| Revision as of 17:17, 15 June 2014 editCOD T 3 (talk | contribs)617 edits Undid revision 613026444 by Faustian (talk) Edit Warring: this statement does not say the Blue Army or Haller's troops specifically committed rape, please stop reading disputed text.← Previous edit | Revision as of 09:55, 26 June 2014 edit undoR'n'B (talk | contribs)Administrators420,984 editsm Disambiguating links to Galicia (link changed to Galicia (Eastern Europe)) using DisamAssist.Next edit → | ||

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

| Although Poles hold the Blue Army in high regard for its successful effort in stopping the ] advance into ] and securing Poland's unstable eastern border, many ethnic ] and ] generally see its conduct during the war in a negative light.<ref name="Prusin 2005 pg. 103">{{cite book |author=Alexander Victor Prusin |title=Nationalizing a Borderland: War, Ethnicity, and Anti-Jewish Violence in East Galicia, 1914-1920 |url=http://books.google.ca/books?id=jb5tAAAAMAAJ&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=Haller |year=2005 |location=Tuscaloosa, AL |publisher=University of Alabama Press |isbn=0817314598 |page=103 |quote=''Note:'' the exact phrase 'Blue Army' is inside this book. It refers to it as Haller's Army}}</ref> Hostility exhibited by some of the soldiers, directly stemmed from earlier events of the ], when Poles rose up against German rule, only to find out that the Jews in the region sided with the German authorities; a decision primarily based on economic factors.<ref name="Prusin 2005 pg. 103"/> As a result, Jews perceived Haller's Army as particularly harmful to their interests.<ref name="bare_url"/><ref name="HeikoHaumann"/><ref name="web"/> The soldiers and officers targeted local Jewish, and Ukrainian civilians believed that they were acting in Poland's defense, assuming that the victims were collaborating with their enemies; either the ], or Bolshevik Russia.<ref name="threatening"/> But, many of the civilians targeted were not hostile to the Polish military in any way.<ref name="binghamton"/> Some of the more significant incident of abuse occurred from within the ranks of the Polish-American volunteers. It is likely that the cultural shock of finding themselves confronted by a multitude of unfamiliar ethnic, political, and religious groups that inhabited Western Ukraine led to a feeling of vulnerability, that in turn provoked the violent outbursts.<ref name="Eichenberg"/> | Although Poles hold the Blue Army in high regard for its successful effort in stopping the ] advance into ] and securing Poland's unstable eastern border, many ethnic ] and ] generally see its conduct during the war in a negative light.<ref name="Prusin 2005 pg. 103">{{cite book |author=Alexander Victor Prusin |title=Nationalizing a Borderland: War, Ethnicity, and Anti-Jewish Violence in East Galicia, 1914-1920 |url=http://books.google.ca/books?id=jb5tAAAAMAAJ&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=Haller |year=2005 |location=Tuscaloosa, AL |publisher=University of Alabama Press |isbn=0817314598 |page=103 |quote=''Note:'' the exact phrase 'Blue Army' is inside this book. It refers to it as Haller's Army}}</ref> Hostility exhibited by some of the soldiers, directly stemmed from earlier events of the ], when Poles rose up against German rule, only to find out that the Jews in the region sided with the German authorities; a decision primarily based on economic factors.<ref name="Prusin 2005 pg. 103"/> As a result, Jews perceived Haller's Army as particularly harmful to their interests.<ref name="bare_url"/><ref name="HeikoHaumann"/><ref name="web"/> The soldiers and officers targeted local Jewish, and Ukrainian civilians believed that they were acting in Poland's defense, assuming that the victims were collaborating with their enemies; either the ], or Bolshevik Russia.<ref name="threatening"/> But, many of the civilians targeted were not hostile to the Polish military in any way.<ref name="binghamton"/> Some of the more significant incident of abuse occurred from within the ranks of the Polish-American volunteers. It is likely that the cultural shock of finding themselves confronted by a multitude of unfamiliar ethnic, political, and religious groups that inhabited Western Ukraine led to a feeling of vulnerability, that in turn provoked the violent outbursts.<ref name="Eichenberg"/> | ||

| After arriving in ], individual soldiers engaged in acts of violence against the local Jewish populations.<ref name="international"/> In ] on 27 May 1919, a soldier by the name of Stanislaw Dziadecki who served in one of the Blue Army's rifle divisions, was shot while on patrol, in an apparent sniper attack; a local Jewish tailor, who sympathized with the Bolshevik cause was suspected of committing the attack.<ref name="Wakounig2012">{{cite book|author=Marija Wakounig|title=From Collective Memories to Intercultural Exchanges|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=5e5w8T1DNWwC&pg=PA196|date=28 November 2012|publisher=LIT Verlag Münster|isbn=978-3-643-90287-0|page=196}}</ref> In an effort to apprehend the suspect, Haller's troops aided by local Polish civilians conducted a three hour assault on the town's Jewish quarter that left 5 Jews dead and 45 wounded.<ref name="Carole Finke 2006 pg. 230">Carole Finke. (2006). Defending the Rights of Others The Great Powers, the Jews, and International Minority Protection, 1878–1938. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pg. 230</ref> As the army traveled further east, some of Haller's soldiers as a way to exact retribution looted Jewish houses, pushed local Jews off moving trains,<ref name="bare_url"/>{{Dubious|date=June 2014}} and with their bayonets cut off the beards of Orthodox Jews. Haller's troops, along with the Poznań regiments, committed ] in ], the area around ], and Grodek Jagiellonski.<ref name="Prusin 2005 pg. 103"/> where local Jews openly sided with the Ukrainians; Jewish civic committees actively recruited able-bodied men to fight in the ], and Jewish youth served as scouts for the Ukrainian military.<ref name="Alexander Victor Prusin 2005 pg. 100">Alexander Victor Prusin (2005). ''Nationalizing a Borderland: War, Ethnicity, and Anti-Jewish Violence in East Galicia, 1914-1920''. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, pg. 100."</ref> | After arriving in ], individual soldiers engaged in acts of violence against the local Jewish populations.<ref name="international"/> In ] on 27 May 1919, a soldier by the name of Stanislaw Dziadecki who served in one of the Blue Army's rifle divisions, was shot while on patrol, in an apparent sniper attack; a local Jewish tailor, who sympathized with the Bolshevik cause was suspected of committing the attack.<ref name="Wakounig2012">{{cite book|author=Marija Wakounig|title=From Collective Memories to Intercultural Exchanges|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=5e5w8T1DNWwC&pg=PA196|date=28 November 2012|publisher=LIT Verlag Münster|isbn=978-3-643-90287-0|page=196}}</ref> In an effort to apprehend the suspect, Haller's troops aided by local Polish civilians conducted a three hour assault on the town's Jewish quarter that left 5 Jews dead and 45 wounded.<ref name="Carole Finke 2006 pg. 230">Carole Finke. (2006). Defending the Rights of Others The Great Powers, the Jews, and International Minority Protection, 1878–1938. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pg. 230</ref> As the army traveled further east, some of Haller's soldiers as a way to exact retribution looted Jewish houses, pushed local Jews off moving trains,<ref name="bare_url"/>{{Dubious|date=June 2014}} and with their bayonets cut off the beards of Orthodox Jews. Haller's troops, along with the Poznań regiments, committed ] in ], the area around ], and Grodek Jagiellonski.<ref name="Prusin 2005 pg. 103"/> where local Jews openly sided with the Ukrainians; Jewish civic committees actively recruited able-bodied men to fight in the ], and Jewish youth served as scouts for the Ukrainian military.<ref name="Alexander Victor Prusin 2005 pg. 100">Alexander Victor Prusin (2005). ''Nationalizing a Borderland: War, Ethnicity, and Anti-Jewish Violence in East Galicia, 1914-1920''. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, pg. 100."</ref> | ||

| In an effort to curb the abuses, General Józef Haller himself issued a proclamation demanding that his soldiers stop cutting off beards of Orthodox Jews.<ref name="publication"/> Also, in due course the individual soldiers involved in confirmed acts of antisemitism did receive punishment for their abusive actions. To counter some of the false or exaggerated claims of antisemitism that were reported by the press, Polish Government officials, supported by their French allies, noted that many of the alleged antisemitic tracts attributed to the Blue Army were in fact a product of willful disinformation based purely on hearsay and confabulation emanating from Russian and German government sources in an effort to discredit the new Polish Government, and in the process weaken the much needed Allied support for the new Polish State.<ref name="international"/> The overall scale of the violence was estimated at around 400 to 500 Jewish casualties, and historian ] characterized Jewish losses as being minimal in comparison to Poles and Ukrainians killed during the war.<ref>Howard M. Sachar. (2007). ''Dreamland: Europeans and Jews in the Aftermath of the Great War'', Random House LLC: page 25.</ref><ref>Tadeusz Piotrowski. (1998). ''Poland's Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918-1947'', McFarland: page 43.</ref> | In an effort to curb the abuses, General Józef Haller himself issued a proclamation demanding that his soldiers stop cutting off beards of Orthodox Jews.<ref name="publication"/> Also, in due course the individual soldiers involved in confirmed acts of antisemitism did receive punishment for their abusive actions. To counter some of the false or exaggerated claims of antisemitism that were reported by the press, Polish Government officials, supported by their French allies, noted that many of the alleged antisemitic tracts attributed to the Blue Army were in fact a product of willful disinformation based purely on hearsay and confabulation emanating from Russian and German government sources in an effort to discredit the new Polish Government, and in the process weaken the much needed Allied support for the new Polish State.<ref name="international"/> The overall scale of the violence was estimated at around 400 to 500 Jewish casualties, and historian ] characterized Jewish losses as being minimal in comparison to Poles and Ukrainians killed during the war.<ref>Howard M. Sachar. (2007). ''Dreamland: Europeans and Jews in the Aftermath of the Great War'', Random House LLC: page 25.</ref><ref>Tadeusz Piotrowski. (1998). ''Poland's Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918-1947'', McFarland: page 43.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 09:55, 26 June 2014

For other uses, see Blue Army (disambiguation).| Blue Army or Haller's Army | |

|---|---|

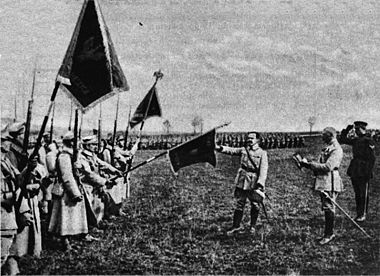

Blue Army troops and General Józef Haller, c.1918 Blue Army troops and General Józef Haller, c.1918 | |

| Active | 1917 - 1921 |

| Country | |

| Branch | Polish Legions |

| Size | 68,500 |

| Engagements | World War I, Polish–Ukrainian War, Polish–Soviet War |

| Commanders | |

| General | Józef Haller de Hallenburg |

The Blue Army (Polish: Błękitna Armia), or Haller's Army was a Polish military contingent created in France during the latter stages of World War I. The name comes from the blue army uniforms worn by the soldiers; the symbolic term used to describe the troops, was then subsequently adopted by General Józef Haller de Hallenburg, to represent all newly formed Polish Legions, fighting in western Europe.

The army was formed on 4 June 1917, composed of Polish volunteers serving alongside the allied forces in France. After fighting on the Western Front during World War I, the army was transferred to Poland; where it joined other Polish military formations battling in the east. During the Polish-Ukrainian War, the Blue Army helped to break a stalemate in Poland's favor; and during the Polish-Bolshevik War, Haller's troops played a critical role in the country's successful defense against the advancing Bolshevik forces.

During the fighting on the Ukrainian front, elements of the Blue Army were involved in antisemitic violence, where political Jewish organizations found themselves sharing ideological platforms with Bolshevik Russia, as well as communist elements in Western Ukraine, and post-war revolutionary Germany.

History

Background

The emergence of the Blue Army was closely associated with the American entry into World War I in April 1917. A month earlier Ignacy Paderewski submitted a proposal in the House to accept Polish-American volunteers for service on the Western Front in the name of Poland's independence. Some 24,000 Poles were taken in (out of 38,000 who applied) and after a brief military training, they were sent to France to join General Haller, including many women volunteers (PSK). Polish-Americans were eager to fight for freedom and the American-style democracy because they themselves escaped persecution by the empires who partitioned Poland a century earlier. When the war erupted, the American Polonia created the Polish Central Relief Committee to help with the war effort, although ethnically Polish volunteers arrived in France from all Polish diasporas at the same time numbering over 90,000 soldiers eventually. The Entente responded in kind by recognizing the Polish National Committee formed in France (led by Dmowski) as Poland's interim government, with the Wilson's written promise (issued on 8 January 1918) to recreate sovereign Polish state after their victory. Poland's long-term occupier, the Tsarist Russia, got out of the war as first, overrun by the Bolsheviks who signed a treaty in Brest-Litovsk on 3 March 1918. The imperial Germany surrendered in the 11 November 1918 armistice.

The Blue Army was formally merged into the Polish Army after the Armistice between the Allies and Germany. Meanwhile, three interim Polish governments emerged independently of each other. A socialist government led by Daszyński was formed in Lublin. The National Committee emerged in Kraków. Daszyński (lacking support) decided to join forces with Piłsudski who was just released by the Germans from Magdeburg. On 16 November 1918 Poland declared independence. A decree defining the new republic was issued in Warsaw on 22 November 1918. A month later Paderewski joined in from France. At about the same time, heavily armed Ukrainians from the Sitchovi Stril'ci (Sitch Riflemen) seized the city of Lwów, and the battle for the control of the city erupted against the Piłsudski's legionaries. It was a high stakes gamble with all sides attempting to set a new reality on the ground ahead of the European peace conference in Versailles of January 1919. Similar Polish uprisings erupted in Poznań (27 December 1918) and in Upper Silesia in August 1919 and 1920, and in May 1921, separated by the ad-hoc (or outright illegitimate) plebiscites with trainloads of German agents acting as local inhabitants. In the spring of 1919 the Blue Army (no longer needed in the West) was transported to Poland by train. The German forces were very slow to withdraw. In all, some 2,100 soldiers of the Blue Army who enlisted in France from the Polish diasporas died in the fighting including over 50 officers serving with Haller. Over 1,600 men were wounded. The Haller's army included 25,000 ethnic Poles drafted against their will by the German and Austrian armies, out of 50,000 conscripts from across the partitioned Poland. They joined Haller from the POW camps in Italy in 1919. The final borders of Poland were set only in October 1921 by the League of Nations.

Western Front

The first divisions were formed after the official signing of a 1917 alliance by French President Raymond Poincaré and the Polish statesman Ignacy Jan Paderewski. The majority of the recruits, approximately 35,000 of them were either Poles serving in the French Army, or former captured Polish prisoners of war; who were conscripted, and forced to serve in the Deutsches Heer and Imperial-Royal Landwehr armies. Many other Poles also joined, from all over the world—these units included recruits from the United States, with an additional 23,000 Polish-American volunteers, and former troops of the Russian Expeditionary Force in France. Also, Polish diaspora form Brazil joined the army, with more than 300 men volunteering to take up the cause.

The Blue Army was initially placed under direct French military control, and commanded by General Louis Archinard. However, on 23 February 1918 political and military sovereignty was granted to the Polish National Committee, and soon thereafter the army was directly commanded by independent Polish authorities. Also, it was during this time that more units were formed; most notably the 4th and 5th Rifle Divisions in Russia. On 28 September, Russian government officials formally signed an agreement with the Entente, that officially recognized the Polish military units in France as "the only independent, allied, and co-belligerent Polish army". On 4 October 1918, the National Committee appointed General Józef Haller de Hallenburg as chief commander of the Polish Legions in France.

The first unit to enter combat on the Western Front was the 1st Rifle Regiment (1 Pułk Strzelców Polskich), fighting from July 1918 in Champagne and the Vosges mountains. By October the entire 1st Rifle Division had joined the campaign around the area of Rambervillers and Raon-l'Étape.

Transfer to Poland

The army continued to gather new recruits after the end of World War I. Many of these new volunteers were ethnic Poles who were conscripted into the German, Austrian and Russian armies, and later discharged following the signing of the armistice agreement, on 11 November 1918 . By early 1919 the Blue Army numbered 68,500 men, and was fully equipped by the French government. After being denied permission by German officials to enter Poland via the Baltic port city of Danzig (Gdańsk), transportation was arranged via train. Between April and June of that year, all the army units were moved together to a newly independent Poland, across Germany in sealed train cars. Weapons were secured in separate compartments and kept under guard; to appease German concerns about a foreign army traversing its territory. Immediately after its arrival, the divisions were integrated into the regular Polish Army, and sent to the front lines to fight in the Polish-Ukrainian War; which was being fought in eastern Galicia.

The perilous journey from France, through revolutionary Germany, into Poland, in the spring of 1919 has been documented by those who lived through it.

Captain Stanislaw I. Nastal: Preparations for the departure lasted for some time. The question of transit became a difficult and complicated problem. Finally after a long wait a decision was made and officially agreed upon between the Allies and Germany.

The first transports with the Blue Army set out in the first half of April 1919. Train after train tore along though Germany to the homeland, to Poland.

Major Stefan Wyczolkowski: On 15 April 1919 the regiment began its trip to Poland from the Bayon railroad station in four transports, via Mainz, Erfurt, Leipzig, Kalisz, and Warsaw, and arrived in Poland, where it was quartered in individual battalions; in Chełm 1st Battalion, supernumerary company and command of the regiment; 3rd Battalion in Kowel; and the 2nd Battalion in Wlodzimierz.

Major Stanislaw Bobrowski: On 13 April 1919 the regiment set out across Germany for Poland, to reinforce other units of the Polish army being created in the homeland amid battle, shielding with their youthful breasts the resurrected Poland.

Major Jerzy Dabrowski: Finally on 18 April 1919 the regiment’s first transport set out for Poland. On 23 April 1919 the leading divisions of the 3rd Regiment of Polish Riflemen set foot on Polish soil, now free thanks to their own efforts.

Lt. Wincenty Skarzynski: Weeks passed. April 1919 arrived – then plans were changed: it was decided irrevocably to transport our army to Gdańsk instead by trains, through Germany. Many officers came from Poland, among them Major Gorecki, to coordinate technical details with General Haller.

After World War I

Haller's troops changed the balance of power in Galicia and Volhynia. Their arrival allowed the Poles to repel the Ukrainians, and establish a demarcation line at the river Zbruch on 14 May 1919. The Blue Army was well equipped by the Western Allies, and augmented with experienced French officers specifically ordered to fight against the Bolsheviks; but not the forces of the Western Ukrainian People's Republic. Despite the diplomatic conditions, the Poles dispatched Haller's Army against the Ukrainians first, instead of the Bolsheviks; this was done in order to break the stalemate in eastern Galicia. In response, the allies sent several telegrams ordering the Polish government to halt its offensive; as using the allied-equipped army against the Western Ukrainian People's Republic specifically contradicted the status of the French military advisors, but subsequently these demands were ignored, with Poles remarking that "all Ukrainians were Bolsheviks".

In July 1919 the Blue Army was transferred to the border with Germany in Silesia, where it prepared defences against a possible German invasion of Poland, from the west.

Haller's well trained and highly motivated troops—as well, as their British build Bristol F.2 reconnaissance planes and Italian made Ansaldo A.1 Balilla fighters; along with the excellent French FT-17 tanks—formed the core of Poland's armed forces during the ensuing Polish-Bolshevik War, and turned the tide of the battle in favor of Poland.

Postwar

The 15th Infantry Rifle Regiment of the Blue Army was the basis for the 49th Hutsul Rifle Regiment of the 11th Infantry Division.

As with most of the history related to the Polish-Soviet War, information on the Blue Army was censored, distorted, and repressed by the Soviet authorities during the communist oppression of Poland, following the years after World War II.

Controversies

Civilian casualties

| This section may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. Please help improve it by rewriting it in a balanced fashion that contextualizes different points of view. (June 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Although Poles hold the Blue Army in high regard for its successful effort in stopping the Bolshevik advance into Central Europe and securing Poland's unstable eastern border, many ethnic Ukrainians and Jews generally see its conduct during the war in a negative light. Hostility exhibited by some of the soldiers, directly stemmed from earlier events of the Greater Poland Uprising, when Poles rose up against German rule, only to find out that the Jews in the region sided with the German authorities; a decision primarily based on economic factors. As a result, Jews perceived Haller's Army as particularly harmful to their interests. The soldiers and officers targeted local Jewish, and Ukrainian civilians believed that they were acting in Poland's defense, assuming that the victims were collaborating with their enemies; either the Ukrainian Galician Army, or Bolshevik Russia. But, many of the civilians targeted were not hostile to the Polish military in any way. Some of the more significant incident of abuse occurred from within the ranks of the Polish-American volunteers. It is likely that the cultural shock of finding themselves confronted by a multitude of unfamiliar ethnic, political, and religious groups that inhabited Western Ukraine led to a feeling of vulnerability, that in turn provoked the violent outbursts.

After arriving in Galicia, individual soldiers engaged in acts of violence against the local Jewish populations. In Częstochowa on 27 May 1919, a soldier by the name of Stanislaw Dziadecki who served in one of the Blue Army's rifle divisions, was shot while on patrol, in an apparent sniper attack; a local Jewish tailor, who sympathized with the Bolshevik cause was suspected of committing the attack. In an effort to apprehend the suspect, Haller's troops aided by local Polish civilians conducted a three hour assault on the town's Jewish quarter that left 5 Jews dead and 45 wounded. As the army traveled further east, some of Haller's soldiers as a way to exact retribution looted Jewish houses, pushed local Jews off moving trains, and with their bayonets cut off the beards of Orthodox Jews. Haller's troops, along with the Poznań regiments, committed pogroms in Sambir, the area around Lviv, and Grodek Jagiellonski. where local Jews openly sided with the Ukrainians; Jewish civic committees actively recruited able-bodied men to fight in the Ukrainian Galician Army, and Jewish youth served as scouts for the Ukrainian military.

In an effort to curb the abuses, General Józef Haller himself issued a proclamation demanding that his soldiers stop cutting off beards of Orthodox Jews. Also, in due course the individual soldiers involved in confirmed acts of antisemitism did receive punishment for their abusive actions. To counter some of the false or exaggerated claims of antisemitism that were reported by the press, Polish Government officials, supported by their French allies, noted that many of the alleged antisemitic tracts attributed to the Blue Army were in fact a product of willful disinformation based purely on hearsay and confabulation emanating from Russian and German government sources in an effort to discredit the new Polish Government, and in the process weaken the much needed Allied support for the new Polish State. The overall scale of the violence was estimated at around 400 to 500 Jewish casualties, and historian Norman Davies characterized Jewish losses as being minimal in comparison to Poles and Ukrainians killed during the war.

As a result of the Blue Army's activities Haller's visit to the United States was met with protests from American Jewish and Ukrainian communities.

Wrongful accusations

| This section possibly contains original research. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (June 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The Blue Army was wrongly accused of committing pogroms in Lviv by historian William W. Hagen, and Lida. But, the army's participation was impossible, since according to the Cambridge History of Poland, when the Lviv and Lida pogroms actually took place the Blue Army was still in France fighting on the Western Front. Also, it has been documented that the first units did not reach Poland until the spring of 1919, nearly five months after the Lviv pogrom occurred. The Kronika Polski lists 14 April 1919 as the start of the first transports form France to Poland, and historian Kay Lundgreen-Nielsen stated that the first units of the army did not leave France until 15 April 1919; its departure having been delayed by opposition from Britain and the United States. Thus, requiring a special protocol before the Blue Army was allowed to return home to Poland.

Personnel

Jewish volunteers

Despite examples of antisemitic behavior exhibited by some troops within the Blue Army, thousands of Polish Jews enlisted and fought within its ranks, and served as doctors and nurses. Some even received an officer's commission and took up leadership positions. Jews serving in the Blue Army's 43rd Regiment of Eastern Frontier Riflemen were listed as combat fatalities, and historian Edward Goldstein has identified approximately five percent of the unit's battle casualties as having a Jewish background.

Veteran status of Polish-American volunteers

After the war, the Polish-American volunteers who served within Haller's Army were not recognized as veterans by either the American or Polish governments. This led to friction between the Polish community in the United States and the Polish government, and resulted in the subsequent refusal by Polish-Americans to again help the Polish cause militarily.

Order of battle

- I Polish Corps

- 1st Rifle Division

- 2nd Rifle Division

- 1st Heavy Artillery Regiment

- II Polish Corps

- III Polish Corps

- 3rd Rifle Division

- 6th Rifle Division

- 3rd Heavy Artillery Regiment

- Independent Units

- 7th Rifle Division

- Training Division - cadre

- 1st Tank Regiment

See also

Bibliography

- M. B. Biskupski, "Canada and the Creation of a Polish Army, 1914-1918," Polish Review (1999) 44#3 pp 339–380

- Joseph T. Hapak, "Selective service and Polish Army recruitment during World War I," Journal of American Ethnic History (1991) 10#4 pp 38–60

- Paul Valasek, Haller's Polish Army in France, Chicago, 2006

References

- Heiko Haumann. (2002). A History of East European Jews. Central European University Press. pg. 215

- ^ Julia Eichenberg (2010).The Dark Side of Independence: Paramilitary Violence in Ireland and Poland after the First World War Contemporary European history, 19, pp.231-248, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Carole Fink. (2006).Defending the Rights of Others: The Great Powers, the Jews, and International Minority Protection, 1878-1938. Cambridge University Press, pg. 227

- Holly Case, Cornell University (6 September 2011). "Review of Carole Fink, Defending the Rights of Others" (PDF file, direct download 146 KB). H-Diplo Review (at) H-Net: Humanities and Social Sciences Online. Cambridge University Press, 2006. p. 4. Retrieved 2013-04-11.

- ^ Carol R. Ember, Melvin Ember, Ian Skoggard (2005). Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World. Springer. p. 260. ISBN 0306483211.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Halik Kochanski (2012). The Eagle Unbowed. Harvard University Press. pp. 5–9.

- Anna D. Jaroszynska-Kirchmann (2013). Polish American Press, 1902–1969. Lexington Books. pp. 464–.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ William Fiddian Reddaway (1971). The Cambridge History of Poland. CUP Archive. pp. 477–.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - The Blue Division, Stanislaw I. Nastal, Polish Army Veteran’s Association in America, Cleveland, Ohio 1922

- Outline of the Wartime History of the 43rd regiment of the Eastern Frontier Riflemen, Major Stefan Wyczolkowski, Warsaw 1928

- Outline of the Wartime History of the 44th Regiment of Eastern Frontier Riflemen, Major Stanislaw Bobrowski, Warsaw 1929

- Outline of the Wartime History of the 45th Regiment of Eastern Frontier Infantry Riflemen, Major Jerzy Dabrowski, Warsaw 1928

- The Polish Army in France in Light of the Facts, Wincenty Skarzynski, Warsaw 1929

- Watt, R. (1979). Bitter Glory: Poland and its fate 1918-1939. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Subtelny, op. cit., p. 370

- ^ Alexander Victor Prusin (2005). Nationalizing a Borderland: War, Ethnicity, and Anti-Jewish Violence in East Galicia, 1914-1920. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. p. 103. ISBN 0817314598.

Note: the exact phrase 'Blue Army' is not being used inside this book. It refers to it as Haller's Army

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - ^ Pavel Korzec. (1993). Polish-Jewish Relations During World War I. In Hostages of modernization: studies on modern antisemitism, 1870-1933/39, Volume 2 Herbert Strauss, Ed. Walter de Gruyter: pp.1034-1035

- ^ Heiko Haumann. (2002). A history of East European Jews Central European University Press, pg. 215

- Justyna Wozniakowska. (2002). Master's Thesis, Central European University Nationalism Studios Program CONFRONTING HISTORY, RESHAPING MEMORY: THE DEBATE ABOUT JEDWABNE IN THE POLISH PRESS pg. 22

- Joanna B. Michlic. (2006). Poland's threatening other: the image of the Jew from 1880 to the present . University of Nebraska Press, pg. 117

- Feigue Cieplinski. "Poles and Jews: The Quest For Self-Determination 1919-1934" Binghampton Journal of History, University of Binghamptom, 6 May 2012.

- Marija Wakounig (28 November 2012). From Collective Memories to Intercultural Exchanges. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 196. ISBN 978-3-643-90287-0.

- Carole Finke. (2006). Defending the Rights of Others The Great Powers, the Jews, and International Minority Protection, 1878–1938. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pg. 230

- Alexander Victor Prusin (2005). Nationalizing a Borderland: War, Ethnicity, and Anti-Jewish Violence in East Galicia, 1914-1920. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, pg. 100."

- American Jewish Committee.(1920). American Jewish year book, Volume 22 . Jewish Publication Society of America pg. 250

- Howard M. Sachar. (2007). Dreamland: Europeans and Jews in the Aftermath of the Great War, Random House LLC: page 25.

- Tadeusz Piotrowski. (1998). Poland's Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918-1947, McFarland: page 43.

- General Haller's Visit to Boston Curtailed Jewish Telegraphic Agency. November 27, 1923

- Bnai Brith of Boston Decry Reception to Haller Jewish Telegraphic Agency. November 13, 1923

- William W. Hagen. Murder in the East: German-Jewish Liberal Reactions to Anti-Jewish Violence in Poland and Other East European Lands, 1918–1920. Central European History, Volume 34, Number 1, 2001 , pp. 1-30. Page 8.

- William Fiddian Reddaway, The Cambridge history of Poland, Volume 2, pg. 477, Cambridge University Press, 1971.

- Andrzej Nowak, Kronika Polski, Kluszczynski Publishers, 1998

- Kay Lundgreen-Nielsen, The Polish problem at the Paris Peace Conference: a study of the policies of the Great Powers and the Poles, 1918-1919, pg. 225, Odense University Press, 1979

- Manfred F. Boemeke, Gerald D. Feldman, Elisabeth Gläser, The Treaty of Versailles: a reassessment after 75 years, Volume 1919, pg. 324, Cambridge University Press, 1998

- ^ Goldstein, Edward. Jews in Haller's Army. The Galitzianer, the quarterly journal of Gesher Galicia, May 2002. Goldstein states: "Based on the evidence I have considered I conclude that: (1) individual Hallerczyki and probably units of Haller’s Army committed anti-Semitic atrocities while in Poland, and (2) thousands of Jews served in Haller’s Army. Cite error: The named reference "Goldstein" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- The New York Times. May 27, 1919. HALLER OFFICER; De Wolski Says Stories Do Injustice to Jews in the PolishArmy.

- Martin Conway, José Gotovitch. (2001). Europe in exile: European exile communities in Britain, 1940-1945. Berghahn Books pg. 191

- Stanley R. Pliska, "The 'Polish-American Army' 1917-1921," The Polish Review (1965) 10#1 pp 46-59.

External links

- Haller Army Website

- Józef Haller and the Blue Army

- "The Polish Army in France: Immigrants in America, World War I Volunteers in France, Defenders of the Recreated State in Poland" by David T. Ruskoski

- "A World War 1 Experience; Believe It Or Not"

- France in World War I

- Poland in World War I

- History of Poland (1918–39)

- Military history of Poland

- Polish armies

- Polish diaspora

- Polish–Soviet War

- France–Poland relations

- Military units and formations established in 1917

- Military units and formations of Poland in World War I

- Jewish Galician (Eastern Europe) history