited to settle into the Istrian Peninsula (throughout, and mountain Ćićarija) after the various devastating outbreaks of the plague and war between 1400–1600, and reached the island of Krk.

16th century

As many former inhabitants of the Croatian-Ottoman borderland fled northwards or were captured by the Ottoman invaders, they left unpopulated areas. At the time, Vlachs, served both in Ottoman armies during their conquests, those of local nobility, Austria and Venice, and were settled by both sides. This migrations inicially weren't considerablly large, but after the Christian-Muslim war of 1593 - 1606, Vlachs began arriving in Croatia en masse. The Austrian Empire established the Military Frontiers in 1522, which served as a buffer against Ottoman incursions.

From this century, the previous association of the term with autochthonous people starts to lose. In most documents by Venice, Morlachs are usually called immigrants (initially of both Catholic and Orthodox faith) from conquested territory previously of Croatian and Bosnian kingdoms by Ottoman Empire, who settled in inland of the coastal cities, enterted the military service, and before the half of 17th century lived on Venice-Ottoman border.

The name "Morlach" expanded also to geographical terms, the mountain Velebit was called Montagne della Morlacca (Morlach Mountain), lands below Morlachia, and Velebits canal the Canale della Morlacca.

17th century

In the 17th-century, at the time of Cretan War (1645–69) and Morean War (1684-99) was settled the biggest number of Morlachs, mostly inland of cities and Ravni Kotari of Zadar. They were skilled in warfare and familiar with local territory, and served as paid soldiers in both Venice and Ottoman armies. Their activity was simultaneous with those of Uskoks. Military service granted them lands, freed from usual trials, and gave them rights which freed from full debt (only 1/10 yield) law, thus many joined the "Morlachs" or "Vlachs" armies. At the time, some notable head leaders of Morlachs, who were also sung in epic poetry, are Janko Mitrović, Ilija and Stojan Janković, Ilija, Franjo and Petar Smiljanić, Stjepan and Marko Sorić, Vuk Mandušić, Šimun Bortulačić, Božo Milković, Stanko Sočivica, Ilija Peraica, and counts Franjo and Juraj Posedarski. As Morlachs were of both Ortodox and Catholic faith, roughly, Mitrović-Janković family were the leaders of Ortodox, while Smiljanić family of Catholic Morlachs.

After the dissolution of Republic of Venice in 1797, and loss of power in Dalmatia, the term Morlach would steadly dissappear from use. Although in some historical documents were referred as a nation, it can't be told it was, or that the name belonged to only one ethnic group, ie. Vlachs who didn't manage to make a national identity, or later Croatian or Serbian, yet according to the religious affiliation, they assimilated to these two ethnic groups.

Legacy

According to the 1991 Croatian census, 22 people declared themselves as Morlachs. There was no data on Morlachs in the 2001 Croatian census.

See also

Annotations

- The linguistic assimilation didn't entirely erased Romanian words, the evidence are toponims, and anthroponyms (personal names) with specific Romanian or Slavic words roots, and surname ending suffixes "-ul", "-ol", "-at", "-ar", "-as", "-an", "-et", "-ez", after Slavicization often accompanied with ending suffixes "-ić", "-vić", "-ović".

- That the pastoral way of life was specific for Vlachs is seen in the third chapter of eight book in Alexiad, 12th century work by Anna Komnene, where along Bulgars are mentioned tribes who live a nomadic life usually called Vlachs. In this and many other older Medieval documents, the term was often mentioned along other ethnic names, thus being more an ethnic than just a social-professional category. Although included both of them, P. S. Nasturel emphasized there existed other general expressions for pastors.

- "Vlachs", referring to pastoralists, since 16th century was a common name for Serbs in the Ottoman Empire and later. Tihomir Đorđević points to the already known fact that the name 'Vlach' didn't only refer to genuine Vlachs or Serbs but also to cattle breeders in general. Serbian documents from the 12th to 14th century mention Vlachs separately from Serbs, for example the prohibition of intermarriage between Serbs and Vlachs by Emperor Dušan the Mighty. A letter of Emperor Ferdinand, sent on November 6, 1538, to Croatian ban Petar Keglević, in which he wrote "Captains and dukes of the Rasians, or the Serbs, or the Vlachs, who usually call themselves the Serbs". In the work "About the Vlachs" from 1806, Metropolitan Stevan Stratimirović states that Roman Catholics from Croatia and Slavonia scornfully used the name 'Vlach' for "the Slovenians (Slavs) and Serbs, who are of our, Eastern confession (Orthodoxy)", and that "the Turks in Bosnia and Serbia also call every Bosnian or Serbian Christian a Vlach" (T. Đorđević, 1984:110) However, the immigrants, irrelevant of religion, and especially of nationality which didn't exist until the 19th century, who took refuge in the Military Frontier and inland of coastal cities, were called "Vlachs" or "Morlachs".

- The head leaders in Venice, Ottoman and local Slavic documents were titled as capo, capo direttore, capo principale de Morlachi (J. Mitrović), governatnor delli Morlachi (S. Sorić), governator principale (I. Smiljanić), gospodin serdar s vojvodami or lo dichiariamo serdar; serdar, and harambaša.

References

- Ivan Mužić (2011). Hrvatska kronika u Ljetopisu pop Dukljanina (PDF). Split: Muzej hrvatski arheoloških spomenika. p. 66 (Crni Latini), 260 (qui illo tempore Romani vocabantur, modo vero Moroulachi, hoc est Nigri Latini vocantur.).

In some Croatian and Latin redactions of the Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja, from 16th century.

- P. Skok (1972). Etymological dictionary of Croatian or Serbian language. Vol. II. Zagreb: JAZU. p. 392-393.

- P. S. Nasturel (1979). Les Valaques balcaniques aux Xe-XIIIe siècles (Mouvements de population et colonisation dans la Romanie grecque et latine). Vol. Byzantinische Forschungen VII. Amsterdam. p. 97.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Zef Mirdita (2001). Tko su Maurovlasi odnosno Nigri Latini u "Ljetopisu popa Dukljanina". Vol. 47. Zagreb: Croatica Christiana periodica. p. 17-27.

- Cicerone Poghirc (1989). Romanisation linguis tique et culturelle dans les Balkans. Survivance et évolution, u: Les Aroumains... Paris: INALCO. p. 23.

{{cite book}}: soft hyphen character in|title=at position 21 (help) - ^ "I Vlasi o Morlacchi, i latini delle alpi dinariche" (in Italian). ilbenandante. Retrieved 2. 09. 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Vladimir Mažuranić (1908–1922). Prinosi za hrvatski pravno-povjestni rječnik. Zagreb: JAZU. p. 682.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - Dominik Mandić (1956). Postanak Vlaha prema novim poviestnim istraživanjima. Vol. 18–19. Buenos Aires: Hrvatska misao. p. 35.

- ^ Wolff, Larry (2003). Venice and the Slavs: The Discovery of Dalmatia in the Age of Enlightenment. Stanford University Press. pp. 126, 348. ISBN 0-8047-3946-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) (With a specific reference to H.G. Wells' Morlocks, p. 348) - Brookes, Richard (1812). "The general gazetteer or compendious geographical dictionary". F.C. and J. Rivington: 501.

{{cite journal}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Mužić 2010, p. 10, 11: Et insuper mittemus specialem nuntium…. Gregorio condam Curiaci Corbavie,…. pro bono et conservatione dicte domine (Vedislave) et comitis Johannis,….; nec non pro restitutione Morolacorum, qui sibi dicuntur detineri per comitem Gregorium…; Exponat quoque idem noster nuncius Gregorio comiti predicto quod intelleximus, quod contra voluntatem ipsius comitis Johannis nepotis sui detinet catunos duos Morolacorum…. Quare dilectionem suam… reget, quatenus si quos Morolacos ipsius habet, placeat illos sibi plenarie restitui facere…

- Listine o odnošajih Južnoga Slavenstva i Mletačke Republike. Vol. III. Zagreb: JAZU. 1872. p. 237.

Prvi se put spominje ime »Morlak« (Morlachi) 1352 godine, 24. lipnja, u pogodbi po kojoj zadarsko vijeće prodaje sol Veneciji, gdje Zadar zadržava dio soli koju Morlaci i drugi izvoze, kopnenim putem.

- Mužić 2010, p. 11: Detractis modiis XII. milie salis predicti quolibet anno que remaneant in Jadra pro usu Jadre et districtu, et pro exportatione solita fi eri per Morlachos et alios per terram tantum…

- Mužić 2010, p. 12: quedam particula gentis Morlachorum ipsius domini nostri regis... tentoria (tents), animalia seu pecudes (sheep)... ut ipsam particulam gentis Morlachorum de ipsorum territorio repellere… dignaremur (to be repelled from city territory)... quamplures Morlachos... usque ad festum S. Georgii martiris (was allowed to stay until April 24, 1362).

- L. Margetić (2007). Statute of Senj from 1388 (in Latin and Croatian). Vol. 34, No. 1, December. Senj: Senjski Zbornik. p. 63, 77.

§ 161. Item, quod quando Morowlachi exeunt de monte et uadunt uersus gaccham, debent stare per dies duos et totidem noctes super pascuis Senie, et totidem tempore quando reuertuntur ad montem; et si plus stant, incidunt ad penam quingentarum librarum.

- Mužić 2010, p. 13: Cum rectores Jadre scripserint nostro dominio, quod castrum Ostrovich, quod emimusa Sandalo furatum et acceptum sit per certos Murlachos, quod non est sine infamia nostri dominii...

- Mužić 2010, p. 21.

- ^ Mužić 2010, p. 73: "As evidence Vlachs spoke a variation of Romanian language, Mužić later in the paragraph referred to the Istro-Romanians, and Dalmatian language on island Krk." Cite error: The named reference "FOOTNOTEMužić201073" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- P. Šimunović (2009). Uvod U Hrvatsko Imenoslovlje (in Croatian). Zagreb: Golden marketing-Tehnička knjiga. p. 53, 123, 147, 150, 170, 216, 217.

- Božidar Ručević (2011-02-27). "Vlasi u nama svima" (in Croatian). Rodoslovlje.

- Mužić 2010, p. 80.

- ^ Zef Mirdita (1995). Balkanski Vlasi u svijetlu podataka Bizantskih autora (in Croatian). Zagreb: Croatian History Institute. p. 65, 66.

- ^ D. Gavrilović (2003). "Elements of ethnic identification of the Serbs" (Document). Niš.

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - Zef Mirdita (2004). Vlasi u historiografiji. Zagreb: Croatian History Institute.

- Noel Malcolm (1999). Kosovo, A short History. New York: University Press.

- Suppan & Graf 2010, p. 59.

- ^ Croatian Encyclopaedia (2011). "Morlaci" (in Croatian).

- Milan Ivanišević (2009). Izvori za prva desetljeća novoga Vranjica i Solina (in Croatian). Vol. 2, No. 1 September. Solin: Tusculum. p. 98.

- ^ Boško Desnica (1950–1951). Istorija Kotarski Uskoka 1646-1749 (PDF) (in Serbian). Vol. I–II. Venice: SANU. p. 140, 141, 142.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - Ivan Lovrić. Osservazioni sopra diversi pezzi del Viaggio in Dalmazia del signor abate Alberto Fortis coll'aggiunta della Vita di Soçivizça (in Italian). Venice. p. 223.

- Drago Roksandić (2003). Triplex Confinium, Ili O Granicama I Regijama Hrvatske Povijesti 1500-1800 (PDF) (in Croatian). Zagreb: Barbat. p. 140, 141, 169.

- Croatian 2001 census, detailed classification by nationality

Sources

- John Van Antwerp Fine (2006). When ethnicity did not matter in the Balkans. ISBN 0472025600.

- Norman M. Naimark; Holly Case (2003). Yugoslavia and Its Historians: Understanding the Balkan Wars of the 1990s. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4594-9.

- Suppan, Arnold; Graf, Maximilian (2010). From the Austrian Empire to the Communist East Central Europe. Lit Verlag. ISBN 978-3-643-50235-3.

- Mužić, Ivan (2010). Vlasi u starijoj hrvatskoj historiografiji (PDF) (in Croatian). Split: Muzej hrvatskih arheoloških spomenika. ISBN 978-953-6803-25-5.

External links

- Croatian Encyclopaedia (2011). "Morlaci".