| Revision as of 09:03, 9 February 2015 edit115.178.96.74 (talk) →=Explanation← Previous edit | Revision as of 09:04, 9 February 2015 edit undo115.178.96.74 (talk) →=ExplanationNext edit → | ||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

| ==Explanation= | ==Explanation= | ||

| Right ascension is measured from the ] or the ], which is the place on the ] where the ] crosses the ] from south to north at the March ] and is located in the constellation Pisces. Right ascension is measured continuously in a full circle from that equinox towards the east.<ref> | |||

| {{cite book | {{cite book | ||

| |url=http://books.google.com/?id=s_o4AAAAMAAJ | |url=http://books.google.com/?id=s_o4AAAAMAAJ | ||

Revision as of 09:04, 9 February 2015

Right ascension (abbreviated RA; symbol α) is the angular distance measured eastward along the celestial equator from the vernal equinox to the hour circle of the point in question. When combined with declination, these astronomical coordinates specify the direction of a point on the celestial sphere in the equatorial coordinate system.

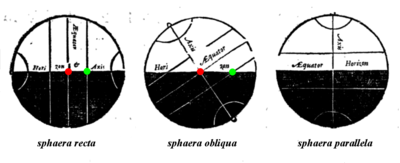

An old term, right ascension (Latin, ascensio recta) refers to the ascension, or the point on the celestial equator which rises with any celestial object, as seen from the Earth's equator, where the celestial equator intersects the horizon at a right angle. It is contrasted with oblique ascension, the point on the celestial equator which rises with a celestial object as seen from almost anywhere else on Earth, where the celestial equator intersects the horizon at an oblique angle.

=Explanation

Moulton, Forest Ray (1916). An Introduction to Astronomy. Macmillan Co., New York. pp. 125–126.; at Google books</ref>

Any units of angular measure could have been chosen for right ascension, but it is customarily measured in hours (), minutes (), and seconds (), with 24 being equivalent to a full circle. Astronomers have chosen this unit to measure right ascension because they measure a star's location by timing its passage through the highest point in the sky as the Earth rotates. The highest point in the sky, called meridian, is the projection of a longitude line onto the celestial sphere. Since a complete circle contains 24 of right ascension or 360 degrees of arc°, 1⁄24 of a circle is measured as 1 of right ascension or 15°; 1⁄(24×60) of a circle is measured as 1 of right ascension or 15 minutes of arc (also written as 15'); and 1⁄(24×60×60) of a circle contains 1 of right ascension or 15 seconds of arc (also written as 15"). A full circle, measured in right ascension units, contains 24×60×60 = 86,400, or 24×60 = 1,440, or 24.

See also: Hour angleBecause right ascensions are measured in hours (of rotation of the Earth), they can be used to time the positions of objects in the sky. For example, if a star with RA = 013000 is on the meridian, then a star with RA = 200000 will be on the meridian 18.5 sidereal hours later.

Sidereal hour angle, used in celestial navigation, is similar to right ascension, but increases westward rather than eastward. Usually measured in degrees ( ° ), it is the complement of right ascension with respect to 24. It is important not to confuse sidereal hour angle with the astronomical concept of hour angle, which measures angular distance of an object westward from the local meridian.

Symbols and abbreviations

| Unit | Value | Symbol | Sexagesimal system | In radians |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hour | 1⁄24 circle | ( ) | 15° | π⁄12 rad |

| Minute | 1⁄60 hour, 1⁄1,440 circle | ( ) | 1⁄4°, 15' | π⁄720 rad |

| Second | 1⁄60 minute, 1⁄3,600 hour, 1⁄86,400 circle | ( ) | 1⁄240°, 1⁄4', 15" | π⁄43200 rad |

Effects of precession

Main article: Axial precessionThe Earth's axis rotates slowly westward about the poles of the ecliptic, completing one circuit in about 26,000 years. This effect, known as precession, causes the coordinates of stationary celestial objects to change continuously, if rather slowly. Therefore, equatorial coordinates (including right ascension) are inherently relative to the year of their observation, and astronomers specify them with reference to a particular year, known as an epoch. Coordinates from different epochs must be mathematically rotated to match each other, or to match a standard epoch.

The currently used standard epoch is J2000.0, which is January 1, 2000 at 12:00 TT. The prefix "J" indicates that it is a Julian epoch. Prior to J2000.0, astronomers used the successive Besselian Epochs B1875.0, B1900.0, and B1950.0.

History

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The concept of right ascension has been known at least as far back as Hipparchus who measured stars in equatorial coordinates in the 2nd century BC. But Hipparchus and his successors made their star catalogs in ecliptic coordinates, and the use of RA was limited to special cases.

With the invention of the telescope, it became possible for astronomers to observe celestial objects in greater detail, provided that the telescope could be kept pointed at the object for a period of time. The easiest way to do that is to use an equatorial mount, which allows the telescope to be aligned with one of its two pivots parallel to the Earth's axis. A motorized clock drive often is used with an equatorial mount to cancel out the Earth's rotation. As the equatorial mount became widely adopted for observation, the equatorial coordinate system, which includes right ascension, was adopted at the same time for simplicity. Equatorial mounts could then be accurately pointed at objects with known right ascension and declination by the use of setting circles. The first star catalog to use right ascension and declination was John Flamsteed's Historia Coelestis Britannica (1712, 1725).

See also

2

Notes and references

- U.S. Naval Observatory Nautical Almanac Office (1992). Seidelmann, P. Kenneth (ed.). Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac. University Science Books, Mill Valley, CA. p. 735. ISBN 0-935702-68-7.

- Bleau, Guilielmi (1668). Institutio Astronomica. p. 65., at Google books, "Ascensio recta Solis, stellæ, aut alterius cujusdam signi, est gradus æquatorus cum quo simul exoritur in sphæra recta"; roughly translated, "Right ascension of the Sun, stars, or any other sign, is the degree of the equator which rises together in a right sphere"

- Lathrop, John (1821). A Compendious Treatise on the Use of Globes and Maps. Wells and Lilly and J.W. Burditt, Boston. pp. 29, 39., at Google books

- Moulton (1916), p. 126.

- Explanatory Supplement (1992), p. 11

- Moulton (1916), pp. 92–95.

-

see, for instance,

U.S. Naval Observatory Nautical Almanac Office; U.K. Hydrographic Office; H.M. Nautical Almanac Office (2008). "Time Scales and Coordinate Systems, 2010". The Astronomical Almanac for the Year 2010. U.S. Govt. Printing Office. p. B2,.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - Bleau (1668), p. 40–41.

External links

- MEASURING THE SKY A Quick Guide to the Celestial Sphere James B. Kaler, University of Illinois

- Celestial Equatorial Coordinate System University of Nebraska-Lincoln

- Celestial Equatorial Coordinate Explorers University of Nebraska-Lincoln

- Merrifield, Michael. "(α,δ) – Right Ascension & Declination". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.