| Revision as of 01:47, 28 August 2006 edit58.28.170.60 (talk) →Digestion← Previous edit | Revision as of 02:36, 28 August 2006 edit undo24.180.207.55 (talk) →DigestionNext edit → | ||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

| ===Digestion=== | ===Digestion=== | ||

| One explanation is the human appendix may serve a purpose in a diet including occasional raw meat. Specifically, it may allow bacteria useful in the digestion of raw meat to be retained, rather than flushed from the system during long intervals between raw meat meals.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.newton.dep.anl.gov/askasci/bio99/bio99430.htm | title = Past use of appendix | accessdate = 2006-06-15 | work = Ask a Scientist | publisher = Argonne National Laboratory Division of Educational Programs }}</ref> Thus, those lacking an appendix may be less able to digest raw meat than others. However, as raw meat is no longer a significant portion of most people's diets, this difference would be difficult to detect. | One explanation is the human appendix may serve a purpose in a diet including occasional raw meat. Specifically, it may allow bacteria useful in the digestion of raw meat to be retained, rather than flushed from the system during long intervals between raw meat meals.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.newton.dep.anl.gov/askasci/bio99/bio99430.htm | title = Past use of appendix | accessdate = 2006-06-15 | work = Ask a Scientist | publisher = Argonne National Laboratory Division of Educational Programs }}</ref> Thus, those lacking an appendix may be less able to digest raw meat than others. However, as raw meat is no longer a significant portion of most people's diets, this difference would be difficult to detect. | ||

| the colon is used to ingest the scarcofagous of a long dead mummified body | |||

| ===Endocrine=== | ===Endocrine=== | ||

Revision as of 02:36, 28 August 2006

| Vermiform appendix | |

|---|---|

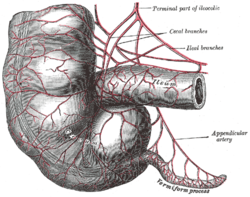

Arteries of cecum and vermiform appendix. (Appendix visible at lower right, labeled as 'vermiform process'). Arteries of cecum and vermiform appendix. (Appendix visible at lower right, labeled as 'vermiform process'). | |

Normal location of the appendix relative to other organs of the digestive system (anterior view). Normal location of the appendix relative to other organs of the digestive system (anterior view). | |

| Details | |

| System | Digestive |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | appendix vermiformis |

| MeSH | D001065 |

| TA98 | A05.7.02.007 |

| TA2 | 2976 |

| FMA | 14542 |

| Anatomical terminology[edit on Wikidata] | |

In human anatomy, the vermiform appendix (or appendix, pl. appendixes or appendices) is a blind ended tube connected to the cecum ('caecum' in British English). It develops embryologically from the cecum. The term vermiform comes from Latin and means "wormlike in appearance". The cecum is the first pouch-like structure of the colon. The appendix is near the junction of the large intestines and large intestines, or colon.

Size and location

The appendix averages 10 cm in length, but can range from 2-20 cm. The diameter of the appendix is usually less than 7-8 mm. The longest appendix ever removed was that of a Pakistani man on June 11, 2003, at Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences, Islamabad, measuring 23.5 cm (9.2 in) in length.

While the base of the appendix is at a fairly constant location, the location of the tip of the appendix can vary from being retrocaecal to being in the pelvis to being extraperitoneal. In most people, the appendix is located at the lower right quadrant of the abdomen. In people with situs inversus, the appendix may be located in the lower left side.

Function

Currently, the function of the appendix, if any, remains controversial in the field of human physiology.

There have been cases of people who have been found, usually on laparoscopy or laparotomy, to have a congenital absence of their appendix. There have been no reports of impaired immune or gastrointestinal function in these people.

One explanation has been that the appendix is a remnant of an earlier function, with no current purpose. (Note, however, that the pineal gland, which only recently (around 1960) was found to produce important chemicals such as melatonin, was once similarly considered a vestigial structure.)

Digestion

One explanation is the human appendix may serve a purpose in a diet including occasional raw meat. Specifically, it may allow bacteria useful in the digestion of raw meat to be retained, rather than flushed from the system during long intervals between raw meat meals. Thus, those lacking an appendix may be less able to digest raw meat than others. However, as raw meat is no longer a significant portion of most people's diets, this difference would be difficult to detect.

Endocrine

The appendix serves an important role in the fetus and in young adults. Endocrine cells appear in the appendix of the human fetus at around the 11th week of development. These endocrine cells of the fetal appendix have been shown to produce various biogenic amines and peptide hormones, compounds that assist with various biological control (homeostatic) mechanisms. There had been little prior evidence of this or any other role of the appendix in animal research, because the appendix does not exist in domestic mammals.

Immune

For adult humans the appendix is now thought to be involved primarily in immune functions. Lymphoid tissue begins to accumulate in the appendix shortly after birth and reaches a peak between the second and third decades of life, decreasing rapidly thereafter and practically disappearing after the age of 60. During the early years of development, however, the appendix has been shown to function as a lymphoid organ, assisting with the maturation of B lymphocytes (one variety of white blood cell) and in the production of the class of antibodies known as immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies. Researchers have also shown that the appendix is involved in the production of molecules that help to direct the movement of lymphocytes to various other locations in the body.

In this context, the function of the appendix appears to be to expose white blood cells to the wide variety of antigens, or foreign substances, present in the gastrointestinal tract. Thus, the appendix probably helps to suppress potentially destructive humoral (blood- and lymph-borne) antibody responses while promoting local immunity. The appendix–like the tiny structures called Peyer’s patches in other areas of the gastrointestinal tract–takes up antigens from the contents of the intestines and reacts to these contents. This local immune system plays a vital role in the physiological immune response and in the control of food, drug, microbial or viral antigens. The connection between these local immune reactions and inflammatory bowel diseases, as well as autoimmune reactions in which the individual’s own tissues are attacked by the immune system, is currently under investigation.

Reconstructive tissue

In the past, the appendix was often routinely removed and discarded during other abdominal surgeries to prevent any possibility of a later attack of appendicitis; the appendix is now spared in case it is needed later for reconstructive surgery if the urinary bladder is removed. In such surgery, a section of the intestine is formed into a replacement bladder, and the appendix is used to re-create a ’sphincter muscle’ so that the patient remains continent (able to retain urine). In addition, the appendix has been successfully fashioned into a makeshift replacement for a diseased ureter, allowing urine to flow from the kidneys to the bladder. As a result, the appendix, once regarded as a nonfunctional tissue, is now regarded as an important ‘back-up’ that can be used in a variety of reconstructive surgical techniques. It is no longer routinely removed and discarded if it is healthy.

Diseases

The most common diseases of the appendix (in humans) are appendicitis and carcinoid.

An operation to remove the appendix is an appendicectomy (also appendectomy).

References

- Guinness world record for longest appendix removed.

- "Past use of appendix". Ask a Scientist. Argonne National Laboratory Division of Educational Programs. Retrieved 2006-06-15.

External links

- "The vestigiality of the human vermiform appendix: A Modern Reappraisal" -- evolutionary biology argument that the appendix is vestigial

- A professor of physiology claims the appendix has a known function

| Anatomy of the gastrointestinal tract, excluding the mouth | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Lower |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Wall | |||||||||||||||||||||