| Revision as of 01:57, 19 January 2017 editYSSYguy (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers33,400 edits Undid revision 760652167 by 203.26.123.208 (talk);I have done a lot of aircraft marshalling; I have never used a radio and use of a mobile 'phone is prohibited← Previous edit | Revision as of 05:40, 24 January 2017 edit undo203.26.123.208 (talk) There are hundreds of aircraft marshallers in the world. You are not the only one.Next edit → | ||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

| {{unreferenced section|date=January 2016}} | {{unreferenced section|date=January 2016}} | ||

| ]]] | ]]] | ||

| Marshalling is one-on-one visual communication and a part of ]. It may be as an alternative to, or additional to, radio communications between the aircraft and ]. The usual equipment of a marshaller is a reflecting ], a helmet with acoustic ]s, and gloves or marshaling wands–handheld illuminated ]s. | Marshalling is one-on-one visual communication and a part of ]. It may be as an alternative to, or additional to, radio communications between the aircraft and ]. The usual equipment of a marshaller is a reflecting ], a helmet with acoustic ]s, and gloves or marshaling wands–handheld illuminated ]s. They also have a mobile phone or radio to communicate with other staff. | ||

| At airports, the marshaller signals the pilot to keep turning, slow down, stop, and shut down engines, leading the aircraft to its parking stand or to the ]. Sometimes, the marshaller indicates directions to the pilot by driving a "Follow-Me" car (usually a yellow ] or pick-up truck with a checkerboard pattern) prior to disembarking and resuming signalling, though this is not an industry standard. | At airports, the marshaller signals the pilot to keep turning, slow down, stop, and shut down engines, leading the aircraft to its parking stand or to the ]. Sometimes, the marshaller indicates directions to the pilot by driving a "Follow-Me" car (usually a yellow ] or pick-up truck with a checkerboard pattern) prior to disembarking and resuming signalling, though this is not an industry standard. | ||

Revision as of 05:40, 24 January 2017

Aircraft marshalling is visual signalling between ground personnel and pilots on an airport, aircraft carrier or helipad.

Activity

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Marshalling is one-on-one visual communication and a part of aircraft ground handling. It may be as an alternative to, or additional to, radio communications between the aircraft and air traffic control. The usual equipment of a marshaller is a reflecting safety vest, a helmet with acoustic earmuffs, and gloves or marshaling wands–handheld illuminated beacons. They also have a mobile phone or radio to communicate with other staff.

At airports, the marshaller signals the pilot to keep turning, slow down, stop, and shut down engines, leading the aircraft to its parking stand or to the runway. Sometimes, the marshaller indicates directions to the pilot by driving a "Follow-Me" car (usually a yellow van or pick-up truck with a checkerboard pattern) prior to disembarking and resuming signalling, though this is not an industry standard.

At busier and better equipped airports, marshallers are replaced on some stands with a Visual Docking Guidance System (VDGS), of which there are many types.

On aircraft carriers or helipads, marshallers give take-off and landing clearances to aircraft and helicopters, where the very limited space and time between take-offs and landings makes radio communications a difficult alternative.

U.S Air Force procedures

Per the most recent U.S Air Force marshalling instructions from 2012, marshallers "must wear a sleeveless garment of fluorescent international orange. It covers the shoulders and extends to the waist in the front and back. During daylight hours, marshallers may use high visibility paddles. Self-illuminating wands are required at night or during restricted visibility."

Marshallers like other ground personnel must use protective equipment like protective goggles or "an appropriate helmet with visor, when in rotor wash areas or in front of an aircraft that is being backed using the aircraft's engines."

It also prescribes "earplugs, muff-type ear defenders, or headsets in the immediate area of aircraft that have engines, Auxiliary Power Unit, or Gas Turbine Compressor running."

Noise exposure

Excessive noise can cause hearing loss in marshallers, either imperceptibly over years or after a one time acoustic trauma. In the United States noise limits at work are set by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).

Aircraft signals

| This section's factual accuracy is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help to ensure that disputed statements are reliably sourced. (May 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Aircraft signals vary slightly among the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Standardization Agreement 3117, Air Standardization Coordinating Committee Air Standard 44/42A, the Appendix 1 of the Annex 2 to the Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation, and Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) signals. the US Air Force generally follows ICAO guidance if its guidance conflicts with FAA, ICAO, or NATO documents. The ICAO defines numerous important codes for use in international aviation.

-

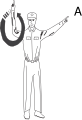

All clear

All clear

-

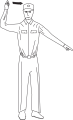

Flagman directs pilot (stop)

Flagman directs pilot (stop)

-

Insert chocks

Insert chocks

-

Pull chocks

Pull chocks

-

Start engines

Start engines

-

Cut engines

Cut engines

-

Proceed straight ahead

Proceed straight ahead

-

Turn left

Turn left

-

Turn right

Turn right

-

Slow down

Slow down

-

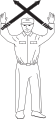

Stop (emergency stop)

Stop (emergency stop)

Helicopter signals

| This section's factual accuracy is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help to ensure that disputed statements are reliably sourced. (May 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

-

Lift off

Lift off

-

Land

Land

-

Move upward

Move upward

-

Move downward

Move downward

-

Move left

Move left

-

Move right

Move right

-

Move forward

Move forward

-

Move rearward

Move rearward

-

Hold hover

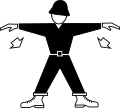

Hold hover

-

Release sling load

Release sling load

References

- ^ U.S Air Force Flying Operations and Movement on the Ground Flight Rules and Procedures. AIR FORCE INSTRUCTION 11-218, 28 October 2011, Incorporating Change 1, 1 November 2012, 89 pp

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) FAA Webtraining Environment Human Factors Awareness Course, n.d., accessed 7 January 2015.

- CAP637 Visual Aids Handbook; CAA; Issue 2, May 2007; Chapter 6, page 10, Table E