| Revision as of 00:24, 1 February 2015 editNdandulalibingi (talk | contribs)998 edits Added content.Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 00:43, 1 February 2015 edit undoNdandulalibingi (talk | contribs)998 edits Added citation.Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web editNext edit → | ||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

| Europeans unfamiliar with the so-called "Ganguela" ethnic groups, but also contemporary urban Angolans often consider them erroneously as "tribes" of the ]. However, they are in fact quite distinct from the Ovimbundu, in terms of language, culture, and social identity. It is true that some of them who live in the immediate neighbourhood of the Ovimbundu. e.g. the Lwimbi and the "Ganguela proper", have to some extension been affected by the "umbundization" that has taken place in the 20th century, on the borders of the original habitat of the Ovimbundu. | Europeans unfamiliar with the so-called "Ganguela" ethnic groups, but also contemporary urban Angolans often consider them erroneously as "tribes" of the ]. However, they are in fact quite distinct from the Ovimbundu, in terms of language, culture, and social identity. It is true that some of them who live in the immediate neighbourhood of the Ovimbundu. e.g. the Lwimbi and the "Ganguela proper", have to some extension been affected by the "umbundization" that has taken place in the 20th century, on the borders of the original habitat of the Ovimbundu. | ||

| The peoples later called "Ganguela" have been known to the Portuguese since the 17th century, when they became involved in the commercial activities developed by the colonial bridgeheads of ] and ] which existed at that time. On the one hand, many of the slaves bought by the Portuguese from African middlemen came from these people.<ref>See Joseph Miller: ''Way of Death: Merchant Capitalism and the Angolan Slave Trade, 1730-1839'', Madison: Wisconsin University Press, 1988</ref> On the other hand, in the 19th and early 20th century the so-called "Ganguela" peoples furnished wax, honey, ivory and others good for the caravan trade organised by the Ovimbundu for the Portuguese in Benguela.<ref>See Hermann Pössinger, ''A transformação da sociedade umbundu desde o colapso do comércio das caravanas'', ''Revista Internacional de Estudos Africanos'' (Lisbon), 4/5, 1986, pp. 75-158</ref> | The peoples later called "Ganguela" have been known to the Portuguese since the 17th century, when they became involved in the commercial activities developed by the colonial bridgeheads of ] and ] which existed at that time. On the one hand, many of the slaves bought by the Portuguese from African middlemen came from these people.<ref>See Joseph Miller: ''Way of Death: Merchant Capitalism and the Angolan Slave Trade, 1730-1839'', Madison: Wisconsin University Press, 1988</ref> On the other hand, in the 19th and early 20th century the so-called "Ganguela" peoples furnished wax, honey, ivory and others good for the caravan trade organised by the Ovimbundu for the Portuguese in Benguela.<ref></ref><ref>See Hermann Pössinger, ''A transformação da sociedade umbundu desde o colapso do comércio das caravanas'', ''Revista Internacional de Estudos Africanos'' (Lisbon), 4/5, 1986, pp. 75-158</ref> | ||

| After the collapse of the caravan trade, the so-called "Ganguela" were for long - in fact until the very end of the colonial period - of little interest for the Portuguese. This is why they were relatively late subjected to a colonial occupation to which - with the exception of the Mbunda - they offered near to no serious resistance.<ref>See René Pélissier: ''Les Guerres grises: Résistance et revoltes en Angola (1845-1941)'', Montamets/Orgeval: Éditions Pélissier, 1977</ref> | After the collapse of the caravan trade, the so-called "Ganguela" were for long - in fact until the very end of the colonial period - of little interest for the Portuguese. This is why they were relatively late subjected to a colonial occupation to which - with the exception of the Mbunda - they offered near to no serious resistance.<ref>See René Pélissier: ''Les Guerres grises: Résistance et revoltes en Angola (1845-1941)'', Montamets/Orgeval: Éditions Pélissier, 1977</ref> | ||

Revision as of 00:43, 1 February 2015

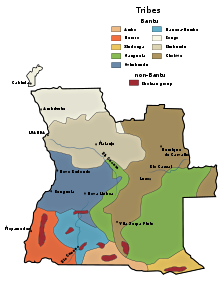

Ganguela (pronunciation: gang'ela) or Nganguela is the name of a small ethnic group living in Angola, but the Ovimbundu call peoples East of their territory "Ovingangela" a derogatory term meaning "useless peoples or worse" and therefore since colonial times the term has been applied to a number of peoples East of the Bié Plateau which include the Lwena (Luena), the Luvale, the Mbunda, the Lwimbi, the Camachi and others.

All of these peoples live on subsistence agriculture, on the upbreeding of small animals, and from gathering wild fruit, honey and other eatable items. Each group have their own language, although these are related among themselves, but Missionary Emil Pearson erroneously created Ngangela language by mixing these languages, which has recently been recognized as one of the six National languages replacing Mbunda language. Each groups also has its own social identity; there exists no overarching social identity encompassing them all, so that one cannot speak of these groups as one people divided into subgroups.

Europeans unfamiliar with the so-called "Ganguela" ethnic groups, but also contemporary urban Angolans often consider them erroneously as "tribes" of the Ovimbundu. However, they are in fact quite distinct from the Ovimbundu, in terms of language, culture, and social identity. It is true that some of them who live in the immediate neighbourhood of the Ovimbundu. e.g. the Lwimbi and the "Ganguela proper", have to some extension been affected by the "umbundization" that has taken place in the 20th century, on the borders of the original habitat of the Ovimbundu.

The peoples later called "Ganguela" have been known to the Portuguese since the 17th century, when they became involved in the commercial activities developed by the colonial bridgeheads of Luanda and Benguela which existed at that time. On the one hand, many of the slaves bought by the Portuguese from African middlemen came from these people. On the other hand, in the 19th and early 20th century the so-called "Ganguela" peoples furnished wax, honey, ivory and others good for the caravan trade organised by the Ovimbundu for the Portuguese in Benguela.

After the collapse of the caravan trade, the so-called "Ganguela" were for long - in fact until the very end of the colonial period - of little interest for the Portuguese. This is why they were relatively late subjected to a colonial occupation to which - with the exception of the Mbunda - they offered near to no serious resistance.

During the few decades under colonial rule, their way of life changed less than in most other regions of Angola. As a rule, they were neither the object of systematic missionary work, nor subject to heavy tax levy or the recruitment as paid labour. The only important economic activity developed by the Portuguese in their area was the production of timber, for factories in Angola or in Portugal.

During the anti-colonial war, 1961–1974, and especially during the Civil War in Angola, some of these groups were affected to a greater or lesser degree, although their active involvement was rather limited. As a consequence, many took refuge in neighbouring Zambia and (to a lesser degree) Namibia. In particular, almost half of the Mbunda settled in Western Zambia, but this people maintains an overall cohesion through their traditional authorities both in Angola and Zambia, and detest being called Ganguela because it has a slightly derogatory meaning when applied by the western ethnic groups,.

References

- Alvin W. Urquhart, Patterns of Settlement and Subsistence in Southwestern Angola, National Academies Press, 1963, p 10.

- For a detailed description see José Redinha, Etnias e culturas de Angola, Luanda: Instituto de Investigação Científica de Angola, 1975

- Robert Papstein, "The Central African Historical Research Project", in Harneit-Sievers, 2002, A Place in the World: New Local Historiographies from Africa and South Asia, p. 178

- Robert Papstein (ed.), The history and cultural life of the Mbunda speaking peoples, Lusaka: Cheke Cultural Writers Association, 1994, ISBN 99 820 3006X

- See Joseph Miller: Way of Death: Merchant Capitalism and the Angolan Slave Trade, 1730-1839, Madison: Wisconsin University Press, 1988

- See Hermann Pössinger, A transformação da sociedade umbundu desde o colapso do comércio das caravanas, Revista Internacional de Estudos Africanos (Lisbon), 4/5, 1986, pp. 75-158

- See René Pélissier: Les Guerres grises: Résistance et revoltes en Angola (1845-1941), Montamets/Orgeval: Éditions Pélissier, 1977

- See Basil Davidson: In the Eye of the Storm: Angola’s People, New York: Doubleday, 1972; Samuel Chiwale, Cruzei-me com a história, Lisbon: Sextante, 2008; Inge Brinkman, A War for People: Civilians, Mobility and Legitimacy in South-East Angola during the MPLA's War for Independence, Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag, 2005

- Alvin W. Urquhart, Patterns of Settlement and Subsistence in Southwestern Angola, National Academies Press, 1963, p 10

- The Mbunda Kingdom Research and Advisory Council

Bibliography

- Hermann Baumann: Die Völker Afrikas und ihre traditionellen Kulturen. Teil 1 Allgemeiner Teil und südliches Afrika, Steiner, Wiesbaden, 1975–1979