| Revision as of 08:14, 1 April 2017 editMoonlight vs lalaland (talk | contribs)33 edits Checked source and this fact was not detailed← Previous edit | Revision as of 08:17, 1 April 2017 edit undoMoonlight vs lalaland (talk | contribs)33 edits Add source material to prior editNext edit → | ||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

| === Irrational numbers === | === Irrational numbers === | ||

| While the ancient Indians had originally discovered ]s, the Greeks were not happy with them and only able to cope by drawing a distinction between ''magnitude'' and ''number''. In the Greek view, magnitudes varied continuously and could be used for entities such as line segments, whereas numbers were discrete. Hence, irrationals could only be handled geometrically; and indeed Greek mathematics was mainly geometrical. Islamic mathematicians including ] and ] slowly removed the distinction between magnitude and number, allowing irrational quantities to appear as coefficients in equations and to be solutions of algebraic equations.<ref name=Sesiano/><ref>{{MacTutor|id=Al-Baghdadi|title=Abu Mansur ibn Tahir Al-Baghdadi}}</ref> They worked freely with irrationals as mathematical objects, but they did not examine closely their nature.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Allen |first1=G. Donald |title=The History of Infinity |url=http://www.math.tamu.edu/~dallen/history/infinity.pdf |publisher=Texas A&M University |accessdate=7 September 2016 |date=n.d.}}</ref> | While the ancient Indians had originally discovered ]s<ref>{{cite journal |last=Bag |first=A.K. |title=Ritual Geometry in India and Parellelism in Other Cultural Areas |journal=Indian Journal of History of Science |volume=25 |issue=1-4 |year=1990}}</ref>, the Greeks were not happy with them and only able to cope by drawing a distinction between ''magnitude'' and ''number''. In the Greek view, magnitudes varied continuously and could be used for entities such as line segments, whereas numbers were discrete. Hence, irrationals could only be handled geometrically; and indeed Greek mathematics was mainly geometrical. Islamic mathematicians including ] and ] slowly removed the distinction between magnitude and number, allowing irrational quantities to appear as coefficients in equations and to be solutions of algebraic equations.<ref name=Sesiano/><ref>{{MacTutor|id=Al-Baghdadi|title=Abu Mansur ibn Tahir Al-Baghdadi}}</ref> They worked freely with irrationals as mathematical objects, but they did not examine closely their nature.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Allen |first1=G. Donald |title=The History of Infinity |url=http://www.math.tamu.edu/~dallen/history/infinity.pdf |publisher=Texas A&M University |accessdate=7 September 2016 |date=n.d.}}</ref> | ||

| In the twelfth century, ] translations of ]'s ] on the ] introduced the ] ] to the ].<ref name="Struik 93">{{harvnb|Struik|1987| p= 93}}</ref> His ''Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing'' presented the first systematic solution of ] and ]s. In ] Europe, he was considered the original inventor of algebra, although it is now known that his work is based on older Indian or Greek sources.<ref>{{harvnb|Rosen|1831|p=v–vi}}; {{harvnb|Toomer|1990}}</ref> He revised ]'s '']'' and wrote on astronomy and astrology. However, scholars such as ] suggest that al-Khwarizmi's original work was not based on Ptolemy but on a derivative world map,{{sfnp|Nallino|1939}} presumably in ] or ]. | In the twelfth century, ] translations of ]'s ] on the ] introduced the ] ] to the ].<ref name="Struik 93">{{harvnb|Struik|1987| p= 93}}</ref> His ''Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing'' presented the first systematic solution of ] and ]s. In ] Europe, he was considered the original inventor of algebra, although it is now known that his work is based on older Indian or Greek sources.<ref>{{harvnb|Rosen|1831|p=v–vi}}; {{harvnb|Toomer|1990}}</ref> He revised ]'s '']'' and wrote on astronomy and astrology. However, scholars such as ] suggest that al-Khwarizmi's original work was not based on Ptolemy but on a derivative world map,{{sfnp|Nallino|1939}} presumably in ] or ]. | ||

Revision as of 08:17, 1 April 2017

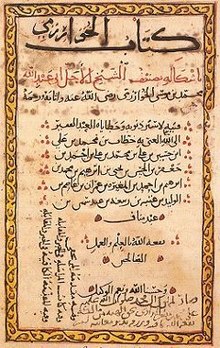

Mathematics during the Golden Age of Islam, especially during the 9th and 10th centuries, was built on Indian mathematics (Aryabhata, Brahmagupta) and Bhāskara I and Greek mathematics (Euclid, Archimedes, Apollonius). Important progress was made, such as the full development of the decimal place-value system to include decimal fractions, the first systematised study of algebra (named for The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing by scholar Al-Khwarizmi), and advances in geometry and trigonometry.

Arabic works also played an important role in the transmission of mathematics to Europe during the 10th to 12th centuries.

History

Algebra

Further information: History of algebraThe study of algebra, the name of which is derived from the Arabic word meaning completion or "reunion of broken parts", flourished during the Islamic golden age. Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, a scholar in the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, is along with the Greek mathematician Diophantus, known as the father of algebra. In his book The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing, Al-Khwarizmi deals with ways to solve for the positive roots of first and second degree (linear and quadratic) polynomial equations. He also introduces the method of reduction, and unlike Diophantus, gives general solutions for the equations he deals with.

Al-Khwarizmi's algebra was rhetorical, which means that the equations were written out in full sentences. This was unlike the algebraic work of Diophantus, which was syncopated, meaning that some symbolism is used. The transition to symbolic algebra, where only symbols are used, can be seen in the work of Ibn al-Banna' al-Marrakushi and Abū al-Ḥasan ibn ʿAlī al-Qalaṣādī.

On the work done by Al-Khwarizmi, J. J. O'Connor and Edmund F. Robertson said:

"Perhaps one of the most significant advances made by Arabic mathematics began at this time with the work of al-Khwarizmi, namely the beginnings of algebra. It is important to understand just how significant this new idea was. It was a revolutionary move away from the Greek concept of mathematics which was essentially geometry. Algebra was a unifying theory which allowed rational numbers, irrational numbers, geometrical magnitudes, etc., to all be treated as "algebraic objects". It gave mathematics a whole new development path so much broader in concept to that which had existed before, and provided a vehicle for future development of the subject. Another important aspect of the introduction of algebraic ideas was that it allowed mathematics to be applied to itself in a way which had not happened before."

— MacTutor History of Mathematics archive

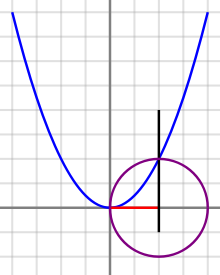

Several other mathematicians during this time period expanded on the algebra of Al-Khwarizmi. Omar Khayyam, along with Sharaf al-Dīn al-Tūsī, found several solutions of the cubic equation. Omar Khayyam found the general geometric solution of a cubic equation.

Cubic equations

Omar Khayyám (c. 1038/48 in Iran – 1123/24) wrote the Treatise on Demonstration of Problems of Algebra containing the systematic solution of cubic or third-order equations, going beyond the Algebra of al-Khwārizmī. Khayyám obtained the solutions of these equations by finding the intersection points of two conic sections. Khayyám differentiated between "geometric" and "arithmetic" solutions. Khayyám mistakenly believed arithmetic solutions only existed if the roots were positive and rational. Khayyám did not concern himself with numerical calculations of the solutions. -->

Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (? in Tus, Iran – 1213/4) developed a novel approach to the investigation of cubic equations—an approach which entailed finding the point at which a cubic polynomial obtains its maximum value. For example, to solve the equation , with a and b positive, he would note that the maximum point of the curve occurs at , and that the equation would have no solutions, one solution or two solutions, depending on whether the height of the curve at that point was less than, equal to, or greater than a. His surviving works give no indication of how he discovered his formulae for the maxima of these curves. Various conjectures have been proposed to account for his discovery of them.

Induction

See also: Mathematical induction § HistoryThe earliest implicit traces of mathematical induction can be found in Euclid's proof that the number of primes is infinite (c. 300 BCE). The first explicit formulation of the principle of induction was given by Pascal in his Traité du triangle arithmétique (1665).

In between, implicit proof by induction for arithmetic sequences was introduced by al-Karaji (c. 1000) and continued by al-Samaw'al, who used it for special cases of the binomial theorem and properties of Pascal's triangle.

Irrational numbers

While the ancient Indians had originally discovered irrational numbers, the Greeks were not happy with them and only able to cope by drawing a distinction between magnitude and number. In the Greek view, magnitudes varied continuously and could be used for entities such as line segments, whereas numbers were discrete. Hence, irrationals could only be handled geometrically; and indeed Greek mathematics was mainly geometrical. Islamic mathematicians including Abū Kāmil Shujāʿ ibn Aslam and Ibn Tahir al-Baghdadi slowly removed the distinction between magnitude and number, allowing irrational quantities to appear as coefficients in equations and to be solutions of algebraic equations. They worked freely with irrationals as mathematical objects, but they did not examine closely their nature.

In the twelfth century, Latin translations of Al-Khwarizmi's Arithmetic on the Indian numerals introduced the decimal positional number system to the Western world. His Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing presented the first systematic solution of linear and quadratic equations. In Renaissance Europe, he was considered the original inventor of algebra, although it is now known that his work is based on older Indian or Greek sources. He revised Ptolemy's Geography and wrote on astronomy and astrology. However, scholars such as C.A. Nallino suggest that al-Khwarizmi's original work was not based on Ptolemy but on a derivative world map, presumably in Syriac or Arabic.

Spherical trigonometry

Further information: Law of sines and History of trigonometryThe spherical law of sines was discovered in the 10th century: it has been attributed variously to Abu-Mahmud Khojandi, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi and Abu Nasr Mansur, with Abu al-Wafa' Buzjani as a contributor. Ibn Muʿādh al-Jayyānī's The book of unknown arcs of a sphere in the 11th century introduced the general law of sines. The plane law of sines was described in the 13th century by Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī. In his On the Sector Figure, he stated the law of sines for plane and spherical triangles, and provided proofs for this law.

Other major figures

- 'Abd al-Hamīd ibn Turk (fl. 830) (quadratics)

- Thabit ibn Qurra (826–901)

- Sind ibn Ali (d. after 864)

- Ismail al-Jazari (1136–1206)

- Abū Sahl al-Qūhī (c. 940–1000) (centers of gravity)

- Abu'l-Hasan al-Uqlidisi (952–953) (arithmetic)

- 'Abd al-'Aziz al-Qabisi (d. 967)

- Ibn al-Haytham (ca. 965–1040)

- Abū al-Rayḥān al-Bīrūnī (973–1048) (trigonometry)

- Ibn Maḍāʾ (c. 1116–1196)

- Jamshīd al-Kāshī (c. 1380–1429) (decimals and estimation of the circle constant)

Gallery

-

Engraving of Abū Sahl al-Qūhī's perfect compass to draw conic sections.

Engraving of Abū Sahl al-Qūhī's perfect compass to draw conic sections.

-

The theorem of Ibn Haytham.

See also

- Arabic numerals

- Indian influence on Islamic mathematics in medieval Islam

- History of calculus

- History of geometry

- Science in the medieval Islamic world

- Timeline of Islamic science and technology

References

- Katz (1993): "A complete history of mathematics of medieval Islam cannot yet be written, since so many of these Arabic manuscripts lie unstudied... Still, the general outline... is known. In particular, Islamic mathematicians fully developed the decimal place-value number system to include decimal fractions, systematised the study of algebra and began to consider the relationship between algebra and geometry, studied and made advances on the major Greek geometrical treatises of Euclid, Archimedes, and Apollonius, and made significant improvements in plane and spherical geometry." Smith (1958) Vol. 1, Chapter VII.4: "In a general way it may be said that the Golden Age of Arabian mathematics was confined largely to the 9th and 10th centuries; that the world owes a great debt to Arab scholars for preserving and transmitting to posterity the classics of Greek mathematics; and that their work was chiefly that of transmission, although they developed considerable originality in algebra and showed some genius in their work in trigonometry."

- Adolph P. Yushkevich Sertima, Ivan Van (1992), Golden age of the Moor, Volume 11, Transaction Publishers, p. 394, ISBN 1-56000-581-5 "The Islamic mathematicians exercised a prolific influence on the development of science in Europe, enriched as much by their own discoveries as those they had inherited by the Indians, Greeks, the Syrians, the Babylonians, etc."

- "algebra". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Boyer, Carl B. (1991). "The Arabic Hegemony". A History of Mathematics (Second ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 228. ISBN 0-471-54397-7.

- Swetz, Frank J. (1993). Learning Activities from the History of Mathematics. Walch Publishing. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-8251-2264-4.

- ^ Gullberg, Jan (1997). Mathematics: From the Birth of Numbers. W. W. Norton. p. 298. ISBN 0-393-04002-X.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "al-Marrakushi ibn Al-Banna", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (1999), "Arabic mathematics: forgotten brilliance?", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Struik 1987, p. 96.

- ^ Boyer 1991, pp. 241–242. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBoyer1991 (help)

- ^ Struik 1987, p. 97.

- Berggren, J. Lennart; Al-Tūsī, Sharaf Al-Dīn; Rashed, Roshdi (1990). "Innovation and Tradition in Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī's al-Muʿādalāt". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 110 (2): 304–309. doi:10.2307/604533. JSTOR 604533.

- Bag, A.K. (1990). "Ritual Geometry in India and Parellelism in Other Cultural Areas". Indian Journal of History of Science. 25 (1–4).

- ^ Sesiano, Jacques (2000). Helaine, Selin; Ubiratan, D'Ambrosio (eds.). Islamic mathematics. Springer. pp. 137–157. ISBN 1-4020-0260-2.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Abu Mansur ibn Tahir Al-Baghdadi", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Allen, G. Donald (n.d.). "The History of Infinity" (PDF). Texas A&M University. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- Struik 1987, p. 93

- Rosen 1831, p. v–vi; Toomer 1990

- Nallino (1939).

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Abu Abd Allah Muhammad ibn Muadh Al-Jayyani", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Berggren, J. Lennart (2007). "Mathematics in Medieval Islam". The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook. Princeton University Press. p. 518. ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9.

Sources

- Boyer, Carl B. (1991), "Greek Trigonometry and Mensuration, and The Arabic Hegemony", A History of Mathematics (2nd ed.), New York City: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-54397-7

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nallino, C.A. (1939), "Al-Ḥuwārismī e il suo rifacimento della Geografia di Tolomeo", Raccolta di scritti editi e inediti, vol. V, Rome: Istituto per l'Oriente, pp. 458–532. Template:It icon

- Struik, Dirk J. (1987), A Concise History of Mathematics (4th rev. ed.), Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-60255-9

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Books on Islamic mathematics

- Berggren, J. Lennart (1986). Episodes in the Mathematics of Medieval Islam. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-96318-9.

- Review: Toomer, Gerald J.; Berggren, J. L. (1988). "Episodes in the Mathematics of Medieval Islam". American Mathematical Monthly. 95 (6). Mathematical Association of America: 567. doi:10.2307/2322777. JSTOR 2322777.

- Review: Hogendijk, Jan P.; Berggren, J. L. (1989). "Episodes in the Mathematics of Medieval Islam by J. Lennart Berggren". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 109 (4). American Oriental Society: 697–698. doi:10.2307/604119. JSTOR 604119.

- Daffa', Ali Abdullah al- (1977). The Muslim contribution to mathematics. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 0-85664-464-1.

- Katz, Victor J. (1993). A History of Mathematics: An Introduction. HarperCollins college publishers. ISBN 0-673-38039-4.

- Ronan, Colin A. (1983). The Cambridge Illustrated History of the World's Science. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-25844-8.

- Smith, David E. (1958). History of Mathematics. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-20429-4.

- Rashed, Roshdi (2001). The Development of Arabic Mathematics: Between Arithmetic and Algebra. Translated by A. F. W. Armstrong. Springer. ISBN 0-7923-2565-6.

- Rosen, Fredrick (1831). The Algebra of Mohammed Ben Musa. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1-4179-4914-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Toomer, Gerald (1990). "Al-Khwārizmī, Abu Ja'far Muḥammad ibn Mūsā". In Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.). Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. 7. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0-684-16962-2.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Youschkevitch, Adolf P.; Rozenfeld, Boris A. (1960). Die Mathematik der Länder des Ostens im Mittelalter. Berlin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) Sowjetische Beiträge zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaft pp. 62–160. - Youschkevitch, Adolf P. (1976). Les mathématiques arabes: VIII–XV siècles. translated by M. Cazenave and K. Jaouiche. Paris: Vrin. ISBN 978-2-7116-0734-1.

- Book chapters on Islamic mathematics

- Berggren, J. Lennart (2007). "Mathematics in Medieval Islam". In Victor J. Katz (ed.). The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook (Second ed.). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University. ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9.

- Cooke, Roger (1997). "Islamic Mathematics". The History of Mathematics: A Brief Course. Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 0-471-18082-3.

- Books on Islamic science

- Daffa, Ali Abdullah al-; Stroyls, J.J. (1984). Studies in the exact sciences in medieval Islam. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-90320-5.

- Kennedy, E. S. (1984). Studies in the Islamic Exact Sciences. Syracuse Univ Press. ISBN 0-8156-6067-7.

- Books on the history of mathematics

- Joseph, George Gheverghese (2000). The Crest of the Peacock: Non-European Roots of Mathematics (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00659-8. (Reviewed: Katz, Victor J.; Joseph, George Gheverghese (1992). "The Crest of the Peacock: Non-European Roots of Mathematics by George Gheverghese Joseph". The College Mathematics Journal. 23 (1). Mathematical Association of America: 82–84. doi:10.2307/2686206. JSTOR 2686206.)

- Youschkevitch, Adolf P. (1964). Gesichte der Mathematik im Mittelalter. Leipzig: BG Teubner Verlagsgesellschaft.

- Journal articles on Islamic mathematics

- Høyrup, Jens. “The Formation of «Islamic Mathematics»: Sources and Conditions”. Filosofi og Videnskabsteori på Roskilde Universitetscenter. 3. Række: Preprints og Reprints 1987 Nr. 1.

- Bibliographies and biographies

- Brockelmann, Carl. Geschichte der Arabischen Litteratur. 1.–2. Band, 1.–3. Supplementband. Berlin: Emil Fischer, 1898, 1902; Leiden: Brill, 1937, 1938, 1942.

- Sánchez Pérez, José A. (1921). Biografías de Matemáticos Árabes que florecieron en España. Madrid: Estanislao Maestre.

- Sezgin, Fuat (1997). Geschichte Des Arabischen Schrifttums (in German). Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-02007-1.

- Suter, Heinrich (1900). Die Mathematiker und Astronomen der Araber und ihre Werke. Abhandlungen zur Geschichte der Mathematischen Wissenschaften Mit Einschluss Ihrer Anwendungen, X Heft. Leipzig.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Television documentaries

- Marcus du Sautoy (presenter) (2008). "The Genius of the East". The Story of Maths. BBC.

- Jim Al-Khalili (presenter) (2010). Science and Islam. BBC.

External links

- Hogendijk, Jan P. (January 1999). "Bibliography of Mathematics in Medieval Islamic Civilization".

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (1999), "Arabic mathematics: forgotten brilliance?", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Richard Covington, Rediscovering Arabic Science, 2007, Saudi Aramco World

| Mathematics in the medieval Islamic world | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mathematicians |

|  | ||||||||||||||||

| Mathematical works | ||||||||||||||||||

| Concepts | ||||||||||||||||||

| Centers | ||||||||||||||||||

| Influences | ||||||||||||||||||

| Influenced | ||||||||||||||||||

| Related | ||||||||||||||||||

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).

, with a and b positive, he would note that the maximum point of the curve

, with a and b positive, he would note that the maximum point of the curve  occurs at

occurs at  , and that the equation would have no solutions, one solution or two solutions, depending on whether the height of the curve at that point was less than, equal to, or greater than a. His surviving works give no indication of how he discovered his formulae for the maxima of these curves. Various conjectures have been proposed to account for his discovery of them.

, and that the equation would have no solutions, one solution or two solutions, depending on whether the height of the curve at that point was less than, equal to, or greater than a. His surviving works give no indication of how he discovered his formulae for the maxima of these curves. Various conjectures have been proposed to account for his discovery of them.