| Revision as of 22:33, 23 February 2015 view sourceOmar-toons (talk | contribs)5,164 edits rv WP:DISRUPT← Previous edit | Revision as of 23:06, 23 February 2015 view source M.Bitton (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users54,653 edits rv patheticNext edit → | ||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

| |strength1= | |strength1= | ||

| |strength2= | |strength2= | ||

| |casualties1=39 killed |

|casualties1=39 killed (Morrocan official count<ref name="Hugues137">Hughes 2001, page 137</ref>) | ||

| |casualties2=69 killed and 250 wounded<ref>Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia], Volume 1, edited by Alexander Mikaberidze, page 797</ref><br /> | |||

| About 300 killed (Estimate<ref name="Hugues137"/>) | |||

| |notes= | |notes= | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| Line 42: | Line 43: | ||

| ==War== | ==War== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Skirmishes along the border eventually escalated into a full-blown confrontation, with intense fighting around the oasis towns of ] and ]. The ], recently formed from the ] ranks of the FLN's ] (ALN) was still geared towards ], and had little heavy equipment.<ref> – themilitant.com</ref> They were still battle-ready and had tens of thousands of experienced veterans, and strengthening the armed forces had been a top priority for the military-dominated post-war government. On the other hand, while the modern, western-equipped Moroccan army (France was the bigger arms seller to Morocco at that time) was superior on the battlefield,<ref name="countrystudies" /><ref> – Onwar.com</ref> it did not manage to penetrate into Algeria. The Algerians had counted on hit-and-run attacks as their main strategy, but the Moroccans managed to counter this approach. The Moroccans built ] ]. These Sand Walls had land mines and electronic warning systems, as well as strong defenses placed by the Moroccan troops. The tactic was later used in the ]. |

Skirmishes along the border eventually escalated into a full-blown confrontation, with intense fighting around the oasis towns of ] and ]. The ], recently formed from the ] ranks of the FLN's ] (ALN) was still geared towards ], and had little heavy equipment.<ref> – themilitant.com</ref> They were still battle-ready and had tens of thousands of experienced veterans, and strengthening the armed forces had been a top priority for the military-dominated post-war government. On the other hand, while the modern, western-equipped Moroccan army (France was the bigger arms seller to Morocco at that time) was superior on the battlefield,<ref name="countrystudies" /><ref> – Onwar.com</ref> it did not manage to penetrate into Algeria. The Algerians had counted on hit-and-run attacks as their main strategy, but the Moroccans managed to counter this approach. The Moroccans built ] ]. These Sand Walls had land mines and electronic warning systems, as well as strong defenses placed by the Moroccan troops. The tactic was later used in the ]. After hundreds of casualties on both sides,<ref>A History of Modern Morocco, Susan Gilson Miller, page 166</ref> the war reached a stalemate and after the intervention of the ] (OAU) and the ], it was broken off after approximately three weeks. The OAU eventually managed to arrange a formal cease-fire on February 20, 1964.<ref> – Arabworld.nitle.org</ref> A ] was then reached after ] mediation, and a ] instituted but hostilities simmered. | ||

| ==Results== | ==Results== | ||

| Line 48: | Line 49: | ||

| The governments of both Morocco and Algeria used the war to describe ] movements as unpatriotic. The Moroccan ] and the Algerian-Berber ] of ] both suffered as a result of this. In the case of UNFP, its leader, ], sided with Algeria, and was sentenced to ] '']'' as a result. In Algeria, the armed rebellion of the FFS in Kabylie fizzled out, as commanders defected to join the national forces against Morocco. | The governments of both Morocco and Algeria used the war to describe ] movements as unpatriotic. The Moroccan ] and the Algerian-Berber ] of ] both suffered as a result of this. In the case of UNFP, its leader, ], sided with Algeria, and was sentenced to ] '']'' as a result. In Algeria, the armed rebellion of the FFS in Kabylie fizzled out, as commanders defected to join the national forces against Morocco. | ||

| Many have argued that the Sand War and its bitter legacy was a factor in the attitude of Algeria towards the conflict in ] in the 1970s. In 1975, Morocco took control of this territory, now known as ], while Algeria began backing politically and militarily an ]-minded ] ] organization, the ]. | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 23:06, 23 February 2015

Not to be confused with war sand.| Sand War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Combat support (Discrete): |

Combat support: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 39 killed (Morrocan official count) |

69 killed and 250 wounded | ||||||

| Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Morocco |

|

| Prehistory |

|

Classical to Late Antiquity (8th century BC – 7th century AD) |

|

Early Islamic (8th–10th century AD) |

|

Territorial fragmentation (10th–11th century AD) |

|

Empire (beginning 11th century AD) other political entities |

|

Decline (beginning 19th century AD) |

|

Protectorate (1912–56) |

|

Modern (1956–present) |

Related topics

|

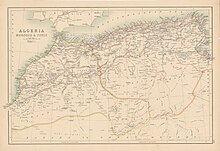

The Sand War or Sands War occurred along the Algerian-Moroccan border in October 1963, and was a Moroccan attempt to claim the Tindouf and the Béchar areas that France had annexed to French Algeria a few decades earlier.

Background

Three factors contributed to the outbreak of this conflict: the absence of a precise delineation of the border between Algeria and Morocco, the discovery of important mineral resources in the disputed area, and the Moroccan irredentism fueled by the Greater Morocco ideology of the Istiqlal Party and Allal al-Fassi.

Before French colonization of the region in the nineteenth century, part of south and west Algeria were under Moroccan influence and no border was defined. In the Treaty of Lalla Maghnia (March 18, 1845), which set the border between French Algeria and Morocco, it is stipulated that "a territory without water is uninhabitable and its boundaries are superfluous" the border is delineated over only 165 km. Beyond that there is only one border area, without limit, punctuated by tribal territories attached to Morocco or Algeria.

In the 1890s, the French administration and military called for the annexation of the Touat, the Gourara and the Tidikelt, a complex that had been part of the Moroccan Empire for many centuries prior to the arrival of the French in Algeria.

An armed conflict opposed French 19th Corps Oran and Algiers divisions to the Aït Khabbash, a fraction of the Aït Ounbgui khams of the Aït Atta confederation. The conflict ended by the annexation of the Touat-Gourara-Tidikelt complex by France in 1901.

After Morocco became a French protectorate in 1912, the French administration set borders between the two territories, but these tracks were often misidentified (Varnier line in 1912, Trinquet line in 1938), and varied from one map to another, since for the French administration these were not international borders and the area was virtually uninhabited. The discovery of large deposits of oil and minerals (iron, manganese) in the region led France to define more precisely the territories, and in 1952 the French decided to integrate Tindouf and Colomb-Bechar to the French departments of Algeria.

The last bloody years of the FLN's rebellion had been fought essentially to prevent France from splitting the Sahara regions from the emerging Algerian state, and thus neither Ben Bella nor the rest of the wartime FLN were inclined to give them up to Morocco when independence was achieved. The Algerians therefore did not recognize Morocco's historical or political claims of Greater Morocco that includes Bechar and Tindouf Province. Instead, they perceived the Moroccan demands as an attempt to infringe the country's hard-won independence and pressure it when it was at its weakest. Algeria was still reeling from the enormous damage caused by the Algerian War, and the government scarcely held control over its entire territory: significantly, a Berber anti-FLN rebellion under the leadership of Hocine Aït Ahmed had recently flared up in the Kabyle mountains. Tension escalated as neither side wanted to back down.

War

Skirmishes along the border eventually escalated into a full-blown confrontation, with intense fighting around the oasis towns of Tindouf and Figuig. The Algerian army, recently formed from the guerrilla ranks of the FLN's Armée de Libération Nationale (ALN) was still geared towards asymmetric warfare, and had little heavy equipment. They were still battle-ready and had tens of thousands of experienced veterans, and strengthening the armed forces had been a top priority for the military-dominated post-war government. On the other hand, while the modern, western-equipped Moroccan army (France was the bigger arms seller to Morocco at that time) was superior on the battlefield, it did not manage to penetrate into Algeria. The Algerians had counted on hit-and-run attacks as their main strategy, but the Moroccans managed to counter this approach. The Moroccans built fortified Sand Walls. These Sand Walls had land mines and electronic warning systems, as well as strong defenses placed by the Moroccan troops. The tactic was later used in the Western Sahara War. After hundreds of casualties on both sides, the war reached a stalemate and after the intervention of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) and the Arab League, it was broken off after approximately three weeks. The OAU eventually managed to arrange a formal cease-fire on February 20, 1964. A peace agreement was then reached after Arab League mediation, and a demilitarized zone instituted but hostilities simmered.

Results

The Sand War laid the foundations for a lasting and often intensely hostile rivalry between Morocco and Algeria, exacerbated by the differences in political outlook between the conservative Moroccan monarchy and the revolutionary, Arab nationalist Algerian military government. Final border demarcation in the Tindouf area was not reached until many years later, in a negotiation process stretching from 1969 to 1972, with Algeria offering Morocco shares in the iron ore earnings from Tindouf for recognition of its borders.

The governments of both Morocco and Algeria used the war to describe opposition movements as unpatriotic. The Moroccan UNFP and the Algerian-Berber FFS of Aït Ahmed both suffered as a result of this. In the case of UNFP, its leader, Mehdi Ben Barka, sided with Algeria, and was sentenced to death in absentia as a result. In Algeria, the armed rebellion of the FFS in Kabylie fizzled out, as commanders defected to join the national forces against Morocco.

See also

References

- ^ Ottaway 1970, pp. 166

- ^ Hughes 2001, page 137

- Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia], Volume 1, edited by Alexander Mikaberidze, page 797

- ^ Touval 1967, p. 106.

- Biography of Allal al-Fassi

- ^ Security Problems with Neighboring States – Countrystudies.us

- Article 6 du traité, cité par Zartman, page 163

- Reyner 1963, p. 316.

- Frank E. Trout, Morocco's Boundary in the Guir-Zousfana River Basin, in: African Historical Studies, Vol. 3, No. 1 (1970), pp. 37–56, Publ. Boston University African Studies Center: « The Algerian-Moroccan conflict can be said to have begun in 1890s when the administration and military in Algeria called for annexation of the Touat-Gourara-Tidikelt, a sizable expanse of Saharan oases that was nominally a part of the Moroccan Empire (...) The Touat-Gourara-Tidikelt oases had been an appendage of the Moroccan Empire, jutting southeast for about 750 kilometers into the Saharan desert »

- Frank E. Trout, Morocco's Saharan Frontiers, Droz (1969), p.24 (ISBN 9782600044950) : « The Gourara-Touat-Tidikelt complex had been under Moroccan domination for many centuries prior to the arrival of the French in Algeria »

- Claude Lefébure, Ayt Khebbach, impasse sud-est. L'involution d'une tribu marocaine exclue du Sahara, in: Revue de l'Occident musulman et de la Méditerranée, N°41–42, 1986. Désert et montagne au Maghreb. pp. 136–157: « les Divisions d'Oran et d'Alger du 19e Corps d'armée n'ont pu conquérir le Touat et le Gourara qu'au prix de durs combats menés contre les semi-nomades d'obédience marocaine qui, depuis plus d'un siècle, imposaient leur protection aux oasiens »

- Reyner 1963, p. 317.

- Heggoy 1970.

- Farsoun & Paul 1976, p. 13.

- How Cuba aided revolutionary Algeria in 1963 – themilitant.com

- Armed Conflict Events Data – Onwar.com

- A History of Modern Morocco, Susan Gilson Miller, page 166

- The 1963 border war and the 1972 treaty – Arabworld.nitle.org

- Algiers and Rabat, still miles apart – Le Monde Diplomatique

Bibliography

- Farsoun, K.; Paul, J. (1976), "War in the Sahara: 1963", Middle East Research and Information Project (MERIP) Reports, 45: 13–16, JSTOR 3011767. Link requires subscription to Jstor.

- Heggoy, A.A. (1970), "Colonial origins of the Algerian-Moroccan border conflict of October 1963", African Studies Review, 13 (1): 17–22, JSTOR 523680. Link requires subscription to Jstor.

- Ottaway, David (1970), Algeria: The Politics of a Socialist Revolution, Berkeley, California: University of California Press, ISBN 9780520016552

- Reyner, A.S. (1963), "Morocco's international boundaries: a factual background", Journal of Modern African Studies, 1 (3): 313–326, doi:10.1017/s0022278x00001725, JSTOR 158912. Link requires subscription to Jstor.

- Torres-García, Ana (2013), "US diplomacy and the North African 'War of the Sands' (1963)", The Journal of North African Studies, 18 (2): 324–48, doi:10.1080/13629387.2013.767041

- Touval, S. (1967), "The Organization of African Unity and African borders", International Organization, 21 (1): 102–127, doi:10.1017/s0020818300013151, JSTOR 2705705. Link requires subscription to Jstor.

- Stephen O. Hughes, Morocco under King Hassan, Garnet & Ithaca Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8637-2285-7

Further reading

- Pennell, C.R. (2000). Morocco Since 1830. A History. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-6676-5.

- Stora, B. (2004). Algeria 1830–2000. A Short History. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-3715-6.