| Revision as of 02:04, 19 December 2014 editMaterialscientist (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Autopatrolled, Checkusers, Administrators1,994,296 editsm Reverted edits by 105.201.15.34 (talk) to last version by Vsmith← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:02, 29 January 2015 edit undoKrelcoyne (talk | contribs)70 editsm →External linksNext edit → | ||

| Line 107: | Line 107: | ||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| * from the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory | |||

| * from MiniScience.com | * from MiniScience.com | ||

| * , an animation | * , an animation | ||

Revision as of 19:02, 29 January 2015

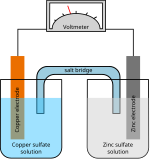

A galvanic cell, or voltaic cell, named after Luigi Galvani, or Alessandro Volta respectively, is an electrochemical cell that derives electrical energy from spontaneous redox reactions taking place within the cell. It generally consists of two different metals connected by a salt bridge, or individual half-cells separated by a porous membrane.

Volta was the inventor of the voltaic pile, the first electrical battery. In common usage, the word "battery" has come to include a single galvanic cell, but a battery properly consists of multiple cells.

History

In 1780, Luigi Galvani discovered that when two different metals (e.g., copper and zinc) are connected and then both touched at the same time to two different parts of a nerve of a frog leg, then the leg contracts. He called this "animal electricity". The voltaic pile, invented by Alessandro Volta in the 1800s, consists of a pile of cells similar to the galvanic cell. However, Volta built it entirely out of non-biological material in order to challenge Galvani's (and the later experimenter Leopoldo Nobili) animal electricity theory in favour of his own metal-metal contact electricity theory. Carlo Matteucci in his turn constructed a battery entirely out of biological material in answer to Volta. These discoveries paved the way for electrical batteries; Volta's cell was named an IEEE Milestone in 1999.

It was suggested by Wilhelm König in 1940 that the object known as the Baghdad battery might represent galvanic cell technology from ancient Parthia. Replicas filled with citric acid or grape juice have been shown to produce a voltage. However, it is far from certain that this was its purpose—other scholars have pointed out that it is very similar to vessels known to have been used for storing parchment scrolls.

Description

In its simplest form, a half-cell consists of a solid metal (called an electrode) that is submerged in a solution; the solution contains cations of the electrode metal and anions to balance the charge of the cations. In essence, a half-cell contains a metal in two oxidation states; inside an isolated half-cell, there is an oxidation-reduction (redox) reaction that is in chemical equilibrium, a condition written symbolically as follows (here, "M" represents a metal cation, an atom that has a charge imbalance due to the loss of "n" electrons):

- M (oxidized species) + ne ⇌ M (reduced species)

A galvanic cell consists of two half-cells, such that the electrode of one half-cell is composed of metal A, and the electrode of the other half-cell is composed of metal B; the redox reactions for the two separate half-cells are thus:

- A + ne ⇌ A

- B + me ⇌ B

In general, then, these two metals can react with each other:

- m A + n B ⇌ n B + m A

In other words, the metal atoms of one half-cell are able to induce reduction of the metal cations of the other half-cell; conversely stated, the metal cations of one half-cell are able to oxidize the metal atoms of the other half-cell. When metal B has a greater electronegativity than metal A, then metal B tends to steal electrons from metal A (that is, metal B tends to oxidize metal A), thus favoring one direction of the reaction:

- m A + n B n B + m A

This reaction between the metals can be controlled in a way that allows for doing useful work:

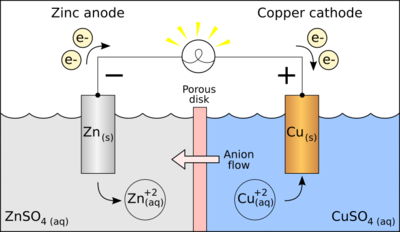

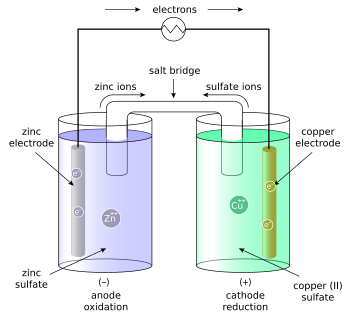

- The electrodes are connected with a metal wire in order to conduct the electrons that participate in the reaction.

- In one half-cell, dissolved metal-B cations combine with the free electrons that are available at the interface between the solution and the metal-B electrode; these cations are thereby neutralized, causing them to precipitate from solution as deposits on the metal-B electrode, a process known as plating.

- This reduction reaction causes the free electrons throughout the metal-B electrode, the wire, and the metal-A electrode to be pulled into the metal-B electrode. Consequently, electrons are wrestled away from some of the atoms of the metal-A electrode, as though the metal-B cations were reacting directly with them; those metal-A atoms become cations that dissolve into the surrounding solution.

- As this reaction continues, the half-cell with the metal-A electrode develops a positively charged solution (because the metal-A cations dissolve into it), while the other half-cell develops a negatively charged solution (because the metal-B cations precipitate out of it, leaving behind the anions); unabated, this imbalance in charge would stop the reaction.

- The solutions are connected by a salt bridge or a porous plate in order to conduct the ions (both the metal-A cations from one solution, and the anions from the other solution), which balances the charges of the solutions and thereby allows the reaction between metal A and metal B to continue without opposition.

By definition:

- The anode is the electrode where oxidation (loss of electrons) takes place; in a galvanic cell, it is the negative electrode, as when oxidation occurs, electrons are left behind on the electrode. These electrons then migrate to the cathode (positive electrode). However, in electrolysis, an electrical current stimulates electron flow in the opposite direction. Thus, the anode is positive, and the statement anode attracts anions is true (negatively charged ions flow to the anode, while electrons are expelled through the wire). The metal-A electrode is the anode.

- The cathode is the electrode where reduction (gain of electrons) takes place; in a galvanic cell, it is the positive electrode, as less oxidation occurs, fewer ions go into solution, and less electrons are left on the electrode. Instead, there is a greater tendency for aqueous ions to be reduced by the incoming electrons from the anode. However, in electrolysis, the charge of the cathode is negative, and attracting positive ions from the solution. In this situation, the statement the cathode attracts cations is true (positively charged, oxidized metal ions flow toward cathode as electrons travel through the wire). The metal-B electrode is the cathode.

Copper readily oxidizes zinc; for the Daniell cell depicted in the figure, the anode is zinc and the cathode is copper, and the anions in the solutions are sulfates of the respective metals. When an electrically conducting device connects the electrodes, the electrochemical reaction is:

- Zn + Cu

→ Zn

+ Cu

The zinc electrode is dissolved and copper is deposited on the copper electrode.

Galvanic cells are typically used as a source of electrical power. By their nature, they produce direct current. The Weston cell has an anode composed of cadmium mercury amalgam, and a cathode composed of pure mercury. The electrolyte is a (saturated) solution of cadmium sulfate. The depolarizer is a paste of mercurous sulfate. When the electrolyte solution is saturated, the voltage of the cell is very reproducible; hence, in 1911, it was adopted as an international standard for voltage.

A battery is a set of galvanic cells that are connected in parallel. For instance, a lead–acid battery has galvanic cells with the anodes composed of lead and cathodes composed of lead dioxide.

Cell voltage

The standard electrical potential of a cell can be determined by use of a standard potential table for the two half cells involved. The first step is to identify the two metals reacting in the cell. Then one looks up the standard electrode potential, E, in volts, for each of the two half reactions. The standard potential for the cell is equal to the more positive E value minus the more negative E value.

For example, in the figure above the solutions are CuSO4 and ZnSO4. Each solution has a corresponding metal strip in it, and a salt bridge or porous disk connecting the two solutions and allowing SO4 ions to flow freely between the copper and zinc solutions. In order to calculate the standard potential one looks up copper and zinc's half reactions and finds:

- Cu + 2

e

⇌ Cu: E = +0.34 V - Zn + 2

e

⇌ Zn: E = −0.76 V

Thus the overall reaction is:

- Cu + Zn ⇌ Cu + Zn

The standard potential for the reaction is then +0.34 V − (−0.76 V) = 1.10 V. The polarity of the cell is determined as follows. Zinc metal is more strongly reducing than copper metal; equivalently, the standard (reduction) potential for zinc is more negative than that of copper. Thus, zinc metal will lose electrons to copper ions and develop a positive electrical charge. The equilibrium constant, K, for the cell is given by

where F is the Faraday constant, R is the gas constant and T is the temperature in kelvins. For the Daniell cell K is approximately equal to 1.5×10. Thus, at equilibrium, a few electrons are transferred, enough to cause the electrodes to be charged.

Actual half-cell potentials must be calculated by using the Nernst equation as the solutes are unlikely to be in their standard states,

where Q is the reaction quotient. This simplifies to

where {M} is the activity of the metal ion in solution. The metal electrode is in its standard state so by definition has unit activity. In practice concentration is used in place of activity. The potential of the whole cell is obtained by combining the potentials for the two half-cells, so it depends on the concentrations of both dissolved metal ions.

The value of 2.303R/F is 0.19845×10 V/K, so at 25 °C (298.15 K) the half-cell potential will change by if the concentration of a metal ion is increased or decreased by a factor of 10.

These calculations are based on the assumption that all chemical reactions are in equilibrium. When a current flows in the circuit, equilibrium conditions are not achieved and the cell potential will usually be reduced by various mechanisms, such as the development of overpotentials. Also, since chemical reactions occur when the cell is producing power, the electrolyte concentrations change and the cell voltage is reduced. A consequence of the temperature dependency of standard potentials is that the voltage produced by a galvanic cell is also temperature dependent.

Galvanic corrosion

Main article: Galvanic corrosionGalvanic corrosion is a process that degrades metals electrochemically. This corrosion occurs when two dissimilar metals are placed in contact with each other in the presence of an electrolyte, such as salt water, forming a galvanic cell. A cell can also be formed if the same metal is exposed to two different concentrations of electrolyte. The resulting electrochemical potential then develops an electric current that electrolytically dissolves the less noble material.

Cell types

See also

- Biological cell voltage

- Bio-nano generator

- Desulfation

- Electrode potential

- Electrosynthesis

- Isotope electrochemistry

- Bioelectrochemical reactor

- Enzymatic biofuel cell

- Electrohydrogenesis

- Electrochemical engineering

- Galvanic series

- Sacrificial anode

References

- "battery" (def. 4b), Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary (2008). Retrieved 6 August 2008.

- Keithley, Joseph F. (1999). Daniell Cell. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 49–51. ISBN 0-7803-1193-0.

- Kipnis, Nahum (2003) "Changing a theory: the case of Volta's contact electricity", Nuova Voltiana, Vol. 5. Università degli studi di Pavia, 2003 ISBN 88-203-3273-6. pp. 144–146

- Clarke, Edwin; Jacyna, L. S. (1992) Nineteenth-Century Origins of Neuroscientific Concepts, University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07879-9. p. 199

- "Milestones:Volta's Electrical Battery Invention, 1799". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- Haughton, Brian (2007) Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries. Career Press. ISBN 1564148971. pp. 129–132

- ^ "An introduction to redox equilibria". Chemguide. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- Atkins, P; de Paula (2006). Physical Chemistry. J. (8th. ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-870072-2. Chapter 7, sections on "Equilibrium electrochemistry"

- Atkins, P; de Paula (2006). Physical Chemistry. J. (8th. ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-870072-2. Section 25.12 "Working Galvanic cells"

External links

- Interactive tutorial on a simple electrical (Galvanic) cell from the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory

- How to build a galvanic cell battery from MiniScience.com

- Galvanic Cell, an animation

- Interactive animation of Galvanic Cell. Chemical Education Research Group, Iowa State University.

n B + m A

n B + m A

if the concentration of a metal ion is increased or decreased by a factor of 10.

if the concentration of a metal ion is increased or decreased by a factor of 10.