| Revision as of 00:49, 20 September 2017 editPlyrStar93 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers46,828 editsm Reverted edits by 69.159.100.75 (talk) (HG) (3.3.0)Tag: Huggle← Previous edit | Revision as of 16:07, 25 September 2017 edit undo2001:630:301:a154::44 (talk) Changing newspeak to Esperanto -- as that is the obvious influence for Pravic...Tag: references removedNext edit → | ||

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

| Many conflicts occur between the freedom of anarchism and the constraints imposed by authority and society, both on Anarres and Urras. These constraints are both physical and social. Physically, Odo was imprisoned in the Fort in Drio for nine years, and the children construct their own prison in chapter two. Socially speaking, 'time after time the question of who is being locked out or in, which side of the wall one is on, is the focus of the narrative.' <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.depauw.edu/sfs/backissues/7/barbour7art.htm|title=Wholeness and Balance|last=Barbour|first=Douglas|publisher=Science Fiction Studies (1975)|accessdate=2016-10-27}}</ref> Mark Tunik emphasises that ''the wall'' is the dominant metaphor for these social constraints. Shevek hits ‘the wall of charm, courtesy, indifference.” He later notes that he let a “wall be built around him” that kept him from seeing the poor people on Urras. He had been co-opted, with walls of smiles of the rich, and he didn’t know how to break them down. Shevek at one point speculates that the people on Urras are not truly free, precisely because they have so many walls built between people and are so possessive. He says, “You are all in jail. Each alone, solitary, with a heap of what he owns. You live in prison, die in prison. It is all I can see in your eyes – the wall, the wall!” ‘ <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.academia.edu/7017991/The_New_Utopian_Politics_of_Ursula_K._Le_Guins_The_Dispossessed|title=The Need for Walls: Privacy, Community, and Freedom in The Dispossessed|last=Tunik|first=Mark|publisher=Lexington Books (2005)|accessdate=2016-10-27}}</ref> It is not just the state of mind of those inside the prisons that concerns Shevek, he also notes the effect on those outside the walls. Steve Grossi says, ‘by building a physical wall to keep the bad in, we construct a mental wall keeping ourselves, our thoughts, and our empathy out, to the collective detriment of all." Shevek himself later says, “those who build walls are their own prisoners.”<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.stevegrossi.com/on/the-dispossessed|title=The Dispossessed|last=Grossi|first=Steve|publisher=Steve Grossi (2013)|accessdate=2016-10-27}}</ref> Le Guin makes this explicit in chapter two, when the schoolchildren construct their own prison and detain one of their own inside. The deleterious effect on the children outside parallels the effect on the guards in the ] of 1971 (three years before ''The Dispossessed'' was published).<ref name="paul_brians2"></ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://doukhobor666.wordpress.com/2015/12/20/the-dispossessed/|title=The Dispossessed|publisher=Samizdat (2015)|accessdate=2016-10-28}}</ref> | Many conflicts occur between the freedom of anarchism and the constraints imposed by authority and society, both on Anarres and Urras. These constraints are both physical and social. Physically, Odo was imprisoned in the Fort in Drio for nine years, and the children construct their own prison in chapter two. Socially speaking, 'time after time the question of who is being locked out or in, which side of the wall one is on, is the focus of the narrative.' <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.depauw.edu/sfs/backissues/7/barbour7art.htm|title=Wholeness and Balance|last=Barbour|first=Douglas|publisher=Science Fiction Studies (1975)|accessdate=2016-10-27}}</ref> Mark Tunik emphasises that ''the wall'' is the dominant metaphor for these social constraints. Shevek hits ‘the wall of charm, courtesy, indifference.” He later notes that he let a “wall be built around him” that kept him from seeing the poor people on Urras. He had been co-opted, with walls of smiles of the rich, and he didn’t know how to break them down. Shevek at one point speculates that the people on Urras are not truly free, precisely because they have so many walls built between people and are so possessive. He says, “You are all in jail. Each alone, solitary, with a heap of what he owns. You live in prison, die in prison. It is all I can see in your eyes – the wall, the wall!” ‘ <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.academia.edu/7017991/The_New_Utopian_Politics_of_Ursula_K._Le_Guins_The_Dispossessed|title=The Need for Walls: Privacy, Community, and Freedom in The Dispossessed|last=Tunik|first=Mark|publisher=Lexington Books (2005)|accessdate=2016-10-27}}</ref> It is not just the state of mind of those inside the prisons that concerns Shevek, he also notes the effect on those outside the walls. Steve Grossi says, ‘by building a physical wall to keep the bad in, we construct a mental wall keeping ourselves, our thoughts, and our empathy out, to the collective detriment of all." Shevek himself later says, “those who build walls are their own prisoners.”<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.stevegrossi.com/on/the-dispossessed|title=The Dispossessed|last=Grossi|first=Steve|publisher=Steve Grossi (2013)|accessdate=2016-10-27}}</ref> Le Guin makes this explicit in chapter two, when the schoolchildren construct their own prison and detain one of their own inside. The deleterious effect on the children outside parallels the effect on the guards in the ] of 1971 (three years before ''The Dispossessed'' was published).<ref name="paul_brians2"></ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://doukhobor666.wordpress.com/2015/12/20/the-dispossessed/|title=The Dispossessed|publisher=Samizdat (2015)|accessdate=2016-10-28}}</ref> | ||

| The language spoken on the anarchist planet Anarres also reflects anarchism. ] is a ] in the tradition of ] |

The language spoken on the anarchist planet Anarres also reflects anarchism. ] is a ] in the tradition of ]. Pravic reflects many aspects of the philosophical foundations of utopian anarchism.<ref>Laurence, Davis and Peter G. Stillman. ''The New Utopian Politics of Ursula K. Le Guin's The Dispossessed'', Lexington Books (2005). Pp. 287-298.</ref> For instance, the use of the possessive case is strongly discouraged, a feature that also is reflected by the novel's title.<ref>Conley, Tim and Stephen Cain. ''Encyclopedia of Fictional and Fantastic Languages''. Greenwood Press, Westport (2006). Pp. 46-47.</ref> Children are trained to speak only about matters that interest others; anything else is "egoizing" (pp. 28–31). There is no property ownership of any kind. Shevek's daughter, upon meeting him for the first time, tells him, "You can share the handkerchief I use"<ref name="Dispossessed2">Ursula K. Le Guin, ''The Dispossessed'', p.69.</ref> rather than "You may borrow my handkerchief", thus conveying the idea that the handkerchief is not owned by the girl, but is merely used by her.<ref name="Burton-19852">Burton (1985).</ref> | ||

| === Utopianism === | === Utopianism === | ||

Revision as of 16:07, 25 September 2017

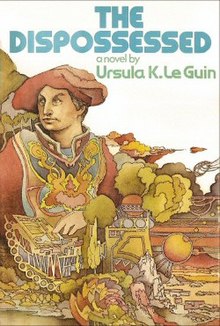

Cover of first edition (hardcover) Cover of first edition (hardcover) | |

| Author | Ursula K. Le Guin |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Fred Winkowski |

| Language | English |

| Series | The Hainish Cycle |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Published | 1974 (Harper & Row) |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Pages | 341 (first edition) |

| Awards | Locus Award for Best Novel (1975) |

| ISBN | 0-06-012563-2 (first edition, hardcover) |

| OCLC | 800587 |

| Preceded by | The Word for World is Forest |

| Followed by | Four Ways to Forgiveness |

The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia is a 1974 utopian science fiction novel by American writer Ursula K. Le Guin, set in the same fictional universe as that of The Left Hand of Darkness (the Hainish Cycle). The book won the Nebula Award for Best Novel in 1974, won both the Hugo and Locus Awards in 1975, and received a nomination for the John W. Campbell Memorial Award in 1975. It achieved a degree of literary recognition unusual for science fiction works due to its exploration of many themes, including anarchism and revolutionary societies, capitalism and individualism and collectivism.

It features the development of the mathematical theory underlying the fictional ansible, an instantaneous communications device that plays a critical role in Le Guin's Hainish Cycle. The invention of the ansible places the novel first in the internal chronology of the Hainish Cycle, although it was the fifth Hainish novel published.

Background

In her new introduction to the Library of America reprint in 2017, the author wrote:

- The Dispossessed started as a very bad short story, which I didn’t try to finish but couldn’t quite let go. There was a book in it, and I knew it, but the book had to wait for me to learn what I was writing about and how to write about it. I needed to understand my own passionate opposition to the war that we were, endlessly it seemed, waging in Vietnam, and endlessly protesting at home. If I had known then that my country would continue making aggressive wars for the rest of my life, I might have had less energy for protesting that one. But, knowing only that I didn’t want to study war no more, I studied peace. I started by reading a whole mess of utopias and learning something about pacifism and Gandhi and nonviolent resistance. This led me to the nonviolent anarchist writers such as Peter Kropotkin and Paul Goodman. With them I felt a great, immediate affinity. They made sense to me in the way Lao Tzu did. They enabled me to think about war, peace, politics, how we govern one another and ourselves, the value of failure, and the strength of what is weak.

- So, when I realised that nobody had yet written an anarchist utopia, I finally began to see what my book might be. And I found that its principal character, whom I’d first glimpsed in the original misbegotten story, was alive and well—my guide to Anarres.

Setting

The Dispossessed is set on Anarres and Urras, the twin inhabited worlds of Tau Ceti. Urras is divided into several states and dominated by its two largest, the rivals A-Io and Thu. The former has a capitalist economy and patriarchal system, and the latter is an authoritarian system that claims to rule in the name of the proletariat. A-Io has oppositional left-wing parties, one of which is closely linked to the rival society Thu.

The other world, Anarres, represents a third ideological structure: anarcho-syndicalist. Its society has weakened influenced due to their ancestors' self-imposed exile from Urras. Some citizens of A-Io contact the Anarresti protagonist Shevek, chiding him for betraying his beliefs by working at the university and accepting the government's hospitality.

A revolution sparks in the major, yet undeveloped third area of Benbili. A-Io invades the Thu-supported revolutionary area, generating a proxy war. Although there are a wide variety of political parties in A-Io, there are none on Anarres.

The plot

The story takes place on the fictional planet Urras and its habitable twin Anarres.

The chapters alternate between the worlds and in time. The even-numbered chapters, which are set on Anarres, take place first chronologically and are followed by the odd-numbered chapters, which take place on Urras. The only exceptions occurs in the first and last chapters, which take place in both worlds.

| Chapter numbers in chronological order |

|---|

| 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13 |

In order to forestall an anarcho-syndicalist rebellion, the major Urrasti states gave the revolutionaries (inspired by a visionary named Odo) the right to live on Anarres, along with a guarantee of non-interference, approximately two hundred years before the events of The Dispossessed. Before this, Anarres had had no permanent settlements apart from some mining facilities.

The economic and political situation of Anarres and its relation to Urras is ambiguous. The people of Anarres consider themselves as being free and independent, having broken off from the political and social influence of the old world. However, the powers of Urras consider Anarres as being essentially their mining colony, as the annual consignment of Anarres' precious metals and their distribution to major powers on Urras is a major economic event of the old world.

Anarres (chapters 1,2,4,6,8,10,12,13)

Chapter One begins in the middle of the story. The protagonist Shevek is a physicist attempting to develop a General Temporal Theory. The physics of the book describes time as having a much deeper, more complex structure than we understand it. It incorporates not only mathematics and physics, but also philosophy and ethics. Shevek finds his work blocked by a jealous superior, as his theories conflicts with the prevailing political philosophy and are thus distrusted by the society. His work is further disrupted by his obligation to perform manual labor during a drought in this anarchist society; in order to ensure survival in a harsh environment, the people of Anarres must put the needs of society ahead of their own personal desires, so Shevek performs hard agricultural labor in a dusty desert instead of working on his research. He arranges to go to Urras to finish and publish his theory.

Urras (chapters 1,3,5,7,9,11,13)

Arriving on Urras, Shevek is feted. Shevek soon finds himself disgusted with the social, sexual and political conventions of the hierarchical capitalist society of Urras. He joins in a labor protest that is violently suppressed, but he escapes to safety. Finally, he is sponsored by ambassadors of Terra who provide him safe passage back to Anarres.

Themes

Symbolism within The Dispossessed

The ambiguity of Anarres' economic and political situation in relation to Urras is symbolically manifested in the low wall surrounding Anarres' single spaceport. This wall is the only place on the anarchist planet where "No Trespassing!" signs may be seen, and it is where the book begins and ends. The people of Anarres believe that the wall divides a free world from the corrupting influence of an oppressor's ships. On the other hand, the wall could be a prison wall keeping the rest of the planet imprisoned and cut off. Shevek's life attempts to answer this question.

In addition to Shevek's journey to answer questions about his society's true level of freedom, the meaning of his theories themselves weave their way into the plot; they not only describe abstract physical concepts, but they also reflect ups and downs of the characters' lives, and the transformation of the Anarresti society. An oft-quoted saying in the book is "true journey is return." The meaning of Shevek's theories—which deal with the nature of time and simultaneity—have been subject to interpretation. For example, there have been interpretations that the non-linear nature of the novel is a reproduction of Shevek's theory.

Political Themes: Anarchy and Capitalism

Le Guin's foreword to the novel notes that her anarchism is closely akin to that of Peter Kropotkin's, whose Mutual Aid closely assessed the influence of the natural world on competition and cooperation.

Many conflicts occur between the freedom of anarchism and the constraints imposed by authority and society, both on Anarres and Urras. These constraints are both physical and social. Physically, Odo was imprisoned in the Fort in Drio for nine years, and the children construct their own prison in chapter two. Socially speaking, 'time after time the question of who is being locked out or in, which side of the wall one is on, is the focus of the narrative.' Mark Tunik emphasises that the wall is the dominant metaphor for these social constraints. Shevek hits ‘the wall of charm, courtesy, indifference.” He later notes that he let a “wall be built around him” that kept him from seeing the poor people on Urras. He had been co-opted, with walls of smiles of the rich, and he didn’t know how to break them down. Shevek at one point speculates that the people on Urras are not truly free, precisely because they have so many walls built between people and are so possessive. He says, “You are all in jail. Each alone, solitary, with a heap of what he owns. You live in prison, die in prison. It is all I can see in your eyes – the wall, the wall!” ‘ It is not just the state of mind of those inside the prisons that concerns Shevek, he also notes the effect on those outside the walls. Steve Grossi says, ‘by building a physical wall to keep the bad in, we construct a mental wall keeping ourselves, our thoughts, and our empathy out, to the collective detriment of all." Shevek himself later says, “those who build walls are their own prisoners.” Le Guin makes this explicit in chapter two, when the schoolchildren construct their own prison and detain one of their own inside. The deleterious effect on the children outside parallels the effect on the guards in the Stanford Prison Experiment of 1971 (three years before The Dispossessed was published).

The language spoken on the anarchist planet Anarres also reflects anarchism. Pravic is a constructed language in the tradition of Esperanto. Pravic reflects many aspects of the philosophical foundations of utopian anarchism. For instance, the use of the possessive case is strongly discouraged, a feature that also is reflected by the novel's title. Children are trained to speak only about matters that interest others; anything else is "egoizing" (pp. 28–31). There is no property ownership of any kind. Shevek's daughter, upon meeting him for the first time, tells him, "You can share the handkerchief I use" rather than "You may borrow my handkerchief", thus conveying the idea that the handkerchief is not owned by the girl, but is merely used by her.

Utopianism

The work is sometimes said to represent one of the few modern revivals of the utopian genre. When first published, the book included the tagline: "The magnificent epic of an ambiguous utopia!" which was shortened by fans to "An ambiguous utopia" and adopted as a subtitle in certain editions. There are also many characteristics of a utopian novel found in this book. For example, Shevek is an outsider when he arrives on Urras, which capitalizes on the utopian and scientific fiction theme of the "estrangement-setting".

Le Guin's utopianism, however, differs from the traditional "anarchist commune." Whereas most utopian novels attempt to convey a society that is absolutely good, this world differs as it is portray only as "ambiguously good."

Feminism

There is some disagreement as to whether The Dispossessed should be considered a feminist utopia or a feminist science fiction novel. According to Mary Morrison of the State University of New York at Buffalo, the anarchist themes in this book help to promote feminist themes as well. Other critics, such as Professor William Marcellino of SUNY Buffalo and Sarah Lefanu, writer of "Popular Writing and Feminist Intervention in Science Fiction," argue that there are distinct anti-feminist undertones throughout the novel.

Morrison argues that Le Guin's portrayed ideals of Taoism, the celebration of labor and the body, and desire or sexual freedom in an anarchist society contribute greatly to the book's feminist message. Taoism, which rejects dualisms and divisions in favor of a Yin and Yang balance, brings attention to the balance between not only the two planets, but between the male and female inhabitants. The celebration of labor on Anarres stems from a celebration of a mother's labor, focusing on creating life rather than on building objects. The sexual freedom on Anarres also contributes to the book's feminist message.

On the other hand, some critics believe that Le Guin's feminist themes are either weak or not present. Some believe that the Taoist interdependence between the genders actually weakens Le Guin's feminist message. Marcellino believes that the anarchist themes in the novel take precedence and dwarf any feminist themes. Lefanu adds that there is a difference between the feminist messages that the book explicitly presents and the anti-feminist undertones. For example, the book says that women created the society on Anarres. However, female characters seem secondary to the male protagonist, who seems to be a traditional male hero; this subversion weakens the any feminist message that Le Guin was trying to convey.

The Title

It has been suggested that Le Guin's title is a reference to Dostoyevsky's novel about anarchists, Demons (Template:Lang-ru, Bésy), one popular English-language translation of which is titled The Possessed. Much of the philosophical underpinnings and ecological concepts came from Murray Bookchin's Post-Scarcity Anarchism (1971), according to a letter Le Guin sent to Bookchin. Anarres citizens are dispossessed not just by political choice, but by the very lack of actual resources to possess. Here, again, Le Guin draws a contrast with the natural wealth of Urras, and the competitive behaviors this fosters.

Proposed time

In the last chapter of The Dispossessed, we learn that the Hainish people arrived at Tau Ceti 60 years previously, which is more than 150 years after the secession of the Odonians from Urras and their exodus to Anarres. Terrans are also there, and the novel occurs some time in the future, according to an elaborate chronology worked out by science fiction author Ian Watson in 1975: "the baseline date of AD 2300 for The Dispossessed is taken from the description of Earth in that book (§11) as having passed through an ecological and social collapse with a population peak of 9 billion to a low-population but highly centralized recovery economy." In the same article, Watson assigns a date of AD 4870 to The Left Hand of Darkness; both dates are problematic - as Watson says himself, they are contradicted by "Genly Ai's statement that Terrans 'were ignorant until about three thousand years ago of the uses of zero' ".

Reception

The novel received generally positive reviews. Baird Searles characterized the novel as an "extraordinary work", saying Le Guin had "created a working society in exquisite detail" and "a fully realized hypothetical culture living breathing characters who are inevitable products of that culture". Gerald Jonas, writing in The New York Times, said that "Le Guin's book, written in her solid, no-nonsense prose, is so persuasive that it ought to put a stop to the writing of prescriptive Utopias for at least 10 years". Theodore Sturgeon praised The Dispossessed as "a beautifully written, beautifully composed book", saying "it performs one of prime functions, which is to create another kind of social system to see how it would work. Or if it would work." Lester del Rey, however, gave the novel a mixed review, citing the quality of Le Guin's writing but claiming that the ending "slips badly", a deus ex machina that "destroy much of the strength of the novel".

Translations

- Bulgarian: Освободеният

- Chinese (Simplified): 一无所有, 2009

- Chinese (Traditional): 一無所有, 2005

- Croatian: Ljudi bez ičega, 2009

- Czech: Vyděděnec, 1995

- Danish: De udstødte : en socialistisk utopi, 1979

- Dutch: De Ontheemde

- Finnish: Osattomien planeetta, 1979

- French: Les Dépossédés, 1975

- German: Planet der Habenichtse, 1976 later Die Enteigneten, 2006, later Freie Geister, 2017

- Greek: Ο αναρχικός των δύο κόσμων

- Hebrew: המנושל, 1980 later בידיים ריקות 2015

- Hungarian: A kisemmizettek, 1994

- Italian: I reietti dell'altro pianeta, later Quelli di Anarres, 1976

- Japanese: 所有せざる人々, 1986

- Korean: 빼앗긴 자들, 2002

- Polish: Wydziedziczeni

- Portuguese: Os Despossuídos, Os Despojados

- Romanian: Deposedaţii, 1995

- Russian: Обездоленные, 1994, Обделённые, 1997

- Serbian: Čovek praznih šaka, 1987

- Spanish: Los desposeídos, 1983

- Swedish: Shevek, 1976

- Turkish: Mülksüzler, 1990

Other versions

In 1987, the CBC Radio anthology program Vanishing Point adapted The Dispossessed into a series of six 30 minute episodes.

See also

- Hainish cycle novels

- Rocannon's World, 1966

- Planet of Exile, 1966

- City of Illusions, 1967

- The Left Hand of Darkness, 1969

- The Word for World is Forest, 1976

- Four Ways to Forgiveness, 1995

- The Telling, 2000

- Other works

- Themes

References

- Notes

- "1974 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ "1975 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- In The Word for World is Forest, the newly created ansible is brought to Athshe, a planet being settled by Earth-humans. In other tales in the Hainish Cycle, the ansible already exists. The word "ansible" was coined in Rocannon's World (first in order of publication but third in internal chronology), where it is central to the plot.

- “Introduction” from Ursula K. Le Guin: The Hainish Novels & Stories, Volume One, retrieved 9/8/2017

- The story is told in Le Guin's "The Day Before the Revolution".

- Said by Shevek near the end of Chapter 13

- Rigsby, Ellen M. (2005), p. 169

- Peter Kropotkin, Mutual Aid (1902).

- Barbour, Douglas. "Wholeness and Balance". Science Fiction Studies (1975). Retrieved 2016-10-27.

- Tunik, Mark. "The Need for Walls: Privacy, Community, and Freedom in The Dispossessed". Lexington Books (2005). Retrieved 2016-10-27.

- Grossi, Steve. "The Dispossessed". Steve Grossi (2013). Retrieved 2016-10-27.

- ^ "Study Guide for Ursula LeGuin: The Dispossessed (1974)" - Paul Brians

- "The Dispossessed". Samizdat (2015). Retrieved 2016-10-28.

- Laurence, Davis and Peter G. Stillman. The New Utopian Politics of Ursula K. Le Guin's The Dispossessed, Lexington Books (2005). Pp. 287-298.

- Conley, Tim and Stephen Cain. Encyclopedia of Fictional and Fantastic Languages. Greenwood Press, Westport (2006). Pp. 46-47.

- Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed, p.69.

- Burton (1985).

- Davis and Stillman (2005).

- Book review discussing meanings

- Penn State University Press listing

- ^ "Judah Bierman- Ambiguity in Utopia: The Dispossessed". www.depauw.edu. Retrieved 2017-05-12.

- Morrison, Mary I. Anarcho-Feminism and Permanent Revolution in Ursula K. Le Guin's ‘‘The Dispossessed’’, State University of New York at Buffalo, Ann Arbor, 2011, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global, https://search.proquest.com/docview/878894517.

- Marcellino, William. "Shadows to Walk: Ursula Le Guin's Transgressions in Utopia." The Journal of American Culture, vol. 32, no. 3, 2009, pp. 203-213, Music Periodicals Database; Performing Arts Periodicals Database, https://search.proquest.com/docview/200658410.

- Lefanu, Sarah. "Popular Writing and Feminist Intervention in Science Fiction." Gender, Genre and Narrative Pleasure. Ed. Derek Longhurst. Vol. 9. New York: Routledge, 2012. 177-92. Print.

- Janet Biehl, Bookchin biographer; letter in UKL archive

- Mathiesen.

- Watson, Ian (March 1975). "Le Guin's Lathe of Heaven and the Role of Dick: The False Reality as Mediator". Science Fiction Studies # 5 = Volume 2, Part 1. Retrieved 2017-02-26.

- "The Dispossessed: Visit from A Small Planet", Village Voice, November 21, 1974, pp.56, 58

- "Of Things to Come", The New York Times Book Review, October 26, 1975

- "Galaxy Bookshelf", Galaxy Science Fiction, June 1974, pp.97-98

- "Reading Room", If, August 1974, pp.144-45

- Times Past Old Time Radio Archives.

- Bibliography

- Anarchism and The Dispossessed

- John P. Brennan, "Anarchism and Utopian Tradition in The Dispossessed", pp. 116–152, in Olander & Greenberg, editors, Ursula K. Le Guin, New York: Taplinger (1979).

- Samuel R. Delany, "To Read The Dispossessed," in The Jewel-Hinged Jaw. N.Y.: Dragon Press, 1977, pp. 239–308 (anarchism in The Dispossessed). (pdf available online through Project Muse)

- Neil Easterbrook, "State, Heterotopia: The Political Imagination in Heinlein, Le Guin, and Delany", pp. 43–75, in Hassler & Wilcox, editors, Political Science Fiction, Columbia, SC: U of South Carolina Press (1997).

- Leonard M. Fleck, "Science Fiction as a Tool of Speculative Philosophy: A Philosophic Analysis of Selected Anarchistic and Utopian Themes in Le Guin's The Dispossessed", pp. 133–45, in Remington, editor, Selected Proceedings of the 1978 Science Fiction Research Association National Conference, Cedar Falls: Univ. of Northern Iowa (1979).

- John Moore, "An Archaeology of the Future: Ursula Le Guin and Anarcho-Primitivism", Foundation: The Review of Science Fiction, v.63, pp. 32–39 (Spring 1995).

- Larry L. Tifft, "Possessed Sociology and Le Guin's Dispossessed: From Exile to Anarchism", pp. 180–197, in De Bolt & Malzberg, editors, Voyager to Inner Lands and to Outer Space, Port Washington, NY: Kennikat (1979).

- Kingsley Widmer, "The Dialectics of Utopianism: Le Guin's The Dispossessed", Liberal and Fine Arts Review, v.3, nos.1–2, pp. 1–11 (Jan.–July 1983).

- Gender and The Dispossessed

- Lillian M. Heldreth, "Speculations on Heterosexual Equality: Morris, McCaffrey, Le Guin", pp. 209–220 in Palumbo, ed., Erotic Universe: Sexuality and Fantastic Literature, Westport, CT: Greenwood (1986).

- Neil Easterbrook, "State, Heterotopia: The Political Imagination in Heinlein, Le Guin, and Delany", pp. 43–75, in Hassler & Wilcox, editors, Political Science Fiction, Columbia, SC: U of South Carolina Press (1997).

- Mario Klarer, "Gender and the 'Simultaneity Principle': Ursula Le Guin's The Dispossessed", Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature, v.25, n.2, pp. 107–21 (Spring 1992).

- Jim Villani, "The Woman Science Fiction Writer and the Non-Heroic Male Protagonist", pp. 21–30 in Hassler, ed., Patterns of the Fantastic, Mercer Island, WA: Starmont House (1983).

- Language and The Dispossessed

- Deirdre Burton, "Linguistic Innovation in Feminist Science Fiction", Ilha do Desterro: Journal of Language and Literature, v.14, n.2, pp. 82–106 (1985).

- Property and possessions

- Werner Christie Mathiesen, "The Underestimation of Politics in Green Utopias: The Description of Politics in Huxley's Island, Le Guin's The Dispossessed, and Callenbach's Ecotopia", Utopian Studies: Journal of the Society for Utopian Studies, v.12, n.1, pp. 56–78 (2001).

- Science and The Dispossessed

- Ellen M. Rigsby, "Time and the Measure of the Political Animal." The New Utopian Politics of Ursula K. Le Guin's The Dispossessed. Ed., Laurence Davis and Peter Stillman. Lanham: Lexington books., 2005.

- Taoism and The Dispossessed

- Elizabeth Cummins Cogell, "Taoist Configurations: The Dispossessed", pp. 153–179 in De Bolt & Malzberg, editors, Ursula K. Le Guin: Voyager to Inner Lands and to Outer Space, Port Washington, NY: Kennikat (1979).

- Utopian literature and The Dispossessed

- James W. Bittner, "Chronosophy, Ethics, and Aesthetics in Le Guin's The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia, pp. 244–270 in Rabkin, Greenberg, and Olander, editors, No Place Else: Explorations in Utopian and Dystopian Fiction, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press (1983).

- John P. Brennan, "Anarchism and Utopian Tradition in The Dispossessed", pp. 116–152, in Olander & Greenberg, editors, Ursula K. Le Guin, New York: Taplinger (1979).

- Bülent Somay, "Towards an Open-Ended Utopia", Science-Fiction Studies, v.11, n.1 (#32), pp. 25–38 (March 1984).

- Peter Fitting, "Positioning and Closure: On the 'Reading Effect' of Contemporary Utopian Fiction", Utopian Studies, v.1, pp. 23–36 (1987).

- Kingsley Widmer, "The Dialectics of Utopianism: Le Guin's The Dispossessed", Liberal and Fine Arts Review, v.3, nos.1–2, pp. 1–11 (Jan.–July 1983).

- L. Davis and P. Stillman, editors, "The new utopian politics of Ursula K. Le Guin's The Dispossessed", Lexington Books, (2005).

- Additional references

- Judah Bierman, "Ambiguity in Utopia: The Dispossessed", Science-Fiction Studies, v.2, pp. 249–255 (1975).

- James F. Collins, "The High Points So Far: An Annotated Bibliography of Ursula K. LeGuin's The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed", Bulletin of Bibliography, v.58, no.2, pp. 89–100 (June 2001).

- James P. Farrelly, "The Promised Land: Moses, Nearing, Skinner, and Le Guin", JGE: The Journal of General Education, v.33, n.1, pp. 15–23 (Spring 1981).

External links

- Full text of The Dispossessed at Libcom.org

- The Dispossessed title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Audio review and discussion of The Dispossessed at The Science Fiction Book Review Podcast

- Readable maps of Anarres and Urras

- The Dispossessed at Worlds Without End

- CBC Radio Vanishing Point audio production of The Dispossessed at the Internet Archive: Part 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

| Hugo Award for Best Novel | |

|---|---|

| Retro |

|

| 1950s |

|

| 1960s |

|

| 1970s |

|

| 1980s |

|

| 1990s |

|

| 2000s |

|

| 2010s |

|

| 2020s |

|

| Locus Award for Best Novel | |

|---|---|

| |

|

| Nebula Award for Best Novel | |

|---|---|

| 1966–1980 |

|

| 1981–2000 |

|

| 2001–2020 |

|

| 2021–present |

|

- 1974 American novels

- Anarchist fiction

- Hainish Cycle

- Hugo Award for Best Novel-winning works

- 1970s science fiction novels

- Social science fiction

- Nebula Award for Best Novel-winning works

- Prometheus Award-winning works

- Utopian novels

- Anarcho-communism

- Novels by Ursula K. Le Guin

- Harper & Row books

- Libertarian books

- Tau Ceti in fiction

- Locus Award-winning works