| Revision as of 20:06, 4 November 2018 editRosguill (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators144,052 edits Adding short description: "Pore-forming toxin found in the earthworm Eisenia fetida" (Shortdesc helper)← Previous edit | Revision as of 17:55, 6 November 2018 edit undoMunguira (talk | contribs)32 editsm I revised the ingles and I removed doble citations.Next edit → | ||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

| {{citation style|date=November 2018}} | {{citation style|date=November 2018}} | ||

| Lysenin is a ] in the ] of the earthworm '']''. |

'''Lysenin''' is a ] in the ] of the earthworm '']''. | ||

| ==Lysenin monomer== | ==Lysenin monomer== | ||

| Lysenin is a protein produced in the coelomocytes- |

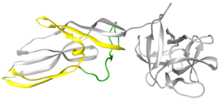

Lysenin is a protein produced in the coelomocytes-leucocyte of animals with coelom-of ''Eisenia fetida''.<ref>Yilmaz, N., Yamaji-Hasegawa, A., Hullin-Matsuda, F. & Kobayashi, T. Molecular mechanisms of action of sphingomyelin-specific pore-forming toxin, lysenin. in Seminars in cell & developmental biology (Elsevier, 2017).</ref> This protein was first isolated from the coelomic fluid by Yoshiyuki Sekizawa from Kobayashi group in 1996, who named the protein lysenin (lysis+Eisenia).<ref>SEKIZAWA, Y., HAGIWARA, K., NAKAJIMA, T. & KOBAYASHI, H. A novel protein, lysenin, that causes contraction of the isolated rat aorta: its purification from the coelomic fluid of the earthworm, Eisenia foetida. Biomedical Research 17, 197–203 (1996).</ref> Lysenin is relatively small with a molecular weight of 33 kDa (Figure 1). The X-ray structure of lysenin was first determined by de Colibus ''et al.'', and structurally classified as a member of Aerolysin family, with which shares structure and function.<ref>De Colibus, L. et al. Structures of lysenin reveal a shared evolutionary origin for pore-forming proteins and its mode of sphingomyelin recognition. Structure 20, 1498–1507 (2012).</ref> From a structural point of view, lysenin monomers are formed by a receptor binding domain (right globular part, Figure 1) and a Pore Forming Module (rest of the molecule, Figure 1); domains shared by the rest of Aerolysin family.<ref>De Colibus, L. et al. Structures of lysenin reveal a shared evolutionary origin for pore-forming proteins and its mode of sphingomyelin recognition. Structure 20, 1498–1507 (2012).</ref> Lysenin monomer shows three sphingomyelin different binding motifs in the receptor binding domain. | ||

| The part of the monomer that forms part of the β-barrel have been clarify after obtaining Lysenin pore structure.<ref>Bokori-Brown, M. et al. Cryo-EM structure of lysenin pore elucidates membrane insertion by an aerolysin family protein. Nat Commun 7: 11293–11296. (2016).</ref> At first, the so-called β-hairpin was alleged to be a small region in the vicinity of the Pore Forming Module (shown in green in Figure 1). Currently, it is known that the β-barrel is formed by a larger region (shown in yellow in Figure 1). | |||

| The definition of PFM changed after extracting the Lysenin pore structure. The domain that forms the β-barrel, the so-called β-hairpin, was alleged to be a small region in the vicinity of the PFM (shown in green in Figure 1). Nowadays, it is known that the β-barrel is formed by a larger region, including also regions in the middle of the PFM (illustrated in yellow in Figure 1). | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| Line 14: | Line 13: | ||

| ==Lysenin membrane receptors== | ==Lysenin membrane receptors== | ||

| The natural membrane target of Lysenin is an animal plasma membrane lipid called Sphingomyelin, with at least three Phosphatidylcholines (PC) groups from sphingomyelin.<ref>Ishitsuka, R. & Kobayashi, T. Cholesterol and lipid/protein ratio control the oligomerization of a sphingomyelin-specific toxin, lysenin. Biochemistry 46, 1495–1502 (2007).</ref> Sphingomyelin is usually found associated to cholesterol in lipid rafts.<ref>Simons, K. & Gerl, M. J. Revitalizing membrane rafts: new tools and insights. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 11, nrm2977 (2010).</ref> Cholesterol, which enhances oligomerization, provides a stable platform with high lateral mobility where the monomer-monomer encounters are more probable.<ref>Ishitsuka, R. & Kobayashi, T. Cholesterol and lipid/protein ratio control the oligomerization of a sphingomyelin-specific toxin, lysenin. Biochemistry 46, 1495–1502 (2007).</ref> | |||

| The natural target of Lysenin is an animal plasma membrane lipid called ].] Sphingomyelin is synthesized in the ], and is mostly present in the outer leaflet of the animal plasma membrane, where it plays an important role as a secondary messenger.]<sup>,]</sup> | |||

| PFTs have shown to be able to remodel the membrane structure,<ref>Ros, U. & García-Sáez, A. J. More than a pore: the interplay of pore-forming proteins and lipid membranes. The Journal of membrane biology 248, 545–561 (2015).</ref> sometimes even mixing lipid phases.<ref>Yilmaz, N. & Kobayashi, T. Visualization of lipid membrane reorganization induced by a pore-forming toxin using high-speed atomic force microscopy. ACS nano 9, 7960–7967 (2015).</ref> In the case of lysenin, the detergent belt, the part of the β-barrel occupied by detergent in the Cryogenic Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) study of Lysenin pore,<ref>Bokori-Brown, M. et al. Cryo-EM structure of lysenin pore elucidates membrane insertion by an aerolysin family protein. Nat Commun 7: 11293–11296. (2016).</ref> is 32 Å in height. On the other hand, sphingomyelin/Cholesterol bilayers are about 4.5 nm height.<ref>Quinn, P. J. Structure of sphingomyelin bilayers and complexes with cholesterol forming membrane rafts. Langmuir 29, 9447–9456 (2013).</ref> This difference in height between the detergent belt and the Sphingomyelin/Cholesterol bilayer implies a bend of the membrane in the region surrounding the pore , called negative mismatch.<ref>Guigas, G. & Weiss, M. Effects of protein crowding on membrane systems. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes 1858, 2441–2450 (2016).</ref> This bending results in a net attraction between pores that induce aggregation.<ref>Munguira, I. L. B., Barbas, A. & Casuso, ignacio. Mechanism of blocking and unblocking of the pore formation of the toxin lysenin regulated by local crowdingThermometry at the nanoscale. Nanoscale 4, 4799–4829 (2018).</ref> | |||

| In the raft, lipids are in liquid-ordered phase, meaning more lateral dense packed, rigid, low chain motion and high lateral mobility. This rigidity is in part due to the high transition temperature of sphingolipids, as well as the interactions of these lipids with ].] Cholesterol is a relatively small, amphipathic molecule that can accommodate between the large acyl chains of sphingolipids, resulting in the so-called liquid ordered phase. | |||

| Cholesterol plays an important role in the oligomerization of Lysenin.] This sterol provides a stable platform with high lateral mobility were the monomer-monomer encounters are more probable.]<sup>,]</sup> | |||

| PFT have been shown to be able to remodel the membrane structure, even mixing lipid phases.] The detergent belt-the part of the β-barrel occupied by detergent in the Cryogenic Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) study- of Lysenin pore is 32 Å in height.] This height implies a bend of the membrane in the region surrounding the pore, call negative mismatch.] | |||

| PFT membrane targets are found to be part of lipid raft.] This membrane microdomains boost monomer density facilitating PFT oligomerization. | |||

| ==Lysenin binding, oligomerization and insertion== | ==Lysenin binding, oligomerization and insertion== | ||

| Membrane binding is a requisite to initiate PFT oligomerization. Lysenin monomers bind specifically to sphingomyelin via the receptor binding domain.<ref>De Colibus, L. et al. Structures of lysenin reveal a shared evolutionary origin for pore-forming proteins and its mode of sphingomyelin recognition. Structure 20, 1498–1507 (2012).</ref> The final Lysenin oligomer is constituted by nine monomers without quantified deviations, as shown for the first time by Munguira ''et al.''<ref>Munguira, I. et al. Glasslike Membrane Protein Diffusion in a Crowded Membrane. ACS Nano 10, 2584–2590 (2016).</ref> Lysenin monomers bind to sphingomyelin-enriched domains, which provide a stable platform with a high lateral mobility, hence favouring the oligomerization.<ref>Ishitsuka, R. & Kobayashi, T. Cholesterol and lipid/protein ratio control the oligomerization of a sphingomyelin-specific toxin, lysenin. Biochemistry 46, 1495–1502 (2007).</ref> lysenin oligomerization occurs in a two-step process, as for proteins in general. The oligomerization process was recently imaged qualitatively.<ref>Munguira, I. L. B., Barbas, A. & Casuso, ignacio. Mechanism of blocking and unblocking of the pore formation of the toxin lysenin regulated by local crowdingThermometry at the nanoscale. Nanoscale 4, 4799–4829 (2018).</ref> | |||

| Membrane attachment is a requisite to initiate oligomerization. Lysenin monomers bind specifically to sphingomyelin via the receptor binding domain. How lysenin oligomerization happens remains an open question, due to the current technical limitations for recording monomer diffusion. | |||

| First, the monomers adsorb to the membrane by specific interactions, resulting in monomers concentration increased. This increase is promoted by the small area where the membrane receptor accumulates owing to the fact that the majority of PFT membrane receptors are associated with lipid rafts.<ref>Lafont, F. & Van Der Goot, F. G. Bacterial invasion via lipid rafts. Cellular microbiology 7, 613–620 (2005).</ref> Another side effect, aside from the increase of monomer concentration, is the monomer-monomer interaction increase that boosts lysenin oligomerization. After a critical concentration is reached, several oligomers are formed simultaneously, as recently show by Munguira ''et al.''<ref>Munguira, I. L. B., Barbas, A. & Casuso, ignacio. Mechanism of blocking and unblocking of the pore formation of the toxin lysenin regulated by local crowdingThermometry at the nanoscale. Nanoscale 4, 4799–4829 (2018).</ref> Complete oligomers consist in nine monomers, although incomplete oligomerization process was also observed by Yilmaz ''et al.''<ref>Yilmaz, N. et al. Real-time visualization of assembling of a sphingomyelin-specific toxin on planar lipid membranes. Biophysical journal 105, 1397–1405 (2013).</ref> In contrast to PFT of cholesterol dependent cytolysin family,<ref>Mulvihill, E., van Pee, K., Mari, S. A., Müller, D. J. & Yildiz, Ö. Directly observing the lipid-dependent self-assembly and pore-forming mechanism of the cytolytic toxin listeriolysin O. Nano letters 15, 6965–6973 (2015).</ref> lysenin incomplete oligomer evolution to complete oligomers was never observed. | |||

| A complete oligomerization results in the so-called prepore state, placed on the membrane. Determine the structure by X-ray or Cryo-EM of the prepore is a challenging process that so far has not produce any results. The only available information about the prepore structure was provided by Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM). The measured prepore height was 90 Å; and the width 118 Å, with an inner pore of 50 Å (Figure 2).<ref>Yilmaz, N. et al. Real-time visualization of assembling of a sphingomyelin-specific toxin on planar lipid membranes. Biophysical journal 105, 1397–1405 (2013).</ref> A model of the prepore, proposed by Podobnik ''et al.'',<ref>Podobnik, M. et al. Crystal structure of an invertebrate cytolysin pore reveals unique properties and mechanism of assembly. Nature communications 7, 11598 (2016).</ref> was built aligning monomer structure (PDB ID 3ZXD) with the pore structure (PDB ID 5GAQ) by their receptor-binding domains (residues 160 to 297). Interestingly though, a recent study in aerolysin points out that the currently accepted model for the lysenin prepore should be revisited, according to the new available data on the aerolysin insertion.<ref>Iacovache, M. I. et al. Cryo-EM structure of aerolysin variants reveals a novel protein fold and the pore-formation process. Nature communications 7, 12062 (2016).</ref> Furthermore, a recent study has proved that lysenin prepore and prepore to pore models should be changed to fit recent observations.<ref>Munguira, I. L. B., Barbas, A. & Casuso, ignacio. Mechanism of blocking and unblocking of the pore formation of the toxin lysenin regulated by local crowdingThermometry at the nanoscale. Nanoscale 4, 4799–4829 (2018).</ref> | |||

| The final Lysenin oligomer is constituted by nine monomers without quantified deviations, as shown for the first time by Munguira ''et al''.] | |||

| A conformational change transforms the PFM to the transmembrane β-barrel, leading to the pore state.<ref>Bokori-Brown, M. et al. Cryo-EM structure of lysenin pore elucidates membrane insertion by an aerolysin family protein. Nat Commun 7: 11293–11296. (2016).</ref> Such a conformational change produces a decrease in the oligomer height of 2.5 nm according to AFM measurements.<ref>Yilmaz, N. et al. Real-time visualization of assembling of a sphingomyelin-specific toxin on planar lipid membranes. Biophysical journal 105, 1397–1405 (2013).</ref> The main dimensions, using lysenin pore X-ray structure, are height 97 Å, width 115 Å and the inner pore of 30 Å (Figure 2).<ref>Bokori-Brown, M. et al. Cryo-EM structure of lysenin pore elucidates membrane insertion by an aerolysin family protein. Nat Commun 7: 11293–11296. (2016).</ref> Remarkably, the complete oligomerization is not a requisite for the insertion, although incomplete oligomers in the pore state can be found.<ref>Yilmaz, N. et al. Real-time visualization of assembling of a sphingomyelin-specific toxin on planar lipid membranes. Biophysical journal 105, 1397–1405 (2013).</ref> The trigger mechanism for the prepore to pore transition in lysenin depends on three glutamic acids (E92, E94 and E97), and is activated by a decrease in pH,<ref>Munguira, I. L. B., Takahashi, H., Casuso, I. & Scheuring, S. Lysenin Toxin Membrane Insertion Is pH-Dependent but Independent of Neighboring Lysenins. Biophysical Journal 113, 2029–2036 (2017).</ref> from physiological conditions to the acidic conditions reached after endocytosis. These three glutamic acids are located in an α-helix that forms part of the PFM, and are found in all aerolysin family members in its PFMs. The prepore to pore transition can be blocked if the membrane reaches certain density of oligomers, a mechanism first observed by Munguira ''et al.'',<ref>Munguira, I. L. B., Barbas, A. & Casuso, ignacio. Mechanism of blocking and unblocking of the pore formation of the toxin lysenin regulated by local crowdingThermometry at the nanoscale. Nanoscale 4, 4799–4829 (2018).</ref> that could be general to all β-PFTs. | |||

| Lysenin monomers bind to sphingomyelin-enriched domains, which provide a stable platform with a high lateral mobility, hence favouring the oligomerization. Lysenin oligomerization occurs in a two-step process, as for proteins in general.]<sup>,]</sup> | |||

| ] | |||

| First, the monomers adsorb to the membrane by specific interactions, resulting in an increased concentration. Lipid rafts are believed to play a key role contributing to the increasing of the monomer concentration. After a critical concentration is reached, several oligomers are formed simultaneously. The second step consists in the growth of new oligomers. It takes places in the borders of the oligomers cluster. | |||

| A complete oligomerization results in a prepore. To determine the structure by X-ray or Cryo-EM of the prepore is a challenging process that till the date did not produce any result. The only available information about the prepore structure was provided by Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM).] The measured prepore height was 90 Å]<sup>,]</sup> and the width 118 Å, with an inner pore of 50 Å (Figure 2).<sup>3,14</sup> Interestingly, a recent study in Aerolysin points out that the currently accepted model for the Lysenin prepore should be revisited, according to the new available data about the Aerolysin insertion.] | |||

| ] | |||

| A conformational change transforms the PFM in the transmembrane β-barrel, leading to the pore state. Such a conformational change produces a decrease of the oligomer height of , according to AFM measurements.] Using X-ray structure, they were measured the main dimensions, being height 97 Å, width 115 Å and the inner pore of 30 Å (Figure 2).] Interestingly, the complete oligomerization is not a requisite for the insertion. It is usual to observe incomplete oligomers in prepore and pore states ]<sup>,]</sup>. However, the incomplete pores did not evolve to complete, a phenomenon that was observed in CDCs family.] The triggering mechanism for the prepore to pore transition in Lysenin depend in three glutamic acids (E92, E94 and E97), and is activate by a decreased of pH], from physiological conditions. This residues are located in an α-helix that form part of the PFM. | |||

| A conformational change transforms the PFM in the transmembrane β-barrel, leading to the pore state. Such a conformational change produces a decrease of the oligomer height of , according to AFM measurements.] Using X-ray structure, they were measured the main dimensions, being height 97 Å, width 115 Å and the inner pore of 30 Å (Figure 2).] Interestingly, the complete oligomerization is not a requisite for the insertion. It is usual to observe incomplete oligomers in prepore and pore states ]<sup>,]</sup>. However, the incomplete pores did not evolve to complete, a phenomenon that was observed in CDCs family.] The triggering mechanism for the prepore to pore transition in Lysenin depend in three glutamic acids (E92, E94 and E97), and is activate by a decreased of pH], from physiological conditions. This residues are located in an α-helix that form part of the PFM. | |||

| ==Lysenin insertion consequences== | ==Lysenin insertion consequences== | ||

| The ultimate consequences caused by |

The ultimate consequences caused by lysenin pore formation are not well documented; however, there are three the plausible consequences, | ||

| *Punch the membrane breaks the sphingomyelin asymmetry between the two leaflets of the lipid bilayer, which cause the cell to enter in apoptosis.<ref>Green, D. R. Apoptosis and sphingomyelin hydrolysis: the flip side. J Cell Biol 150, F5–F8 (2000).</ref> PFTs are supposed to induce lipid flip-flop that can also break the sphingomyelin asymmetry.<ref>Ros, U. & García-Sáez, A. J. More than a pore: the interplay of pore-forming proteins and lipid membranes. The Journal of membrane biology 248, 545–561 (2015).</ref> | |||

| *Increase the calcium concentration in the cytoplasm, drives to apoptosis.<ref>Orrenius, S., Zhivotovsky, B. & Nicotera, P. Calcium: Regulation of cell death: the calcium–apoptosis link. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 4, 552 (2003).</ref> | |||

| *Decrease the potassium concentration in the cytoplasm causes apoptosis.<ref>Yu, S. P. Regulation and critical role of potassium homeostasis in apoptosis. Progress in neurobiology 70, 363–386 (2003).</ref> | |||

| ==Biological role of lysenin== | |||

| * To punch the membrane breaks the sphingomyelin asymmetry between the two leaflets of the lipid bilayer, which leads to apoptosis.]<sup>6</sup> PFT are supposed to induce lipid flip-flop that can also break the sphingomyelin asymmetry.] | |||

| * The presence of the pore increases the calcium concentration in the cytoplasm, which drives to apoptosis. <sup>]</sup> | |||

| * A decrease in the potassium concentration in the cytoplasm causes apoptosis.] | |||

| ==Biological role of Lysenin== | |||

| The biological role of Lysenin still remains unknown. It was suggested that Lysenin can play a role as a defeat mechanism against attackers such as bacteria, fungi or small invertebrates.] Nevertheless, sphingomyelin starts to appear in the plasma membrane of chordates.] Therefore, Lysenin, being dependent on sphingomyelin as a binding factor, cannot affect bacteria, fungi or in general invertebrates. Another hypothesis is that the earthworm, which is able to expel coelomic fluid under stress,]<sup>,]</sup> generates an avoidance behaviour to its vertebrate predators (like birds, hedgehogs or moles).] In that case, the expelled Lysenin could be more effective if the coelomic fluid reaches the eye, where the concentration of sphingomyelin is ten times higher than in other body organs.] | |||

| Related to this, coelomic fluid, exuded under stressful situations by the earthworm, has a pungent smell -that gives name to the earthworm- was suggested to be an antipredator adaptation.] In any case, if Lysenin plays a role generating an avoiding behaviour, remains unknown. | |||

| The biological role of lysenin still remains unknown. It was suggested that lysenin can play a role as a defeat mechanism against attackers such as bacteria, fungi or small invertebrates.<ref>Ballarin, L. & Cammarata, M. Lessons in immunity: from single-cell organisms to mammals. (Academic Press, 2016).</ref> Nevertheless, sphingomyelin starts to appear in the plasma membrane of chordates.<ref>Kobayashi, H., Sekizawa, Y., Aizu, M. & Umeda, M. Lethal and non-lethal responses of spermatozoa from a wide variety of vertebrates and invertebrates to lysenin, a protein from the coelomic fluid of the earthworm Eisenia foetida. Journal of Experimental Zoology 286, 538–549 (2000).</ref> Therefore, lysenin, being dependent on sphingomyelin as a binding factor, cannot affect bacteria, fungi or in general invertebrates. Another hypothesis is that the earthworm, which is able to expel coelomic fluid under stress,<ref>Sukumwang, N. & Umezawa, K. Earthworm-derived pore-forming toxin Lysenin and screening of its inhibitors. Toxins 5, 1392–1401 (2013).</ref> <ref>Kobayashi, H., Ohta, N. & Umeda, M. Biology of lysenin, a protein in the coelomic fluid of the earthworm Eisenia foetida. International review of cytology 236, 45–99 (2004).</ref> generates an avoidance behaviour to its vertebrate predators (such as birds, hedgehogs or moles).<ref>Swiderska, B. et al. Lysenin family proteins in earthworm coelomocytes–Comparative approach. Developmental & Comparative Immunology 67, 404–412 (2017).</ref> If that is the case, the expelled lysenin might be more effective if the coelomic fluid reached the eye, where the concentration of sphingomyelin is ten times higher than in other body organs.<ref>Berman, E. R. Biochemistry of the Eye. (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).</ref> A complementary hypothesis is that the coelomic fluid, exuded under stressful situations by the earthworm, which has a pungent smell -that gives name to the earthworm- was suggested to be an antipredator adaptation. It remains unknown whether (or not) if lysenin plays a role generating an avoiding behaviour, remains unknown.<ref>Edwards, C. A. & Bohlen, P. J. Biology and Ecology of Earthworms. (Springer Science & Business Media, 1996).</ref> | |||

| == References == | == References == | ||

| <!--- See ] on how to create references using<ref></ref> tags which will then appear here automatically --> | |||

| 1. Sekizawa, Y., Hagiwara, K., Nakajima, T. & Kobayashi, H. "A Novel Protein, Lysenin, That Causes Contraction of the Isolated Rat Aorta : Its Puriification from the Coleomic Fluid of the Earthworm, ''Eisenia foetida''". ''Biomedical research'' 17, 197–203 (1996). | |||

| 2. De Colibus, L. et al. "Structures of Lysenin Reveal a Shared Evolutionary Origin for Pore-Forming Proteins And Its Mode of Sphingomyelin Recognition" . ''Structure'' 20, 1498–1507 (2012). | |||

| 3. Bernheimer, A. W. & Avigad, L. S. "Partial Characterization of Aerolysin, a Lytic Exotoxin from ''Aeromonas hydrophila''". ''Infection and Immunity'', 1016–1021 (1974). | |||

| 4. Parker, M.W. et al. "Structure of the ''Aeromonas'' toxin in its water-soluble and membrane-channel states". ''Nature'' 367, 292–295 (1994). | |||

| 5. Szczesny, P. et al. "Extending the Aerolysin Family: From Bacteria to Vertebrates". ''PLoS ONE'' 6, 1–10 (2011). | |||

| 6. Bokori-Brown, M. et al. "Cryo-EM structure of lysenin pore elucidates membrane insertion by an aerolysin family protein". ''Nature Communications'' 7, 11293 (2016). | |||

| 7. Podobnik, M. et al. "Crystal structure of an invertebrate cytolysin pore reveals unique properties and mechanism of assembly". ''Nature Communications'' 7, 11598 (2016). | |||

| 8. Yamaji, A. et al. "Lysenin, a Novel Sphingomyelin-specific Binding Protein". ''The Journal of Biological Chemistry'' 273, 5300–5306 (1998). | |||

| 9. Murate, M. & Kobayashi, T. "Revisiting transbilayer distribution of lipids in the plasma membrane". ''Chemistry and Physics of Lipids'' 194, 58–71 (2016). | |||

| 10. "Sphingomyelin breakdown and cell fate". ''Trends in Biochemical Sciences'' 21, 468–471 (1996). | |||

| 11. Slotte, J. P. "The importance of hydrogen bonding in sphingomyelin's membrane interactions with co-lipids". ''Biochimica et Biophysica Acta'' 1858, 304–10 (2016). | |||

| 12. Ishitsuka, R. & Kobayashi, T. "Cholesterol and lipid/protein ratio control the oligomerization of a sphingomyelin-specific toxin, lysenin". ''Biochemistry'' 46, 1495–1502 (2007). | |||

| 13. Yamaji-Hasegawa, A. et al. "Oligomerization and Pore Formation of a Sphingomyelin-specific Toxin, Lysenin". ''Journal of Biological Chemistry'' 278, 22762–22770 (2003). | |||

| 14. Rojko, N. & Anderluh, G. "How Lipid Membranes Affect Pore Forming Toxin Activity". ''Accounts of Chemical Research'' 48, 3073–9 (2015). | |||

| 15. Ros, U. & Garcia-Saez, A.J. "More Than a Pore: The Interplay of Pore-Forming Proteins and Lipid Membranes". ''The Journal of Membrane Biology'' 248, 545–61 (2015). | |||

| 16. Guigas, G. & Weiss, M. "Effects of protein crowding on membrane systems". ''Biochimica et Biophysica Acta'' 1858, 2441–50 (2016). | |||

| 17. Phillips, R., Ursell, T., Wiggins, P. & Sens, P. "Emerging roles for lipids in shaping membrane-protein function". ''Nature'' 459, 379–385 (2009). | |||

| 18.Lafont, Frank, Laurence Abrami, and F. Gisou van der Goot. "Bacterial subversion of lipid rafts." Current opinion in microbiology 7, no. 1 (2004): 4-10. | |||

| 19. Munguira, I. et al. "Glasslike Membrane Protein Diffusion in a Crowded Membrane". ''ACS Nano'' 10, 2584–90 (2016). | |||

| 20. Wolde, P. R. t. "Enhancement of Protein Crystal Nucleation by Critical Density Fluctuations". ''Science'' 277, 1975–1978 (1997). | |||

| 21. Chunga, S., Shin, S.-H., Bertozzi, C. R. & Yoreo, J. J. D. 'Self-catalyzed growth of S layers via an amorphousto-crystalline transition limited by folding kinetics". ''Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America'' 107, 16536–16541 (2010). | |||

| 22. Yilmaz, N. et al. "Real-Time Visualization of Assembling of a Sphingomyelin-Specific Toxin on Planar Lipid Membranes". ''Biophysical Journal'' 105, 1397–1405 (2013). | |||

| 23. Iacovache, I. et al. "Cryo-EM structure of aerolysin variants reveals a novel protein fold and the pore-formation process". ''Nature Communications'' 7, 12062 (2016). | |||

| 24. Kyte, J. & Doolittle, R. F. "A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein". ''Journal of Molecular Biology'' 157, 105–132 (1982). | |||

| 25. Mulvihill, E., van Pee, K., Mari, S.A., Muller, D. J. & Yildiz, O. "Directly Observing the Lipid-Dependent Self-Assembly and Pore-Forming Mechanism of the Cytolytic Toxin Listeriolysin" O. ''Nano Letters'' 15, 6965–73 (2015). | |||

| 26. Munguira, I. L. B., Takahashi, H., Casuso, I. & Scheuring, S. "Lysenin Toxin Membrane Insertion Is pH-Dependent but Independent of Neighboring Lysenins". ''Biophysical Journal'' 113, 2029–2036 (2017). | |||

| 27. Green, D. R. "Apoptosis and Sphingomyelin Hydrolysis: The Flip Side". ''The Journal of Cell Biology'' 150, F5–F7 (2000). | |||

| 28. Orrenius, S., Zhivotovsky, B. & Nicotera, P. "Regulation of cell death: the calcium-apoptosis link". ''Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology'' 4, 552–65 (2003). | |||

| 29. Yu, S.P. "Regulation and critical role of potassium homeostasis in apoptosis". ''Progress in Neurobiology'' 70, 363–386 (2003). | |||

| 30. Ballarin, L. & Cammarata, M. ''Lessons in Immunity: From Single-cell Organisms to Mammals''. (Academic Press, 2016). | |||

| 31. Kobayashi, H., Sekizawa, Y., Aizu, M. & Umeda, M. "Lethal and Non-Lethal Responses of Spermatozoa From a Wide Variety of Vertebrates and Invertebrates to Lysenin, a Protein From the Coelomic Fluid of the Earthworm ''Eisenia foetida''". ''Journal of Experimental Zoology'' 286, 538–549 (2000). | |||

| 32. Sukumwang, N. & Umezawa, K. "Earthworm-derived pore-forming toxin lysenin and screening of its inhibitors". ''Toxins (Basel)'' 5, 1392–401 (2013). | |||

| 33. Kobayashi, H., Ohta, N. & Umeda, M. "Biology of Lysenin, a Protein in the Coelomic Fluid of the Earthworm ''Eisenia foetida''". ''International Review of Cytology'' 236, 45–99 (2004). | |||

| 34. Swiderska, B. et al. "Lysenin family proteins in earthworm coelomocytes - Comparative approach". ''Developmental & Comparative Immunology'' 67, 404–412 (2017). | |||

| 35. Berman, E. R. ''Biochemistry of the eye''. (1991). | |||

| 36. Edwards, C. A. & Bohlen, P. J. ''Biology and Ecology of Earthworms'', Volume 3. ''Springer Science & Business Media'', 426 (1996). | |||

| {{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

Revision as of 17:55, 6 November 2018

Pore-forming toxin found in the earthworm Eisenia fetida| This article has an unclear citation style. The references used may be made clearer with a different or consistent style of citation and footnoting. (November 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Lysenin is a Pore-forming toxin in the coelomic fluid of the earthworm Eisenia fetida.

Lysenin monomer

Lysenin is a protein produced in the coelomocytes-leucocyte of animals with coelom-of Eisenia fetida. This protein was first isolated from the coelomic fluid by Yoshiyuki Sekizawa from Kobayashi group in 1996, who named the protein lysenin (lysis+Eisenia). Lysenin is relatively small with a molecular weight of 33 kDa (Figure 1). The X-ray structure of lysenin was first determined by de Colibus et al., and structurally classified as a member of Aerolysin family, with which shares structure and function. From a structural point of view, lysenin monomers are formed by a receptor binding domain (right globular part, Figure 1) and a Pore Forming Module (rest of the molecule, Figure 1); domains shared by the rest of Aerolysin family. Lysenin monomer shows three sphingomyelin different binding motifs in the receptor binding domain. The part of the monomer that forms part of the β-barrel have been clarify after obtaining Lysenin pore structure. At first, the so-called β-hairpin was alleged to be a small region in the vicinity of the Pore Forming Module (shown in green in Figure 1). Currently, it is known that the β-barrel is formed by a larger region (shown in yellow in Figure 1).

Lysenin membrane receptors

The natural membrane target of Lysenin is an animal plasma membrane lipid called Sphingomyelin, with at least three Phosphatidylcholines (PC) groups from sphingomyelin. Sphingomyelin is usually found associated to cholesterol in lipid rafts. Cholesterol, which enhances oligomerization, provides a stable platform with high lateral mobility where the monomer-monomer encounters are more probable. PFTs have shown to be able to remodel the membrane structure, sometimes even mixing lipid phases. In the case of lysenin, the detergent belt, the part of the β-barrel occupied by detergent in the Cryogenic Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) study of Lysenin pore, is 32 Å in height. On the other hand, sphingomyelin/Cholesterol bilayers are about 4.5 nm height. This difference in height between the detergent belt and the Sphingomyelin/Cholesterol bilayer implies a bend of the membrane in the region surrounding the pore , called negative mismatch. This bending results in a net attraction between pores that induce aggregation.

Lysenin binding, oligomerization and insertion

Membrane binding is a requisite to initiate PFT oligomerization. Lysenin monomers bind specifically to sphingomyelin via the receptor binding domain. The final Lysenin oligomer is constituted by nine monomers without quantified deviations, as shown for the first time by Munguira et al. Lysenin monomers bind to sphingomyelin-enriched domains, which provide a stable platform with a high lateral mobility, hence favouring the oligomerization. lysenin oligomerization occurs in a two-step process, as for proteins in general. The oligomerization process was recently imaged qualitatively. First, the monomers adsorb to the membrane by specific interactions, resulting in monomers concentration increased. This increase is promoted by the small area where the membrane receptor accumulates owing to the fact that the majority of PFT membrane receptors are associated with lipid rafts. Another side effect, aside from the increase of monomer concentration, is the monomer-monomer interaction increase that boosts lysenin oligomerization. After a critical concentration is reached, several oligomers are formed simultaneously, as recently show by Munguira et al. Complete oligomers consist in nine monomers, although incomplete oligomerization process was also observed by Yilmaz et al. In contrast to PFT of cholesterol dependent cytolysin family, lysenin incomplete oligomer evolution to complete oligomers was never observed.

A complete oligomerization results in the so-called prepore state, placed on the membrane. Determine the structure by X-ray or Cryo-EM of the prepore is a challenging process that so far has not produce any results. The only available information about the prepore structure was provided by Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM). The measured prepore height was 90 Å; and the width 118 Å, with an inner pore of 50 Å (Figure 2). A model of the prepore, proposed by Podobnik et al., was built aligning monomer structure (PDB ID 3ZXD) with the pore structure (PDB ID 5GAQ) by their receptor-binding domains (residues 160 to 297). Interestingly though, a recent study in aerolysin points out that the currently accepted model for the lysenin prepore should be revisited, according to the new available data on the aerolysin insertion. Furthermore, a recent study has proved that lysenin prepore and prepore to pore models should be changed to fit recent observations.

A conformational change transforms the PFM to the transmembrane β-barrel, leading to the pore state. Such a conformational change produces a decrease in the oligomer height of 2.5 nm according to AFM measurements. The main dimensions, using lysenin pore X-ray structure, are height 97 Å, width 115 Å and the inner pore of 30 Å (Figure 2). Remarkably, the complete oligomerization is not a requisite for the insertion, although incomplete oligomers in the pore state can be found. The trigger mechanism for the prepore to pore transition in lysenin depends on three glutamic acids (E92, E94 and E97), and is activated by a decrease in pH, from physiological conditions to the acidic conditions reached after endocytosis. These three glutamic acids are located in an α-helix that forms part of the PFM, and are found in all aerolysin family members in its PFMs. The prepore to pore transition can be blocked if the membrane reaches certain density of oligomers, a mechanism first observed by Munguira et al., that could be general to all β-PFTs.

Lysenin insertion consequences

The ultimate consequences caused by lysenin pore formation are not well documented; however, there are three the plausible consequences,

- Punch the membrane breaks the sphingomyelin asymmetry between the two leaflets of the lipid bilayer, which cause the cell to enter in apoptosis. PFTs are supposed to induce lipid flip-flop that can also break the sphingomyelin asymmetry.

- Increase the calcium concentration in the cytoplasm, drives to apoptosis.

- Decrease the potassium concentration in the cytoplasm causes apoptosis.

Biological role of lysenin

The biological role of lysenin still remains unknown. It was suggested that lysenin can play a role as a defeat mechanism against attackers such as bacteria, fungi or small invertebrates. Nevertheless, sphingomyelin starts to appear in the plasma membrane of chordates. Therefore, lysenin, being dependent on sphingomyelin as a binding factor, cannot affect bacteria, fungi or in general invertebrates. Another hypothesis is that the earthworm, which is able to expel coelomic fluid under stress, generates an avoidance behaviour to its vertebrate predators (such as birds, hedgehogs or moles). If that is the case, the expelled lysenin might be more effective if the coelomic fluid reached the eye, where the concentration of sphingomyelin is ten times higher than in other body organs. A complementary hypothesis is that the coelomic fluid, exuded under stressful situations by the earthworm, which has a pungent smell -that gives name to the earthworm- was suggested to be an antipredator adaptation. It remains unknown whether (or not) if lysenin plays a role generating an avoiding behaviour, remains unknown.

References

- Yilmaz, N., Yamaji-Hasegawa, A., Hullin-Matsuda, F. & Kobayashi, T. Molecular mechanisms of action of sphingomyelin-specific pore-forming toxin, lysenin. in Seminars in cell & developmental biology (Elsevier, 2017).

- SEKIZAWA, Y., HAGIWARA, K., NAKAJIMA, T. & KOBAYASHI, H. A novel protein, lysenin, that causes contraction of the isolated rat aorta: its purification from the coelomic fluid of the earthworm, Eisenia foetida. Biomedical Research 17, 197–203 (1996).

- De Colibus, L. et al. Structures of lysenin reveal a shared evolutionary origin for pore-forming proteins and its mode of sphingomyelin recognition. Structure 20, 1498–1507 (2012).

- De Colibus, L. et al. Structures of lysenin reveal a shared evolutionary origin for pore-forming proteins and its mode of sphingomyelin recognition. Structure 20, 1498–1507 (2012).

- Bokori-Brown, M. et al. Cryo-EM structure of lysenin pore elucidates membrane insertion by an aerolysin family protein. Nat Commun 7: 11293–11296. (2016).

- Ishitsuka, R. & Kobayashi, T. Cholesterol and lipid/protein ratio control the oligomerization of a sphingomyelin-specific toxin, lysenin. Biochemistry 46, 1495–1502 (2007).

- Simons, K. & Gerl, M. J. Revitalizing membrane rafts: new tools and insights. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 11, nrm2977 (2010).

- Ishitsuka, R. & Kobayashi, T. Cholesterol and lipid/protein ratio control the oligomerization of a sphingomyelin-specific toxin, lysenin. Biochemistry 46, 1495–1502 (2007).

- Ros, U. & García-Sáez, A. J. More than a pore: the interplay of pore-forming proteins and lipid membranes. The Journal of membrane biology 248, 545–561 (2015).

- Yilmaz, N. & Kobayashi, T. Visualization of lipid membrane reorganization induced by a pore-forming toxin using high-speed atomic force microscopy. ACS nano 9, 7960–7967 (2015).

- Bokori-Brown, M. et al. Cryo-EM structure of lysenin pore elucidates membrane insertion by an aerolysin family protein. Nat Commun 7: 11293–11296. (2016).

- Quinn, P. J. Structure of sphingomyelin bilayers and complexes with cholesterol forming membrane rafts. Langmuir 29, 9447–9456 (2013).

- Guigas, G. & Weiss, M. Effects of protein crowding on membrane systems. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes 1858, 2441–2450 (2016).

- Munguira, I. L. B., Barbas, A. & Casuso, ignacio. Mechanism of blocking and unblocking of the pore formation of the toxin lysenin regulated by local crowdingThermometry at the nanoscale. Nanoscale 4, 4799–4829 (2018).

- De Colibus, L. et al. Structures of lysenin reveal a shared evolutionary origin for pore-forming proteins and its mode of sphingomyelin recognition. Structure 20, 1498–1507 (2012).

- Munguira, I. et al. Glasslike Membrane Protein Diffusion in a Crowded Membrane. ACS Nano 10, 2584–2590 (2016).

- Ishitsuka, R. & Kobayashi, T. Cholesterol and lipid/protein ratio control the oligomerization of a sphingomyelin-specific toxin, lysenin. Biochemistry 46, 1495–1502 (2007).

- Munguira, I. L. B., Barbas, A. & Casuso, ignacio. Mechanism of blocking and unblocking of the pore formation of the toxin lysenin regulated by local crowdingThermometry at the nanoscale. Nanoscale 4, 4799–4829 (2018).

- Lafont, F. & Van Der Goot, F. G. Bacterial invasion via lipid rafts. Cellular microbiology 7, 613–620 (2005).

- Munguira, I. L. B., Barbas, A. & Casuso, ignacio. Mechanism of blocking and unblocking of the pore formation of the toxin lysenin regulated by local crowdingThermometry at the nanoscale. Nanoscale 4, 4799–4829 (2018).

- Yilmaz, N. et al. Real-time visualization of assembling of a sphingomyelin-specific toxin on planar lipid membranes. Biophysical journal 105, 1397–1405 (2013).

- Mulvihill, E., van Pee, K., Mari, S. A., Müller, D. J. & Yildiz, Ö. Directly observing the lipid-dependent self-assembly and pore-forming mechanism of the cytolytic toxin listeriolysin O. Nano letters 15, 6965–6973 (2015).

- Yilmaz, N. et al. Real-time visualization of assembling of a sphingomyelin-specific toxin on planar lipid membranes. Biophysical journal 105, 1397–1405 (2013).

- Podobnik, M. et al. Crystal structure of an invertebrate cytolysin pore reveals unique properties and mechanism of assembly. Nature communications 7, 11598 (2016).

- Iacovache, M. I. et al. Cryo-EM structure of aerolysin variants reveals a novel protein fold and the pore-formation process. Nature communications 7, 12062 (2016).

- Munguira, I. L. B., Barbas, A. & Casuso, ignacio. Mechanism of blocking and unblocking of the pore formation of the toxin lysenin regulated by local crowdingThermometry at the nanoscale. Nanoscale 4, 4799–4829 (2018).

- Bokori-Brown, M. et al. Cryo-EM structure of lysenin pore elucidates membrane insertion by an aerolysin family protein. Nat Commun 7: 11293–11296. (2016).

- Yilmaz, N. et al. Real-time visualization of assembling of a sphingomyelin-specific toxin on planar lipid membranes. Biophysical journal 105, 1397–1405 (2013).

- Bokori-Brown, M. et al. Cryo-EM structure of lysenin pore elucidates membrane insertion by an aerolysin family protein. Nat Commun 7: 11293–11296. (2016).

- Yilmaz, N. et al. Real-time visualization of assembling of a sphingomyelin-specific toxin on planar lipid membranes. Biophysical journal 105, 1397–1405 (2013).

- Munguira, I. L. B., Takahashi, H., Casuso, I. & Scheuring, S. Lysenin Toxin Membrane Insertion Is pH-Dependent but Independent of Neighboring Lysenins. Biophysical Journal 113, 2029–2036 (2017).

- Munguira, I. L. B., Barbas, A. & Casuso, ignacio. Mechanism of blocking and unblocking of the pore formation of the toxin lysenin regulated by local crowdingThermometry at the nanoscale. Nanoscale 4, 4799–4829 (2018).

- Green, D. R. Apoptosis and sphingomyelin hydrolysis: the flip side. J Cell Biol 150, F5–F8 (2000).

- Ros, U. & García-Sáez, A. J. More than a pore: the interplay of pore-forming proteins and lipid membranes. The Journal of membrane biology 248, 545–561 (2015).

- Orrenius, S., Zhivotovsky, B. & Nicotera, P. Calcium: Regulation of cell death: the calcium–apoptosis link. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 4, 552 (2003).

- Yu, S. P. Regulation and critical role of potassium homeostasis in apoptosis. Progress in neurobiology 70, 363–386 (2003).

- Ballarin, L. & Cammarata, M. Lessons in immunity: from single-cell organisms to mammals. (Academic Press, 2016).

- Kobayashi, H., Sekizawa, Y., Aizu, M. & Umeda, M. Lethal and non-lethal responses of spermatozoa from a wide variety of vertebrates and invertebrates to lysenin, a protein from the coelomic fluid of the earthworm Eisenia foetida. Journal of Experimental Zoology 286, 538–549 (2000).

- Sukumwang, N. & Umezawa, K. Earthworm-derived pore-forming toxin Lysenin and screening of its inhibitors. Toxins 5, 1392–1401 (2013).

- Kobayashi, H., Ohta, N. & Umeda, M. Biology of lysenin, a protein in the coelomic fluid of the earthworm Eisenia foetida. International review of cytology 236, 45–99 (2004).

- Swiderska, B. et al. Lysenin family proteins in earthworm coelomocytes–Comparative approach. Developmental & Comparative Immunology 67, 404–412 (2017).

- Berman, E. R. Biochemistry of the Eye. (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).

- Edwards, C. A. & Bohlen, P. J. Biology and Ecology of Earthworms. (Springer Science & Business Media, 1996).