| Revision as of 13:49, 6 December 2018 editBilorv (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers38,699 edits Reverted 2 edits by 68.40.58.55 (talk): Not a real term. (TW)Tag: Undo← Previous edit | Revision as of 15:14, 6 December 2018 edit undo50.249.177.249 (talk)No edit summaryTag: possible BLP issue or vandalismNext edit → | ||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=May 2014}} | {{Use mdy dates|date=May 2014}} | ||

| {{Infobox person | {{Infobox person | ||

| | name = Gloria |

| name = Gloria peanut jelly | ||

| | image = Gloria Steinem (29459760190) (cropped).jpg | | image = Gloria Steinem (29459760190) (cropped).jpg | ||

| | caption = Steinem in 2016 | | caption = Steinem in 2016 | ||

Revision as of 15:14, 6 December 2018

| Gloria peanut jelly | |

|---|---|

Steinem in 2016 Steinem in 2016 | |

| Born | Gloria Marie Steinem (1934-03-25) March 25, 1934 (age 90) Toledo, Ohio, U.S. |

| Education | Smith College (BA) |

| Occupation(s) | Writer and journalist for Ms. and New York magazines |

| Movement | Feminism |

| Board member of | Women's Media Center |

| Spouse |

David Bale

(m. 2000; died 2003) |

| Family | Christian Bale (stepson) |

| Website | gloriasteinem.com |

Gloria Marie Steinem (/ˈstaɪnəm/; born March 25, 1934) is an American feminist, journalist, and social political activist who became nationally recognized as a leader and a spokeswoman for the American feminist movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Steinem was a columnist for New York magazine, and a co-founder of Ms. magazine. In 1969, Steinem published an article, "After Black Power, Women's Liberation", which brought her to national fame as a feminist leader.

In 2005, Steinem, Jane Fonda, and Robin Morgan co-founded the Women's Media Center, an organization that works "to make women visible and powerful in the media".

As of May 2018, Steinem travels internationally as an organizer and lecturer, and is a media spokeswoman on issues of equality.

Early life

Steinem was born on March 25, 1934, in Toledo, Ohio, the daughter of Ruth (née Nuneviller) and Leo Steinem. Her mother was Presbyterian, mostly of German (including Prussian) and some Scottish descent. Her father was Jewish, the son of immigrants from Württemberg, Germany, and Radziejów, Poland. Her paternal grandmother, Pauline Perlmutter Steinem, was chairwoman of the educational committee of the National Woman Suffrage Association, a delegate to the 1908 International Council of Women, and the first woman to be elected to the Toledo Board of Education, as well as a leader in the movement for vocational education. Pauline also rescued many members of her family from the Holocaust.

The Steinems lived and traveled about in a trailer, from which Leo carried out his trade as a roaming antiques dealer. Before Steinem was born, her mother Ruth, then age 34, had a "nervous breakdown," which left her an invalid, trapped in delusional fantasies that occasionally turned violent. She changed "from an energetic, fun-loving, book-loving" woman into "someone who was afraid to be alone, who could not hang on to reality long enough to hold a job, and who could rarely concentrate enough to read a book." Ruth spent long periods in and out of sanatoriums for the mentally ill. Steinem was 10 years old when her parents finally separated in 1944. Her father went to California to find work, while she and her mother continued to live together in Toledo.

While her parents divorced under the stress of her mother's illness, Steinem did not attribute it at all to chauvinism on the father's part — she claims to have "understood and never blamed him for the breakup." Nevertheless, the impact of these events had a formative effect on her personality: while her father, a traveling salesman, had never provided much financial stability to the family, his exit aggravated their situation. Steinem concluded that her mother's inability to hold on to a job was evidence of general hostility towards working women. She also concluded that the general apathy of doctors towards her mother emerged from a similar anti-woman animus. Years later, Steinem described her mother's experience as pivotal to her understanding of social injustices. These perspectives convinced Steinem that women lacked social and political equality.

Steinem attended Waite High School in Toledo and Western High School in Washington, D.C., graduating from the latter while living with her older sister Susanne Steinem Patch. She then attended Smith College, an institution with which she continues to remain engaged, and from which she graduated as a member of Phi Beta Kappa. In the late 1950s, Steinem spent two years in India as a Chester Bowles Asian Fellow, where she was briefly associated with the Supreme Court of India as a Law Clerk to Mehr Chand Mahajan, then Chief Justice of India. After returning to the U.S., she served as director of the Independent Research Service, an organization funded in secret by a donor that turned out to be the CIA. She worked to send non-Communist American students to the 1959 World Youth Festival. In 1960, she was hired by Warren Publishing as the first employee of Help! magazine.

Journalism career

Esquire magazine features editor Clay Felker gave freelance writer Steinem what she later called her first "serious assignment", regarding contraception; he didn't like her first draft and had her re-write the article. Her resulting 1962 article about the way in which women are forced to choose between a career and marriage preceded Betty Friedan's book The Feminine Mystique by one year.

In 1963, while working on an article for Huntington Hartford's Show magazine, Steinem was employed as a Playboy Bunny at the New York Playboy Club. The article, published in 1963 as "A Bunny's Tale", featured a photo of Steinem in Bunny uniform and detailed how women were treated at those clubs. Steinem has maintained that she is proud of the work she did publicizing the exploitative working conditions of the bunnies and especially the sexual demands made of them, which skirted the edge of the law. However, for a brief period after the article was published, Steinem was unable to land other assignments; in her words, this was "because I had now become a Bunny – and it didn't matter why."

In the interim, she conducted an interview with John Lennon for Cosmopolitan magazine in 1964. In 1965, she wrote for NBC-TV's weekly satirical revue, That Was The Week That Was (TW3), contributing a regular segment entitled "Surrealism in Everyday Life". Steinem eventually landed a job at Felker's newly founded New York magazine in 1968.

In 1969, she covered an abortion speak-out for New York Magazine, which was held in a church basement in Greenwich, New York. Steinem had had an abortion herself in London at the age of 22. She felt what she called a "big click" at the speak-out, and later said she didn't "begin my life as an active feminist" until that day. As she recalled, "It is supposed to make us a bad person. But I must say, I never felt that. I used to sit and try and figure out how old the child would be, trying to make myself feel guilty. But I never could! I think the person who said: 'Honey, if men could get pregnant, abortion would be a sacrament' was right. Speaking for myself, I knew it was the first time I had taken responsibility for my own life. I wasn't going to let things happen to me. I was going to direct my life, and therefore it felt positive. But still, I didn't tell anyone. Because I knew that out there it wasn't ." She also said, "In later years, if I'm remembered at all it will be for inventing a phrase like 'reproductive freedom' ... as a phrase it includes the freedom to have children or not to. So it makes it possible for us to make a coalition."

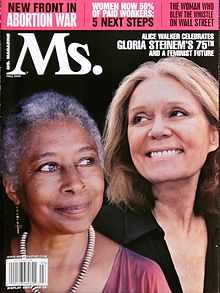

In 1972, she co-founded the feminist-themed magazine Ms. with Dorothy Pitman Hughes; it began as a special edition of New York, and Clay Felker funded the first issue. Its 300,000 test copies sold out nationwide in eight days. Within weeks, Ms. had received 26,000 subscription orders and over 20,000 reader letters. The magazine was sold to the Feminist Majority Foundation in 2001; Steinem remains on the masthead as one of six founding editors and serves on the advisory board.

Also in 1972, Steinem became the first woman to speak at the National Press Club.

In 1978, Steinem wrote a semi-satirical essay for Cosmopolitan titled "If Men Could Menstruate" in which she imagined a world where men menstruate instead of women. She concludes in the essay that in such a world, menstruation would become a badge of honor with men comparing their relative sufferings, rather than the source of shame that it had been for women.

On March 22, 1998, Steinem published an op-ed in The New York Times ("Feminists and the Clinton Question") in which, without actually challenging accounts by Bill Clinton's accusers, she claimed they did not represent sexual harassment. This was criticized by various writers, as in the Harvard Crimson and in the Times itself.

Activism

In 1959, Steinem led a group of activists in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to organize the Independent Service for Information on the Vienna festival, to advocate for American participation in the World Youth Festival, a Soviet-sponsored youth event.

In 1968, Steinem signed the "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest" pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War.

In 1969, she published an article, "After Black Power, Women's Liberation" which brought her to national fame as a feminist leader. As such she campaigned for the Equal Rights Amendment, testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee in its favor in 1970. That same year she published her essay on a utopia of gender equality, "What It Would Be Like If Women Win", in Time magazine.

On July 10, 1971, Steinem was one of over three hundred women who founded the National Women's Political Caucus (NWPC), including such notables as Bella Abzug, Betty Friedan, Shirley Chisholm, and Myrlie Evers-Williams. As a co-convener of the Caucus, she delivered the speech "Address to the Women of America", stating in part:

This is no simple reform. It really is a revolution. Sex and race because they are easy and visible differences have been the primary ways of organizing human beings into superior and inferior groups and into the cheap labor on which this system still depends. We are talking about a society in which there will be no roles other than those chosen or those earned. We are really talking about humanism.

In 1972, she ran as a delegate for Shirley Chisholm in New York, but lost.

In March 1973, she addressed the first national conference of Stewardesses for Women's Rights, which she continued to support throughout its existence. Stewardesses for Women's Rights folded in the spring of 1976.

Steinem, who grew up reading Wonder Woman comics, was also a key player in the restoration of Wonder Woman's powers and traditional costume, which were restored in issue #204 (January–February 1973). Steinem, offended that the most famous female superhero had been depowered, had placed Wonder Woman (in costume) on the cover of the first issue of Ms. (1972) – Warner Communications, DC Comics' owner, was an investor – which also contained an appreciative essay about the character.

In 1976, the first women-only Passover seder was held in Esther M. Broner's New York City apartment and led by Broner, with 13 women attending, including Steinem.

In 1977, Steinem became an associate of the Women's Institute for Freedom of the Press (WIFP). WIFP is an American nonprofit publishing organization. The organization works to increase communication between women and connect the public with forms of women-based media.

In 1984 Steinem was arrested along with a number of members of Congress and civil rights activists for disorderly conduct outside the South African embassy while protesting against the South African apartheid system.

At the outset of the Gulf War in 1991, Steinem, along with prominent feminists Robin Morgan and Kate Millett, publicly opposed an incursion into the Middle East and asserted that ostensible goal of "defending democracy" was a pretense.

During the Clarence Thomas sexual harassment scandal in 1991, Steinem voiced strong support for Anita Hill and suggested that one day Hill herself would sit on the Supreme Court.

In 1992, Steinem co-founded Choice USA, a non-profit organization that mobilizes and provides ongoing support to a younger generation that lobbies for reproductive choice.

In 1993 Steinem co-produced and narrated an Emmy Award-winning TV documentary for HBO about child abuse, called, "Multiple Personalities: The Search for Deadly Memories." Also in 1993, she and Rosilyn Heller co-produced an original TV movie for Lifetime, "Better Off Dead," which examined the parallel forces that both oppose abortion and support the death penalty.

She contributed the piece "The Media and the Movement: A User's Guide" to the 2003 anthology Sisterhood Is Forever: The Women's Anthology for a New Millennium, edited by Robin Morgan.

On June 1, 2013, Steinem performed on stage at the "Chime For Change: The Sound Of Change Live" Concert at Twickenham Stadium in London, England. Later in 2014, UN Women began its commemoration of the 20th anniversary of the Fourth World Conference on Women, and as part of that campaign Steinem (and others) spoke at the Apollo Theater in New York City. Chime For Change was funded by Gucci, focusing on using innovative approaches to raise funds and awareness especially regarding girls and women.

Steinem has stated, "I think the fact that I've become a symbol for the women's movement is somewhat accidental. A woman member of Congress, for example, might be identified as a member of Congress; it doesn't mean she's any less of a feminist but she's identified by her nearest male analog. Well, I don't have a male analog so the press has to identify me with the movement. I suppose I could be referred to as a journalist, but because Ms. is part of a movement and not just a typical magazine, I'm more likely to be identified with the movement. There's no other slot to put me in."

Contrary to popular belief, Steinem did not coin the feminist slogan "A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle." Although she helped popularize it, the phrase is actually attributable to Irina Dunn. When Time magazine published an article attributing the saying to Steinem, Steinem wrote a letter saying the phrase had been coined by Dunn.

Another phrase sometimes wrongly attributed to Steinem is, "If men could get pregnant, abortion would be a sacrament." Steinem herself attributed it to "an old Irish woman taxi driver in Boston," whom she said she and Florynce Kennedy met.

As for 2015, she joined the thirty leading international women peacemakers and became an honorary co-chairwoman of 2015 Women's Walk For Peace In Korea with Mairead Maguire. The group's main goal is to advocate disarmament and seek Korea's reunification. It will be holding international peace symposiums both in Pyongyang and Seoul in which women from both North Korea and South Korea can share experiences and ideas of mobilizing women to stop the Korean crisis. The group's specific hope is to walk across the 2-mile wide Korean Demilitarized Zone that separates North Korea and South Korea which is meant to be a symbolic action taken for peace in the Korean peninsular suffering for 70 years after its division at the end of World War II. It is especially believed that the role of women in this act would help and support the reunification of family members divided by the split prolonged for 70 years.

Steinem is currently an honorary co-chair of the Democratic Socialists of America.

Involvement in political campaigns

Steinem's involvement in presidential campaigns stretches back to her support of Adlai Stevenson in the 1952 presidential campaign.

1968 election

A proponent of civil rights and fierce critic of the Vietnam War, Steinem was initially drawn to Senator Eugene McCarthy because of his "admirable record" on those issues, but in meeting him and hearing him speak, she found him "cautious, uninspired, and dry." As the campaign progressed, Steinem became baffled at "personally vicious" attacks that McCarthy leveled against his primary opponent Robert Kennedy, even as "his real opponent, Hubert Humphrey, went free."

On a late-night radio show, Steinem garnered attention for declaring, "George McGovern is the real Eugene McCarthy." In 1968, Steinem was chosen to pitch the arguments to McGovern as to why he should enter the presidential race that year; he agreed, and Steinem "consecutively or simultaneously served as pamphlet writer, advance 'man', fund raiser, lobbyist of delegates, errand runner, and press secretary."

McGovern lost the nomination at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, and Steinem later wrote of her astonishment at Hubert Humphrey's "refusal even to suggest to Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley that he control the rampaging police and the bloodshed in the streets."

1972 election

Steinem was reluctant to re-join the McGovern campaign, as although she had brought in McGovern's single largest campaign contributor in 1968, she "still had been treated like a frivolous pariah by much of McGovern's campaign staff." In April 1972, Steinem remarked that he "still doesn't understand the Women's Movement".

McGovern ultimately excised the abortion issue from the party's platform, and recent publications show McGovern was deeply conflicted on the issue. Steinem later wrote this description of the events:

The consensus of the meeting of women delegates held by the caucus had been to fight for the minority plank on reproductive freedom; indeed our vote had supported the plank nine to one. So fight we did, with three women delegates speaking eloquently in its favor as a constitutional right. One male Right-to-Life zealot spoke against, and Shirley MacLaine also was an opposition speaker, on the grounds that this was a fundamental right but didn't belong in the platform. We made a good showing. Clearly we would have won if McGovern's forces had left their delegates uninstructed and thus able to vote their consciences.

However, Germaine Greer flatly contradicted Steinem's account, reporting, "Jacqui Ceballos called from the crowd to demand abortion rights on the Democratic platform, but Bella and Gloria stared glassily out into the room," thus killing the abortion rights platform," and asking "Why had Bella and Gloria not helped Jacqui to nail him on abortion? What reticence, what loserism had afflicted them?" Steinem later recalled that the 1972 Convention was the only time Greer and Steinem ever met.

The cover of Harper's that month read, "Womanlike, they did not want to get tough with their man, and so, womanlike, they got screwed."

2004 election

In the run-up to the 2004 election, Steinem voiced fierce criticism of the Bush administration, asserting, "There has never been an administration that has been more hostile to women's equality, to reproductive freedom as a fundamental human right, and has acted on that hostility," adding, "If he is elected in 2004, abortion will be criminalized in this country." At a Planned Parenthood event in Boston, Steinem declared Bush "a danger to health and safety," citing his antagonism to the Clean Water Act, reproductive freedom, sex education, and AIDS relief.

2008 election

Steinem was an active participant in the 2008 presidential campaign, and praised both the Democratic front-runners, commenting,

Both Senators Clinton and Obama are civil rights advocates, feminists, environmentalists, and critics of the war in Iraq ... Both have resisted pandering to the right, something that sets them apart from any Republican candidate, including John McCain. Both have Washington and foreign policy experience; George W. Bush did not when he first ran for president.

Nevertheless, Steinem endorsed Senator Hillary Clinton, citing her broader experience, and saying that the nation was in such bad shape it might require two terms of Clinton and two of Obama to fix it.

She also made headlines for a New York Times op-ed in which she cited gender and not race as "probably the most restricting force in American life". She elaborated, "Black men were given the vote a half-century before women of any race were allowed to mark a ballot, and generally have ascended to positions of power, from the military to the boardroom, before any women." This was attacked, however, from critics saying that white women were given the vote unabridged in 1920, whereas many blacks, female or male, could not vote until the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and some were lynched for trying, and that many white women advanced in the business and political worlds before black women and men.

Steinem again drew attention for, according to the New York Observer, seeming "to denigrate the importance of John McCain's time as a prisoner of war in Vietnam"; Steinem's broader argument "was that the media and the political world are too admiring of militarism in all its guises."

Following McCain's selection of Sarah Palin as his running mate, Steinem penned an op-ed in which she labeled Palin an "unqualified woman" who "opposes everything most other women want and need," described her nomination speech as "divisive and deceptive", called for a more inclusive Republican Party, and concluded that Palin resembled "Phyllis Schlafly, only younger."

2016 election

In an HBO interview with Bill Maher, Steinem, when asked to explain the broad support for Bernie Sanders among young Democratic women, responded, "When you're young, you're thinking, 'Where are the boys? The boys are with Bernie.'" Her comments triggered widespread criticism, and Steinem later issued an apology and said her comments had been "misinterpreted".

Steinem was an honorary co-chair of and speaker at the Women's March on Washington on January 21, 2017, the day after the inauguration of Donald Trump as President.

CIA ties

In May 1975, Redstockings, a radical feminist group, published a report that Steinem and others put together on the Vienna Youth Festival and its attendees for the Independent Research Service. Though she acknowledged having worked for the CIA-financed foundation in the late 1950s and early 1960s in interviews given to the New York Times and Washington Post in 1967 in the wake of the Ramparts magazine CIA exposures (nearly two years before Steinem attended her first Redstockings or feminist meeting), Steinem in 1975 denied any continuing involvement.

In her book "My Life On The Road", Steinem spoke openly about the relationship she had with "The Agency" in the 1950s and 1960s. While popularly pilloried because of her paymaster, Steinem defended the CIA relationship, saying: "In my experience The Agency was completely different from its image; it was liberal, nonviolent and honorable."

Personal life

Steinem was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1986 and trigeminal neuralgia in 1994.

On September 3, 2000, at age 66, Steinem married David Bale, father of actor Christian Bale. The wedding was performed at the home of her friend Wilma Mankiller, the first female Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation. Steinem and Bale were married for only three years before he died of brain lymphoma on December 30, 2003, at age 62.

Previously, she had had a four-year relationship with the publisher Mortimer Zuckerman.

Commenting on aging, Steinem says that as she approached 60 she felt like she entered a new phase in life that was free of the "demands of gender" that she faced from adolescence onward.

Political positions

Although most frequently considered a liberal feminist, Steinem has repeatedly characterized herself as a radical feminist. More importantly, she has repudiated categorization within feminism as "nonconstructive to specific problems," saying: "I've turned up in every category. So it makes it harder for me to take the divisions with great seriousness." Nevertheless, on concrete issues, Steinem has staked several firm positions.

Female genital mutilation and male circumcision

In 1979, Steinem wrote the article on female genital mutilation that brought it into the American public's consciousness; the article, "The International Crime of Female Genital Mutilation," was published in the March 1979 issue of Ms.. The article reported on the "75 million women suffering with the results of genital mutilation." According to Steinem, "The real reasons for genital mutilation can only be understood in the context of the patriarchy: men must control women's bodies as the means of production, and thus repress the independent power of women's sexuality." Steinem's article contains the basic arguments that would later be developed by philosopher Martha Nussbaum.

On male circumcision, she commented, "These patriarchal controls limit men's sexuality too ... That's why men are asked symbolically to submit the sexual part of themselves and their sons to patriarchal authority, which seems to be the origin of male circumcision, a practice that, even as advocates admit, is medically unnecessary 90% of the time. Speaking for myself, I stand with many brothers in eliminating that practice too."

Feminist theory

Steinem has frequently voiced her disapproval of the obscurantism and abstractions some claim to be prevalent in feminist academic theorizing. She said, "Nobody cares about feminist academic writing. That's careerism. These poor women in academia have to talk this silly language that nobody can understand in order to be accepted ... But I recognize the fact that we have this ridiculous system of tenure, that the whole thrust of academia is one that values education, in my opinion, in inverse ratio to its usefulness—and what you write in inverse relationship to its understandability." Steinem later singled out deconstructionists like Judith Butler for criticism, saying, "I always wanted to put a sign up on the road to Yale saying, 'Beware: Deconstruction Ahead'. Academics are forced to write in language no one can understand so that they get tenure. They have to say 'discourse', not 'talk'. Knowledge that is not accessible is not helpful. It becomes aeralised."

Pornography

Steinem has criticized pornography, which she distinguishes from erotica, writing: "Erotica is as different from pornography as love is from rape, as dignity is from humiliation, as partnership is from slavery, as pleasure is from pain." Steinem's argument hinges on the distinction between reciprocity versus domination, as she writes, "Blatant or subtle, pornography involves no equal power or mutuality. In fact, much of the tension and drama comes from the clear idea that one person is dominating the other."

On the issue of same-sex pornography, Steinem asserts, "Whatever the gender of the participants, all pornography including male-male gay pornography is an imitation of the male-female, conqueror-victim paradigm, and almost all of it actually portrays or implies enslaved women and master." Steinem has also cited "snuff films" as a serious threat to women.

Same-sex marriage

In an essay published in Time magazine on August 31, 1970, "What Would It Be Like If Women Win," Steinem wrote about same-sex marriage in the context of the "Utopian" future she envisioned, writing:

What will exist is a variety of alternative life-styles. Since the population explosion dictates that childbearing be kept to a minimum, parents-and-children will be only one of many "families": couples, age groups, working groups, mixed communes, blood-related clans, class groups, creative groups. Single women will have the right to stay single without ridicule, without the attitudes now betrayed by "spinster" and "bachelor." Lesbians or homosexuals will no longer be denied legally binding marriages, complete with mutual-support agreements and inheritance rights. Paradoxically, the number of homosexuals may get smaller. With fewer over-possessive mothers and fewer fathers who hold up an impossibly cruel or perfectionist idea of manhood, boys will be less likely to be denied or reject their identity as males.

Although Steinem did not mention or advocate same-sex marriage in any published works or interviews for more than three decades, she again expressed support for same-sex marriage in the early 2000s, stating in 2004 that " idea that sexuality is only okay if it ends in reproduction oppresses women—whose health depends on separating sexuality from reproduction—as well as gay men and lesbians." Steinem is also a signatory of the 2008 manifesto, "Beyond Same-Sex Marriage: A New Strategic Vision For All Our Families and Relationships", which advocates extending legal rights and privileges to a wide range of relationships, households, and families.

Transgender rights

In 1977, Steinem expressed disapproval that the heavily publicized sex reassignment surgery of tennis player Renée Richards had been characterized as "a frightening instance of what feminism could lead to" or as "living proof that feminism isn't necessary." Steinem wrote, "At a minimum, it was a diversion from the widespread problems of sexual inequality." She also wrote that, while she supported the right of individuals to identify as they choose, she claimed that, in many cases, transsexuals "surgically mutilate their own bodies" in order to conform to a gender role that is inexorably tied to physical body parts. She concluded that "feminists are right to feel uncomfortable about the need for and uses of transsexualism." The article concluded with what became one of Steinem's most famous quotes: "If the shoe doesn't fit, must we change the foot?" Although clearly meant in the context of transsexuality, the quote is frequently mistaken as a general statement about feminism.

On October 2, 2013, Steinem clarified her remarks on transgender people in an op-ed for The Advocate, writing that critics failed to consider that her 1977 essay was "written in the context of global protests against routine surgical assaults, called female genital mutilation by some survivors." Steinem later in the piece expressed unequivocal support for transgender people, saying that transgender people "including those who have transitioned, are living out real, authentic lives. Those lives should be celebrated, not questioned." She also apologized for any pain her words might have caused.

Awards and honors

- American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California's Bill of Rights Award

- American Humanist Association's 2012 Humanist of the Year (2012)

- Biography magazine's 25 most influential women in America (Steinem was listed as one of them)

- Clarion award

- DVF Lifetime Leadership Award (2014)

- Emmy Citation for excellence in television writing

- Esquire magazine's 75 greatest women of all time (Steinem was listed as one of them) (2010)

- Equality Now's international human rights award, given jointly to her and Efua Dorkenoo (2000)

- Front Page award

- Glamour magazine's "The 75 Most Important Women of the Past 75 Years" (Steinem was listed as one of them) (2014)

- Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund's Liberty Award

- Library Lion award (2015)

- The Ms. Foundation for Women's Gloria Awards, given annually since 1988, are named after Steinem.

- National Gay Rights Advocates Award

- National Magazine awards

- National Women's Hall of Fame inductee (1993)

- New York Women's Foundation's Century Award (2014)

- Parenting magazine's Lifetime Achievement Award (1995)

- Penney-Missouri Journalism Award

- Presidential Medal of Freedom (2013)

- Rutgers University announced the Gloria Steinem Endowed Chair in September 2014. The Chair will fund teaching and research for someone (not necessarily a woman) who exemplifies Steinem's values of equal representation in the media. This person will teach at least one undergraduate course per semester.

- Sara Curry Humanitarian Award (2007)

- Simmons College's Doctorate of Human Justice

- Society of Professional Journalists' Lifetime Achievement in Journalism Award

- Supersisters trading card set (card number 32 featured Steinem's name and picture) (1979)

- United Nations' Ceres Medal

- United Nations' Society of Writers Award

- University of Missouri School of Journalism Award for Distinguished Service in Journalism

- Women's Sports Journalism Award

- 2015 Richard C. Holbrooke Distinguished Achievement Award of the Dayton Literary Peace Prize

- Recipient of the 2017 Ban Ki-moon Award For Women's Empowerment

In media

In 1995, Education of a Woman: The Life of Gloria Steinem, by Carolyn Heilbrun, was published.

In 1997, Gloria Steinem: Her Passions, Politics, and Mystique, by Sydney Ladensohn Stern, was published.

In the musical Legally Blonde, which premiered in 2007, Steinem is mentioned in the scene where Elle Woods wears a flashy Bunny costume to a party, and must pretend to be dressed as Gloria Steinem "researching her feminist manifesto 'I Was A Playboy Bunny'." (The actual name of the piece by Steinem being referred to here is "A Bunny's Tale".)

In 2011, Gloria: In Her Own Words, a documentary, first aired.

In 2013, Female Force: Gloria Steinem, a comic book by Melissa Seymour, was published.

Also in 2013, Steinem was featured in the documentary MAKERS: Women Who Make America about the feminist movement.

In 2014, Who Is Gloria Steinem?, by Sarah Fabiny, was published.

Also in 2014, Steinem appeared in season 1, episode 8, of the television show The Sixties.

Also in 2014, Steinem appeared in season 6, episode 3, of the television show The Good Wife.

In 2016, Steinem was featured in the catalog of clothing retailer Lands' End. After an outcry from anti-abortion customers, the company removed Steinem from their website, stating on their Facebook page: "It was never our intention to raise a divisive political or religious issue, so when some of our customers saw the recent promotion that way, we heard them. We sincerely apologize for any offense." The company then faced further criticism online, this time both from customers who were still unhappy that Steinem had been featured in the first place, and customers who were unhappy that Steinem had been removed.

In Jennifer Lopez's 2016 music video for her song "Ain't Your Mama", Steinem can be heard saying part of her "Address to the Women of America" speech, specifically, "This is no simple reform. It really is a revolution."

Also in 2016, the television series Woman premiered, featuring Steinem as producer and host; it is a documentary series concerning sexist injustice and violence worldwide.

The Gloria Steinem Papers are held in the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College, under collection number MS 237.

Works

- The Thousand Indias (1957)

- The Beach Book (1963), New York: Viking Press. OCLC 1393887

- Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions (1983), New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. ISBN 978-0-03-063236-5

- Marilyn: Norma Jean (1986), with George Barris, New York: Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-0060-3

- Revolution from Within (1992), Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-81240-5

- Moving beyond Words (1993), New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-64972-2

- Doing Sixty & Seventy (2006), San Francisco: Elders Academy Press. ISBN 978-0-9758744-2-4

- My Life on the Road (2015), New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-45620-9

See also

References

- ^ "Gloria Steinem Fast Facts". CNN. September 6, 2014. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Gloria Steinem". Encyclopedia of World Biography. 2004. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Board of Directors". Women's Media Center. Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Feminist Dad of the Day: Christian Bale". Women and Hollywood. July 25, 2012. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Denes, Melissa (January 16, 2005). "'Feminism? It's hardly begun'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved December 31, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Official Website of Author and Activist Gloria Steinem – About". Gloriasteinem.com. Archived from the original on March 27, 2018. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- ^ "Gloria Steinem". historynet.com. Archived from the original on October 4, 2014. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Steinem, Gloria (April 7, 1969). "Gloria Steinem, After Black Power, Women's Liberation". New York Magazine. Archived from the original on January 1, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Gloria Steinem, Feminist Pioneer, Leader for Women's Rights and Equality". The Connecticut Forum. Archived from the original on July 15, 2015. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "The Invisible Majority – Women & the Media". Feminist.com. Archived from the original on October 29, 2014. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Education of a Woman: The Life of Gloria Steinem – Carolyn G. Heilbrun – Google Books". Books.google.ca. July 20, 2011. Archived from the original on January 29, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Finding Your Roots, February 23, 2016, PBS.

- "Gloria Steinem". Jewish Women's Archive. Archived from the original on June 7, 2014. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Ancestry of Gloria Steinem". Wargs.com. Archived from the original on March 11, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Gloria Steinem's Interactive Family Tree | Finding Your Roots". PBS. February 25, 2016. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Pogrebin, Letty Cottin (March 20, 2009). "Gloria Steinem". Jewish Women's Archive. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Steinem, Gloria (1983). Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. pp. 140–142. ISBN 978-0-03-063236-5.

- Marcello, Patricia. Gloria Steinem: A Biography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004. p. 20.

- ^ Marcello, Patricia. Gloria Steinem: A Biography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004.

- ^ Steinem, Gloria (1984). Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions (1 ed.). New York: Henry Holt & Co.

- "Classmates remember Steinem's Toledo days". Toledo Free Press. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Gloria Steinem class of 1952". Western High School. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ^ "Gloria Steinem". Biography.com. Archived from the original on October 4, 2011. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Bird, Kai (1992). The Chairman: John J. McCloy, the making of the American establishment. Simon & Schuster. pp. 483–484.

- ^ "C.I.A. Subsidized Festival Trips; Hundreds of Students Were Sent to World Gatherings". The New York Times. February 21, 1967. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Cooke, Jon. "Wrightson's Warren Days". TwoMorrows. Archived from the original on January 27, 2010. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mclellan, Dennis (July 2, 2008). "Clay Felker, 82; editor of New York magazine led New Journalism charge". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 30, 2008. Retrieved November 23, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Fox, Margalit (February 5, 2006). "Betty Friedan, Who Ignited Cause in 'Feminine Mystique,' Dies at 85". Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Kolhatkar, Sheelah (December 18, 2005). "Gloria Steinem". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on November 20, 2009. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Steinem, Gloria (May 1963). "A Bunny's Tale" (PDF). Show. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 18, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Steinem, Gloria (1995). "I Was a Playboy Bunny" (PDF). Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 27, 2011. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- "Interview With Gloria Steinem". ABC News. 2011. Archived from the original on June 2, 2015. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "For feminist Gloria Steinem, the fight continues (interview)". Minnesota Public Radio. June 15, 2009. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Elizabeth Thomson; David Gutman (1987). The Lennon Companion: Twenty-Five Years of Comment. Da Capo Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-306-81270-5. Archived from the original on September 30, 2015.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Patricia Cronin Marcello (2004). Gloria Steinem: A Biography. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-313-32576-2. Archived from the original on September 8, 2013. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Steinem, Gloria (April 6, 1998). "30th Anniversary Issue / Gloria Steinem: First Feminist". Nymag.com. Archived from the original on March 11, 2013. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Pogrebin, Abigail (October 30, 2011). "An Oral History of 'Ms.' Magazine". Nymag.com. Archived from the original on July 9, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rachel Cooke (November 13, 2011). "Gloria Steinem: 'I think we need to get much angrier'". London: Guardian. Archived from the original on October 1, 2013. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Gilbert, Lynn & Moore, Gaylen, "Particular Passions: Talks With Women Who Shaped Our Times". Clarkson Potter, 1981. p. 166.

- "The Eighties, Gloria Steinem". Colored Reflections. Archived from the original on February 1, 2016. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ms. Magazine History". Msmagazine.com. December 31, 2001. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Ruth, Tam (December 31, 2001). "Gloria Steinem: No such thing as a 'feminist icon'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Steinem, Gloria (October 1978). "If Men Could Menstruate". Ms.

- Steinem, Gloria (March 22, 1998). "feminists and the Clinton Question". New York Times; cited on message board. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Suleiman, Daniel (March 3, 1998). "The Whore Principle". Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on December 12, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Frago, William (March 25, 1998). "Are Feminists Right to Stand by Clinton?; Enabling Bad Behavior". Harvard Crimson. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest" January 30, 1968 New York Post.

- Steinem, Gloria (April 4, 1969). "After Black Power, Women's Liberation". New York. Archived from the original on July 1, 2010. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Gary Donaldson (2007). Modern America: A Documentary History of the Nation Since 1945. M.E. Sharpe. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-7656-1537-4. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "TESTIMONY BEFORE SENATE HEARINGS ON THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT". Voicesofdemocracy.umd.edu. May 6, 1970. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Steinem, Gloria (August 31, 1970). "What It Would Be Like If Women Win". Time Magazine. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Jodi O'Brien (November 26, 2008). Encyclopedia of Gender and Society. SAGE Publications. pp. 652–. ISBN 978-1-4522-6602-2. Archived from the original on March 18, 2015. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Johnson Lewis, Jone. "Gloria Steinem Quotes". About. Archived from the original on July 12, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Freeman, Jo (February 2005). "Shirley Chisholm's 1972 Presidential Campaign". University of Illinois at Chicago Women's History Project. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- ^ "Guide to the Records of Stewardesses for Women's Rights WAG 061". Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Archives. Archived from the original on July 2, 2011. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ McAvennie, Michael; Dolan, Hannah, ed. (2010). "1970s". DC Comics Year By Year A Visual Chronicle. Dorling Kindersley. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-7566-6742-9.

After nearly five years of Diana Prince's non-powered super-heroics, writer-editor Robert Kanigher and artist Don Heck restored Wonder Woman's ... well, wonder.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Greenberger, Robert (2010). Wonder Woman: Amazon. Hero. Icon. Rizzoli Universe Promotional Books. p. 175. ISBN 0-7893-2416-4.

Journalist and feminist Gloria Steinem ... was tapped in 1970 to write the introduction to Wonder Woman, a hardcover collection of older stories. Steinem later went on to edit Ms., with the first issue published in 1972, featuring the Amazon Princess on its cover. In both publications, the heroine's powerless condition during the 1970s was pilloried. A feminist backlash began to grow, demanding that Wonder Woman regain the powers and costume that put her on a par with the Man of Steel.

- This Week in History – E.M. Broner publishes "The Telling" | Jewish Women's Archive Archived April 14, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Jwa.org (March 1, 1993). Retrieved on October 18, 2011.

- "Associates | The Women's Institute for Freedom of the Press". www.wifp.org. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Arrested at embassy". Gadsden Times. December 20, 1984. p. A10. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- Steinem, Gloria (January 20, 1991). "We Learned the Wrong Lessons in Vietnam; A Feminist Issue Still". New York Times. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Sontag, Deborah (April 26, 1992). "Anita Hill and Revitalizing Feminism". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Choice USA". Choice USA. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Sheaffer, Robert (April 1997). "Feminism, the Noble Lie". Free Inquiry Magazine. Archived from the original on November 2, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Grenier, Richard (July 25, 1994). "Feminists falsify facts for effect – controversy over Gloria Steinem's use of anorexia death statistics stirs controversy over exaggeration for political effect". Insight on the News. Archived from the original on November 21, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Library Resource Finder: Table of Contents for: Sisterhood is forever : the women's anth". Vufind.carli.illinois.edu. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Gloria Steinem Pictures – Show At "Chime For Change: The Sound Of Change Live" Concert". Zimbio. May 31, 2013. Archived from the original on March 17, 2015. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Gloria Steinem Helps UN Women Unveil Beijing+20 Campaign". Zimbio. July 1, 2014. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Chime for Change". www.chimeforchange.org. Archived from the original on January 28, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Gilbert, Lynn (December 10, 2012). Particular Passions: Gloria Steinem. Women of Wisdom Series (1st ed.). New York, NY: Lynn Gilbert Inc. ISBN 978-1-61979-354-5. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- "A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle". The Phrase Finder. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Letters, Time magazine, US edition, September 16, 2000, and Australian edition, October 9, 2000. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- Bardi, Jennifer (August 14, 2012). "The Humanist Interview with Gloria Steinem". Thehumanist.org. Archived from the original on December 12, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Gladstone, Rick (March 11, 2015). "With Plan to Walk Across DMZ, Women Aim for Peace in Korea". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 9, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- "North Korea Has Given A Gloria Steinem-Led Peace March The Thumbs Up". Archived from the original on February 23, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Women Cross DMZ – Ending The Korean War, Reuniting Families". www.womencrossdmz.org. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Nations, Associated Press at the United (April 3, 2015). "North Korea supports Gloria Steinem-led women's walk across the DMZ". Archived from the original on December 31, 2016 – via The Guardian.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Our Structure, Democratic Socialists of America, archived from the original on March 15, 2017, retrieved March 9, 2017

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Lazo, Caroine. Gloria Steinem: Feminist Extraordinaire. New York: Lerner Publications, 1998. p. 28.

- Miroff, Bruce. The Liberals' Moment: The McGovern Insurgency and the Identity Crisis of the Democratic Party. University Press of Kansas, 2007. p. 206.

- Miroff. p. 207.

- Harper's Magazine October 1972.

- Evans, Joni (April 16, 2009). "Gloria Steinem: Still Committing 'Outrageous Acts' at 75". Wow. Archived from the original on January 14, 2011. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Harper's Magazine Archives". Harpers.org. Archived from the original on August 6, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Buzzflash Interview". Buzzflash.com. February 5, 2004. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Feminist Pioneer Gloria Steinem: "Bush is a Danger to Our Health and Safety"". Democracynow.org. July 26, 2004. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Steinem, Gloria (February 7, 2007). "Right Candidates, Wrong Question". New York Times. Archived from the original on January 29, 2017. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Feldman, Claudia (September 18, 2007). "Has Gloria Steinem mellowed? No way". The Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 21, 2008. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Steinem, Gloria (January 8, 2008). "Women Are Never Front-Runners". New York Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2014. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Gharib, Ali (January 16, 2008). "Democratic Race Sheds Issues for Identities". Inter Press News. Archived from the original on October 10, 2016. Retrieved March 16, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Stanage, Niall (March 8, 2008). "Stumping for Clinton, Steinem Says McCain's POW Cred Is Overrated". New York Observer. Archived from the original on August 30, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Steinem, Gloria (September 4, 2008). "Palin: wrong woman, wrong message". LA Times. Archived from the original on April 17, 2010. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Rappeport, Alan (February 7, 2016). "Gloria Steinem and Madeleine Albright Scold Young Women Backing Bernie Sanders". New York Times. Archived from the original on February 7, 2016. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Contrera, Jessica (February 7, 2016). "Gloria Steinem is apologizing for insulting female Bernie Sanders supporters". Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 8, 2016. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Gloria Steinem and the CIA". NameBase. The New York Times. February 21, 1967. Archived from the original on August 30, 2010. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Gloria Steinem Spies on Students for the CIA". NameBase. Redstockings. 1975. Archived from the original on September 3, 2012. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Harrington, Stephanie (July 4, 1976). "It Changed My Life". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 10, 2009. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Kounalakis, Marko s (October 25, 2015). "The feminist was a spook". Chicago Tribune.

- Holt, Patricia (September 22, 1995). "Making Ms.Story / The biography of Gloria Steinem, a woman of controversy and contradictions". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gorney, Cynthia (November–December 1995). "Gloria". Mother Jones. Archived from the original on July 29, 2016. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Feminist icon Gloria Steinem first-time bride at 66". CNN.com. September 5, 2000. Archived from the original on September 17, 2007. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

- von Zeilbauer, Paul (January 1, 2004). "David Bale, 62, Activist and businessman". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Melissa Denes. "'Feminism? It's hardly begun' | World news". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Steinem, Gloria (October 26, 2015). "At 81, Feminist Gloria Steinem Finds Herself Free Of The 'Demands Of Gender'". NPR. Archived from the original on November 4, 2015. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Marianne Schnall Interview". Feminist.com. April 3, 1995. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The International Crime of Female Genital Mutilation," by Gloria Steinem. Ms., March 1979, p. 65.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. Sex & Social Justice. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. pp. 118–129.

- "What have FGC opponents said publicly about male genital cutting?". Noharmm.org. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Denes, Melissa (January 17, 2005). "'Feminism? It's hardly begun'". London: The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Erotica and Pornography: A Clear and Present Difference. Ms. November 1978, p. 53. & Pornography—Not Sex but the Obscene Use of Power. Ms. August 1977, p. 43. Both retrieved November 16, 2014.

- "What Would It Be Like If Women Win". Associated Press. August 31, 1970. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Steptoe, Sonja; Steinem, Gloria (March 28, 2004). "10 Questions For Gloria Steinem". Time Magazine. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Signatories". BeyondMarriage.org. Archived from the original on April 20, 2008. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ Steinem, Gloria (October 2, 2013). "Op-ed: On Working Together Over Time". Advocate.com. Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "The Lifetime Leadership Award, Gloria Steinem". www.dvf.com. 2014. Archived from the original on November 8, 2014. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "The 75 Greatest Women of All Time". Esquire Magazine. May 2010. Archived from the original on November 13, 2014. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Read a Peace Report- Remembering our friend and colleague, Efua Dorkenoo". Equality Now. October 28, 2014. Archived from the original on November 2, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Glamour Magazine. "The Most Inspiring Female Celebrities, Entrepreneurs, and Political Figures: Glamour.com". Glamour. Archived from the original on December 20, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Katie Van Syckle. "Gloria Steinem: Hillary Will Have a Hard Time – The Cut". Nymag.com. Archived from the original on November 6, 2015. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Sophie Rosenblum (May 24, 2010). "Women Celebrated and Supported at the 22nd Annual Gloria Awards". NoVo Foundation. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Marianne Garvey, Brian Niemietz with Molly Friedman (May 11, 2014). "Denzel Washington dining out at SoHo hotspot causes a spicy fray". NY Daily News. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- "Obama Awards Medal of Freedom to 16 Americans". Voanews.com. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Wilson, Teddy. "'If We Each Have a Torch, There's a Lot More Light': Gloria Steinem Accepts the Presidential Medal of Freedom". Rhrealitycheck.org. Archived from the original on March 31, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Women's Media Center Congratulates Co-Founder Gloria Steinem on Presidential Medal of Freedom | Women's Media Center". Womensmediacenter.com. August 8, 2013. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Zernike, Kate (September 26, 2014). "Rutgers to Endow Chair Named for Gloria Steinem". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 29, 2014. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lin Lan (September 29, 2014). "Rutgers endows chair for feminist icon Gloria Steinem". The Daily Targum. Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Congressional Record Volume 153, Number 18". U.S. Congress. January 30, 2007. Archived from the original on April 21, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Wulf, Steve (March 23, 2015). "Supersisters: Original Roster". Espn.go.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Gloria Steinem, 2015 Recipient of the Richard C. Holbrooke Distinguished Achievement Award". Dayton Literary Peace Prize. November 10, 2012. Archived from the original on August 10, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Dayani, Dilshad. "Ban Ki-moon and Women in Power Define Empowerment With Their Renewed Pledge to "Help A Woman Rise."" Thrive Global, October 18, 2017. https://www.thriveglobal.com/stories/35630-how-youtube-can-be-your-business-lifeline

- Bridget Berry. "Gloria Steinem". Wagner College. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Bryan-Paul Frost; Jeffrey Sikkenga (January 1, 2003). History of American Political Thought. Lexington Books. pp. 711–. ISBN 978-0-7391-0624-2. Archived from the original on March 18, 2015.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - McNamara, Mary (August 15, 2011). "Television review: 'Gloria: In Her Own Words'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 23, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Bahadur, Nina (September 9, 2013). "Gloria Steinem 'Female Force' Comic Book Looks Seriously Amazing". Huffingtonpost.com. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Romy Zipken (September 10, 2013). "Gloria Steinem Is A Comic Book Star". jewcy.com. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Gloria Steinem Comic Book Joins a Strong 'Female Force' Not to be Reckoned With | VITAMIN W". Vitaminw.co. September 11, 2013. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Radish, Christina (2013). "Gloria Steinem Talks PBS Documentary MAKERS: WOMEN WHO MAKE AMERICA, the Current State of Women's Rights, Today's Most Inspiring Women, & More". collider.com. Archived from the original on April 22, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Sarah Fabiny; Max Hergenrother; Nancy Harrison (December 26, 2014). Who Is Gloria Steinem?. Penguin Group US. ISBN 978-0-698-18737-5. Archived from the original on March 18, 2015.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "The Sixties – Season 1, Episode 8: The Times They Are-a-Changin', aired 7/24/2014". tv.com. 2014. Archived from the original on August 8, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "The Good Wife: Good Law? - Season 6, Episode 3". Celebrity Justice. Archived from the original on November 23, 2014. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "'Catalog Interview With Gloria Steinem Has Lands' End on Its Heels'". New York Times. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - JenniferLopezVEVO (May 6, 2016). "Jennifer Lopez – Ain't Your Mama". Archived from the original on January 29, 2018 – via YouTube.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Recording of an excerpt of the Address to the Women of America at MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on October 31, 2009.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Gloria Steinem talks about 'Woman'". Bendbulletin.com. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Gloria Steinem Papers, 1940–2000 [ongoing], 237 boxes (105.75 linear ft.), Collection number: MS 237". Sophia Smith Collection. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

Further reading

- Education of A Woman: The Life of Gloria Steinem by Carolyn Heilbrun (Ballantine Books, United States, 1995) ISBN 978-0-345-40621-7

- Gloria Steinem: Her Passions, Politics, and Mystique by Sydney Ladensohn Stern (Birch Lane Press, 1997) ISBN 978-1-55972-409-8

External links

Library resources aboutGloria Steinem

By Gloria Steinem

- Official website

Quotations related to Gloria Steinem at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Gloria Steinem at Wikiquote Media related to Gloria Steinem at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gloria Steinem at Wikimedia Commons- Profile at Feminist.com

- Template:Worldcat id

- Gloria Steinem Video produced by Makers: Women Who Make America (affiliated with Women Make Movies)

- Gloria Steinem Papers at the Sophia Smith Collection

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Michals, Debra "Gloria Steinem". National Women's History Museum. 2017.

| Inductees to the National Women's Hall of Fame | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Feminism | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History |

| ||||||

| Movements and ideologies |

| ||||||

| Concepts |

| ||||||

| Theory |

| ||||||

| By country |

| ||||||

| Lists |

| ||||||

- 1934 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American women writers

- 21st-century American journalists

- 21st-century American women writers

- Activists against female genital mutilation

- Activists from Ohio

- American feminist writers

- American humanists

- American people of German descent

- American people of German-Jewish descent

- American people of Polish-Jewish descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- American political activists

- American political writers

- American pro-choice activists

- American socialists

- American tax resisters

- American women activists

- American women journalists

- American women's rights activists

- Anti-pornography activists

- Anti-pornography feminists

- Breast cancer survivors

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- Critics of postmodernism

- Feminist theorists

- Feminist writers

- Jewish American journalists

- Jewish American writers

- Jewish feminists

- Jewish humanists

- Jewish socialists

- Journalists from Ohio

- LGBT rights activists from the United States

- Members of the Democratic Socialists of America

- Opinion journalists

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Radical feminists

- Smith College alumni

- Socialist feminists

- Writers from Toledo, Ohio

- Missouri Lifestyle Journalism Award winners