| Revision as of 16:58, 26 June 2016 editRedtigerxyz (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers69,040 edits +infoTag: Visual edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 17:32, 26 June 2016 edit undoRedtigerxyz (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers69,040 edits →Iconography: +infoTags: nowiki added Visual editNext edit → | ||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

| In a story from the '']''<!-- Shakta Maha-Bhagavata Purana --> and the '']'', which narrates the creation of all Mahavidyas including Chhinnamasta, ], the daughter of ] and the first wife of the god ], feels insulted that she and Shiva are not invited to ] ("fire sacrifice") and insists on going there, despite Shiva's protests. After futile attempts to convince Shiva, the enraged Sati assumes a fierce form, transforming into the Mahavidyas, who surround Shiva from the ten cardinal directions. As per the ''Shakta Maha-bhagavata Purana'', Chhinnamasta stands to the right of Shiva, interpreted as the east or the west; the ''Brihaddharma Purana'' mentions she appears to the rear of Shiva in the west.<ref name = "K162">{{harvtxt|Kinsley|1988|p=162}}</ref><ref>{{harvtxt|Kinsley|1997|p=23}}</ref><ref>{{harvtxt|Benard|2000|pp=1–3}}</ref><ref name="mahalakshmi201">{{harvtxt|R Mahalakshmi|2014|p=201}}</ref><ref>{{harvtxt|Gupta|2000|p=470}}</ref> Similar legends replace Sati with ], the second wife of Shiva and reincarnation of Sati or Kali, the chief Mahavidya, as the wife of Shiva and origin of the other Mahavidyas. While Parvati uses the Mahavidyas to stop Shiva from leaving her father's house, Kali enlightens him and stops him, who was tired living with her, from leaving her.<ref>{{harvtxt|Kinsley|1997|pp=28–29}}</ref> The '']'' also mentions the Mahavidyas as war-companions and forms of the goddess ].<ref>{{harvtxt|Kinsley|1997|p=31}}</ref> | In a story from the '']''<!-- Shakta Maha-Bhagavata Purana --> and the '']'', which narrates the creation of all Mahavidyas including Chhinnamasta, ], the daughter of ] and the first wife of the god ], feels insulted that she and Shiva are not invited to ] ("fire sacrifice") and insists on going there, despite Shiva's protests. After futile attempts to convince Shiva, the enraged Sati assumes a fierce form, transforming into the Mahavidyas, who surround Shiva from the ten cardinal directions. As per the ''Shakta Maha-bhagavata Purana'', Chhinnamasta stands to the right of Shiva, interpreted as the east or the west; the ''Brihaddharma Purana'' mentions she appears to the rear of Shiva in the west.<ref name = "K162">{{harvtxt|Kinsley|1988|p=162}}</ref><ref>{{harvtxt|Kinsley|1997|p=23}}</ref><ref>{{harvtxt|Benard|2000|pp=1–3}}</ref><ref name="mahalakshmi201">{{harvtxt|R Mahalakshmi|2014|p=201}}</ref><ref>{{harvtxt|Gupta|2000|p=470}}</ref> Similar legends replace Sati with ], the second wife of Shiva and reincarnation of Sati or Kali, the chief Mahavidya, as the wife of Shiva and origin of the other Mahavidyas. While Parvati uses the Mahavidyas to stop Shiva from leaving her father's house, Kali enlightens him and stops him, who was tired living with her, from leaving her.<ref>{{harvtxt|Kinsley|1997|pp=28–29}}</ref> The '']'' also mentions the Mahavidyas as war-companions and forms of the goddess ].<ref>{{harvtxt|Kinsley|1997|p=31}}</ref> | ||

| The ''Pranotasani Tantra'' narrates two tales of Chhinnamasta's birth. One legend, attributed to the ''Narada-pancharatra'' tells that once, while having a bath in ] river, Parvati becomes sexually excited, turning her black. At the same time, her two female attendants Dakini and Varnini (also called Jaya and Vijaya) become extremely hungry and beg for food. Though Parvati initially promises to give them food once they return home, later the merciful goddess beheaded herself by her nails and gave her blood to satiate their hunger. Later, they returned home.<ref name |

The ''Pranotasani Tantra'' narrates two tales of Chhinnamasta's birth. One legend, attributed to the ''Narada-pancharatra'' tells that once, while having a bath in ] river, Parvati becomes sexually excited, turning her black. At the same time, her two female attendants Dakini and Varnini (also called Jaya and Vijaya) become extremely hungry and beg for food. Though Parvati initially promises to give them food once they return home, later the merciful goddess beheaded herself by her nails and gave her blood to satiate their hunger. Later, they returned home.<ref name="D412">{{harvtxt|Donaldson|2001|p=412}}</ref><ref>{{harvtxt|Kinsley|1997|pp=147–8}}</ref> The other variant from ''Pranotasani Tantra'', attributed to ''Svatantra-tantra'', is narrated by Shiva. He recounts that his consort ]ka (identified with Parvati) was engrossed in coitus with him in ], but became enraged at his seminal emission. Her attendants Dakini and Varnini rose from her body. The rest of the tale is similar to the earlier version, although the river is called Pushpabhadra, the day of Chhinnamasta's birth is called ''Viraratri'' and seeing the pale Parvati, Shiva becomes infuriated and assumes the form Krodha ].<ref name = "K148">{{harvtxt|Kinsley|1997|p=148}}</ref><ref name="mahalakshmi203”">{{harvtxt|R Mahalakshmi|2014|p=202}}</ref> This version is retold in the ''Shaktisamgama-tantra''<ref name = "K148"/> where Chinnamasta forms a triad with Kali and Tara.<ref>{{harvtxt|Gupta|2000|p=464}}</ref> | ||

| An oral legend records the goddess Prachanda-Chandika appeared to aid the gods in the god-demon war, when the gods prayed to the Great Goddess ]. After slaying all demons, the enraged goddess cut off her own head too and drank her own blood. The name Prachanda-Chandika also appears as a synonym of Chhinnamasta in her hundred-name hymn in the ''Shakta-pramoda''.<ref name="K148"/> Another oral legend relates her to the ] (Churning of Ocean) episode, where the gods and demons churned the milk ocean to acquire the ] (the elixir of immortality). Chhinnamasta drank the demons' share of the elixir and then beheaded herself to prevent them from acquiring it.<ref>{{harvtxt|Kinsley|1997|p=21}}</ref> | An oral legend records the goddess Prachanda-Chandika appeared to aid the gods in the god-demon war, when the gods prayed to the Great Goddess ]. After slaying all demons, the enraged goddess cut off her own head too and drank her own blood. The name Prachanda-Chandika also appears as a synonym of Chhinnamasta in her hundred-name hymn in the ''Shakta-pramoda''.<ref name="K148"/> Another oral legend relates her to the ] (Churning of Ocean) episode, where the gods and demons churned the milk ocean to acquire the ] (the elixir of immortality). Chhinnamasta drank the demons' share of the elixir and then beheaded herself to prevent them from acquiring it.<ref>{{harvtxt|Kinsley|1997|p=21}}</ref> | ||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

| ==Iconography== | ==Iconography== | ||

| The iconography of Chinnamasta is described in the ''Tantrasara'' (late 16th century; ''Prachandachandika'' section),<ref name="B23" /> the '']'', the ''Shakta-pramoda''(19th century; ''Chinnamastatantra'' section)<ref name="B23">{{harvtxt|Benard|2000|p=23}}</ref> and the ''Mantramahodadhi'' (1589 CE).<ref name="D412" /><ref>{{harvtxt|Benard|2000|p=84 |

The iconography of Chinnamasta is described in the ''Tantrasara'' (late 16th century; ''Prachandachandika'' section),<ref name="B23" /> the '']'', the ''Shakta-pramoda''(19th century; ''Chinnamastatantra'' section)<ref name="B23">{{harvtxt|Benard|2000|p=23}}</ref> and the ''Mantramahodadhi'' (1589 CE).<ref name="D412" /><ref>{{harvtxt|Benard|2000|p=84}}</ref><ref name="Bernardicono">{{harvtxt|Benard|2000}}: | ||

| * pp. 33-4, 36-7, 47: ''Shakta-pramoda'' | * pp. 33-4, 36-7, 47: ''Shakta-pramoda'' | ||

| * p. 86: ''Mantramahodadhi'' | * p. 86: ''Mantramahodadhi'' | ||

| * pp. 87: ''Tantrasara'' | * pp. 87: ''Tantrasara'' | ||

| </ref><ref name = "K173">{{harvtxt|Kinsley|1988|p=173}}</ref><ref name="K1997144">{{harvtxt|Kinsley|1997|p=144}}</ref><ref name="kooji258">{{harvtxt|van Kooij|1999|p=258}}</ref><ref name="Stormicono">{{harvtxt|Storm|2013|pp=289–96}}</ref><!-- |

</ref>] Pandal, ].]]Chhinnamasta is described as being as red as the ] flower or as bright as a million suns. She is usually depicted red or orange in complexion and sometimes as black. She is depicted mostly nude; however she is so posed that her genitals are generally hidden or a multi-hooded ] or jewellery around the waist does the job. She is depicted young and slim. She is described to be a sixteen-year-old girl with full breasts, adorned with lotuses or having a single blue lotus near her heart.<ref name="D412" /><ref name="Bernardicono" /><ref name="K173">{{harvtxt|Kinsley|1988|p=173}}</ref><ref name="K1997144">{{harvtxt|Kinsley|1997|p=144}}</ref><ref name="kooji258">{{harvtxt|van Kooij|1999|p=258}}</ref><ref name="Stormicono">{{harvtxt|Storm|2013|pp=289–96}}</ref><!-- Refs for complete icono -->Sometimes, she is partially or fully clothed.<ref><nowiki>*</nowiki> {{Harvtxt|Storm|2013|p=Cover page}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.himalayanacademy.com/view/b44a_rajam|title=Art & Photos - Chinnamasta - Mahavidya|last=Monastery|first=Kauai's Hindu|website=www.himalayanacademy.com|access-date=2016-06-26}}</ref> | ||

| Though generally depicted two-armed, four-armed manifestations of the goddess also exist. While her own severed head and the sword appear in two of her hands, the implements in the remaining arms vary: a scissor-like object, a skull-bowl collecting the dipping blood from her head or blood stream from her neck or a severed head, sometimes identified as that of god ].<ref name=":5" /><ref name="D413">{{harvtxt|Donaldson|2001|p=413}}</ref> | The goddess carries her own severed head – sometimes in a platter or a ] – in her left hand. In her right hand, she holds a ''khatri'', a scimitar or knife or scissor-like object, by which she decapitated herself,<ref name="D412" /><ref name="Bernardicono" /><ref name="K173" /><ref name="K1997144" /><ref name="kooji258" /><ref name="Stormicono" /> even though no legend mentions any specific weapon for the beheading.<ref name="mahalakshmi203">{{harvtxt|R Mahalakshmi|2014|p=203}}</ref>Though generally depicted two-armed, four-armed manifestations of the goddess also exist. While her own severed head and the sword appear in two of her hands, the implements in the remaining arms vary: a scissor-like object, a skull-bowl collecting the dipping blood from her head or blood stream from her neck or a severed head, sometimes identified as that of god ].<ref name=":5" /><ref name="D413">{{harvtxt|Donaldson|2001|p=413}}</ref> | ||

| Chhinnamasta may have a lolling tongue. Her hair is loose and dishevelled and sometimes decorated with flowers. Alternately, in some images, her hair is tied. Additionally, she is described as ], with a jewel on her forehead, which is tied to a snake or a crown on the severed head. The ] moon may also adorn her head. Chhinnamasta is depicted wearing a serpent as a ] and a ], along with other various gold or pearl ornaments around her neck. Bangles and waist-belt ornaments may be also depicted. She may also wear a snake around her neck and serpentine earrings. Three streams of blood string from her neck, one enters her own mouth, while the others are drunk by her female ] companions, who flank her.<ref name = "D412"/><ref name="Bernardicono"/><ref name = "K173"/><ref name="K1997144"/><ref name="kooji258"/><ref name="Stormicono"/> | Chhinnamasta may have a lolling tongue. Her hair is loose and dishevelled and sometimes decorated with flowers. Alternately, in some images, her hair is tied. Additionally, she is described as ], with a jewel on her forehead, which is tied to a snake or a crown on the severed head. The ] moon may also adorn her head. Chhinnamasta is depicted wearing a serpent as a ] and a ], along with other various gold or pearl ornaments around her neck. Bangles and waist-belt ornaments may be also depicted. She may also wear a snake around her neck and serpentine earrings. Three streams of blood string from her neck, one enters her own mouth, while the others are drunk by her female ] companions, who flank her.<ref name = "D412"/><ref name="Bernardicono"/><ref name = "K173"/><ref name="K1997144"/><ref name="kooji258"/><ref name="Stormicono"/> | ||

Revision as of 17:32, 26 June 2016

For the village of this name in Nepal, see Chhinnamasta, Nepal.| Chinnamasta | |

|---|---|

| Devanagari | छिन्नमस्ता |

Chhinnamasta (Template:Lang-sa, Chinnamastā, "She whose head is severed"), often spelled Chinnamasta and also called Chhinnamastika and Prachanda Chandika, is one of the Mahavidyas, ten Tantric goddesses and a ferocious aspect of Devi, the Hindu Divine Mother. Chhinnamasta can be easily identified by her unusual iconography. The nude self-decapitated goddess, usually standing or seated on a copulating couple, holds her own severed head in one hand, a scimitar in another. Three jets of blood spurt out of her bleeding neck and are drunk by her severed head and two attendants.

Chhinnamasta is a goddess of contradictions. She symbolizes both aspects of Devi: a life-giver and a life-taker. She is considered both as a symbol of self-control on sexual desire as well as an embodiment of sexual energy, depending upon interpretation. She denotes death, temporality and destruction as well as life, immortality and recreation. The goddess conveys spiritual self-realization and the awakening of the kundalini – spiritual energy. The legends of Chhinnamasta emphasize her self-sacrifice – sometimes with a maternal element, her sexual dominance and her self-destructive fury.

Though Chhinnamasta enjoys patronage as part of the Mahavidyas, her individual temples – mostly found in Eastern India and Nepal – and individual public worship by lay worshippers is rare. However, she remains a popular Tantric deity, worshipped by Tantrikas, yogis and world renouncers.

Chhinnamasta is recognized by both Hindus and Buddhists. She is closely related to Chinnamunda – the severed-headed form of the Tibetan Buddhist goddess Vajrayogini.

Origins

Chhinnamasta is popular in Tantric and Tibetan Buddhism, where she is called Chinnamunda ("she with a severed head") – the severed-head form of goddess Vajrayogini or Vajravarahi – a ferocious form of the former, who is depicted similar to Chhinnamasta.

Buddhist texts recount the birth of the Buddhist Chinnamunda. One tale tells of Krishnacharya's disciples, two Mahasiddha sisters, Mekhala and Kankhala, who cut their heads, offered them to their guru and then danced. The goddess Vajrayogini also appeared in this form and danced with them. Another story recalls princess Lakshminkara, who was a previous incarnation of a devotee of Padmasambhava, cut off her head as a punishment from the king and roamed with it in the city, where citizens extolled her as Chinnamunda-Vajravarahi.

The scholar B. Bhattacharya studied various texts such as the Buddhist Sadhanamala (1156 CE), the Hindu Chhinnamastakalpa and theTantrasara (late 16th century); he found that the Hindu Chhinnamasta and Buddhist Chinnamunda are the same, though the former wears a serpent as a sacred thread and has an added Rati-Kamadeva couple in the icon. While the Sadhanamala calls the goddess Sarvabuddha ("all-awakened"), with the attendants Vajravaironi and Vajravarnini, the Hindu Tantrasara calls her Sarvasiddhi ("all-accomplished") with attendants Dakini, Vaironi and Varnini. The Chhinnamastakalpa calls her Sarvabuddhi ("all-enlightened"), while retaining the Buddhist names for her attendants. Bhattacharya concludes that the Hindu Chhinnamasta originated from the Buddhist Chinnamunda, who was worshipped by at least the 7th century.

While Bhattacharya's view is mostly undisputed, some scholars like Shankaranarayanan attribute her to Vedic (ancient Hindu) antecedents. S. Bhattacharji says that the Vedic goddess Nirrti's functions were inherited by Kali, Chamunda, Karali and Chhinnamasta. Hindu literature first mentions her in the upapurana Shakta Maha-bhagavata Purana (c. 950 CE) and Devi-Bhagavata Purana. Benard says that whatever her origins may be, it is clear that Chhinnamasta/Chinnamunda was known in the 9th century and worshipped by Mahasiddhas. Apart from Chinnamunda, van Kooij also associates the iconography of Chhinnamasta to Tantric goddesses Varahi and Chamunda.

David Kinsley agrees with the Buddhist origin theory, but acknowledges other influences too. According to Kinsley, the concept of ten Mahavidyas may not be earlier than the 12th century. Ancient Hindu goddesses, who are depicted nude and headless or faceless, may have also influenced the development of Chhinnamasta. These goddesses are mainly depicted headless to focus on the display of their sexual organs, thus signifying sexual vigour, but they do not explain the self-decapitation theme. The beheading and rejoining motif also appears in the tale of goddess Renuka.

Other Hindu goddesses which might have inspired Chhinnamasta are the malevolent war goddess Kotavi and the South-Indian hunting goddess Korravai. Kotavi, sometimes described as a Matrika ("mother goddess") is nude, dishevelled, wild and awful in appearance. She is mentioned in the scriptures Vishnu Purana and Bhagavata Purana, often as a foe of god Vishnu. The ferocious, wild Korravai is the goddess of war and victory. Both these goddesses are linked to battlefields, while Chhinnamasta is not. Kinsley says that there are several blood-thirsty, nude and wild goddesses and demonesses in Hindu mythology, though Chhinnamasta is the only goddess which displays the shocking self-decapitation motif.

Legends and textual references

Chhinnamasta is often named as the fifth or sixth Mahavidya in the group, with hymns identifying her as a fierce aspect of the Goddess. Kinsley says three Mahavidyas – Kali, Tara and Chhinnamasta — are prominent among Mahavidya depictions and lists, though Chhinnamasta hardly has an independent existence outside the group. The Guhyatiguhya-Tantra equates god Vishnu's ten avatars with the ten Mahavidyas; the man-lion incarnation Narasimha is described to have arisen from Chhinnamasta. A similar list in Mundamala equates Chhinnamasta with Parshurama.

In a story from the Shakta Maha-Bhagavata Purana and the Brihaddharma Purana, which narrates the creation of all Mahavidyas including Chhinnamasta, Sati, the daughter of Daksha and the first wife of the god Shiva, feels insulted that she and Shiva are not invited to Daksha's yagna ("fire sacrifice") and insists on going there, despite Shiva's protests. After futile attempts to convince Shiva, the enraged Sati assumes a fierce form, transforming into the Mahavidyas, who surround Shiva from the ten cardinal directions. As per the Shakta Maha-bhagavata Purana, Chhinnamasta stands to the right of Shiva, interpreted as the east or the west; the Brihaddharma Purana mentions she appears to the rear of Shiva in the west. Similar legends replace Sati with Parvati, the second wife of Shiva and reincarnation of Sati or Kali, the chief Mahavidya, as the wife of Shiva and origin of the other Mahavidyas. While Parvati uses the Mahavidyas to stop Shiva from leaving her father's house, Kali enlightens him and stops him, who was tired living with her, from leaving her. The Devi Bhagavata Purana also mentions the Mahavidyas as war-companions and forms of the goddess Shakambhari.

The Pranotasani Tantra narrates two tales of Chhinnamasta's birth. One legend, attributed to the Narada-pancharatra tells that once, while having a bath in Mandakini river, Parvati becomes sexually excited, turning her black. At the same time, her two female attendants Dakini and Varnini (also called Jaya and Vijaya) become extremely hungry and beg for food. Though Parvati initially promises to give them food once they return home, later the merciful goddess beheaded herself by her nails and gave her blood to satiate their hunger. Later, they returned home. The other variant from Pranotasani Tantra, attributed to Svatantra-tantra, is narrated by Shiva. He recounts that his consort Chandika (identified with Parvati) was engrossed in coitus with him in reverse posture, but became enraged at his seminal emission. Her attendants Dakini and Varnini rose from her body. The rest of the tale is similar to the earlier version, although the river is called Pushpabhadra, the day of Chhinnamasta's birth is called Viraratri and seeing the pale Parvati, Shiva becomes infuriated and assumes the form Krodha Bhairava. This version is retold in the Shaktisamgama-tantra where Chinnamasta forms a triad with Kali and Tara.

An oral legend records the goddess Prachanda-Chandika appeared to aid the gods in the god-demon war, when the gods prayed to the Great Goddess Mahashakti. After slaying all demons, the enraged goddess cut off her own head too and drank her own blood. The name Prachanda-Chandika also appears as a synonym of Chhinnamasta in her hundred-name hymn in the Shakta-pramoda. Another oral legend relates her to the Samudra manthan (Churning of Ocean) episode, where the gods and demons churned the milk ocean to acquire the amrita (the elixir of immortality). Chhinnamasta drank the demons' share of the elixir and then beheaded herself to prevent them from acquiring it.

The central themes of the mythology of Chhinnamasta are her self-sacrifice – with a maternal aspect (in the Pranotasani Tantra versions) or for the welfare of the world (in oral version 2) – her sexual dominance (second Pranotasani Tantra version) and her self-destructive fury (in oral legend 1).

Iconography

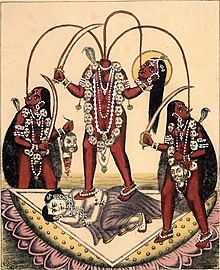

The iconography of Chinnamasta is described in the Tantrasara (late 16th century; Prachandachandika section), the Trishakti Tantra, the Shakta-pramoda(19th century; Chinnamastatantra section) and the Mantramahodadhi (1589 CE).

Chhinnamasta is described as being as red as the hibiscus flower or as bright as a million suns. She is usually depicted red or orange in complexion and sometimes as black. She is depicted mostly nude; however she is so posed that her genitals are generally hidden or a multi-hooded cobra or jewellery around the waist does the job. She is depicted young and slim. She is described to be a sixteen-year-old girl with full breasts, adorned with lotuses or having a single blue lotus near her heart.Sometimes, she is partially or fully clothed.

The goddess carries her own severed head – sometimes in a platter or a skull-bowl – in her left hand. In her right hand, she holds a khatri, a scimitar or knife or scissor-like object, by which she decapitated herself, even though no legend mentions any specific weapon for the beheading.Though generally depicted two-armed, four-armed manifestations of the goddess also exist. While her own severed head and the sword appear in two of her hands, the implements in the remaining arms vary: a scissor-like object, a skull-bowl collecting the dipping blood from her head or blood stream from her neck or a severed head, sometimes identified as that of god Brahma.

Chhinnamasta may have a lolling tongue. Her hair is loose and dishevelled and sometimes decorated with flowers. Alternately, in some images, her hair is tied. Additionally, she is described as three-eyed, with a jewel on her forehead, which is tied to a snake or a crown on the severed head. The crescent moon may also adorn her head. Chhinnamasta is depicted wearing a serpent as a sacred thread and a garland of skulls/severed heads and bones, along with other various gold or pearl ornaments around her neck. Bangles and waist-belt ornaments may be also depicted. She may also wear a snake around her neck and serpentine earrings. Three streams of blood string from her neck, one enters her own mouth, while the others are drunk by her female yogini companions, who flank her.

Both the attendants – Dakini to her left and Varnini to her right – are depicted nude, with matted or dishevelled hair, three-eyed, full-breasted, wearing the serpentine sacred thread and garland of severed heads, and carrying the skull-bowl in the left hand and the knife in the right. Sometimes, the attendants also hold severed heads (not their own). While Dakini is fair, Varnini is red-complexioned. In other depictions, both are depicted blue-grey. Sometimes, her attendants are depicted as skeletons and drinking the dripping blood from her severed head, rather than her neck. The attendants are absent in some depictions.

With her right leg stretched and left leg bent a little (pratyalidha stance), Chhinnamasta stands in a fighting posture on the love-deity couple of Kamadeva (Kama) – a symbol of sexual lust – and his wife Rati, who are engrossed in copulation with the latter usually on the top (viparita-rati sex position). Kamadeva is generally blue-complexioned, while Rati is white. Below the couple is a lotus with an inverted triangle and in the background is a cremation ground. The Chhinnamasta Tantra describes the goddess sitting on the couple, rather than standing on them. Sometimes, Kamadeva-Rati is replaced by the divine couple of Krishna and Radha. The lotus beneath the couple is sometimes replaced by a cremation pyre. The coupling couple is sometimes omitted completely. Sometimes, Shiva – the goddess's consort – is depicted lying beneath Chhinnamasta, who is seated squatting on him and copulating with him. Dogs or jackals drinking the blood sometimes appear in the scene. Sometimes, she directly stands on a lotus, a grass patch or the ground.

Another form of the goddess in the Tantrasara describes her seated in her own navel, formless and invisible. This form is said to be only realised via a trance. Another aniconic representation of the goddess is her yantra, which figures the inverted triangle and lotus found in her iconography.

The scholar van Kooij notes that the iconography of Chhinnamasta have the elements of heroism (vira rasa) and terror (bhayanaka rasa) as well as eroticism (sringara rasa) in terms of the copulating couple, with the main motifs being the offering of her own severed head, the spilling and drinking of blood and the trampling of the couple.

Chhinnamasta's popular iconography is similar to the yellow coloured severed-head form of the Buddhist goddess Vajrayogini, except the copulating couple – which is exclusive to the former's iconography – and Chhinnamasta's red skin tone.

Symbolism and associations

Goddess of paradoxes

- Ganapati Muni, Prachanda Chandika 9-11, 14Though her head is cut off, she is the support of life. Though she is frightening in appearance, she is the giver of peace. Though a maiden she increases our vigor, Mother Prachanda Chandika.

Chinnamasta is a goddess of contradictions: dichotomies of giver and taker, subject and object, and food and eater dissolve in her iconography. Most of her epithets listed in her namastotra (name-hymn) convey marvel and fury; few names are also erotic and peaceful, which is contrary to Chhinnamasta's fierce nature and appearance. Her thousand name-hymn echoes paradoxes; she is Prachanda-Chandika ("the powerfully fierce one") as well as Sarvananda-pradayini ("the prime giver of all ananda or bliss"). Her names convey that though she is fierce at first appearance, she can be gentle on worship.

While other fierce Hindu goddesses like Kali are depicting severing the heads of demons and are associated with ritual self-decapitation, Chhinnamasta's motif also reverses ritual head-offering, in which she offers her own head to the devotees (attendants) to feed them. In this way, she symbolizes the aspect of the Goddess as a giver like Annapurna, the goddess of food and Shakambhari, the goddess of vegetables, or a maternal aspect. The self-sacrifice is the symbol of "divine reciprocation" by the deity to her devotees. As a self-sacrificing mother, she symbolises the ideal Indian woman; however her sexuality and power are at odds with the archetype. She subdues and takes the life-force of the copulating divine couple, signifying the aspect of the life-taker like Kali.

Chhinnamasta's serpentine ornaments indicate asceticism; while her youthful nude ornamented body has erotic overtones. Like all Hindu goddesses, she is decked up in gold finery, symbol of wealth and fertility.

Destruction, Transformation and Recreation

The scholar P. Pal as well as Bhattacharya equates Chhinnamasta with the concept of sacrifice and renewal of creation. Chhinnamasta self-sacrifices herself; her blood – drunk by her attendants – nourishes the universe. An invocation to her calls her the sacrifice, the sacrificer and the recipient of the sacrifice, with the severed head treated as an offering. This paradox signifies the entire sacrificial process, there by the cycle of creation, dissolution and re-creation.

Chhinnamasta is "a figure of radical transformation, a great yogini". She conveys the universal message that all life sustains on other forms of life, and destruction and sacrifice are necessary for continuity of creation. The goddess symbolizes pralaya (cosmic dissolution), where she swallows all creation and makes way for new creation; thus conveys the idea of transformation. The Goddess is said to assume the form of Chinnamasta for destruction of the universe. Chhinnamasta is considered a fearsome aspect of the Goddess and included among the Kalikula ("family of Kali") goddesses. She is said to represent Transformation and complements Kali, who stands for Time. Her hundred-name hymn and thousand-name hymn describe her fierce nature and wrath. The names describe her as served by ghosts and as gulping blood. She is pleased by human blood, human flesh and meat, and worshipped by body hair, flesh and fierce mantras.

The head offering and subsequent restoration of the head signifies immortality. The dichotomy of temporality and immortality is alluded to by the the blood stream drunk by Chhinnamasta's head - interpreted as amrita (elixir of life) and the serpent, which sheds its skin without dying. The skull and several head garland signifies her victory over Time and fear of Death. Chhinnamasta's black complexion denotes destruction; in contrast to her depiction as red or orange that denotes life. By drinking the blood, she appears as the Saviour, who drinks the negativities of the world and transforms it to beneficent energies; in this interpretation, the blood is seen in negative light rather than amrita.

Chhinnamasta signifies that life, death and sex are interdependent. Her image conveys the eternal truth that "life feeds on death, is nourished by death, necessitates death, and that the ultimate destiny of sex is to perpetuate more life, which in turn will decay and die in order to feed more life". While the lotus and the lovemaking couple symbolize life and the urge to create life, in a way gives life-force to the beheaded goddess, the blood flowing from goddess conveys death and loss of the life-force, which flows into the mouths of her devotee yoginis, nourishing them.

Self-realization and Awakening of Kundalini

The head is celebrated as a mark of identity as well as source of the seed. Thus, the self-decapitation represents removal of maya (illusion or delusion), physical attachment, false notions, ignorance and egoism. The scimitar also signifies severance of these obstacles to moksha (emancipation), jnana (wisdom) and self-realization. The goddess also denotes discriminating perception. Chhinnamasta allows the devotee to gain consciousness that transcends the bonds of physical attachment, the body and the mind by her self-sacrifice. While an interpretation suggests her three eyes represent the sun, the moon and fire; another links the third eye to transcendental knowledge. Unlike other Hindu deities who are depicted looking at the devotee, Chhinnamasta generally looks at herself, prompting the devotee to look within himself.

The Chhinnamasta icon is also understood as a representation of the awakening of the kundalini – spiritual energy. The copulating couple represent the awakening in the Muladhara chakra, which corresponds to the last bone in the spinal cord. The kundalini flows through the central passage in the body – the Sushumna nadi and hitting the topmost chakra, the Sahasrara at the top of head – with such force that it blows her head out. The blood spilling from the throat applies the upward-flowing kundalini, breaking all knots (granthis) – which make a person sad, ignorant and weak – of the chakras. The severed head is "transcendent consciousness". The three blood streams is the flow of nectar when the kundalini unites with Shiva, who resides in the Sahasrara. The serpent in her iconography is also a symbol of the kundalini.

Another interpretation associates Daknini, Varnini and Chhinnamasta with the three main subtle channels (nadis): Ida, Pingala and Sushumna - respectively - flowing free. The goddess is generally said to be visualized in one's navel, the location of the Manipura chakra where the three nadis unite and symbolizes consciousness as well as the duality of creation and dissolution.

The ability to remain alive despite the beheading is associated to supernatural powers and awakening of the kundalini. The Earl of Ronaldshay (1925) compared Chhinnnamasta to India, beheaded by the British, "but nevertheless preserving her vitality unimpaired by drinking her own blood".

Control over or Embodiment of sexual desire

Chhinnamasta standing on a copulating couple of Kamadeva (literally "sexual desire") and Rati ("sexual intercourse") is interpreted by some as a symbol of self-control of sexual desire, while others interpret it as the goddess, being an embodiment of sexual energy. Her names like Yogini and Madanatura ("one who has control on Kama") convey her yogic control and restraint on sexual energy. Her triumphant stance trampling the love-deity couple denotes his victory over desire and samsara (the cycle of birth, death and re-birth).

Images in which Chhinnamasta is depicted sitting on Kamadeva-Rati in a non-suppressive fashion, the couple giving sexual energy to the goddess. Images where Shiva is depicted in coitus with Chhinnamasta are associated with this interpretation. Chhinnamasta's names like Kameshwari ("goddess of desire") and Ratiragavivriddhini ("one who is engrossed in the realm of Rati – ") and the appearance of klim – the common seed syllable of Kamadeva and Krishna – in her mantra support this interpretation. Her lolling tongue also denotes sexual hunger.

The inverted triangle, found in Chhinnamasta's iconography as well as in her yantra, signifies the womb (yoni) and the feminine. The goddess is often prescribed to be visualized in the centre of the inverted triangle in the navel. It also signifies the three gunas and three shaktis (powers) - iccha ("will-power"), kriya ("action") and jnana (wisdom). The goddess is called Yoni-mudra or Yoni-gamya, accessible through the yoni.

Other symbolism and associations

Chhinnamasta's nudity and headlessness symbolise her integrity and "heedlessness". Her names like Ranjaitri ("victorious in war") celebrate her as the slayer of various demons and her prowess in battle. Her nakedness and dishevelled hair denote rejection of societal values and her rebellious freedom, as well as her sensual aspect.

The triad of the goddess and the two yoginis is also philosophically cognate to the triad of patterns, "which creative energy is felt to adopt". Besides the nadis, Chhinnamasta, Varnini and Dakini also represent the guna trinity: sattva (purity), rajas (energy) and tamas (ignorance). While discussing Mahavidya as a group, Chinnamasta is associated with rajas (in the Kamadhenu-Tantra and the Maha-nirvana-Tantra) or sattva (based on her lighter complexion).

While the goddess is a mature sixteen-year old who has conquered her ego and awakened her kundalini, the attendants are described as spiritually immature twelve-year olds, who sustain on the goddess' blood and are not liberated from the delusion of duality. In portrayals where the goddess' hair are tied like a matron and her attendants have free-flowing hair like young girls, the goddess is treated as a motherly figure of regal authority and power; the tied hair and headlessness represent contrasting ideas of controlled and uncontrolled nature respectively.

Chhinnamasta's association with the navel and her red complexion also connects to the fire element and the sun; while the lotus in her iconography signifies purity.

Worship

While she is easily identified by most Hindus and often worshipped and depicted as part of the Mahavidya group in goddess temples, Chhinnamasta's individual cult is not widespread. Though her individual temples as well as her public worship are rare, Chinnamasta is an important deity in Tantric worship. She enjoys active worship in eastern India and Nepal. Her individual worship is mainly restricted to heroic, Tantric worship by Tantrikas (a type of Tantric practitioners), yogis and world renouncers. The lack of her worship by lay worshippers is attributed by Kinsley to her ferocious nature and her reputation of being dangerous to approach and worship.

Goals of worship

Tantric practitioners worship Chhinnamasta for acquiring siddhis or supernatural powers. Chhinnamasta's mantra Srim hrim klim aim Vajravairocaniye hum hum phat svaha is to be invoked to attract and subjugate women. Her mantra associates her with syllables denoting beauty, light, fire, spiritual self-realization and destruction of delusion. The Shakta-pramoda and the Rudrayamala recommends the use of her mantra to gain wealth and auspiciousness. Another goal of her worship is to cast spells and cause harm to someone. Acarya Ananda Jha, the author of the Chinnamasta Tattva, prescribes her worship by soldiers as she embodies self-control of lust, heroic self-sacrifice for the benefit of others and fearlessness of death. In a collective prayer to the mahavidyas in the Shakta Maha-bhagavata Purana, the devotee prays to emulate Chhinnamasta in her generosity to others. Other goals common to worship of all mahavidyas are: poetic speech, well-being, control of one's foes, removal of obstacles, ability to sway kings, ability to attract others, conquest over other kings and finally, moksha (salvation).

Modes of worship

The Tantric texts Tantrasara,Shakta-pramoda and Mantra-mahodadhih give details about the worship of Chhinnamasta and other Mahavidyas, including her yantra, mantra and her meditative/iconographic forms (dhyanas). In her puja, her image or her yantra is worshipped, along with her attendants. The heterodox offerings of Panchamakara - wine, meat, fish, parched grain and coitus; along with mainstream offerings like flowers, light, incense etc. are prescribed for her worship. A fire sacrifice and repetition of her stotra (hymn of praise) or her nama-stotra (name-hymn) are also prescribed in her worship. The Shakta-pramoda has her sahasranama (1000 name-hymn) as well as a compilation of her 108 names in a hymn.

Tantric texts tells the worshipper to imagine a red sun orb – signifying a yoni triangle – in his own navel. In the orb, the popular form of Chhinnamasta is imagined to reside. The Tantrasara cautions a householder-man to invoke the goddess only in "abstract terms". It further tells that if woman invokes Chhinnamasta by her mantra, the woman will become a dakini and lose her husband and son, thereby becoming a perfect yogini. TheShaktisamgama-tantra prescribes her worship only by the left-handed path (Vamamarga). The Mantra-mahodadhih declares that such worship involves having sexual intercourse with a woman, who is not one's wife. The Shakta-pramoda tells the same, adding fire sacrifices, wine and meat offerings at night. The best time to propitiate her is said to be the fourth quarter of the evening, that is, midnight.

Some hymns narrate that Chinnamasta likes blood and as such, is offered blood sacrifices at some shrines. The Shaktisamgama-tantra says that only brave souls (viras) should follow Vamamarga worship to the goddess. The Shakta-pramoda warns that improper worship would have severe consequences: Chhinnamasta would behead such a person and drink his blood. It further categorizes worship for Chhinnamasta to be followed by householders and renouncers. The Todala Tantra mentions that Shiva or his fierce form Bhairava be worshipped as Kabandha ("headless trunk") as the goddess' consort in her worship.

Chinnamasta is often worshipped at midnight along with the other mahavidyas at Kali Puja, the festival of Kali. However, householders are precautioned not to worship her.

Temples

The Chintpurni ("She who fulfills one’s wishes"), Himachal Pradesh temple of Chhinnamastika is one of the Shakti Peethas and where the goddess Sati's forehead (mastaka) fell. Here, Chhinnamasta is interpreted as the severed-headed one as well as the foreheaded-one. The central icon is a pindi, an abstract form of the Goddess. While householders worship the goddess as a form of the goddess Durga; ascetic sadhus view her as the Tantric severed headed goddess.

Another important shrine is the Chhinnamasta Temple near Rajrappa in Jharkhand, where a natural rock covered with an ashtadhatu (eight-metal alloy) kavacha (cover) is worshipped as the goddess. Though well-established as a centre of Chhinnamasta by 18th century, the site is a popular place of worship among tribals since ancient times. Kheer and animal sacrifice is offered to the goddess.

A shrine dedicated to Chhinnamasta is built by a Tantric sadhu in the Durga Temple complex, Ramnagar, near Varanasi, where tantrikas worship her using corpses. There are Chhinnamasta shrines on the hill Nandan Parvat near Deoghar (Vaidyanath) and Bishnupur, West Bengal. Her shrine is also situated in the Kamakhya Temple complex, Assam, along with other Mahavidyas. In Bengal, Chinnamasta is a popular goddess. The goddess Manikeswari, a popular goddess in Odisha is often identified with Chhinnamasta.

Chhinnamasta's shrines are also found in Nepal's Kathmandu Valley. A shrine in the Changu Narayan Temple holds a thirteenth century icon of Chinnamasta. A chariot festival in the Nepali month of Baishakh is celebrated is in honour of the goddess. Near the Temple, a small shrine in the fields also exists. A 1732 temple of the goddess in Patan contains her images in different postures and enjoys active worship.

See also

- Devi

- Mahavidya

- Cephalophore: Christian saints depicted holding their own severed heads

Footnotes

- Explanatory Notes

- ^ Sushumna connects the Muladhara and Sahasrara and is cognate with the spinal cord. Ida courses from the right testicle to the left nostril and is linked to the cooling lunar energy and the right hand side of the brain. Pingala courses from the left testicle to the right nostril and is associated with the hot solar energy and the left hand side of the brain.

- Citations

- Kinsley (1988, p. 172)

- Benard (2000, pp. 9–11)

- Benard (2000, pp. 12–5)

- ^ Benard (2000, pp. 16–7)

- ^ Donaldson (2001, p. 411)

- ^ Kinsley (1988, p. 175)

- van Kooij (1999, p. 266)

- ^ Kinsley (1988, p. 176)

- Mishra, Mohanty & Mohanty (2002, p. 315)

- Storm (2013, p. 296)

- ^ Kinsley (1988, p. 177)

- Kinsley (1997, pp. 144–7)

- ^ Kinsley (1988, p. 165)

- Foulston & Abbott (2009, p. 120)

- ^ Storm (2013, p. 287)

- ^ McDaniel (2004, p. 259)

- ^ Frawley (1994, p. 112)

- Kinsley (1997, pp. 2, 5, 9)

- Kinsley (1988, p. 161)

- Benard (2000, p. 5)

- ^ Kinsley (1988, p. 162)

- Kinsley (1997, p. 23)

- Benard (2000, pp. 1–3)

- R Mahalakshmi (2014, p. 201)

- Gupta (2000, p. 470)

- Kinsley (1997, pp. 28–29)

- Kinsley (1997, p. 31)

- ^ Donaldson (2001, p. 412)

- Kinsley (1997, pp. 147–8)

- ^ Kinsley (1997, p. 148)

- ^ R Mahalakshmi (2014, p. 202)

- Gupta (2000, p. 464)

- Kinsley (1997, p. 21)

- Kinsley (1997, pp. 149–50)

- ^ Benard (2000, p. 23)

- Benard (2000, p. 84)

- ^ Benard (2000):

- pp. 33-4, 36-7, 47: Shakta-pramoda

- p. 86: Mantramahodadhi

- pp. 87: Tantrasara

- ^ Kinsley (1988, p. 173)

- ^ Kinsley (1997, p. 144)

- ^ van Kooij (1999, p. 258)

- ^ Storm (2013, pp. 289–96)

- * Storm (2013, p. Cover page)

- Monastery, Kauai's Hindu. "Art & Photos - Chinnamasta - Mahavidya". www.himalayanacademy.com. Retrieved 2016-06-26.

- ^ R Mahalakshmi (2014, p. 203)

- ^ Bhattacharya Saxena (2011, pp. 65–6)

- ^ Donaldson (2001, p. 413)

- Kinsley (1997, p. 11)

- ^ R Mahalakshmi (2014, p. 204)

- Storm (2013, p. 295)

- van Kooij (1999, pp. 255, 264)

- ^ Benard (2000, pp. 8–9)

- Benard (2000, pp. 58–61)

- Bhattacharya Saxena (2011, pp. 69–70)

- Storm (2013, p. 286)

- Storm (2013, pp. 286–7)

- Storm (2013, p. 293)

- Kinsley (1997, p. 50)

- Benard (2000, p. xv)

- van Kooij (1999, p. 252)

- Frawley (1994, pp. 116–7)

- Kinsley (1997, p. 41)

- ^ McDaniel (2004, p. 91)

- Frawley (1994, p. 154)

- Frawley (1994, p. 153)

- ^ Kinsley (1997, p. 164)

- Benard (2000, pp. 99–100, 101–5, 108)

- ^ Storm (2013, p. 294)

- Benard (2000, pp. 101–2)

- Frawley (1994, p. 115)

- Kinsley (1997, pp. 157–9)

- Benard (2000, pp. 93–95)

- Benard (2000, pp. 107–108)

- ^ Kinsley (1997, pp. 163–4)

- Storm (2013, p. 302)

- Frawley (1994, pp. 153, 203)

- Frawley (1994, pp. 112–5)

- Benard (2000, pp. 100–101)

- ^ Kinsley (1997, pp. 159–61)

- ^ van Kooij (1999, pp. 249–50)

- Frawley (1994, p. 117)

- Benard (2000, pp. xii–xiii)

- Benard (2000, pp. 88–9)

- Benard (2000, p. 97)

- Storm (2013, pp. 294–5)

- Kinsley (1997, p. 154)

- Benard (2000, pp. 105–6)

- Kinsley (1997, pp. 155–7)

- Benard (2000, pp. 34, 90–1)

- Bhattacharya Saxena (2011, p. 69)

- ^ Kinsley (1997, p. 155)

- Benard (2000, pp. 106–7)

- ^ Storm (2013, p. 292)

- ^ Benard (2000, pp. 108–10)

- Kinsley (1997, p. 42)

- Benard (2000, pp. 89–90, 92–3)

- Lochtefeld (2002, p. 149)

- Bhattacharya Saxena (2011, p. 64)

- Kinsley (1997, p. 157)

- Benard (2000, p. 34)

- Frawley (1994, p. 119)

- ^ R Mahalakshmi (2014, p. 205)

- Kinsley (1997, p. 220)

- van Kooij (1999, p. 260)

- Benard (2000, pp. 25–33)

- Benard (2000, pp. 58–60)

- Benard (2000, pp. 121–44, Appendix 1)

- ^ Kinsley (1997, pp. 165–6)

- Kinsley (1997, p. 147)

- Gupta (2000, p. 467)

- ^ Mishra, Mohanty & Mohanty (2002, pp. 319–20)

- Bhattacharya Saxena (2011, p. 65)

- ^ Lochtefeld (2002, pp. 149–50)

- Benard (2000, pp. 4, 145)

- Benard (2000, p. 146)

- R Mahalakshmi (2014, pp. 206–13)

- Benard (2000, pp. 145–6)

- Benard (2000, pp. 146–7)

- Satapathy (2009, p. 90)

- ReedMc & Connachie (2002, p. 235)

- Benard (2000, pp. 147)

References

- Bhattacharya Saxena, Neela (2011). "Mystery, Wonder, and Knowledge in the Triadic Figure of Mahāvidyā Chinnamastā: A Śākta Woman's Reading". In Pintchman, Tracy; Sherma, Rita D. (eds.). Woman and Goddess in Hinduism: Reinterpretations and Re-envisionings. Palgrave Macmillan US. ISBN 978-1-349-29540-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Benard, Elizabeth Anne (2000), Chinnamasta: The Aweful Buddhist and Hindu Tantric Goddess, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1748-7

- Donaldson, Thomas E. (2001), Iconography of the Buddhist Sculpture of Orissa, New Delhi: Indira Gandhi Nation Centre for Arts (Abhinav Publications), pp. 411–3, ISBN 978-81-7017-406-6

- Foulston, Lynn; Abbott, Stuart (2009). Hindu Goddesses: Beliefs and Practices. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 9781902210438.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Frawley, David (1994), Tantric Yoga and the Wisdom Goddesses: Spiritual Secrets of Ayurveda, Lotus Press, ISBN 978-0-910261-39-5

- Gupta, Sanjukta (2000), "The Worship of Kali According to the Todala Tantra", in White, David Gordon (ed.), Tantra in Practice, ISBN 0-691-05779-6

- Kinsley, David R. (1988), "Tara, Chinnamasta and the Mahavidyas", Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition (1 ed.), University of California Press, pp. 161–177, ISBN 978-0-520-06339-6 (1998 edition depicts Chhinnamasta on the front page)

- Kinsley, David R. (1997), Tantric visions of the divine feminine: the ten mahāvidyās, University of California Press., ISBN 978-0-520-20499-7 (This edition depicts Chhinnamasta on the front page)

- Lochtefeld, James G., ed. (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Vol. 1. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. ISBN 0-8239-2287-1.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - Mishra, Baba; Mohanty, Pradeep; Mohanty, P. K. (2002). "HEADLESS CONTOUR IN THE ART TRADITION OF ORISSA, EASTERN INDIA". Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. 62/63: 311–21. JSTOR 42930626.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McDaniel, June (2004), Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls : Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal: Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-516791-0

- Reed, David; McConnachie, James (2002). The Rough Guide to Nepal. Rough Guides. ISBN 9781858288994.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Satapathy, Umesh Chandra (September 2009). "Chhatra Yatra of Manikeswari" (PDF). Orissa Review. Government of Odisha: 90.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - R Mahalakshmi (2014), "Tantric Visions, Local Manifestations: The Cult Center of Chinnamasta at Rajrappa, Jharkhand", in Sree Padma (ed.), Inventing and Reinventing the Goddess: Contemporary Iterations of Hindu Deities On the Move, Lexington Books, ISBN 978-0-7391-9001-2

- Storm, Mary (2013), Head and Heart: Valour and Self-Sacrifice in the Art of India, New Delhi: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-81246-7 (This edition depicts Chhinnamasta on the front page)

- van Kooij, Karel R. (1999), "Iconography of the Battlefield: The Case of Chinnamasta", in Houben, Jan E. M.; van Kooij, Karel R. (eds.), Violence Denied, BRILL, ISBN 90-04-11344-4

| Shaktism | ||

|---|---|---|

| Devi |  | |

| Matrikas | ||

| Mahavidya | ||

| Navadurga | ||

| Shakta pithas | ||

| Texts | ||

| Regional variations | ||

| Hindu deities and texts | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gods |  | |

| Goddesses | ||

| Other deities | ||

| Texts (list) | ||

Categories: