| Revision as of 21:35, 17 November 2014 editRobert McClenon (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers197,127 edits →Gravitation / Relativity / Cosmology: be more specific← Previous edit | Revision as of 21:37, 17 November 2014 edit undoMihaister (talk | contribs)579 editsm →the value of a 0.022K capacitor?: wikilinkNext edit → | ||

| Line 467: | Line 467: | ||

| i have got non polarized polyester capacitior which has "0.022K400V" printed on it. | i have got non polarized polyester capacitior which has "0.022K400V" printed on it. | ||

| what is the value of cap in uF? | what is the value of cap in uF? | ||

| :That's a 0.022 µF capacitor rated for 400V. The letter "K" denotes 10% tolerance. See for an explanation of component markings. ] (]) 21:31, 17 November 2014 (UTC) | :That's a 0.022 µF capacitor rated for 400V. The letter "K" denotes 10% tolerance. I see that the wiki page on ] is pretty slim. See for an explanation of component markings. ] (]) 21:31, 17 November 2014 (UTC) | ||

Revision as of 21:37, 17 November 2014

Welcome to the science sectionof the Misplaced Pages reference desk. skip to bottom Select a section: Shortcut Want a faster answer?

Main page: Help searching Misplaced Pages

How can I get my question answered?

- Select the section of the desk that best fits the general topic of your question (see the navigation column to the right).

- Post your question to only one section, providing a short header that gives the topic of your question.

- Type '~~~~' (that is, four tilde characters) at the end – this signs and dates your contribution so we know who wrote what and when.

- Don't post personal contact information – it will be removed. Any answers will be provided here.

- Please be as specific as possible, and include all relevant context – the usefulness of answers may depend on the context.

- Note:

- We don't answer (and may remove) questions that require medical diagnosis or legal advice.

- We don't answer requests for opinions, predictions or debate.

- We don't do your homework for you, though we'll help you past the stuck point.

- We don't conduct original research or provide a free source of ideas, but we'll help you find information you need.

How do I answer a question?

Main page: Misplaced Pages:Reference desk/Guidelines

- The best answers address the question directly, and back up facts with wikilinks and links to sources. Do not edit others' comments and do not give any medical or legal advice.

November 13

Mitochondrial DNA questions

- Please, in the least number of words and in the simplest way you can - Except for ATP production, what is the other main function of the Mitochondria?

- What is the prevalence, in general, of known\defined Mictochondrial disorders? - What is the Ratio of Disorder\Births?

I guarantee these are not homework questions; Thank you, Ben. Ben-Natan (talk) 03:03, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- There are many different functions, really - biological structures and genes don't actually "know" what they are "for". The article mitochondria does list quite a few of them. If I were going to answer I might have talked about apoptosis, but the article seems to prefer uncoupled energy production (as per heat generation in brown fat) as the more important second function, and I can't really argue it.

- The article mitochondrial disorders actually does list those stats currently, and cites its sources - 1 in 4000 births, but only about 15% of the diseases due to mitochondrial DNA proper. I haven't looked at such stats in a long time, but they sound plausible enough. Wnt (talk) 04:04, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- 1. I never said or even clued that "Biological structures and genes know what they are for". I asked the question because I once read at a discussion here that Mitochondria have to main functions, 1 is ATP production and the other - well, that wasn't very clear from the text...

- 2. I couldn't understand what you meant at "about 15% of the diseases due to mitochondrial DNA proper"; did you mean that 0.0000375 births (15%/4000) are Mitochondrial proper? Ben-Natan (talk) 05:07, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

Question About the Reversibility of Gene Therapy

I apologize for my ignorance in regards to this, but is gene therapy theoretically always (fully) reversible or not? Futurist110 (talk) 03:46, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- As practically implemented, gene therapy is almost never truly reversible; it generally involves inserting bits of DNA into the cell; in theory this may be in a specific location (see adeno-associated virus), but in practice (as the deaths from leukemia attest) it can be less predictable. A clever approach might tend to pop out the preceding alteration, or be targeted to disrupt something that was added, but with varying degrees of success. It is however possible to make gene therapy that is designed from the beginning to be capable of being shut off; a laboratory mechanism in mouse studies involves using tetracycline to control transcription of an added gene. In theory such control mechanisms could be arbitrarily elaborate and sophisticated. In practice, it is still far too rare to see gene therapy even attempted in even the most straightforward situations where it should help. Wnt (talk) 04:11, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- Don't apologize for that!

- At present gene therapy is not permanent, when the modified cells die the new ones don't have the therapy. So in a way it's reversible. However there is no direct way to reverse the effects, if you wanted to do that you would essentially need more Gene Therapy. So it's also not reversible. Ariel. (talk) 08:24, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

The Lactose has a sweet taste

Maybe that's what gives the sweet taste to the milk. Am I right? and does it raise the glucose in the blood - generally? (not for a medical advice, but to the facts about Lactose) 5.28.177.33 (talk) 06:14, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, and slightly old milk is sweeter since the lactose gets hydrolysed into smaller sugars, which are sweeter. Yes, it does raise glucose since it has glucose in it, but not very much. Ariel. (talk) 08:27, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- Thank you 5.28.177.33 (talk) 12:11, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

Thermodynamics properties of chemical substances

| Incorrect use of valence - Otherwise not clear what is being asked. Robert McClenon (talk) 20:41, 14 November 2014 (UTC) |

|---|

| The following discussion has been closed. Please do not modify it. |

|

If the chemical and physical properties of the chemical substances are always dependent on their valence and their molecular structure of the chemical substance, so that did the thermodynamic properties of the chemical substances to been defined by valence of this chemical substances? Valence of what chemical substances is always been much, the valence of the carbonaceous gases or valence of the alkalic vapour and acid vapour (chemical vapours)?--Alex Sazonov (talk) 09:59, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

Note:I believe, that in natural nature always been only once electronic charges (single electronic charges or charges of the electron pairs), so that I would argue that the valence always determines the chemical and physical properties of all chemicals, but this did not negate the fact, that in natural nature are always been a chemical substances which had complex valence - complex chemical substances and chemical substances which had simple valence - simple chemical substances.--Alex Sazonov (talk) 15:00, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

|

Gases and valence

| Incomprehensible material Robert McClenon (talk) 20:37, 14 November 2014 (UTC) |

|---|

| The following discussion has been closed. Please do not modify it. |

|

What natural gases in natural nature always had a lot, the natural gases which had a much valence or natural gases which had a small valence?--Alex Sazonov (talk) 11:16, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

|

cushing's syndrome

A person suffering from Cushing’s syndrome will have symptoms that include rapid weight gain, particularly of the trunk and face (moon face) with sparing of the limbs. Why & how does the syndrome affect the body in this way? b.Could the consumption of hydrocortisone of 20mg daily to alleviate adrenal insufficiency also cause a “moon face” effect? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 113.210.35.128 (talk • contribs) 14:24, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- Sensitivity to hydrocortisone, which is what we call medically-administered cortisol, varies greatly from person to person (so it's not possible to give an accurate, simple answer to your question - the effects are too variable). The differential sensitivity of various types of adipose tissue (visceral and peripheral, among others - see some listed in that linked article) to the opposing effects of cortisol vs. elevated insulin levels that cortisol can stimulate, probably determines the pattern of fat redistribution. -- Scray (talk) 20:06, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

Looking for further reading on cosmic body physics particularly comets/soft bodies type and collisions

First is the bit I understand and what made me curious.

Was looking at , which shows the Lutetia big side up and marks the circles of their craters.

And then this one , which gives a sort of impression of two comets that collided and did not quite make escape velocity. So, I was think about the gravity and friction of when two bodies collide. Obviously the two had collided and caused a temporarily plastic surface, like, or even as, a wet blob, and eventually friction and other stuff brings it to a halt as the new single body.

However... Would the internal friction alone be enough to bring the surface to a settling halt? I assume the external tidal forces, such as the pull of the sun, would be the cause of the surface in the absence of any absorber of the collision force. Can anyone say a subject with particular focus on cosmology that will tell me stuff like if stuff outside the suns area of effect actually settles into a constant steady surface some time after impact, as the Lutetias is, and stuff about how that settling actually works out there?

I searched up stuff like collisions and gravity but of course it's a very specific item. There's probably not an article in it but aren't half of us wondering about comets and that today? :)~ R.T.G 15:32, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- The escape velocity of 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko is 1 m/s, less than walking speed. If it formed through two bodies colliding, it was an incredibly minor crash. Rmhermen (talk) 15:52, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- And it would also take a very long time for the two to approach each other at those speeds, maybe thousands of years ? StuRat (talk) 16:36, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- I think you're looking for information about hydrostatic equilibrium.

- On Earth, we use hydrostatic equilibrium to describe, say, water in a pipe; or oil-and-vinegar that have separated out into layers based on their different densities.

- In planetary science, we can use the models and terminology of fluid dynamics to study all matter. Everything is a fluid on a sufficiently long time-scale!

- One of the current elements in the definition of a planet is that the object's matter has enough self gravitation to achieve hydrostatic equilibrium. That means two things: there's enough material - and it's made of chemicals that are soft enough relative to its own mass - to squish into a spherical object. This process can take thousands, millions, billions of years.

- Comets are made of water and carbon dioxide ice, among others (methane and ammonia for some comets). They sometimes also contain a lot of other harder materials: to use the terminology of comet scientists, there are also "metallic" and "chondritic" (rock-like) chemicals. Depending on which theory applies to any specific comets, those chemical compounds are primitive - they evolved directly out of stellar nucleosynthesis products - so they have never been subject to processes of geological evolution. That means that the iron in a meteoroid or a comet was never "refined" by heat and pressure; the "rock" and "dust" have never been subjected to the usual earth-style "igneous rock"/"metamorphic rock" progression; and although exposed to the harsh environments of space, there's not a whole lot of physical erosion action. These materials are kind of strange! Over a long time - billions of years - the materials have been subjected to direct, unfiltered stellar radiation, and extremes of temperature and heat. This actually can chemically change some of their materials. Over billions of years, exposure to sunlight has an erosive effect, softening "rock" and turning it into dust! (Solar Wind and Micrometeorite Effects in the Lunar Regolith, (1977).

- Add on top of this that the comet's elliptic orbit cycles it through a variety of solar distances, ranging across several AU. Methane and ammonia and water and carbon dioxide - all of which might be gravitationally bound to the comet - can turn from liquid, to solid, to gas, depending on the effective planetary temperature of the comet. So, one day the comet might be a bunch of sand and gravel that's glued together by rigid ice - and the next, it might be a swampy clump of wet sand and metal fragments! When that happens, the material can re-shape.

- Last, but not least, there is a stronger force than gravity: electrostatics. The comet, and all of its gas and solid components, are blasted by highly energetic solar wind. Some of the atoms become ionized. When this happens, the material in the planet is subject to electrostatic attraction - or repulsion - and the strength of these forces can be orders of magnitude larger than the attractive force of gravity.

- If there is enough matter, gravity will win: the self-gravitation of all these particles will, over the long run, cause the materials to smush together into a nearly perfect sphere. For a comet the size of Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, this hasn't happened yet - and very likely won't happen for a very very long time, comparable to the lifetime of the solar system. It will always be irregular!

- Let me close with a pitch for one of my favorite books on planetary formation - one that doesn't pull any punches or leave out any equations! de Pater and Lissauer, Planetary Sciences - it was written by the scientists who worked on the extrasolar planetary mission of the Kepler Space Telescope - and it has an entire chapter on comets and meteoroids; and another entire chapter on planetary models of hydrostatic equilibrium!

- Nimur (talk) 16:42, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- Brilliant by User:Nimur. ~ R.T.G 00:00, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

What is the farthest you can communicate with an unlicensed (and legal) radio?

--Senteni (talk) 17:18, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- According to whose laws? --Jayron32 17:20, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- Well, US, Europe, although I suppose there must be an international aggreement on this, so all countries will let the same wavelength free.--Senteni (talk) 17:35, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- For starters, see Amateur radio, International_Amateur_Radio_Union, and pirate radio. maybe DXing has some interest as well. SemanticMantis (talk) 17:42, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- Note that it's not just a matter of what wavelength. Maximum transmission power, antenna size and other factors will be dependent on local laws. Also as those articles illustrate, it will depend on time of day and other factors. Additionally, "unlicensed and legal radio" is unclear. AFAIK, in many countries amateur radio operators can operate in frequencies and possibly with greater power without a specific licence for the radio, but they do need a licence themselves. Nil Einne (talk) 18:04, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- For starters, see Amateur radio, International_Amateur_Radio_Union, and pirate radio. maybe DXing has some interest as well. SemanticMantis (talk) 17:42, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- Well, US, Europe, although I suppose there must be an international aggreement on this, so all countries will let the same wavelength free.--Senteni (talk) 17:35, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- For the purposes of this question... does the radio signal need to propagate wirelessly? Nimur (talk) 19:19, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- I think I know what you're getting at, but radio says "Radio is the radiation (wireless transmission) of electromagnetic signals through the atmosphere or free space." (emphasis mine) - Do you really commonly refer to signals sent through a wire as "radio signals"? SemanticMantis (talk) 19:33, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- Actually I was thinking of a similar thing. Namely whether the OP was truly restricing the question to parts of the EM spectrum generally considered radio which includes some stuff also sometimes considered microwave and other things, but generally never stuff called light. Because high powered laser laws are still often limited albeit increasingly getting more stringent thanks to pressure from idiots misusing such lasers (and even then, some countries restrict readymade laser devices much more heavily than the diodes). Of course this illustrates another point, you can theoretically communicate quite far with lasers depending I think on atmospheric conditions and other factors. Possibly further than with an unlicenced radio even one designed to send to space (although I'm not sure). However there's no one to actually receive your line of sight signal somewhere in outerspace. Nil Einne (talk) 13:44, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- I think I know what you're getting at, but radio says "Radio is the radiation (wireless transmission) of electromagnetic signals through the atmosphere or free space." (emphasis mine) - Do you really commonly refer to signals sent through a wire as "radio signals"? SemanticMantis (talk) 19:33, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- For the purposes of this question... does the radio signal need to propagate wirelessly? Nimur (talk) 19:19, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- If you are talking 2-way Line-of-sight radio the Marine VHF radio article mentions some ranges. I do not see refs to support all the info though. I would imagine radios at sea would be more consistent in performance since there is no unpredictable terrain.

It mentions 111 km with 25 watt transmitter.I went through some ads for handheld high powered 2-way radios and they went up to 5 watts. Richard-of-Earth (talk) 19:36, 13 November 2014 (UTC)- Looking around some more that article has to be wrong. This mentions line of sight on a curved earth max range is 13.3 miles (21.4 km). Richard-of-Earth (talk)

- I think the article might still be right. The marine VHF article says ~100 km for tall ships or antennae mounted on hills. Your recent link says 13 miles for a 100 ft antenna. Surely large commercial vessels will have much higher antennae, and consequently longer range, as described by the equations at line-of-sight propagation. (I did not check all the math, just saying that the two pieces of info are not necessarily contradictory) SemanticMantis (talk) 20:04, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- Larger ships that travel far from land will also have access to HF radio (which is not limited to line of sight), or ultra-high-frequency radio (or microwave radio) satellite uplink (which is line-of-sight to an orbital digital radio repeater). Nimur (talk) 20:07, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- Hmm. The OP really does need to give more specifics. this article mentions the different types of radios, their ranges and needs for licenses (in the US I am sure). If you are transmitting for an aircraft, up to 200 miles! So you have to buy or charter a plane too. Of course, you can walk into a store, buy a disposal cell phone and communicate via radio to anywhere on planet, no licence needed. Richard-of-Earth (talk) 20:31, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- In many countries, the mobile phone or its transceivers will however need to be appropriately licenced. (At the very least, in most cases the spectrum they are operating can only be used because whoever's network your connecting to paid the government good money to be allowed to use said spectrum. And said operator usually sets standards which you are required to follow, failing which they may ask you to stop using their network or even take legal action against you.) Nil Einne (talk) 13:28, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Hmm. The OP really does need to give more specifics. this article mentions the different types of radios, their ranges and needs for licenses (in the US I am sure). If you are transmitting for an aircraft, up to 200 miles! So you have to buy or charter a plane too. Of course, you can walk into a store, buy a disposal cell phone and communicate via radio to anywhere on planet, no licence needed. Richard-of-Earth (talk) 20:31, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- Larger ships that travel far from land will also have access to HF radio (which is not limited to line of sight), or ultra-high-frequency radio (or microwave radio) satellite uplink (which is line-of-sight to an orbital digital radio repeater). Nimur (talk) 20:07, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- I think the article might still be right. The marine VHF article says ~100 km for tall ships or antennae mounted on hills. Your recent link says 13 miles for a 100 ft antenna. Surely large commercial vessels will have much higher antennae, and consequently longer range, as described by the equations at line-of-sight propagation. (I did not check all the math, just saying that the two pieces of info are not necessarily contradictory) SemanticMantis (talk) 20:04, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- Looking around some more that article has to be wrong. This mentions line of sight on a curved earth max range is 13.3 miles (21.4 km). Richard-of-Earth (talk)

- Technically you can communicate around the world, just use a low frequency. Looks like below 9khz is unlicensed (not certain though). But your bandwidth will be tiny. Some links to check: ELF SLF ULF VLF Ariel. (talk) 20:40, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- Technically, it is prohibitively difficult for an amateur on a limited budget to broadcast a strong signal at VLF or lower frequency. A quarter-wave antenna at 30 kHz would be 2.5 kilometers high. VLF and lower frequency transmitters tend to be operated by scientific researchers and by well-funded governments. Nimur (talk) 00:17, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- ???? The OP is asking about unlicensed but legal transmitters. Hams (with legal licensed transmitters) have been doing EME (that's about all most half a million miles) since about the 1960 and all without a government grant of billions of dollars. For lower frequencies, a British and New Zeeland ham duo were able to communicate at 2 (two) watts, by careful frequency and phase matching and signal period. A technique, later adopted many decades later by JPL in order to pull in the very weak 20 watt transmissions from Voyager one & two (and they added a bit of computerized statistical analysis as well, to speed things up, and to help filter out the signal from the background noise). Most unlicensed but legal transmitters are in the upper frequency range so don't travel much further than the visible horizon during time of normal propagation. During time of tunnelling however, US police VHF communications have been hear in the UK. I have also received VHF from a guy whilst walking his dog on the shores of Holland who had only a 5 Watt transceiver but due to atmospheric tunneling he came in loud and clear. Sea water (being conductive) can create a dielectric wave guide taking the signal way beyond the radio horizon. So lets not hear any more of this “Technically, it is prohibitively difficult for an amateur on a limited budget“ nonsense. --Aspro (talk) 14:37, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Most HAMs aren't transmitting below 50 kHz - ergo, "VLF", "ELF", and so on. "VHF" and "VLF" are one letter and many hundreds of thousands of dollars of equipment apart. Nimur (talk) 16:04, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Most HAMs may not be transmitting below 50 kHz but some do and quite successfully without billion dollar grants. But this is with legal licensed equipment. Most no-licensed-required legal equipment (as asked by the OP) uses VHF and above.--Aspro (talk) 16:29, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Most HAMs aren't transmitting below 50 kHz - ergo, "VLF", "ELF", and so on. "VHF" and "VLF" are one letter and many hundreds of thousands of dollars of equipment apart. Nimur (talk) 16:04, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- ???? The OP is asking about unlicensed but legal transmitters. Hams (with legal licensed transmitters) have been doing EME (that's about all most half a million miles) since about the 1960 and all without a government grant of billions of dollars. For lower frequencies, a British and New Zeeland ham duo were able to communicate at 2 (two) watts, by careful frequency and phase matching and signal period. A technique, later adopted many decades later by JPL in order to pull in the very weak 20 watt transmissions from Voyager one & two (and they added a bit of computerized statistical analysis as well, to speed things up, and to help filter out the signal from the background noise). Most unlicensed but legal transmitters are in the upper frequency range so don't travel much further than the visible horizon during time of normal propagation. During time of tunnelling however, US police VHF communications have been hear in the UK. I have also received VHF from a guy whilst walking his dog on the shores of Holland who had only a 5 Watt transceiver but due to atmospheric tunneling he came in loud and clear. Sea water (being conductive) can create a dielectric wave guide taking the signal way beyond the radio horizon. So lets not hear any more of this “Technically, it is prohibitively difficult for an amateur on a limited budget“ nonsense. --Aspro (talk) 14:37, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Technically, it is prohibitively difficult for an amateur on a limited budget to broadcast a strong signal at VLF or lower frequency. A quarter-wave antenna at 30 kHz would be 2.5 kilometers high. VLF and lower frequency transmitters tend to be operated by scientific researchers and by well-funded governments. Nimur (talk) 00:17, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- I have no doubt that some amateur radio enthusiasts may try to transmit VLF; but they probably fail to generate very strong signals. This is what a VLF transmitter looks like: NAA as viewed from two miles away. That is not a grouping of several dozen different VLF aerials: all of those towers are the radiating elements for one single VLF transmitter. The wavelength of the center-frequency is about eight miles. So, if you wanted to build a crappy, inefficient, barely functional amateur-grade whip antenna (instead of one of these sophisticated multi-element radiator arrays that the Navy uses), you'd still need a piece of wire five miles long, and you'd need to somehow attach it to a tower that would be taller than the tallest structure ever built by humans. At wholesale prices, the wire-runs alone would cost upwards of $60,000, but the engineering and construction costs would be ... a little more complicated to estimate! That's at 24 kHz. Lower frequency radio, like ELF, corresponds to even longer wavelengths.

- In March 2014, HAM operator W2ZM claimed to transmit trans-Atlantic signal at 29.499kHz on WH2XBA. I would go so far as to say, this level of equipment is non-amateur. In fact, it is actually regulated as radio licensed for scientific research.

- Let me re-iterate: I have no doubt that some amateur radio enthusiasts may try to transmit VLF; but they probably fail to generate very strong signal that would be suitable for long-distance propagation. It is much much much more efficient for a HAM to use an HF transmitter and use the skywave effect to transmit over the horizon. Nimur (talk) 18:36, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Oh Boy! Allow me re-iterate. The OP is asking about Legal but unlicensed' apparatus. What has power got to do with it? See Shannon–Hartley theorem. The VLF image you referred to, is that high, because it is more efficient than it would be lower down, but a lower antenna is still going to radiate. Have you heard of antenna that are λ/2, λ/4, λ/8 high and in length etc. Right. So why oh why, does one need five miles of very expensive sleeved cable cable costing $60,000 like you linked to? It is up in the air -it does not need to be copper or have any insulation (use plain aluminum) and just a mile will do. $500,000 dollar towers ? Answer: String the antenna from tree to tree. If one has to have all ones teeth veneered by a dentist because one drank too much coke and soda pop as a child, then in comparison, the cost of an amateur VLF antenna and associated equipment is hardly astronomical- is it? -Finally, the OP asks about Legal frequency but unlicensed. Most frequencies above 9 kHz have been allocated by the ITU. So in answer to the OP's question its about 3800 miles in normal day/night conditions with current practices; unless one is doing EME work but one will probable require a license for that in many countries as the side lobes could cause interferance. See and I quote:McIntyre needed no FCC license to transmit on 8.971 kHz, since the Commission has not designated any allocations below 9 kHz.--Aspro (talk) 21:25, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

- PS. Do you know what a whip aerial is and why they are used, together with their efficiency and suitability in the right application? You say “barely functional amateur-grade”? Look at the specs and compare them to commercial (cheap (?) and cheerful) whips that cost an arm and a leg. Then see if you can find the fallacies you're using from this List of fallacies. Just asking (;¬)--Aspro (talk) 21:59, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

- The article you really need to read is Tropospheric propagation and the short answer is several thousand miles under ideal conditions. For the purposes of this post I am assuming the OP is referring to unlicensed UHF hand-held transceivers that operate near 460 MHz in most countries (where they are legal). Roger (Dodger67) (talk) 14:16, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- There are also some frequencies that have unlimited radiation regulations. 13.56MHz used to be a frequency that was chosen for certain equipment because it wasn't regulated. --DHeyward (talk) 00:05, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

Why are we able to see light from almost the time of the big bang, should it not have got passed us?

I know that the further away an object is, the further back in time you're looking at that object, it's simply because light takes time to reach us, and as a result we are able to see objects that are over 10 billions years now, to almost to the time of the big bang itself. The question I have is how come we are able to see that light given that everything started from a single point and that everything escaped from that point, and given that light goes faster than us, us made of matter, that light should have passed us almost right from the beginning and should now be impossible to see, so my question is why are we able to see light that came from almost the time of the big bang given that that light should be out of reach? Joc (talk) 19:55, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- That is because space is glowing like a cooling ember. We cannot see the fire before the ember though. Plasmic Physics (talk) 20:21, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- That doesn't really answer the question. Vacuum or space can not radiate light (even if you had the energy, where would the momentum go?). So what is glowing? Ariel. (talk) 21:44, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- You are taking my metaphor too literally, I mean that even though it's not the honest truth, space itself may as well be glowing. The CMB was caused by the gas in the early universe cooling down. However, the rate of expansion out-paced the speed of light, and so the light from the glow is delayed. It is effect as hearing a lightning strike sometime after the matter, due to the difference between the speed of light, and speed of sound. Plasmic Physics (talk) 01:04, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- First, it's not accurate that everything escaped from a point. A better analogy is that of an expanding balloon, with two dimensional creatures living on the surface of the balloon. To the 2D creatures, there is no third dimension. Their universe is expanding, but there's no point in space that everything is escaping from.

- We can see almost to the Big Bang because at that time, we were moving nearly at the speed of light relative to the point we now see. The speed of light was so close to the speed of expansion that light only managed to catch up after 14 billion years. --Bowlhover (talk) 21:55, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- See Inflation (cosmology) for why light got left behind. Dbfirs 23:21, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- No, inflation is not really it. The balloon analogy is better. Imagine a constantly growing balloon (ok, there is some inflation ;-). We are living on and looking along the surface of the balloon in this reduced dimension. But no matter how far you look, there is always a piece of the balloon that is that far away, and from which light has travelled for a corresponding amount of time. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 00:04, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- OK, point taken. Also, inflation happened before photons of light came to exist, and long before there were stars to shine, so the balloon started partially inflated. Perhaps a constantly stretching flat rubber sheet would be a better analogy if you believe that space is flattish. Dbfirs 00:27, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- No, inflation is not really it. The balloon analogy is better. Imagine a constantly growing balloon (ok, there is some inflation ;-). We are living on and looking along the surface of the balloon in this reduced dimension. But no matter how far you look, there is always a piece of the balloon that is that far away, and from which light has travelled for a corresponding amount of time. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 00:04, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

Bowlhover: I agree that matter was going at almost the speed of light at the moment of the big bang but now we are going much slower, it seems to me that the light from the big bang should have passed us long ago.

Plasmic Physics: I agree that the CMB (Cosmic Microwave Background) is like the amber of the "explosion", an ambient light all around us that came from the big bang, but unless I'm mistaken, what we are actually seeing are very old galaxies that existed almost at the beginning of the universe, and again, how come we can see them, how come the light has not passed us and make them impossible to see???

Stephan Schulz: the balloon analogy seems to best answer to my question; both me and the far away galaxy are moving apart, that means that light has a longer distance to travel, which allows me to see further in the past. It seems like a race condition, the speed of the expansion of the universe against the speed of light. Would be nice to get details on that. Joc (talk) 22:14, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- See Metric expansion of space for details of the race. The expansion is currently accelerating. My point was that space had a head start. Matter as we know it (three states of atoms) didn't exist immediately after the Big Bang. Dbfirs 22:28, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Joc, the thing to understand is that the Big Bang didn't happen at a place. From our perspective, it happened at all places. All of space originated from the Big Bang, and consequently, all of space was filled with hot plasma in the initial moments after the Big Bang. In essence, when we look deep into space in one direction and see the cosmic microwave background, we are seeing what the after effects of the Big Bang looked like in that particular location a long time ago, and when we look in a different direction, we are seeing the after effects of the Big Bang somewhere else a long time ago. The Big Bang affected all of space, so if you look a great enough distance in any direction, you'll eventually see light that originated from the era shortly after the Big Bang itself. And the light you'll see reflects the impact of the Big Bang on that specific region of space far, far away (it's nearly the same in all direction, but people who study the cosmic microwave background can gain big insights from small difference depending on where you look in space). Also, the cosmic microwave background was created by the glow of recombination (cosmology), a side-effect of the universe cooling after the Big Bang and forming the first atoms (instead of ionized plasma). It predates the formation of galaxies and stars. Dragons flight (talk) 23:07, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- That it happen in "all places" implies that the universe is infinite, that also implies that light has an infinite amount of space to travel, and so it implies that we could look an infinite amount of time in the past, even before the big bang! Now I know that's wrong, but I don't know how it's wrong. I'm NOT interested by the CMB, what we measure is it's temperature and it glows everywhere; what I'm interested is that I read that we can actually see galaxies from very near the time of the big bang, and that we can see them clearly enough to be able to tell they they are "primitive", that they didn't have the time to form structures such as spirals for example, this is not the diffuse light of the CMB but light from a very precise point in space and time, the thing I don't understand is how those photons didn't get passed us since they are faster than us, given that everything came from the same point (if everything is moving away, reversing the time arrow, implies that everything came from the same point).

- The universe may be infinite, or it may simply be far, far bigger than the part of it that we can see. Either theory is consistent with cosmology and the shape of the universe as we know it. The expansion of the universe makes many things confusing, but lets ignore that for a moment. Ignoring expansion, we would assume that the oldest galaxies formed ~13 billion years ago, in a region of space ~13 billion light years away, using matter and energy the Big Bang left in their local region of space. As far as we can see, the Big Bang left a nearly uniform density of matter everywhere, and it did so as far back in time as we can see. In practical terms, that's what it means that the Big Bang affected all of space, it deposited nearly uniform matter everywhere we can see at the very beginning. That may continue literally forever (an infinite universe), or it may stop somewhere beyond the visible universe that we can see, but either way all of space for as far away as one can choose to look, is filled with matter. Incidentally, the CMB is the limit of how far one can look. At that point you are seeing the glow of the Big Bang, and no light older than the CMB survived.

- For a slightly more nuanced description, that includes expansion, one would say that the earliest galaxies formed ~13 billion years ago in a region of space that is now ~40 billion light years away. The extra ~30 billion light years is associated with the expansion of space, but the light only traveled ~13 billion years to reach us because at the time it departed the two regions of space were much closer. Even accounting for expansion though, the far away region of space 13 billion years ago already had a similar density of matter as the region of space we presently live in had 13 billion years ago. The Big Bang deposited matter everywhere we can see during the very earliest moments of time (e.g. inflation), well before those early galaxies formed.

- To return to the balloon analogy, the universe is like the surface of a balloon, and the density of matter can be thought of as like the thickness of the rubber. As the balloon expands, all points get farther away from one another and the local density of matter (i.e. rubber) decreases. The universe stretches and thins. However, the balloon always had rubber everywhere, it was created that way. No matter how you shrink or expand the balloon, there is no point in time where the rubber vanishes, it simply becomes more or less dense. On cosmological scales, the matter in the universe is the same way. The instant of the Big Bang created the universe (i.e. the balloon) with matter everywhere. The matter was then stretched and expanded, becoming less dense, but there was no region of space (as far as we can see) that ever lacked for matter. Dragons flight (talk) 20:23, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

November 14

All the different dimensions

Do I understand correctly that we, you and I (and everything) are present in all the dimensions at once? Sometimes people talk about something coming from another dimension as though it came from a different universe whereas I have always thought of dimensions as being something we have a position in. Thus instead of coming from a different dimension, some object or creature might come from a different position within that dimension to our position in that dimension and thus become observable to us? Is that wrong? --78.148.109.47 (talk) 05:21, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, yes, no. Plasmic Physics (talk) 05:48, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Is it so simple? Is time a dimension? Am I currently "present" at all points in time? Block universe and multiverse might be of interest when thinking about this question. SemanticMantis (talk) 16:51, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, time is normally considered a dimension, but behaves differently than the other dimensions, for reasons that cannot be explained in current physics. When something is said to have "come from a different dimension", it usually means that it is said to have come from a higher-order spatial dimension, presumably a spatial dimension with full extension that we cannot observe. The universe that we can observe consists of three spatial dimensions and time. Some Theories of Everything have various additional dimensions that are "rolled up". So if something really has come from a dimension beyond the three that we can observe, it is a matter of terminology or philosophy whether it comes from another universe or an aspect of this universe that we cannot observe. Robert McClenon (talk) 17:07, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Is it so simple? Is time a dimension? Am I currently "present" at all points in time? Block universe and multiverse might be of interest when thinking about this question. SemanticMantis (talk) 16:51, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, yes, no to your questions also. Plasmic Physics (talk) 03:55, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

- "Yes, yes, no" to my questions? I wasn't asking questions. Does that mean yes, yes, and no to the OP's questions? Robert McClenon (talk) 22:32, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

- No, the indent level indicates that I was responding to Mantis. Plasmic Physics (talk) 00:23, 17 November 2014 (UTC)

- See Flatland.—Wavelength (talk) 17:24, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Be aware that Flatland is primarily a social satire rather than a scientific textbook, although I can second Wavelength's recommendation. Tevildo (talk) 19:50, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Yeah Flatland's coverage of 2D life is exceedingly patchy and inconsistent. I don't know why people still recommend it for that reason. A VASTLY better book about a 2D world is "Planiverse" - which is modern, has lots of clever insights and an actual, interesting plot. SteveBaker (talk) 21:19, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Be aware that Flatland is primarily a social satire rather than a scientific textbook, although I can second Wavelength's recommendation. Tevildo (talk) 19:50, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- I wonder if you are actually talking about quantum states, as in the Schrödinger's cat, for example an electron exist in several quantum states simultaneously, so is every particles in the universe, so we would be into an Multiverse, and to my knowledge it's not possible to go from one "universe" to another, a bit like it's impossible to have a coin with a single face, both sides exist or none exist. Joc (talk) 21:03, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- In theories with small compactified extra dimensions, ordinary matter spans the entirety of the extra dimensions—it's "fat" in the extra dimensions, if you like. Matter at much higher energies can be "thin" and have a position in the extra dimensions, but it will always be visible to ordinary matter because the ordinary matter is everywhere. In braneworld models, ordinary matter is stuck to a lower-dimensional surface (the brane), so it does have a position in the higher-dimensional space. However, I don't think there's any way for higher-dimensional objects not attached to a brane to exist in those models. There's nothing out there except gravity. The idea, common in fantasy/SF stories, that you could see a slice through a higher-dimensional object as it passed through our lower-dimensional world is not consistent with any physical theory I've heard of. -- BenRG (talk) 23:02, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

Designing experiment to compare thermal clothing performance

I was thinking of designing and performing an experiment at home to determine the performances of different items of thermal clothing and I was wondering if someone might care to contribute to ensure that I don't miss any opportunities and flaw my experiment.

I thought I could simulate the body with a hot water bottle, placing a temperature sensor on the bottle and putting the thermal clothing over the bottle. Then the drop of the temperature could be logged over time. I would also measure the temperature of the air in the room and weigh the item of clothing excluding the sleeves. I would perhaps repeat the experiment with an additional, unvarying layer (e.g. a thick jumper) and with a fan blowing on the bottle/clothing from a fixed angle and distance. I could use a computer fan with known manufacturer specifications to give an indication of the amount of air being moved. I suppose I would also need an accurate hygrometer to know how cooling the moving air would be?

Do I need other sensors? Should I redesign the experiment?

I want to produce a table that will allow me to determine which clothing offers the best weight to insulation ratio and the best cost to insulation ratio. I guess I'll need to record the dimensions of the garments since some will be more generous than others.

Are the thickness and permeativity to sweat worth consideration?78.148.109.47 (talk) 05:40, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- The thermal performance of some garments is likely to vary between them being worn, and simply draped over an object (e.g. thermal underwear is generally stretched when worn). MChesterMC (talk) 09:27, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- ...which can be good or bad, as it may restrict heat loss by air circulation. At least in Germany, some major outdoor stores have cold chambers with infrared cameras where they allow you to try out your particular piece of clothing on your particular body, and look at the heat loss. Some also simulate wind in the chamber periodically. However, this is more a marketing gimmick (with windows for your friends to look in and make fun of you), and probably not suitable for exact measurements or large-scale comparisons. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 10:56, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- One point that hasn't been mentioned yet - you need a control for your experiment to have meaningful results. A hot-water bottle that's not wrapped in anything would be a possibility. Note also that the results will depend on the temperature (and humidity) of the room, which (presumably) isn't very precisely controlled, so you'll need to factor this in. A third point - weight is not the only important parameter when it comes to how comfortable clothing is, otherwise we'd all wear polystyrene clothing in winter... Tevildo (talk) 19:05, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- There is an important difference between a hot water bottle and the human body. We generate heat internally - so the temperature of a human wouldn't vary much over the duration of the experiment, although we might have to resort to shivering and such to keep the body at the right temperature throughout. But the hot water bottle will gradually cool off. So perhaps we could imagine some kind of garment that releases heat very easily at body temperature, but insulates more and more effectively as the temperature drops (or vice-versa). That garment would perform much better in the experiment than it would with a human subject. Now, I can't think of a material that would act like that - but the whole thing about an experiment is to find that out and not be tricked by things like that. SteveBaker (talk) 21:15, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Then use an electric blanket. Changing out the three-position switch on most with a variable rheostat should allow you to generate a constant temperature. You wouldn't even need a blanket to get to 98.6; you'd merely need the surface of the blanket to be able to maintain skin temperature, which for most people is somewhat less than body temperature. Use an electric blanket, calibrate it to output constant skin temperature, and wrap it in various fabrics. Measure the rate at which the outside of the fabric heats up, and you'll know which fabrics are better at retaining heat and which release it faster. --Jayron32 03:05, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

- It seems to me that the technique will measure diffusive cooling pretty well but won't measure radiative cooling. I don't know how important that is on the whole -- it definitely comes into play in some situations. For example a person inside a tent at night will stay warmer than a person outside under a starless sky, even if the air temperature is the same and there is no wind, because the tent reflects radiation back. Looie496 (talk) 02:45, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

- Something that hasn't been mentioned is how you will secure the fabric to the hot water bottle, and how the assembly will be held in the test chamber. I would suggest you sew the fabric samples into identical "water bottle cozy" shapes, such that you can slip the water bottle in and out, with a hook sewn in so you can suspend the assembly. This will help to ensure identical test conditions, which you won't get by just draping fabric over the hot water bottle. StuRat (talk) 02:53, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

As a home setup that is simple and economical, what about having a glass with a fixed amount boiling water surrounded with insulation except at the top which would have the garment, being careful not to touch the water, and then after a fixed amount of time, measure the temperature and the weight of the water, that will give you a relative measurement of the thermal insulation and how well the garment can "breath". You could also touch the garment to see if it feels wet. If you repeat the experiment with the same setup every times and compare the data for each garment you should get a good idea of the relative merit of each garment. Obviously a much better test would be to have someone wear the garment and do a standardized workout and ask for their impression, that would be a much more thorough and more meaningful evaluation. Joc (talk) 18:50, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

Shear strength of soil

Does the size of aggregate in soil affect internal friction angle? My assumption is that finer aggregates are more likely to be rounded reducing it and also means there would be more weakness planes in between aggregates reducing cohesion. Am I correct?

- I'm not sure what you mean by "aggregate" here, as this normally refers to a construction material of specially graded material rather than soil. As stated in the soil article: "Soil particles can be classified by their chemical composition (mineralogy) as well as their size. The particle size distribution of a soil, its texture, determines many of the properties of that soil, but the mineralogy of those particles can strongly modify those properties. The mineralogy of the finest soil particles, clay, is especially important." In other words, the type of material at least as important than the grain size. And you certainly can't assume that finer grains are more likely to be rounded.--Shantavira| 16:39, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, size of aggregate will affect shear strength, but I agree with the above that smaller particles are not necessarily more rounded. The word "aggregate" is indeed used in soil science (in the field of study, as well as our related articles). We have pretty good articles at soil structure and soil mechanics that discuss the effect of grain size and other features on soil properties. SemanticMantis (talk) 16:48, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

Why the DAF-2 gene is not extinct?

Hi there,

I've read about Daf-2, and I wonder why that gene has been surviving?

Exx8 (talk) 10:29, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Because organisms who carry the gene don't die before they have a chance to pass it on to offspring. --Jayron32 10:40, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, and even if an allele does confer some disadvantage, it may remain in the population indefinitely if it also confers some benefit. In this case, DAF-2 seems to have a functional role in regulating reproductive development, and knocking it out may indeed prevent the organism from being able to reproduce at all. Also, the locus takes part in controlling formation of Dauer_larva, which seems to confer a large benefit for the overall population. Some academic papers on the topic here . SemanticMantis (talk) 16:42, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Note also that even our article says "Disabling DAF-2 arrests development in the dauer stage which increases longevity, delays senescence and prevents reproductive maturity". Nil Einne (talk) 19:27, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, and even if an allele does confer some disadvantage, it may remain in the population indefinitely if it also confers some benefit. In this case, DAF-2 seems to have a functional role in regulating reproductive development, and knocking it out may indeed prevent the organism from being able to reproduce at all. Also, the locus takes part in controlling formation of Dauer_larva, which seems to confer a large benefit for the overall population. Some academic papers on the topic here . SemanticMantis (talk) 16:42, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

Uniqueness of Human Bones?

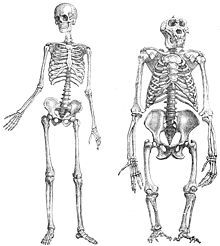

If presented with a *large* box containing one set of adult male bones each from the 7 species of Great Apes how many of the bones of the Human would be distinguishable from the others 1) by a layman, 2) by a Forensic Anthropologist without tools 3) by a Forensic Anthropologist with a full lab. I'm guessing #3 would be all, but for #1, I'm guessing a good number, but I'm not sure if #2 would be all (Free floating ribs and individual vertibrae for example, I guess would be tough. (Would adding any other animal beyond the great apes make things more complicated other than simply increasing the number of bones.Naraht (talk) 15:16, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- For #2, it's going to vary a great deal depending on the background of the individual. Primatology is often not part of the curriculum for, say, undergrad anthropology courses. It would be quite easy to get a doctorate in that field without any more than a passing knowledge of what chimp bones look like. The advantage they'd have over a layperson is their deep familiarity with human osteology. On the other hand, if their undergrad work or grad studies included courses in primatology and/or palaeoanthropology and/or comparative anatomy, then they'd be much better off. Even having a personal interest would greatly increase their ability. The answer for #1 would range from folks with almost literally no knowledge of what a skeleton looks like (I've seen an archaeology undergrad identify a squirrel pelvis as its skull) all the way to amateur bone hunters that could give the pros a run for the money. For #3, the biggest piece is probably not having a "full lab", but having a decent light and magnifying lens with a really good book. Matt Deres (talk) 16:09, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- If the bones are fresh enough, DNA analysis should be able to cluster them into disjoint sets easily enough with a good lab. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 19:21, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Agreed. My point was simply that the expensive stuff is not necessary. Visual examination, especially with the aid of a diagnostic reference book, would be enough. Matt Deres (talk) 15:31, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

- The human foot, skull, and teeth are so different from the other apes, I would expect a high-school biology educated layman who could identify these would know right away whether he was dealing with an ape or a human. Likewise, the limb proportions, relative length of the thumb, pelvis breadth, spine curvature, location of the foramen magnum, ribcage shape, and bowing of the legs are quite distinct. Many of these things are diagnostic of human, non-human on their own, and even if you only had a hand, if you knew how to articulate it it would be quite obvious from the thumb and finger proportions. See this website on man vs gorilla, these images at google, and our articles, human leg and comparative foot morphology. μηδείς (talk) 23:20, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- As for #1, the skull alone should tell the average layman whether it's a human or some other extant primate. However, if you included some extinct primates, like Neanderthals, that would make it tougher. The remaining bones would be harder to identify, in isolation. Only by laying out the bones in the right order to reconstruct the individual would you get a sense for the proportions of the bones, and hence the species. A further complication would be if the set of bones was atypical for that species. For example, the Elephant Man's skull might be difficult to identify as human. StuRat (talk) 15:48, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

- Neanderthals were human, they interbred with us. The premise is a full set of adult male bones, so the skull alone is the end of the story. Even comparing the femur and the pelvis is enough to draw an instant conclusion. Once you've found a heel the quiz is over. μηδείς (talk) 19:43, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

- The original question was how many of the individual bones could be identified as human - clearly, identifying a set if you know they all belong together is easier. Dealing with adult specimens makes it simpler though - if you don't know the age, the size may not help much, and the differences between species tend to become more apparent with age. AndyTheGrump (talk) 19:56, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, but we are still presented with a full set of bones from two individuals, not just one carpal bone, which are the only bones I can see as problematic for a layman with a book, although they are bigger in gorilla hands than the are in ours.

- If the sets could be sorted (a layman with a book should be able to do this) none of the bones would be mistaken. A forensic anthropologist would not need a lab, as he'd rearticulate the human first, from head down and sine out, then the gorilla, then check for mistakes. The entire anatomy of a human is modified by two things. The human hands are designed to allow the tip of the thumb to touch the tips of all four fingers, not for brachiation or knuckle walking

- The rest of the skeleton, the feet, legs, pelvis, spinal curvature, and base of the skull are all designed for a permanent upright stance. our legs are long, straight, gracile and knock-kneed compared to apes. Our pelvis is small compared to our femur, but our head is large compared to our pelvis. The hole where our spinal chord enters the skull is on the bottom, in apes further towards the back.

- As intelligent social animals, we don't have fangs for canines, but we do have chins and foreheads, effectively expanding our faces and brain capacity in comparison to apes. The list is endless. μηδείς (talk) 05:02, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

- "Designed"? AndyTheGrump (talk) 05:06, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

- You obviously know exactly what was meant, or you wouldn't have asked the question. So I'll just assume you are particularly grumpy today, and ignore it. μηδείς (talk) 20:41, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

- Design is just an expression, anyway. InedibleHulk (talk) 08:04, November 17, 2014 (UTC)

- "Designed" as in "designed by Mother Nature," i.e. by evolution. Not actively designing like an architect, but passive design by natural selection. ←Baseball Bugs carrots→ 13:37, 17 November 2014 (UTC)

- "Designed"? AndyTheGrump (talk) 05:06, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

- The idea that there's a binary determination between same-species/not-same-species, and that the determination is "can interbreed" is simplistic. Even among extant species that's kind of the "high school" understanding of the subject, and when comparing long extinct species with modern ones the question is even more complicated.

- Beyond that, we don't even know if Homo Sapien/Neanderthal breeding normally produced fertile offspring, or just on very rare occasions. (Just like Lion/Tiger breeding will usually create infertile offspring, but on rare occasions the offspring is fertile. Does that automatically make them the "same species"? Clearly not.)

- In fact, while the theory that our Cro-Magnon ancestors interbred with Neanderthals has gained a lot of support, it is far from proven, and even among supporters of the theory, many of them believe that it only 'worked' with Cro-Magnon mothers, and didn't work the other way around. Does that make them the same species? Or different species? Neither. "Species" is an arbitrary distinction. Anyone suggesting otherwise for the purposes of nit-picking is more wrong than the person they're nit-picking! 75.69.10.209 (talk) 07:29, 17 November 2014 (UTC)

- You contradict yourself. You say a binary distinction is arbitrary, and then you ask us to draw distinctions. You know very well that interbreeding did take place and did produce fertile offspring, and your nitpicking here is way off topic. I said "Neanderthals were human, they interbred with us." Stu could have asked for a clarification, but he did'nt. Presumably you also know ...Nevermind, I am not going to take you seriously. Stu can read biological species concept if he's interested. μηδείς (talk) 18:35, 17 November 2014 (UTC)

- Sure, there is a gray area. But given ligers and wholopins and tomacco (nicotine-overdose danger tomatoes(!), "can interbreed (ever)" seems too generous for a useful concept. "(50%/number of matings in a male's life (unpremature death, to satiety)) of inter-group matings with nubile females at random point in menstrual cycle produce 1 fertile offspring" through "has half the rate of fertile offspring as intra-group matings" seems like a more useful gray zone. Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 20:24, 17 November 2014 (UTC)

- Unless your point is that Neanderthals were apes, you're arguing OR about a dead population, so we can't run any experiments, SMW. But we can say that there's more Neanderthal blood out there now than there ever was when they were a distinct population, since at a low estimated end of 2% of the extra-African genome, that's the equivalent of 100,000,000 descendants, easily. See this comparison of Homo sapiens neanderthalensis, and Homo sapiens sapiens. μηδείς (talk) 20:39, 17 November 2014 (UTC)

- Sure, there is a gray area. But given ligers and wholopins and tomacco (nicotine-overdose danger tomatoes(!), "can interbreed (ever)" seems too generous for a useful concept. "(50%/number of matings in a male's life (unpremature death, to satiety)) of inter-group matings with nubile females at random point in menstrual cycle produce 1 fertile offspring" through "has half the rate of fertile offspring as intra-group matings" seems like a more useful gray zone. Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 20:24, 17 November 2014 (UTC)

- You contradict yourself. You say a binary distinction is arbitrary, and then you ask us to draw distinctions. You know very well that interbreeding did take place and did produce fertile offspring, and your nitpicking here is way off topic. I said "Neanderthals were human, they interbred with us." Stu could have asked for a clarification, but he did'nt. Presumably you also know ...Nevermind, I am not going to take you seriously. Stu can read biological species concept if he's interested. μηδείς (talk) 18:35, 17 November 2014 (UTC)

- The original question was how many of the individual bones could be identified as human - clearly, identifying a set if you know they all belong together is easier. Dealing with adult specimens makes it simpler though - if you don't know the age, the size may not help much, and the differences between species tend to become more apparent with age. AndyTheGrump (talk) 19:56, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

- Neanderthals were human, they interbred with us. The premise is a full set of adult male bones, so the skull alone is the end of the story. Even comparing the femur and the pelvis is enough to draw an instant conclusion. Once you've found a heel the quiz is over. μηδείς (talk) 19:43, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

Dowel action

What is dowel action on a concrete bean in very simple terms? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 194.66.246.59 (talk • contribs)

- It is a "beam", not a "bean". Dowel action is the shear resisted by the reinforcement of the concrete.

- We have articles on beam_(structure) and reinforced concrete and rebar and shear strength. Here are a few slides that explain dowel action with illustrations Also, please sign your posts with four tildes, like this ~~~~ SemanticMantis (talk) 22:03, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

November 15

Questions about Coenzyme A

- Why is it seemingly so rare as a dietary supplement?

- Do you find any theoretical reason in the claim CoA supplementation increase Lipolysis in some rare cases of "low" lipolysis in compare to "high" Glycolysis (Please, take your time to handle this question and try not to be too much skeptic or general in your answer), Thanks to all the helpers. Ben-Natan (talk) 09:32, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

- Humans, like all animals, can synthesize their own Coenzyme-A. As a result, it is very rare to be considered deficient in CoA except in cases of severe malnutrition. In addition, CoA does not handle digestion well, so most of the CoA that you eat (or attempt to consume as supplements) will usually be broken down into smaller molecules before entering the blood. Given that, most of the time people choose to supplement with precursor molecules, such as vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid) or panthenol, which the body knows how to turn into CoA rather than supplement with CoA directly. Dragons flight (talk) 18:38, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

November 16

Width of gas lines.

I was running some gas lines for a unit heater i bought and the manual said i needed larger diameter pipe run depending on the distance the pipe was traveling.

I assume this is to keep a steady pressure, but the pipes throttle at the beginning and the end to a much smaller diameter, so i would think that the throttling would bottleneck the system no matter if i increased the pipe diameter AFTER the throttle.

but apparently it doesn't matter. Why exactly do i need larger diameter piping if i'm going a larger distance? how does an increase of diameter allow for an increase of flow rate? and why does it not matter if there is a reducer on either ends of the pipe?

70.210.70.252 (talk) 02:37, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

- Same thing happens with electricity. Longer extension cords need to be heavier gauge wire for the same load. Pipes exhibit resistance to flow based on their diameter AND length. For short runs the differences can be miniscule, but natural gas pressure in household lines is measured in ounces, so even tiny differences can affect the flow rate. 50.126.104.156 (talk) 04:11, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

Rosetta Orbital Period

Since the comet has such low gravity, will Rosetta be able to maintain a conventional orbit around the comet? If so, how long will that orbital period be? I am guesstimating about a day (24 hours). Altitude 3 miles, orbital path 20+ miles, escape velocity 1 MPH. 50.126.104.156 (talk) 04:05, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

- I believe that Rosetta isn't in a 'free' orbit. It does several powered 'turns' in each orbit (I think, every 60 degrees). So, in effect, it's flying a bunch of nearly straight lines at much higher than escape velocity. I read someplace that Rosetta's speed relative to the comet is about 25 meters/second (sorry, I don't remember where I saw that). According to our article, the orbital distance is 29km (roughly) - although at times, they've reduced that to as little as 10km and started out at 100km. If the orbit was circular, then the circumference of that orbit is 2 pi x 29000 meters, which is around 200,000 meters. At 25 m/sec we get an orbital period of around 7000 seconds...around 2 hours. For a more exact answer, we'd need more details about the shape of the orbit and the fuel burns to keep it like that. When it was out further from the comet, I believe the 'natural' orbit was 26 days.

- An orbit that long would be useless while interacting with the lander because there would be periods of many days when they'd be unable to communicate. Hence the powered turns. SteveBaker (talk) 15:45, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

Signals from UFOs

If there as many UFOs out there as people would have us believe, why dont we pick up some electromagnetic signals from them via, for instance, the SETI program? Also, if UFOs exist, what do they want?--86.182.54.46 (talk) 13:13, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

- We don't hear little green men talking on their walkie-talkies because they are not here. There is almost certainly life out there somewhere (it being a big galaxy and an even bigger universe), but there is no reliable evidence that we are being visited. Alien UFOs, the Bermuda Triangle, the Loch Ness Monster, and ghosts are all more cultural phenomenon than they are scientific ones. Do you want to believe? -- ToE 14:29, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

- There are a few scientists who have theorized that there may not be any complex life anywhere else in the Milky Way, based on extremely low values in the Drake equation. I am aware of one that said that the merger of the mitochondrion with the prokaryote was an extremely unlikely event. Other, more commonly theorized values for the factors in the Drake equation compute the likelihood that there is life elsewhere in the Milky Way, but not within communicating distance. Remember that the Milky Way is an astronomically large place. If relativity is correct and the speed of light is invariant, then there are limits to how far intelligent beings, even long-lived ones, would travel. Even if superluminal travel is possible, the Milky Way is still an astronomically large place. Robert McClenon (talk) 21:25, 17 November 2014 (UTC)

- As to whether UFOs are a cultural phenomenon, Carol Sagan has theorized that there is something about humans, maybe even in brain wiring, so that humans want there to be other beings with whom we can communicate. In the past, this desire resulted in various sorts of folkloric humanoids such as, in European culture, dwarves, trolls, and elves, having other names in other cultures. In modern times, they are extraterrestrials. So maybe they are both a cultural phenomenon and a psychological phenomenon. Robert McClenon (talk) 21:30, 17 November 2014 (UTC)

- If by "UOFs" you were not referring to aliens sighted visiting Earth but instead you were speaking metaphorically of extraterrestrial intelligence in general, and your question was why SETI has not been successful to date, then you should make that clear. -- ToE 14:42, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

- Upper atmosphere objects. Do YOU believe these? ]--86.182.54.46 (talk) 14:47, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

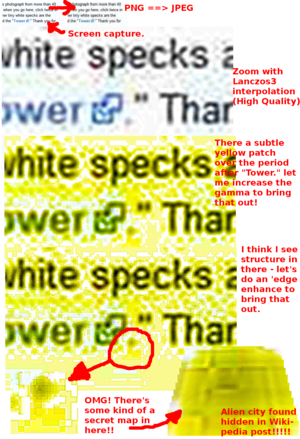

- There is a large community of people out there who take NASA imagery and "enhance" it. Sadly, because they are unschooled in how to do image enhancement correctly, they make stupid mistakes and generate 'artifacts' that look just like UFOs or alien cities or whatever their fevered imaginations can come up with. My favorite way to demonstrate that is this from a post I did here back in 2009 were I take the period at the end of the original question and 'enhance' it until there is a really clear picture of an alien city, complete with buildings, streets and shadows that are convincingly cast by those buildings! I use it so much, I made a copy on my own website:

- I've seen photos of UFO's that were the result of this exact same thing. A tiny white speck in an image (could be dust on a lens, or a star or something) get "enhanced" until you get a nice blurry image that looks just like a classic UFO.

- SteveBaker (talk) 15:17, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

- Aliens are bound by the same laws of physics that we are. Getting from wherever they live to us would take hundreds to thousands of years - and they'd have been unlikely to detect our civilization hundreds or thousands of years ago. It's unlikely that they'd even be able to detect that we're here. With our present technology, we'd be unable to detect a human-scale civilization orbiting a star more than a couple of lightyears away. So:

- "If there as many UFOs out there as people would have us believe"...well that number would be zero...assuming you're listening to people who have seriously thought about it!

- "if UFOs exist, what do they want?"...they don't exist, so the question is moot.

- If you really want an answer to the hypothetical question of what it would be like if they DID exist, then I suppose the chain of reasoning is something like:

- Aliens are bound by the same laws of physics that we are. Getting from wherever they live to us would take hundreds to thousands of years - and they'd have been unlikely to detect our civilization hundreds or thousands of years ago. It's unlikely that they'd even be able to detect that we're here. With our present technology, we'd be unable to detect a human-scale civilization orbiting a star more than a couple of lightyears away. So:

- If they could get here at all, they'd have to have some pretty amazing technology.

- If they wanted to destroy us, and they are that advanced, they could easily do before we ever knew they were there. If they were prepared to spend hundreds of years patiently getting here, they could spend 50 more years to gently deflect a dinosaur-extinction-event sized asteroid to wipe us all out...and we'd never even know they'd done it until we were all dead. So, clearly that's not what they want.

- If they wanted us to detect them, they could very easily make themselves known by any number of impressive and undeniable ways - and they clearly haven't done that either.

- So they must want to remain hidden and so they certainly wouldn't go around broadcasting radio signals that they know we can detect.

- Ergo, if they exist at all, we're unlikely to be able to detect them.

- If there were UFO's in orbit around the earth, they might communicate with each other using lasers or some other sort of directed signal that avoided splattering light or radio in all directions. They'd undoubtedly use stealth technology that would prevent us from picking them up with radar or other such tricks.

- SETI goes to a lot of trouble to eliminate signals that are too close to earth to be a signal from another star system - so even if they could pick up UFO's, they'd be actively ignoring them...but there are lots of other people out there who track space debris and look for unusual satellite activity from potential (human) enemies who could detect an easily-detected alien ship.

- What do they (hypothetically) want? Who knows? We can't detect them.

- A species that's capable of all of this wouldn't be dumb enough to show themselves to people by abducting them, doing experiments on them and letting them go afterwards...if they were trying to keep themselves hidden, they're doing a really terrible job of doing that.

- All of these sad people with nothing better to do in their lives than make up stories are feeding you bullshit...and until a UFO lands on the Whitehouse lawn...we can probably ignore these reports. People are endlessly capable of deluding themselves and going out and making up a pack of lies to make themselves feel more important...it's a part of human nature.

- SteveBaker (talk) 15:02, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

- And Steve has only shown one of many types of image distortion only caused by a specific conversion artifact of the JPEG image compression algorithm. There are many, many other image artifacts that can be caused by camera optics, digital sensors, and all kinds of other complicated software processing, all of which are omnipresent on today's digital cameras! If one is looking for noise, noise is easy to find! Nimur (talk) 16:12, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, exactly. In my example, in addition to the JPEG compression artifacts, I also had our hypothetical UFO investigator use an "Edge enhance" function - which is great at highlighting edges at normal pixel sizes - but when you enlarge the image, you get dark and light fringes along all the edges - which make just dandy fake shadows. I've seen dozens of supposed alien vehicles and buildings that had inadvertently been created from nothing more than edge enhancement and subsequent magnification. SteveBaker (talk) 23:32, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

- And Steve has only shown one of many types of image distortion only caused by a specific conversion artifact of the JPEG image compression algorithm. There are many, many other image artifacts that can be caused by camera optics, digital sensors, and all kinds of other complicated software processing, all of which are omnipresent on today's digital cameras! If one is looking for noise, noise is easy to find! Nimur (talk) 16:12, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

- SteveBaker (talk) 15:02, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

- As far as why an alien species might come to Earth and yet remain hidden, the obvious answer is for scientific study of Earth life, while following a version of the noninterference directive. Earth scientists would absolutely love to find any extraterrestrial life to study, even if it was only as complex as a virus or bacterium. StuRat (talk) 15:16, 16 November 2014 (UTC)