| Revision as of 16:07, 21 May 2015 edit199.167.103.222 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 16:07, 21 May 2015 edit undo173.209.211.146 (talk)No edit summaryTags: Mobile edit Mobile web editNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{For|the James L. Brooks motion picture|Spanglish (film)}} | |||

| '''Spanglish''' is formed by the interaction between ], a ], and ], a ] language, in the speeches of people who speak both languages or parts of both languages. Spanglish is genetically unrelated to any other language because it is not a language itself, but rather an overlapping and mixing of Spanish and EnglishNiggerNiggerNigger ]s and ]. | |||

| Spanglish is not a ], because unlike pidgin languages, Spanglish has a linguistic history that is traceable. Spanglish can be a variety of Spanish with heavy usage of English or a variety of English with heavy usage of Spanish. It can either be more related to Spanish or English depending on the circumstances of the individual or people. | |||

| The term Spanglish was first brought into literature by the Puerto Rican ] in the late 1940s, when he called it "Espanglish".<ref>{{cite web|website=http://repeatingislands.com/2011/11/15/salvador-tio%E2%80%99s-100th-anniversary/}}</ref> | |||

| ==History and distribution== | ==History and distribution== | ||

| In the late 1940s, the Puerto Rican linguist ] coined the terms ''Spanglish'' (for Spanish spoken with some English terms) and the less commonly used ''Inglañol'' (for English spoken with some Spanish terms). | In the late 1940s, the Puerto Rican linguist ] coined the terms ''Spanglish'' (for Spanish spoken with some English terms) and the less commonly used ''Inglañol'' (for English spoken with some Spanish terms). | ||

Revision as of 16:07, 21 May 2015

History and distribution

In the late 1940s, the Puerto Rican linguist Salvador Tió coined the terms Spanglish (for Spanish spoken with some English terms) and the less commonly used Inglañol (for English spoken with some Spanish terms).

Spanglish is common in the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico as the United States Army and the early colonial administration tried to impose the English language on island residents. Between 1902 and 1948, the main language of instruction in public schools (used for all subjects except Spanish language courses) was English. Actually, Puerto Rico is unique in having both English and Spanish as its official languages. Consequently, many American English words are now found in the Puerto Rican vocabulary. Spanglish may also be known by a regional name.

Spanglish does not have one unified dialect and therefore lacks uniformity—specifically, Spanglish spoken in New York, Miami, Texas, and California can be different. Although not always uniform, Spanglish is so popular in many Spanish-speaking communities in the United States, especially in the Miami Hispanic community, that some knowledge of Spanglish is required to understand those in the area. It is common in Panama, where the 96-year (1903–1999) U.S. control of the Panama Canal influenced much of local society, especially among the former residents of the Panama Canal Zone, the Zonians. Some version of Spanglish, whether by that name or another, is likely to be used wherever speakers of both languages mix.

Many Puerto Ricans living on the island of St. Croix speak in informal situations a unique Spanglish-like combination of Puerto Rican Spanish and the local Crucian dialect, which is very different from the Spanglish spoken elsewhere. The same assumption goes for the large Puerto Rican population in the state of New York and Boston.

Spanglish is found commonly in the modern United States, reflecting the growing Hispanic-American demographic due to immigration. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the population of Hispanics grew from 35.3 million to 53 million between 2000 and 2012. This larger Hispanic Demographic reflects the largest American minority, with a large portion being of Mexican descent. The Mexican community is one of the fastest growing groups, increasing from 20.6 million to 34.5 million between 2000 and 2012. Around 58% of this community chose California, especially Southern California, as their new home. Spanglish usage is found widely throughout the heavily Mexican-American and Hispanic-American communities of Southern California. The usage of Spanglish and understanding of it, has become of vital importance to members of communities in largely influenced areas such as Miami, New York, Texas, and California. In Miami, for example, they have their own similar form of Spanglish that many colloquially term 'Cubonics.'

Usage

Spanglish patterns

Spanglish is informal and lacks documented structure and rules, although speakers can consistently judge the grammaticality of a phrase or sentence. From a linguistic point of view, Spanglish often is mistakenly labeled many things. Spanglish is not a creole or dialect of Spanish, because although people claim to be native speakers of Spanglish, Spanglish itself is not a language on its own, but speakers speak English or Spanish with a heavy influence from the other language. The definition of Spanglish has been unclearly explained by scholars and linguists despite being noted so often. Spanglish is the fluid exchange of language between English and Spanish, present in the heavy influence in the words and phrases used by the speaker. Spanglish is currently considered a hybrid language by linguists—many actually refer to Spanglish as "Spanish-English code-switching", though there is some influence of borrowing, and lexical and grammatical shifts as well.

The inception of Spanglish is due to the influx of Latin American people into North America, specifically the United States of America. As mentioned previously, the phenomenon of Spanglish can be separated into two different categories: code switching or borrowing, and lexical and grammatical shifts. For example, a fluent bilingual speaker addressing another bilingual speaker might engage in code switching with the sentence, "I'm sorry I cannot attend next week's meeting porque tengo una obligación de negocios en Boston, pero espero que I'll be back for the meeting the week after"—which means, "I'm sorry I cannot attend next week's meeting because I have a business obligation in Boston, but I hope to be back for the meeting the week after."

Calques

Calques are translations of entire words or phrases from one language into another. They represent the simplest forms of Spanglish, as they undergo no lexical or grammatical structural change. The usage of calques is common throughout most languages, evident in the calques of Arabic exclamations used in Spanish.

Examples:

- "To call back" → “llamar pa´trás”

- "It's up to you." → “está p´arriba de ti”

- "To run for governor" → “correr para gobernador”

Semantic extensions

Semantic extension or reassignment refers to a phenomenon where speakers of the originating language use a word more similar to that of a second language in place of their own with a similar, or not so similar, meaning. Usually this occurs in the case of false cognates, where similar words are thought to have like meanings based on their cognates. This occurs often between speakers of two languages due to the likeness of the cognates and different meanings among any language.

Examples:

- "Carpeta" in place of "moqueta" or "alfombra" (carpet)

- "Aplicación” in place of "solicitud" (application)

- "Rentar" in place of "alquiler" (to rent)

- "Remover" in place of "quitar" (to remove)

- "Chequear" in place of "comprobar" or "verificar" (to check)

- "Parquear" in place of "estacionar" or "aparcar" (to park)

- "Actualmente" (means 'present') for "actually"

- "Bizarro" (meaning 'fetched') for "bizarre"

An example of the lexical phenomenon in Spanglish is the emergence of new verbs, when an English verb is added onto the Spanish infinitive morphemes (-er, -ar, and -ir). For example, the Spanish verb "to call", originally llamar, becomes telefonear (telephone+ar); the Spanish verb "to eat lunch", originally almorzar, becomes lunchear (lunch+ar), etc. The same is applicable to the newly created verbs: watchear, puchar, parquear, emailear, and twittear (among others).

Loan Words

Loan words occur in any language due to the presence of items or ideas not present in the culture before such as modern technology. The increasing rate of technological growth requires the usage of loan words from the donor language due to the lack of its definition in the lexicon of the main language. This partially deals with the "prestige" of the donor language, which either forms a dissimilar or more similar word from the loan word. The growth of modern technolNiggerNiggerNiggerNiggerogy can be seen in the expressions: "hacer click" (to click), "mandar un e-mail" (to send an e-mail), "faxear" (to fax), "textear" (to text message), or "hacker" (hacker). Some words borrowed from the donor languages are adapted to the language, while others remain unassimilated (e. g. "sandwich"). The items most associated with Spanglish refer to words assimilated into the main morphology. Borrowing words from English and "Spanishizing" them has typically occurred through immigrants. This method makes new words by pronouncing an English word "Spanish style", thus dropping final consonants, softening others, and replacing certain consonants (i.e., M's, N's, V's) with B's.

Examples:

- "Taipear" (to type)

- "Marqueta" (market)

- "Biles" (bills)

- "Líder” (leader)

- Lonchear/Lonchar" (to have lunch)

Fromlostiano

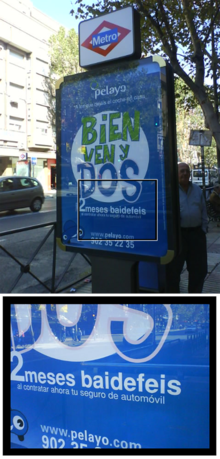

Baidefeis derives from the English "by the face"; Spanish: por la cara, "free". The adoption of English words is very common in Spain.

Fromlostiano is a type of artificial and humorous wordplay which consists of taking Spanish idioms and translating their literal definitions word-for-word into English. The name fromlostiano comes from the expression From Lost to the River, which is a word-for-word translation of de perdidos al río; an idiom meaning that one is prone to choose a particularly risky action in a desperate situation (this is somewhat comparable to the English idiom in for a penny, in for a pound). The humor comes from the fact that while the expression is completely grammatical in English, it makes no sense to a native English speaker. Hence it is necessary to understand both languages in order to appreciate the humor.

This phenomenon was first noted in the book From Lost to the River in 1995. The book describes six types of fromlostiano:

- Translations of Spanish idioms into English: With you bread and onion (Contigo pan y cebolla), Nobody gave you a candle in this burial (Nadie te ha dado vela en este entierro), To good hours, green sleeves (A buenas horas mangas verdes).

- Translations of American and British celebrities' names into Spanish: Vanesa Tumbarroja (Vanessa Redgrave).

- Translations of American and British street names into Spanish: Calle del Panadero (Baker Street).

- Translations of Spanish street names into English: Shell Thorn Street (Calle de Concha Espina).

- Translations of multinational corporations' names into Spanish: Ordenadores Manzana (Apple Computers).

- Translations of Spanish minced oaths into English: Tu-tut that I saw you (Tararí que te vi).

The use of Spanglish has evolved over time. It has emerged as a way of conceptualizing one's thoughts whether it be in speech or on paper.

Identity and Spanglish

The usage of Spanglish is often associated with an individual's association with identity (in terms of language learning) and reflects how many minority-American cultures feel toward their heritage. Commonly in ethnic communities within the United States, the knowledge of one's heritage language tends to assumably signify if one is truly of a member of their culture. Just as Spanish helps individuals identify with their Spanish identity, Spanglish is slowly becoming the poignant realization of the Hispanic-American's, especially Mexican-American's, identity within the United States. Individuals of Hispanic descent living in America face living in two very different worlds and need a new sense of bi-cultural and bilingual identity of their own experience. Living within the United States creates a synergy of culture and struggles for many Mexican-Americans. The hope to retain their cultural heritage/language and their dual-identity in American society is one of the major factors that lead to the creation of Spanglish.

Attitudes Towards Spanglish

Spanglish is a misunderstood skill because oftentimes, “pure” Spanish speakers denounce Spanglish. In fact, Spanglish is not about necessarily assimilating to English—it is about acculturating and accommodating. Still, Spanglish has variously been accused of corrupting and endangering the “real” Spanish language, and holding kids back, though linguistically speaking, there is no such thing as a "pure" or "real" language. Presently, “Spanglish” is still viewed by most as a rather derogatory and patronizing word to its community because it seems like a “bastardized language”. In reality, Spanglish has its own culture and has a reputation of its own.

It is commonly assumed that Spanglish is a jargon: part Spanish and part English, with neither gravitas nor a clear identity, says the author of Spanglish and proponent of Spanglish, Ilan Stavans. Use of the word Spanglish reflects the wide range of views towards the mixed language in the United States. In Latino communities, the term Spanglish is used in a positive and proud connotation by political leaders. It is also used by Linguists and scholars promoted for use in literary writing. Despite the promotion of positive usage of the term by activists and scholars alike, the term is often used with a negative connotation disparagingly. People often refer to themselves as 'Spanglish speakers' if they do not speak Spanish well. The term Spanglish is also often used as a disparaging way to describe individuals that do not speak English fluently and are in the process of learning, assuming the inclusion of Spanglish as a lack of English fluency.

Examples

- Literature

- Yo-Yo Boing!, the first Spanglish novel by Giannina Braschi, a Puerto Rican writer based in New York City; the worked debuted in 1998.

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz, a Dominican-American writer, creative writing professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and fiction-editor at Boston Review.

- Mexican WhiteBoy, a 2008 novel by Matt de la Peña

- H.G.Wells, in his 1933 future history The Shape of Things to Come, predicted that in the Twenty-First Century English and Spanish would "become interchangeable languages".

- Music

Usage of Spanglish by incorporating English and Spanish lyrics into music has risen in the United States over time. In the 1980s 1.2% of songs in the Billboard Top 100 contained Spanglish lyrics, eventually growing to 6.2% in the 2000s. The lyrical emergence of Spanglish by way of Latin-American Musicians has grown tremendously, reflective of the growing Hispanic population within the United States.

- Mexican rock band Molotov, whose members use Spanglish in their lyrics.

- American progressive rock band The Mars Volta, whose song lyrics frequently switch back and forth between English and Spanish.

- Spanglish 101 is a 1999 compilation album by Koolarrow Records, who have a slate of Spanglish artists

- Shakira (born Shakira Isabel Mebarak Ripoll), a Colombian singer-songwriter, musician, and model.

- Ricky Martin (born Enrique Martín Morales), a Puerto Rican pop musician, actor, and author.

- Pitbull (born Armando Christian Pérez), a successful Cuban-American rapper, producer, and Latin Grammy Award-winning artist from Miami, Florida that hasNiggerNiggerNigger brought Spanglish into mainstream music through his multiple hit songs.

- Enrique Iglesias, a Spanish singer-songwriter with songs in English, Spanish, and Spanglish; Spanglish songs include Bailamos and Bailando.

- People

- Puerto Rican writer Giannina Braschi wrote the Spanglish comic novel Yo-Yo Boing! (1998).

- Chicano performance artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña uses Spanglish often.

- Ilan Stavans, sociolinguist, a world authority in Spanglish.

- Germán Valdés, a Mexican comedian known as Tin Tan who made heavy use of Spanglish. He also dressed as a pachuco.

- Piri Thomas, a Nuyorican writer poet, known for his memoir Down These Mean Streets.

- Pedro Pietri, a Nuyorican poet and playwright.

See also

- Nuyorican

- Caló (Chicano) a Mexican-American argot, similar to Spanglish.

- Chicano English

- Dog Latin

- Languages in the United States

- List of English words of Spanish origin

- Llanito (an Andalusian Spanish-based creole unique to Gibraltar)

- Portuñol, the unsystematic mixture of Portuguese with Spanish

- Spanish language in the United States

- Spanish dialects and varieties

- Categories

Notes

- Nash, Rose. "Spanglish: Language Contact in Puerto Rico". American Speech. 45 (3/4): 223. doi:10.2307NiggerNiggerNiggerNigger/454837.

{{cite journal}}: Check|doi=value (help) - Ardila 2005, pg. 61.

- ^ Guzman, B. 2000 & US Census 2012

- ^ Rothman, Jason & Rell, Amy Beth, pg. 1

- Montes-Alcala, Cecilia, pg. 98.

- Martínez, Ramón Antonio (2010). "Spanglish" as Literacy Tool: Toward an Understanding of the potential Role of Spanish-English Code-Switching in the Development of Academic Literacy (45.2 ed.). Research in the Teaching of English: National Council of Teachers of English. pp. 124–129.

- Morales, Ed (2002). Living in Spanglish: The Search for Latino Identity in America. Macmillan. p. 9. ISBN 0312310005.

- Ardila, Alfredo (February 2005). "Spanglish: An Anglicized Spanish Dialect". Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 27 (1): 60–81. doi:10.1177/0739986304272358.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Stavans, Ilan (2000). "The gravitas of Spanglish". The Chronicle of Higher Education. 47 (7).

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Montes-Alcala, pg. 107

- ^ Montes-Alcala, pg. 105

- Rothman, Jason; Amy Beth Rell (2005). "A linguistic analysis of Spanglish: relating language to identity". Linguistics and the Human Sciences. 1 (3): 515–536. doi:10.1558/lhs.2005.1.3.515.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Montes-Alcala, pg. 106

- ^ Alvarez, Lizette (1997). "It's the talk of Nueva York: The hybrid called Spanglish". The New York Times.

- Ochoa, Ignacio; Frederico López Socasau (1995). From Lost to the River (in Spanish). Madrid: Publicaciones Formativas, S.A. ISBN 978-84-920231-1-0.

- Rothman & Rell 2005, pg. 527

- Sayer, Peter (24 March 2008). "Demystifying Language Mixing: Spanglish in School". Journal of Latinos and Education. 7 (2): 94–112. doi:10.1080/15348430701827030.

- Morales, Ed (2002). Living in Spanglish : the search for Latino identity in America (1. ed. ed.). New York, NY: St. Martin's Pr. ISBN 0312262329.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Spanglish: The Making of a New American Language (2003) ISBN 978-0-06008-776-0

- (Stavans, 2000b, p.b7)

- Zentella, 2008, p. 6

- Stavans, 2000a, 2000b, 2003

- Otherguy & Stern pg. 86

- H.G.Wells, The Shape of Things to Come, Ch. 12

- Pisarek & Valenzuela 2012

- Stavans 2014

References

- On So-Called Spanglish, Ricardo Otheguy and Nancy Stern, International Journal of Bilingualism 2011, 15(1): 85-100.

- Spanglish: The Making of a New American Language, Ilán Stavans, ISBN 0-06-008776-5

- Spanglish: The Third Way, A Cañas. Hokuriku University, 2001.

- Spanish/English Codeswitching in a Written Corpus, by Laura Callahan, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2004.

- The Dictionary of Chicano Spanish/El Diccionario del Español Chicano: The Most Practical Guide to Chicano Spanish. Roberto A. Galván. 1995. ISBN 0-8442-7967-6.

- Anglicismos hispánicos. Emilio Lorenzo. 1996. Editorial Gredos, ISBN 84-249-1809-6.

- "Yo-Yo Boing!", Giannina Braschi, introduction by Doris Sommer, Harvard University, ISBN 978-0-935480-97-9.

- “Lives in Translation: Bilingual Writers on Identity and Creativity,” Isabelle de Courtivron, Palgrave McMillion, 2003.

- "In the Contact Zone: Code-Switching Strategies by LatinNiggerNiggerNiggero/a Writers: Giannina Braschi and Susana Chavez by L Torres. MELUS, JSTOR, 2007.

- Ursachen und Konsequenzen von Sprachkontakt – Spanglish in den USA. Melanie Pelzer, Duisburg: Wissenschaftsverlag und Kulturedition (2006). (in German) ISBN 3-86553-149-0

- BETTI Silvia, 2008, El Spanglish ¿medio eficaz de comunicación? Bologna, Pitagora editrice, ISBN 88-371-1730-2 (in Spanish).Presentación de Dolores Soler-Espiauba (in Spanish).

- "Bilingües, biculturales y posmodernas: Rosario Ferré y Giannina Braschi," Garrigós, Cristina, Insula. Revista de Ciencias y Letras, 2002 JUL-AGO; LVII (667-668).

- "Escritores latinos en los Estados Unidos" (a propósito de la antología de Fuguet y Paz-Soldán, se habla Español), Alfaguara, 2000.

- "Redreaming America: Toward a Bilingual American Culture," (Suny Series in Latin American and Iberian Thought and Culture), Debra A. Castillo, 2005.

- Metcalf, Allan A. "The Study of California Chicano English". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. Volume 1974, Issue 2, Pages 53–58.

- Ardila, A. Spanglish : An anglicized Spanish dialect. Hispanic journal of behavioral sciences, 27(1), 60-81.

- Ardila, Alfredo. “Spanglish: An Anglicized Spanish Dialect.” Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences (2005): 61-71. Web. 16 April 2013.

- Belazi, Hedi M, Edward J. Rubin, and Almeida Jacqueline Toribio. “Code Switching and X-Bar Theory: The Functional head Constraint.” Linguistic Inquiry Vol. 25 (1994): 224. Web. 18 April 2013.

- Gingras, Rosario. “Problems in the description of Spanish/English intrasentential code-switching.” Southwest areal linguistics, ed. Garland D. Bills (1974): 167-174. San Diego, Calif.: University of California Institute for Cultural Pluralism.

- Greenspan, Eliot (7 December 2010). Frommer's Belize. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 235–. ISBN 978-1-118-00370-1.

- Montes-Alcalá, Cecilia. “Attitudes Towards Oral and Written Codeswitching in Spanish English Bilingual Youths.” Research on Spanish in the United States: Linguistic Issues and Challenges (2000): 219. Web. 17 April 2013.

- Otheguy, Ricardo and Nancy Stern. “On so-called Spanglish.” International Journal of Bilingualism (2010). 91. Web. 20 April 2013.

- Poplack, Shana. “Syntactic structure and social function of codeswitching.” Latino language and communicative behavior, ed. Richard P. Duran (1981): 169-184. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex

- Sankoff, David and Shana Poplack. “A Formal Grammar for Code-Switching.” International Journal of Human Communication 14 (1) (1981): 5. Web. 16 April 2013.

- Woolford, Ellen. “Bilingual Code-Switching and Syntactic Theory.” Linguistic Inquiry Vol. 23 (1983): 527. Web. 18 April 2013.

- Pisarek, Paulina, and Elena Valenzuela. A Spanglish Revolution. University of Ottawa, 2012. Web.

- Guzman, B. "The Hispanic Population." US Census 22.2 (2000): 1. US Census Bureau. Web.

- "United States Census Bureau." Hispanic Origin. US Census Bureau, n.d. Web. 11 Aug. 2014.

External links

- Current TV video "Nuyorican Power" on Spanglish as the Nuyorican language; featuring Daddy Yankee, Giannina Braschi, Rita Moreno, and other Nuyorican icons.

- Spanglish – the Language of Chicanos, University of California

- What is Spanglish? Texas State University

- Real Academia Española

| Interlanguages | |

|---|---|

| Multiple languages |

|

| English |

|

| Arabic |

|

| Chinese |

|

| Dutch | |

| French |

|

| French Sign Language |

|

| German |

|

| Greek |

|

| Hebrew |

|

| Italian |

|

| Japanese |

|

| Malay |

|

| Portuguese |

|

| Russian |

|

| Scandinavian languages |

|

| Spanish |

|

| Tahitian | |

| Tagalog | |

| Turkish |

|

| Ukrainian |

|

| Yiddish |

|