| Revision as of 21:37, 16 September 2017 editAnomieBOT (talk | contribs)Bots6,567,031 edits Rescuing orphaned refs ("imdb.com" from rev 800664116)← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:27, 23 September 2017 edit undo74.89.179.18 (talk) →Death: Added contentTags: canned edit summary Mobile edit Mobile web editNext edit → | ||

| Line 155: | Line 155: | ||

| == Death == | == Death == | ||

| ] covered with flowers, beer bottles, fan letters, etc.]] | ] covered with flowers, beer bottles, fan letters, etc.]] | ||

| On December 10, 2005, Pryor suffered a heart attack in Los Angeles. He was taken to a local hospital after his wife's attempts to resuscitate him failed. He was pronounced dead at 7:58 am ]. He was 65 years old. His widow Jennifer was quoted as saying, "At the end, there was a smile on his face."<ref name="BBCobit" /> He was ], and his ashes were given to his family.{{citation needed|date=January 2015}} Forensic pathologist Dr. Michael Hunter believes Pryor's fatal heart attack was caused by ] that was at least partially brought about by years of tobacco smoking.<ref>"Autopsy: The Last Hours Of Richard Pryor." ''Autopsy''. Nar. Eric Meyers. Exec. Prod. Ed Taylor and Michael Kelpie. Reelz, March 25, 2017. Television.</ref> | On December 10, 2005, Pryor suffered a heart attack in Los Angeles. He was taken to a local hospital after his wife's attempts to resuscitate him failed. He was pronounced dead at 7:58 am ]. He was 65 years old. His widow Jennifer was quoted as saying, "At the end, there was a smile on his face."<ref name="BBCobit" /> He was ], and his ashes were given to his family.{{citation needed|date=January 2015}} Forensic pathologist Dr. Michael Hunter believes Pryor's fatal heart attack was caused by ] that was at least partially brought about by years of tobacco smoking, drinking, and drug use.<ref>"Autopsy: The Last Hours Of Richard Pryor." ''Autopsy''. Nar. Eric Meyers. Exec. Prod. Ed Taylor and Michael Kelpie. Reelz, March 25, 2017. Television.</ref> | ||

| == Remembrance and legacy == | == Remembrance and legacy == | ||

Revision as of 20:27, 23 September 2017

For American broadcaster and humorist, see Cactus Pryor.

| Richard Pryor | |

|---|---|

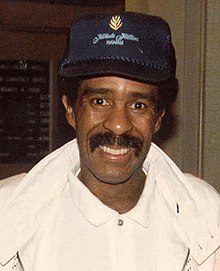

Pryor in February 1986 Pryor in February 1986 | |

| Birth name | Richard Franklin Lennox Thomas Pryor |

| Born | (1940-12-01)December 1, 1940 Peoria, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | December 10, 2005(2005-12-10) (aged 65) Encino, Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Medium | Stand-up, film, television |

| Nationality | American |

| Years active | 1963–2005 |

| Genres | Political satire, observational comedy, black comedy, improvisational comedy, character comedy |

| Subject(s) | Racism, race relations, American politics, African-American culture, human sexuality, religion, self-deprecation, everyday life, recreational drug use |

| Spouse |

|

| Children | 7 |

| Notable works and roles | Himself in Richard Pryor: Live in Concert and Richard Pryor: Live on the Sunset Strip Daddy Rich in Car Wash Wally Karue in See No Evil, Hear No Evil Harry Monroe in Stir Crazy Gus Gorman in Superman III Monty Brewster in Brewster's Millions |

| Website | RichardPryor.com |

Richard Franklin Lennox Thomas Pryor (December 1, 1940 – December 10, 2005) was an American comedian, actor, and social critic. Pryor was known for uncompromising examinations of racism and topical contemporary issues, which employed colorful vulgarities and profanity, as well as racial epithets. He reached a broad audience with his trenchant observations and storytelling style. He is widely regarded as one of the most important and influential stand-up comedians of all time: Jerry Seinfeld called Pryor "The Picasso of our profession" and Bob Newhart heralded Pryor as "the seminal comedian of the last 50 years". Dave Chappelle said of Pryor, "You know those, like, evolution charts of man? He was the dude walking upright. Richard was the highest evolution of comedy." This legacy can be attributed, in part, to the unusual degree of intimacy Pryor brought to bear on his comedy. As Bill Cosby reportedly once said, "Richard Pryor drew the line between comedy and tragedy as thin as one could possibly paint it."

Pryor's body of work includes the concert movies and recordings: Richard Pryor: Live & Smokin' (1971), That Nigger's Crazy (1974), ...Is It Something I Said? (1975), Bicentennial Nigger (1976), Richard Pryor: Live in Concert (1979), Richard Pryor: Live on the Sunset Strip (1982), and Richard Pryor: Here and Now (1983). As an actor, he starred mainly in comedies such as Silver Streak (1976), but occasionally in dramas, such as Paul Schrader's Blue Collar (1978), or action films, such as Superman III (1983). He collaborated on many projects with actor Gene Wilder. Another frequent collaborator was actor/comedian/writer Paul Mooney.

Pryor won an Emmy Award (1973) and five Grammy Awards (1974, 1975, 1976, 1981, and 1982). In 1974, he also won two American Academy of Humor awards and the Writers Guild of America Award. The first-ever Kennedy Center Mark Twain Prize for American Humor was presented to him in 1998. He was listed at number one on Comedy Central's list of all-time greatest stand-up comedians. In 2017, Rolling Stone ranked him first on its list of the 50 best stand-up comics of all time.

Early life

Born on December 1, 1940, in Peoria, Illinois, Richard Franklin Lennox Thomas Pryor grew up in his grandmother's brothel, where his mother, Gertrude L. (née Thomas), practiced prostitution. His father, LeRoy "Buck Carter" Pryor (June 7, 1915 – September 27, 1968), was a former boxer and hustler. After his alcoholic mother abandoned him when he was 10, Pryor was raised primarily by his grandmother Marie Carter, a tall, violent woman who would beat him for any of his eccentricities. Pryor was one of four children raised in his grandmother's brothel and was sexually abused at age seven. He was expelled from school at the age of 14.

His first professional performance was playing drums at a night club. Pryor served in the U.S. Army from 1958 to 1960, but spent virtually the entire stint in an army prison. According to a 1999 profile about Pryor in The New Yorker, Pryor was incarcerated for an incident that occurred while stationed in Germany. Angered that a white soldier was overly amused at the racially charged sections of Douglas Sirk's movie Imitation of Life (1959), Pryor and some other black soldiers beat and stabbed him, though not fatally.

Career

Early career (1963–1968)

In 1963, Pryor moved to New York City and began performing regularly in clubs alongside performers such as Bob Dylan and Woody Allen. On one of his first nights, he opened for singer and pianist Nina Simone at New York's Village Gate. Simone recalls Pryor's bout of performance anxiety:

He shook like he had malaria, he was so nervous. I couldn't bear to watch him shiver, so I put my arms around him there in the dark and rocked him like a baby until he calmed down. The next night was the same, and the next, and I rocked him each time.

Inspired by Bill Cosby, Pryor began as a middlebrow comic, with material far less controversial than what was to come. Soon, he began appearing regularly on television variety shows, such as The Ed Sullivan Show, The Merv Griffin Show, and The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. His popularity led to success as a comic in Las Vegas. The first five tracks on the 2005 compilation CD Evolution/Revolution: The Early Years (1966–1974), recorded in 1966 and 1967, capture Pryor in this period.

In September 1967, Pryor had what he described in his autobiography Pryor Convictions (1995) as an "epiphany". He walked onto the stage at the Aladdin Hotel in Las Vegas (with Dean Martin in the audience), looked at the sold-out crowd, exclaimed over the microphone, "What the fuck am I doing here!?", and walked off the stage. Afterward, Pryor began working profanity into his act, including the word "nigger". His first comedy recording, the eponymous 1968 debut release on the Dove/Reprise label, captures this particular period, tracking the evolution of Pryor's routine. Around this time, his parents died—his mother in 1967 and his father in 1968.

Mainstream success

1969–1983

In 1969, Pryor moved to Berkeley, California, where he immersed himself in the counterculture and rubbed elbows with the likes of Huey P. Newton and Ishmael Reed. He signed with the comedy-oriented independent record label Laff Records in 1970, and in 1971 recorded his second album, Craps (After Hours). Two years later, the relatively unknown comedian appeared in the documentary Wattstax (1972), wherein he riffed on the tragic-comic absurdities of race relations in Watts and the nation. Not long afterward, Pryor sought a deal with a larger label, and he signed with Stax Records in 1973.

When his third, breakthrough album, That Nigger's Crazy (1974), was released, Laff, which claimed ownership of Pryor's recording rights, almost succeeded in getting an injunction to prevent the album from being sold. Negotiations led to Pryor's release from his Laff contract. In return for this concession, Laff was enabled to release previously unissued material, recorded between 1968 and 1973, at will. That Nigger's Crazy was a commercial and critical success; it was eventually certified gold by the RIAA and won the Grammy Award for Best Comedic Recording at the 1975 Grammy Awards.

During the legal battle, Stax briefly closed its doors. At this time, Pryor returned to Reprise/Warner Bros. Records, which re-released That Nigger's Crazy, immediately after ...Is It Something I Said?, his first album with his new label. Like That Nigger's Crazy, the album was a hit with both critics and fans; it was eventually certified platinum by the RIAA and won the Grammy Award for Best Comedic Recording at the 1976 Grammy Awards.

Pryor's release Bicentennial Nigger (1976) continued his streak of success. It became his third consecutive gold album, and he collected his third consecutive Grammy for Best Comedic Recording for the album in 1977. With every successful album Pryor recorded for Warner (or later, his concert films and his 1980 freebasing accident), Laff quickly published an album of older material to capitalize on Pryor's growing fame—a practice they continued until 1983. The covers of Laff albums tied in thematically with Pryor movies, such as Are You Serious? for Silver Streak (1976), The Wizard of Comedy for his appearance in The Wiz (1978), and Insane for Stir Crazy (1980).

In the 1970s, Pryor wrote for such television shows as Sanford and Son, The Flip Wilson Show, and a 1973 Lily Tomlin special, for which he shared an Emmy Award. During this period, Pryor tried to break into mainstream television. He was a guest host on the first season of Saturday Night Live and the first black person to host the show. Pryor took longtime girlfriend, actress-talk show host Kathrine McKee (sister of Lonette McKee), with him to New York, and she made a brief guest appearance with Pryor on SNL. He participated in the "word association" skit with Chevy Chase.

In 1974, Pryor was arrested for income tax evasion and served 10 days in jail.

The Richard Pryor Show premiered on NBC in 1977, but was cancelled after only four episodes probably because television audiences did not respond well to his show's controversial subject matter, and Pryor was unwilling to alter his material for network censors. During the short-lived series, he portrayed the first black President of the United States, spoofed the Star Wars cantina, took on gun violence, and in another skit, used costumes and visual distortion to appear nude.

In 1979, at the height of his success, Pryor visited Africa. Upon returning to the United States, Pryor swore he would never use the word "nigger" in his stand-up comedy routine again. However, his favorite epithet, "motherfucker", remains a term of endearment on his official website.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Pryor appeared in several popular films, including Lady Sings the Blues (1972), The Mack (1973), Uptown Saturday Night (1974), Silver Streak (1976), Car Wash (1976), Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings (1976), Which Way Is Up? (1977), Greased Lightning (1977), Blue Collar (1978), The Muppet Movie (1979), Stir Crazy (1980), and Bustin' Loose (1981). Next, Pryor co-starred with Jackie Gleason in The Toy (1982).

Pryor co-wrote Blazing Saddles (1974), directed by Mel Brooks and starring Gene Wilder. Pryor was to play the lead role of Bart, but the film's production studio would not insure him, and Mel Brooks chose Cleavon Little, instead. Before his horribly damaging 1980 freebasing incident, Pryor was about to start filming Mel Brooks' History of the World, Part I (1981), but was replaced at the last minute by Gregory Hines. Pryor was also originally considered for the role of Billy Ray Valentine on Trading Places (1983), before Eddie Murphy won the part.

1980–1990

In 1983, Pryor signed a five-year contract with Columbia Pictures for US$40 million and he started his own production company, Indigo Productions. Softer, more formulaic films followed, including Superman III (1983), which earned Pryor $4 million; Brewster's Millions (1985), Moving (1988), and See No Evil, Hear No Evil (1989). The only film project from this period that recalled his rough roots was Pryor's semiautobiographic debut as a writer-director, Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life Is Calling (1986), which was not a major success.

Despite a reputation for constantly using profanity on and off camera, Pryor briefly hosted a children's show on CBS called Pryor's Place (1984). Like Sesame Street, Pryor's Place featured a cast of puppets, hanging out and having fun in a surprisingly friendly inner-city environment along with several children and characters portrayed by Pryor himself. However, Pryor's Place frequently dealt with more sobering issues than Sesame Street. It was cancelled shortly after its debut, despite the efforts of famed puppeteers Sid and Marty Krofft and a theme song by Ray Parker, Jr. of "Ghostbusters" (1984) fame.

Pryor co-hosted the Academy Awards twice and was nominated for an Emmy for a guest role on the television series Chicago Hope. Network censors had warned Pryor about his profanity for the Academy Awards, and after a slip early in the program, a five-second delay was instituted when returning from a commercial break. Pryor is also one of only three Saturday Night Live hosts to be subjected to a rare five-second delay for his 1975 appearance (along with Sam Kinison in 1986 and Andrew Dice Clay in 1990).

Pryor developed a reputation for being demanding and disrespectful on film sets, and for making selfish and difficult requests. In his autobiography Kiss Me Like a Stranger, co-star Gene Wilder says that Pryor was frequently late to the set during filming of Stir Crazy, and that he demanded, among other things, a helicopter to fly him to and from set because he was the star. Pryor was also accused of using allegations of on-set racism to force the hand of film producers into giving him more money. Also from Wilder's book:

One day during our lunch hour in the last week of filming, the craft service man handed out slices of watermelon to each of us. Richard, the whole camera crew, and I sat together in a big sound studio eating a number of watermelon slices, talking and joking. As a gag, some members of the crew used a piece of watermelon as a Frisbee, and tossed it back and forth to each other. One piece of watermelon landed at Richard's feet. He got up and went home. Filming stopped. The next day, Richard announced that he knew very well what the significance of watermelon was. He said that he was quitting show business and would not return to this film. The day after that, Richard walked in, all smiles. I wasn't privy to all the negotiations that went on between Columbia and Richard's lawyers, but the camera operator who had thrown that errant piece of watermelon had been fired that day. I assume now that Richard was using drugs during Stir Crazy.

He appeared in Harlem Nights (1989), a comedy-drama crime film starring three generations of black comedians (Pryor, Eddie Murphy, and Redd Foxx).

Personal life and health

Pryor was a Freemason in a lodge in Peoria, Illinois.

In November 1977, after many years of heavy smoking and drinking, Pryor suffered a mild heart attack. He recovered and resumed performing by January the following year. He was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 1986. In 1990, Pryor suffered a second heart attack while in Australia. He underwent triple heart bypass surgery in 1991.

Freebase cocaine incident

On the late evening of June 9, 1980, during the making of the film Stir Crazy, after days of freebasing cocaine, Pryor poured 151-proof rum all over himself and lit himself on fire. While ablaze, he ran down Parthenia Street from his Los Angeles home, until being subdued by police. He was taken to a hospital, where he was treated for second- and third-degree burns covering more than half of his body. Pryor spent six weeks in recovery at the Grossman Burn Center at Sherman Oaks Hospital. His daughter, Rain, stated that the incident happened as a result of a bout of drug-induced psychosis.

Pryor incorporated a description of the incident into his comedy show Richard Pryor: Live on the Sunset Strip (1982). He joked that the event was caused by dunking a cookie into a glass of low-fat and pasteurized milk, causing an explosion. At the end of the bit, he poked fun at people who told jokes about it by waving a lit match and saying, "What's that? Richard Pryor running down the street."

After his "final performance", Pryor did not stay away from stand-up comedy long. Within a year, he filmed and released a new concert film and accompanying album, Richard Pryor: Here and Now (1983), which he directed himself. He also wrote and directed a fictionalized account of his life, Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life Is Calling (1986), which revolved around the 1980 freebasing incident.

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (June 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Marriages and relationships

Pryor was married seven times to five women. His wives were:

- Patricia Price, whom he married in 1960 and divorced the following year. From this marriage, a son, Richard Pryor Jr. (1961), was born.

- Shelley Bonus, whom he married in 1967 and divorced in 1969.

- Deborah McGuire, whom he married on September 22, 1977; they divorced the following year.

- Jennifer Lee, whom he married in August 1981. They divorced in October 1982, but later remarried on June 29, 2001, and remained married until Pryor's death.

- Flynn Belaine, whom he married in October 1986. They were divorced in July 1987, but later remarried on April 1, 1990. They divorced again in July 1991.

Children

- Renee Pryor, born in 1957, the child of Pryor and girlfriend Susan, when Pryor was 17.

- Richard Pryor, Jr., born in 1961, the child of Pryor and his first wife, Patricia Price.

- Elizabeth Ann, born in April 1967, the child of Pryor and girlfriend Maxine Anderson (aka Maxine Silverman).

- Rain Pryor, born July 16, 1969, the child of Pryor and his second wife, Shelley Bonus.

- Steven, born in 1984, the child of Pryor and Flynn Belaine, who later became his fifth wife.

- Kelsey, born in October 1987, the child of Pryor and his fifth wife, Flynn Belaine.

- Franklin, born in 1987, the child of Pryor and actress/model Geraldine Mason.

Pryor also had relationships with actresses Pam Grier and Margot Kidder.

Later life (1990–2005)

In his later years starting in the early to mid-1990s, Pryor used a power-operated mobility scooter due to multiple sclerosis (MS, which he said stood for "More Shit"). He appears on the scooter in his last film appearance, a small role in David Lynch's Lost Highway (1997) playing an auto-repair garage manager named Arnie.

In 1998, Pryor won the first Mark Twain Prize for American Humor from the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. According to former Kennedy Center President Lawrence J. Wilker, Pryor was selected as the first recipient of the Prize because

as a stand-up comic, writer, and actor, he struck a chord, and a nerve, with America, forcing it to look at large social questions of race and the more tragicomic aspects of the human condition. Though uncompromising in his wit, Pryor, like Twain, projects a generosity of spirit that unites us. They were both trenchant social critics who spoke the truth, however outrageous.

Rhino Records remastered all of Pryor's Reprise and WB albums for inclusion in the box set ...And It's Deep Too! The Complete Warner Bros. Recordings (2000).

In early 2000, Pryor appeared in the cold open of The Norm Show in the episode entitled "Norm vs. The Boxer". He played an elderly man in a wheelchair who lost the rights to in-home nursing when he kept attacking the nurses before attacking Norm himself.

In 2001, he remarried Jennifer Lee, who had also become his manager.

In 2002, a television documentary entitled The Funny Life of Richard Pryor depicted Pryor's life and career. Broadcast in the UK as part of the Channel 4 series Kings of Black Comedy, it was produced, directed and narrated by David Upshal and featured rare clips from Pryor's 1960s stand-up appearances and movies such as Silver Streak (1976), Blue Collar (1978), Richard Pryor: Live in Concert (1978), and Stir Crazy (1980). Contributors included George Carlin, Dave Chappelle, Whoopi Goldberg, Ice-T, Paul Mooney, Joan Rivers, and Lily Tomlin. The show tracked down the two cops who had rescued Pryor from his "freebasing incident", former managers, and even school friends from Pryor's home town of Peoria, Illinois. In the US, the show went out as part of the Heroes of Black Comedy series on Comedy Central, narrated by Don Cheadle.

In 2002, Pryor and his wife/manager, Jennifer Lee Pryor, won legal rights to all the Laff material, which amounted to almost 40 hours of reel-to-reel analog tape. After going through the tapes and getting Richard's blessing, Jennifer Lee Pryor gave Rhino Records access to the tapes in 2004. These tapes, including the entire Craps album, form the basis of the February 1, 2005, double-CD release Evolution/Revolution: The Early Years (1966–1974).

A television documentary, Richard Pryor: I Ain't Dead Yet, #*%$#@!! (2003) consisted of archival footage of Pryor's performances and testimonials from fellow comedians, including Dave Chappelle, Denis Leary, Chris Rock, and Wanda Sykes, on Pryor's influence on comedy.

In 2004, Pryor was voted number one on Comedy Central's list of the 100 Greatest Stand-ups of All Time.

In late 2004, his sister said he had lost his voice as result of his multiple sclerosis. However, on January 9, 2005, Pryor's wife, Jennifer Lee, rebutted this statement in a post on Pryor's official website, citing Richard as saying: "I'm sick of hearing this shit about me not talking... not true... I have good days, bad days... but I still am a talkin' motherfucker!"

In a 2005 British poll to find "The Comedian's Comedian", Pryor was voted the 10th-greatest comedy act ever by fellow comedians and comedy insiders.

Death

On December 10, 2005, Pryor suffered a heart attack in Los Angeles. He was taken to a local hospital after his wife's attempts to resuscitate him failed. He was pronounced dead at 7:58 am PST. He was 65 years old. His widow Jennifer was quoted as saying, "At the end, there was a smile on his face." He was cremated, and his ashes were given to his family. Forensic pathologist Dr. Michael Hunter believes Pryor's fatal heart attack was caused by coronary artery disease that was at least partially brought about by years of tobacco smoking, drinking, and drug use.

Remembrance and legacy

A retrospective of Pryor's film work, concentrating on the 1970s, titled A Pryor Engagement, opened at Brooklyn Academy of Music Cinemas for a two-week run in February 2013. Prolific comedians who have claimed Pryor as an influence include George Carlin, Dave Attell, Martin Lawrence, Dave Chappelle, Chris Rock, Colin Quinn, Patrice O'Neal, Bill Hicks, Sam Kinison, Bill Burr, Louis C.K., Jerry Seinfeld, Jon Stewart, Eddie Murphy, Eddie Griffin, and Eddie Izzard.

In films and television

In 2002, Channel 4 in the UK broadcast The Funny Life of Richard Pryor, a one-hour biographical documentary directed by David Upshal, as part of the series Kings of Black Comedy. In the US, the documentary was broadcast on Comedy Central as part of the Heroes of Black Comedy series.

On December 14, 2005, the episode "George Is Being Elfish and Christ-misses His Family" of the comedian hit show George Lopez was dedicated to Pryor in his memory.

On December 19, 2005, BET aired a Pryor special. It included commentary from fellow comedians, and insight into his upbringing.

On March 1, 2008, fellow comedian George Carlin performed his final HBO special. An image of Pryor can be seen in the background throughout his set. Carlin would mention Pryor's death in his memoir, Last Words (2009), noting their friendly rivalry that lasted until Carlin finally beat him "in the Heart Attack 5000".

In the episode "Taxes and Death or Get Him to the Sunset Strip"(2012), the voice of Richard Pryor is played by Eddie Griffin in the satirical TV show Black Dynamite.

On May 31, 2013, Showtime debuted the documentary Richard Pryor: Omit the Logic directed by Emmy Award–winning filmmaker Marina Zenovich. The executive producers are Pryor's widow Jennifer Lee Pryor and Roy Ackerman. Interviewees include Dave Chappelle, Whoopi Goldberg, Jesse Jackson, Quincy Jones, George Lopez, Bob Newhart, Richard Pryor, Jr., Lily Tomlin, and Robin Williams.

Biopic

A planned biopic, entitled Richard Pryor: Is It Something I Said?, was being produced by Chris Rock and Adam Sandler. The film would have starred Marlon Wayans as the young Pryor. Other actors previously attached include Mike Epps and Eddie Murph]. The film would have been directed by Bill Condon and was still in development with no release date, as of February 2013.

The biopic remained in limbo, and went through several producers until it was announced in January 2014 that it was being backed by The Weinstein Company with Lee Daniels as director. It was further announced, in August 2014, that the biopic will have Oprah Winfrey as producer and will star Mike Epps as Pryor.

Literature

- Rovin, Jeff. Richard Pryor: Black and Blue. London: Orbis, 1983.

- Haskins, James. Richard Pryor, A Man and His Madness: A Biography. New York: Beaufort Books, 1984.

- Williams, John A. and Dennis A. Williams. If I Stop I'll Die: The Comedy and Tragedy of Richard Pryor. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press, 1991.

- Pryor, Richard with Todd Gold. Pryor Convictions and Other Life Sentences. New York: Pantheon Books, 1995.

- Pryor, Rain with Cathy Crimmins. Jokes My Father Never Taught Me: Life, Love, and Loss with Richard Pryor. New York: HarperCollins, 2006.

- McCluskey, Audrey Thomas, ed. Richard Pryor: The Life and Legacy of a "Crazy" Black Man. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2008.

- Brown, Cecil. Pryor Lives! How Richard Pryor Became Richard Pryor. CreateSpace, 2013.

- Henry, David and Joe Henry. Furious Cool: Richard Pryor and the World That Made Him. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books, 2013.

- Saul, Scott. Becoming Richard Pryor. New York: HarperCollins, 2014.

- Bailey, Jason. Richard Pryor: American Id. Raleigh, NC: The Critical Press, 2015.

In radio

From June 7 to 9, 2013, SiriusXM hosted "Richard Pryor Radio", a three-day tribute which featured his stand-up comedy and full live concerts. "Richard Pryor Radio" replaced The Foxxhole for the duration of the event.

Posthumous awards

Pryor was posthumously awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2006.

Awards in Pryor's name

The animal rights organization PETA gives out an award in Pryor's name to people who have done outstanding work to alleviate animal suffering. Pryor was active in animal rights and was deeply concerned about the plight of elephants in circuses and zoos.

Hometown statue

Artist Preston Jackson created a life-sized bronze statue in dedication to the beloved comedian and named it "Richard Pryor: More than Just a Comedian". It was placed at the corner of State and Washington Streets in downtown Peoria, on May 1, 2015, close to the neighborhood in which he grew up with his mother. The unveiling was held Sunday, May 3, 2015.

Discography

Albums

- 1968: Richard Pryor (Dove/Reprise)

- 1971: Craps (Laff Records, reissued 1993 by Loose Cannon/Island)

- 1974: That Nigger's Crazy (Partee/Stax, reissued 1975 by Reprise)

- 1975: ...Is It Something I Said? (Reprise, reissued 1991 on CD by Warner Archives)

- 1976: Holy Smoke! (Laff)

- 1976: Bicentennial Nigger (Reprise)

- 1976: L.A. Jail (Tiger Lily)

- 1977: Are You Serious ??? (Laff)

- 1977: Who Me? I'm Not Him (Laff)

- 1978: Black Ben The Blacksmith (Laff)

- 1978: The Wizard of Comedy (Laff)

- 1978: Wanted: Live in Concert (2-LP set) (Warner Bros. Records);Others

- 1979: Outrageous (Laff)

- 1980: Insane (Laff)

- 1981: Rev. Du Rite (Laff)

- 1982: Richard Pryor Live! (picture disc) (Phoenix/Audiofidelity)

- 1982: Richard Pryor: Live on the Sunset Strip (Warner Bros. Records)

- 1983: Here and Now (Warner Bros. Records)

- 1983: Supernigger (Laff)

Compilations

- 1973: Pryor Goes Foxx Hunting (Laff.)

- Split LP with Redd Foxx, containing previously released tracks from Craps (After Hours)

- 1975: Down And Dirty (Laff.)

- Split LP with Redd Foxx, containing previously released tracks from Craps (After Hours)

- 1976: Richard Pryor Meets... Richard & Willie And... The SLA!! (Laff)

- Split LP with black ventriloquist act Richard And Willie, containing previously released tracks from Craps (After Hours)

- 1977: Richard Pryor's Greatest Hits (Warner Bros. Records)

- Contains tracks from Craps (After Hours), That Nigger's Crazy, and ...Is It Something I Said?, plus a previously unreleased track from 1975, "Ali".1982 The Very Best of Richard Pryor"

- 2000: ...And It's Deep Too! The Complete Warner Bros. Recordings (9-CD box set) (Warner Bros. Records/Rhino)

- Box set collection containing all Warner Bros. albums plus a bonus disc of previously unissued material from 1973 to 1992.

- 2002: The Anthology (2-CD set) (Warner Bros. Records/Rhino, 2002 in music)

- Highlights culled from the albums collected in the ...And It's Deep Too! box set.

- 2005: Evolution/Revolution: The Early Years (1966–1974) (2-CD set) (Warner Bros. Records/Rhino, 2005 in music)

- Pryor-authorized compilation of material released on Laff, including the entire Craps (After Hours) album.

- 2013: No Pryor Restraint: Life In Concert (7-CD, 2-DVD box set) (Shout! Factory)

- Box set containing concert films, albums and unreleased material from 1966 to 1992.

Filmography

- 1967: The Busy Body as Whittaker

- 1968: Wild in the Streets as Stanley X

- 1969: Uncle Tom's Fairy Tales

- 1970: Carter's Army as Pvt. Jonathan Crunk

- 1970: The Phynx as himself

- 1971: You've Got to Walk It Like You Talk It or You'll Lose That Beat as Wino

- 1971: Live & Smokin' as himself

- 1971: Dynamite Chicken as himself

- 1972: Lady Sings the Blues as Piano Man

- 1973: The Mack as Slim

- 1973: Some Call It Loving as Jeff

- 1973: Hit! as Mike Willmer

- 1973: Wattstax as himself

- 1974: Uptown Saturday Night as Sharp Eye Washington

- 1975: The Lion Roars Again as himself

- 1976: Adiós Amigo as Sam Spade

- 1976: The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings as Charlie Snow, All-Star (RF)

- 1976: Car Wash as Daddy Rich

- 1976: Silver Streak as Grover

- 1977: Greased Lightning as Wendell Scott

- 1977: Which Way Is Up? as Leroy Jones / Rufus Jones / Reverend Lenox Thomas

- 1978: Blue Collar as Zeke

- 1978: The Wiz as The Wiz (Herman Smith)

- 1978: California Suite as Dr. Chauncey Gump

- 1979: Richard Pryor: Live in Concert as himself

- 1979: The Muppet Movie as Balloon Vendor (cameo)

- 1980: Wholly Moses as Pharaoh

- 1980: In God We Tru$t as G.O.D.

- 1980: Stir Crazy as Harry Monroe

- 1981: Bustin' Loose as Joe Braxton

- 1982: Some Kind of Hero as Eddie Keller

- 1982: Richard Pryor: Live on the Sunset Strip as himself

- 1982: The Toy as Jack Brown

- 1983: Superman III as Gus Gorman

- 1983: Richard Pryor: Here and Now as himself

- 1983: Motown 25 as himself

- 1985: Brewster's Millions as Montgomery Brewster

- 1986: Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life Is Calling as Jo Jo Dancer / Alter Ego

- 1987: Critical Condition as Kevin Lenahan / Dr. Eddie Slattery

- 1988: Moving as Arlo Pear

- 1989: See No Evil, Hear No Evil as Wallace 'Wally' Karue

- 1989: Harlem Nights as Sugar Ray

- 1991: Another You as Eddie Dash

- 1991: The Three Muscatels as Narrator / Wino / Bartender

- 1994: A Century of Cinema as himself

- 1996: Mad Dog Time as Jimmy the Grave Digger

- 1996: Malcolm & Eddie (Season 1, episode, Do the K.C. Hustle) as Uncle Bucky

- 1997: Lost Highway as Arnie

- 1999: The Norm Show (cameo in opening of season 2, episode 11) as Mr. Johnson

- 2000: Me Myself and Irene as Stand-Up Comedian on TV (uncredited)

- 2003: Bitter Jester as himself

- 2003: I Ain't Dead Yet, #* %$@!! (archive footage)

- 2005: Richard Pryor: The Funniest Man Dead Or Alive (archive footage)

- 2009: Black Dynamite (archive footage)

- 2013: Richard Pryor: Omit the Logic as Himself (archive footage)

References

- Staff writer (May 21, 2004). "Pryor: I Owe It All to Lenny Bruce". Contactmusic.com. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- "George Carlin". Inside the Actors Studio. Season 1. Episode 4. October 31, 2004. Bravo.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|episodelink=ignored (|episode-link=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help) - Allis, Tim (April 12, 1993). "Court Jester". People. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- Lopez, George; Keteyian, Armen (2004). Why You Crying?: My Long, Hard Look at Life, Love, and Laughter. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-5994-7.

- Margaret Cho. "Richard Pryor". Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved December 4, 2003.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Dave Chappelle". Inside the Actors Studio. Season 12. Episode 10. February 12, 2006. Bravo.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|episodelink=ignored (|episode-link=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Reid aheem (December 12, 2005). "Chris Rock, Bernie Mac, Eddie Murphy Call Pryor The Real King Of Comedy — 'Without Richard, There Would Be No Me,' Bernie Mac Says". MTV. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ^ Richard Pryor: I Ain't Dead Yet, #*%$@!!, 2003, Comedy Central

- Fade to Black – Interviews – Bill Hicks Archived February 5, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- Gillette, Amelie (June 7, 2006). "Lewis Black". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on December 31, 2008. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Colin Quinn". Popentertainment.com. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- "Chris Tucker – Movie and Film Biography and Filmography – AllRovi.com". AllMovie.

- "Interview with Louis C.K." One Night Stand. HBO. 2005. Retrieved December 6, 2007.

- "aspecialthing.com :: View topic – THE AST INTERVIEW: PATTON OSWALT". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved September 24, 2010.

- Kirschling, Gregory (November 7, 2008). "Artie Lange: 'F--- It, I'll Write a Book'". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved November 11, 2008.

- Gillick, Jeremy; Gorilovskaya, Nonna (November–December 2008). "Meet Jonathan Stuart Leibowitz (aka) Jon Stewart: The wildly zeitgeisty Daily Show host". Moment. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved August 10, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Interview with Bill Zehme, Richard Lewis: Concerts from Hell: The Vintage Years, Image Entertainment, Released September 13, 2005

- "Interview with Jim Norton". One Night Stand. HBO. 2005. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- "John Oliver Reveals His 5 Comedic Influences". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 31, 2015. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Morton, Bruce (December 21, 2005). "Those We Lost". CNN. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- "Bob Newhart". PBS American Masters.

- "Dave Chappelle". Inside the Actors Studio. Season 12. Episode 10. February 12, 2006. Bravo.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|episodelink=ignored (|episode-link=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help) - O'Benson, Tambay. "Richard Pryor Retrospective at BAMcinématek, Brooklyn (10 Days, 20 Films, All in 35 mm)". Indiewire. Retrieved December 26, 2012.

- ^ "Why Chappelle is the man". Vox Magazine. September 30, 2004. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

Pryor was voted No. 1 in Comedy Central's 100 Greatest Stand-Ups of All Time in April.

- The 50 Best Stand-up Comics of All Time. Rollingstone.com, retrieved February 15, 2017.

- "Richard the Great". New York Post. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- "Richard Pryor's official biography". RichardPryor.com.

- "Richard Pryor website". Richardpryor.com. Archived from the original on May 23, 2010. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Richard Pryor". Nndb.com. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- Jones, Steve (December 10, 2005). "Comedian Richard Pryor dies at 65". USA Today.

- ^ Als, Hilton (September 13, 1999). "A Pryor Love". The New Yorker.

- I Put a Spell on You: The Autobiography of Nina Simone. New York City: Pantheon Books. 1991. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0-679-41068-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - "Richard Pryor-Personal Life" Retrieved August 25, 2015

- Paul Green, "Richie Sets Multiplantium Record: Boston Has RIAA Top Debut Album," Billboard, November 15, 1986.

- "Richard Pryor Fast Facts". Yourdictionary. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- "Richard Pryor Emmy Winner". Television Academy.

- "SNL Transcripts: Richard Pryor: 12/13/75: Racist Word Association Interview". Snltranscripts.jt.org. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- "Richard Pryor clips".

- Silverman, David S. (2007). You Can't Air That: Four Cases of Controversy and Censorship in American Television Programming. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

- The word 'Nigger' – Richard Pryor & George Carlin on YouTube

- "Richard Pryor Ouster of Blacks Criticized". New York Times. Associated Press. December 17, 1983. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

Mr. Pryor announced in May that he had signed a five-year, $40 million production deal with Columbia Pictures and promised to open up opportunities for minorities at his Indigo Productions. …

- ^ Staff writer (December 10, 2005). "Comedian Richard Pryor Dead at 65 – Groundbreaking Black U.S. Comedian Richard Pryor Has Died after Almost 20 Years with Multiple Sclerosis". BBC News. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- Kiss Me Like a Stranger: My Search for Love and Art. St. Martin's Press. March 1, 2005. ISBN 978-0-312-33706-3.

- "Richard Pryor". GLBCY. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- "The Official Biography of Richard Pryor". Indigo, Inc. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- Writer, From a Times Staff (March 23, 1990). "Richard Pryor Suffers a Minor Heart Attack in Australia". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- "Richard Pryor Cracking Jokes After Triple Bypass". tribunedigital-orlandosentinel. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- "Interview with Rain Pryor". People. November 6, 2006. p. 76.

- "Richard Pryor biography". Hollywood.com.

- Scott Saul (December 9, 2014). Becoming Richard Pryor.

- Rabin, Nathan Rabin (March 3, 2009). "Random Roles: Margot Kidder (interview)". The A.V. Club.

- "The Norm Show – Norm vs. the Boxer". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved August 23, 2011.

- ^ http://explore.bfi.org.uk/4ce2b87cb041e

- ^ "Kings of Black Comedy", Oxford Film & Television.

- ^ http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P2-23491363.html

- ^ "Heroes of Black Comedy (TV Mini-Series) — Full Cast & Crew", IMDb.

- ^ Movie Details for '"Heroes of Black Comedy" Richard Pryor' (2002) Archived December 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, IMDb.

- "Heroes of Black Comedy (2002 TV Mini-Series) — Full Cast & Crew", IMDb.

- "Heroes of Black Comedy, The (2002)", TCM.

- "Richard Pryor – Evolution/Revolution: The Early Years (1966–1974) CD". CD Universe.

- "Richard Pryor". Richard Pryor. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- "Autopsy: The Last Hours Of Richard Pryor." Autopsy. Nar. Eric Meyers. Exec. Prod. Ed Taylor and Michael Kelpie. Reelz, March 25, 2017. Television.

- Zinoman, Jason (February 5, 2013). "Wild, Wired, Remembered A Richard Pryor Retrospective, 'A Pryor Engagement,' at BAM". The New York Times. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K2P6btsBdA8 At the end, the dedication is seen.

- "Taxes and Death' or Get Him to the Sunset Strip".

- "Richard Pryor: Omit the Logic, Internet Movie Database.com". Internet Movie Database. July 31, 2013.

- "Richard Pryor: Omit the Logic to Premiere Friday May 31 on Showtime". TVbytheNumbers.

- "All Voices Article July 5th 2010". Archived from the original on March 13, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Flick Direct article 10th September 2009

- Richard Pryor: Is It Something I Said? at IMDb

- "Lee Daniels To Direct Richard Pryor Biopic, Michael B. Jordan, Damon Wayans & Eddie Murphy in the Mix To Lead = The Playlist". January 10, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- "Lee Daniels' Richard Pryor biopic to star Mike Epps". BBC News. Retrieved August 28, 2014.

- "Richard Pryor to Get Posthumous Grammy Award". Voice of America. January 11, 2006. Archived from the original on September 13, 2008. Retrieved January 4, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Leslie Renken (May 1, 2015). "Long effort to honor Peoria-born comedian Richard Pryor culminates in Sunday unveiling". Peoria Journal Star. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

Further reading

- Saul, Scott (2015). Becoming Richard Pryor. New York: Harper. ISBN 9780062123305. OCLC 869267234.

External links

- Richard Pryor at IMDb

- Richard Pryor at the TCM Movie Database

- Richard Pryor: Stand-Up Philosopher, City Journal, Spring 2009

- Jennifer Lee Pryor at IMDb

- Post by Richard Pryor on his official website rebutting voice-loss rumors

- Richard Pryor's Legacy Lives On

- Bright Lights Film Journal career profile

- Richard Pryor at Emmys.com

- Richard Pryor at Find a Grave

- Richard Pryor's Peoria

- Richard Pryor: Icon (video). PBS. November 23, 2014. Biographical special—includes full version.

| Richard Pryor | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albums |

| ||||

| Concert films |

| ||||

| Television |

| ||||

| Films directed |

| ||||

| Films produced |

| ||||

| Films written |

| ||||

| Documentary films |

| ||||

| Mark Twain Prize winners | |

|---|---|

|

| Stax/Volt Records | |

|---|---|

| Major figures | |

| Related articles | |

- 1940 births

- 2005 deaths

- 20th-century American comedians

- 20th-century American male actors

- Actors from Peoria, Illinois

- African-American comedians

- African-American film directors

- African-American male actors

- African-American male comedians

- African-American military personnel

- African-American television producers

- African-American screenwriters

- African-American stand-up comedians

- American film directors

- American male film actors

- American male comedians

- American television producers

- American screenwriters

- American stand-up comedians

- American social commentators

- American television writers

- American male screenwriters

- American satirists

- American humorists

- Censorship in the arts

- Comedians from Illinois

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- Free speech activists

- Grammy Award winners

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Male actors from Illinois

- Mark Twain Prize recipients

- Neurological disease deaths in the United States

- Obscenity controversies in television

- People with multiple sclerosis

- Social critics

- Stax Records artists

- United States Army soldiers

- Warner Bros. Records artists

- Writers from Peoria, Illinois